Introduction: The Line of Fire

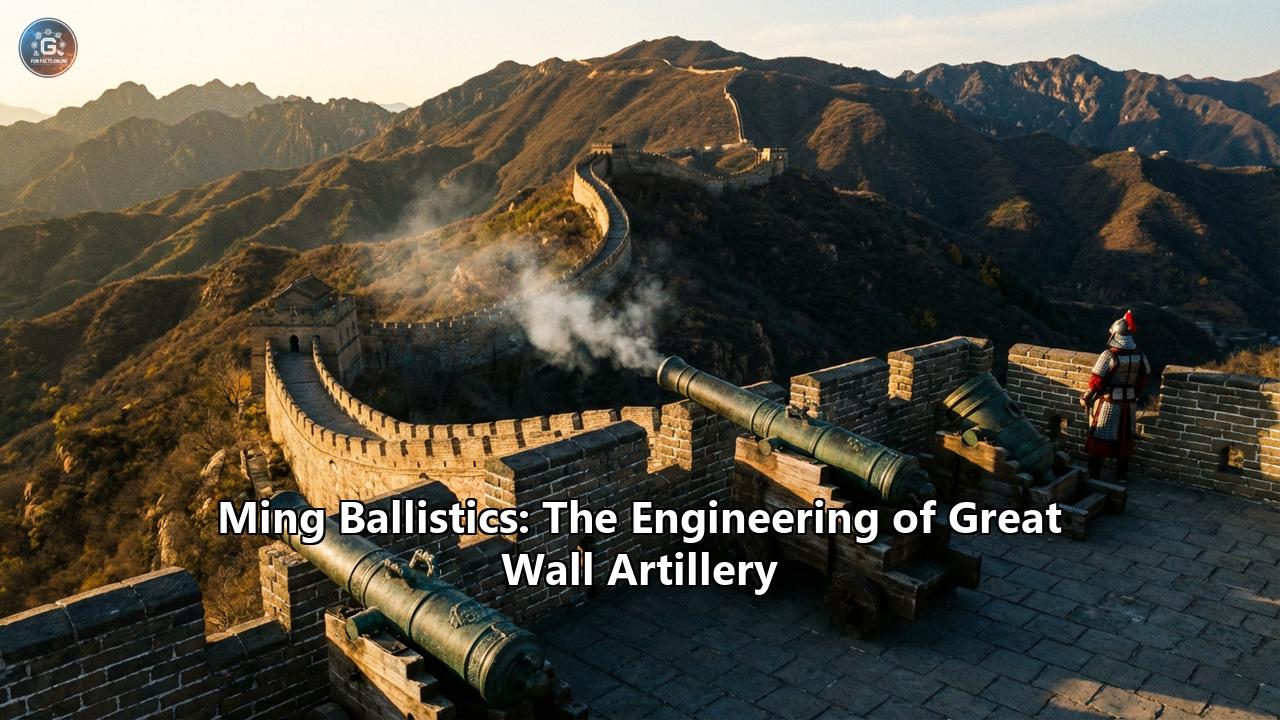

When we stand upon the Great Wall of China today, we see a monument of stone and brick, a serpentine dragon winding through the mist of the Yan Mountains. It is silent, save for the wind and the chatter of tourists. We touch the grey bricks and imagine the clashing of swords, the twang of bowstrings, and the thunder of hooves. But this romanticized view of cold steel and stone misses the true engineering marvel that kept the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) secure for nearly three centuries. By the mid-Ming era, the Great Wall was not just a physical barrier; it was a colossal, integrated machine of ballistic warfare. It was the world's largest artillery platform.

To understand the Great Wall as the Ming engineers intended, one must look past the masonry and see the smoke. One must smell the sulfur. This was a fortification designed not just to block, but to blast. From the chemical composition of their gunpowder to the complex metallurgy of their composite cannons, the Ming military industrial complex achieved feats of engineering that rivaled—and in some specific technologies, predated—their European counterparts. This is the story of how the Ming turned the Great Wall into a line of fire.

Part I: The Chemical Engine – Gunpowder Engineering

The soul of Ming artillery was not the iron barrel, but the black powder within it. By the time the Ming Dynasty rose to power, gunpowder was no longer a mystical "fire drug" of Taoist alchemists; it was a standardized industrial product, engineered for specific ballistic properties.

The Huolongjing RecipesIn the 14th century, the military treatise Huolongjing (Fire Drake Manual), co-authored by Jiao Yu and Liu Bowen, laid out the state of the art. Unlike early gunpowder which was low in nitrate and used primarily for incendiary effects (burning things), Ming gunpowder had evolved into a high-explosive propellant.

Historical analysis of Ming records reveals a sophisticated understanding of stoichiometry. The Ming engineers had determined that different weapons required different "burn rates."

- Explosive Powder: For bombs and heavy cannon shot, the ratio approached the theoretical ideal (roughly 75% saltpeter, 10% sulfur, 15% charcoal). This created a supersonic detonation wave necessary to shatter iron casings or propel a heavy ball at Mach speeds.

- Propellant Powder: For rockets and fire lances, the mixture was "slower," with slightly less saltpeter and often mixed with binders like honey or oil to prevent the powder from cracking and exploding the barrel prematurely.

One of the most critical, yet often overlooked, engineering breakthroughs of the Ming was the widespread adoption of "corned" powder. Early gunpowder was a fine meal, like flour. It absorbed moisture easily and packed down into a solid cake at the bottom of a barrel, which would often fail to ignite or burn too slowly to generate thrust.

Ming arsenals began processing gunpowder into wet cakes, which were then broken into small, uniform grains or "corns." This physical engineering had two massive effects:

- Aeration: The gaps between the grains allowed the flame to spread instantly through the entire charge, creating a more powerful and consistent explosion.

- Durability: Corned powder was more resistant to the humidity of the mountain passes where the Great Wall stood.

The Ming artilleryman didn't just pour black dust into his gun; he loaded graded, industrial-strength propellant that had been chemically optimized for the specific caliber of his weapon.

Part II: The Metallurgical Leap – From Iron to Composite

The greatest challenge for early artillery engineers was not making a gun that could fire, but making a gun that wouldn't kill its crew. Cast iron is brittle; bronze is expensive. The Ming engineers, facing the massive industrial scale of arming the Great Wall, had to solve this material science puzzle.

The Early Cast Iron DilemmaIn the early Ming (Hongwu reign), cannons were typically cast iron. While the Chinese were masters of iron casting—having used blast furnaces centuries before the West—large iron guns were prone to bursting under the immense pressure of the improved gunpowder. A micro-fracture invisible to the naked eye could turn a cannon into a fragmentation grenade.

The Composite Cannon RevolutionIn the late Ming, specifically under the guidance of reformist officials like Xu Guangqi and Sun Yuanhua, Chinese foundries began producing the "Dingliao Grand General" and other composite cannons. This was a stroke of metallurgical genius.

The technique involved a wrought iron core surrounded by a cast bronze exterior.

- The Core: Wrought iron is tough and malleable; it doesn't crack easily. It formed the liner of the barrel.

- The Shell: Bronze is easy to cast and resistant to corrosion. It formed the heavy outer body.

The engineering process was complex. The smiths would first forge the iron liner. Then, they would place this liner inside a clay mold and pour molten bronze around it. The critical engineering challenge was thermal expansion—if the metals cooled at different rates, they would separate. Ming founders used a technique involving cooling water introduced into the hollow core during casting. This forced the iron liner to cool and contract before the bronze shell, ensuring that as the bronze cooled and shrank, it would tightly grip the iron core, creating a pre-tensioned barrel capable of withstanding enormous chamber pressures.

This "shrink-fit" technology is similar in principle to how modern artillery barrels are autofrettaged today.

Part III: The Arsenal of the Wall

The Great Wall was not defended by a single type of gun. It was a layered defense system utilizing a diverse ecosystem of artillery, each engineered for a specific tactical role.

1. The Crouching Tiger (Hudunpao)Think of this as the Ming equivalent of a modern mortar. It was a short, thick-barreled cannon, often cast in iron, supported by two front legs and a rear spade, giving it the appearance of a crouching tiger.

- Engineering: It required no heavy carriage. It could be carried by two men.

- Ballistics: It fired a spray of small pellets or a single large stone/iron ball in a high arc.

- Tactical Use: Perfect for the Great Wall's terrain. Defenders could place these in the hollow watchtowers and fire over the battlements at enemies clustered at the base of the wall, in the "dead zones" that direct-fire guns couldn't reach.

Introduced to China via the Portuguese in the early 1500s, the Ming engineers essentially reverse-engineered and mass-produced this weapon, making it their own.

- The Breech-Loading Mechanism: The Folangji was a swivel gun that used pre-loaded sub-chambers. A gunner could fire, remove the spent chamber, insert a fresh one, and fire again in seconds.

- Rate of Fire: While it lacked the range of heavy cannons, its machine-gun-like rate of fire made it devastating against massed Mongol cavalry charges.

- Wall Integration: These were small enough to be mounted in the window embrasures of the watchtowers, providing flexible, rapid fire capability.

This was the heavy hitter. Based on Dutch and English culverins recovered from shipwrecks or purchased in Macau, these were long-barreled, muzzle-loading guns.

- Specifications: Weighing up to 1,800 kg (4,000 lbs), with a caliber of 11-13 cm.

- Range: These guns could fire a 10-pound iron ball over 2 to 5 kilometers with lethal accuracy.

- The Sight: Unlike earlier Chinese guns which relied on intuition, the Hongyipao were equipped with bead sights and adjustable trunnions, allowing for mathematical aiming calculations using quadrants.

Part IV: Ballistics and the Mathematics of Doom

Engineering a gun is one thing; hitting a moving target from a mountain ridge is another. The late Ming saw a transformation in military mathematics, driven largely by the translation of Western texts by Xu Guangqi and his collaboration with Jesuit missionaries.

The Parabolic ArcEarly Chinese artillery doctrine often focused on "direct fire"—pointing the gun at the target. But the Hongyipao, with its immense range, required an understanding of parabolic trajectories. The Ming artillery manuals began to include tables that correlated the angle of elevation with distance.

The Telescope and the QuadrantRecent archaeological finds and textual analysis suggest that by the Chongzhen reign (1627–1644), Ming officers were using telescopes (imported and domestically copied) to spot targets at ranges previously invisible to the naked eye. Combined with the gunner's quadrant—a tool used to set the precise angle of the barrel—artillery fire became a science.

Ming gunners learned to calculate "deflection"—adjusting for the wind whipping through the mountain passes. They used the "three points and one line" method for the Folangji, but for the heavy siege guns, they relied on geometric calculation, turning the Great Wall into a giant, mathematically calibrated instrument of destruction.

Part V: Civil Engineering – The Wall as a Platform

We often think of the Great Wall's structure as static. However, under the supervision of General Qi Jiguang in the 16th century, the Wall underwent a massive architectural retrofit to accommodate the gunpowder age.

The Hollow WatchtowersBefore Qi Jiguang, many wall fortifications were solid platforms. Qi designed and built over 1,000 "hollow enemy towers." These were essentially multi-story bunkers.

- The Middle Floor: This was the gun deck. It featured embrasures (windows) specifically widened and angled to allow the traverse of swivel guns and culverins.

- Ventilation: The engineers included specific vent shafts. In a confined stone room, the smoke from black powder could suffocate the crew. The draft created by the window placement and roof vents was calculated to clear the air rapidly during a firefight.

How do you get a 2,000-pound Hongyipao up a 45-degree mountain slope? This was a triumph of logistics engineering.

- Ramps and Capstans: The Ming built "horse ramps" (gradual slopes) on the inner side of the wall. For the steepest sections, they installed windlasses (heavy winches) at the top of the towers.

- Modular Transport: The smaller guns were designed to be broken down. The Folangji could be separated into the barrel, the mount, and the chamber.

- Storage: The towers served as ammunition dumps, keeping the powder dry and the iron shot rust-free, solving the supply chain issue of fighting in remote mountains.

Part VI: The Test – The Battle of Ningyuan (1626)

The engineering theories were put to the ultimate test in the winter of 1626 at Ningyuan. The Manchu leader Nurhaci, the architect of the rising Qing state, swept down with an unstoppable army of 130,000, known for their invincible "Iron Cavalry."

Defending the city was Yuan Chonghuan, a scholar-general who had bet everything on the new technology. He had fortified the city walls not just with height, but with 11 Hongyipao cannons, positioned on projecting bastions (a Western-influenced design advocated by Sun Yuanhua) that allowed for crossfire.

The Engineering VictoryWhen the Manchu cavalry charged, they expected the usual rain of arrows. Instead, they were met with solid iron balls fired at supersonic speeds.

- Kinetic Energy: The heavy shot didn't just kill the man it hit; it plowed through ranks of armored cavalry, shattering bone and armor alike.

- Psychological Shock: The Manchus had never faced weapons of this range and volume. The roar of the guns, amplified by the city walls, was deafening.

Nurhaci himself was wounded by a cannon blast—likely shrapnel or the concussive force of a nearby impact—and died months later. The "barbarian" technology, engineered and adapted by the Ming, had saved the dynasty. It was the first time in Chinese history that artillery had decisively determined the outcome of a major strategic siege.

Part VII: Legacy and Archaeology

The Ming eventually fell, not because their engineering failed, but because of internal rebellion, economic collapse, and political rot. When the Qing Dynasty took over, they inherited the Ming's arsenal. In fact, the "Red Coat Cannons" (renamed to avoid the slur "barbarian") became the backbone of the Qing military expansion.

Modern DiscoveriesIn recent years, archaeologists working on the Jiankou and Badaling sections of the Great Wall have unearthed the physical proof of this engineering prowess.

- The Inscriptions: Cannons found in the rubble bear detailed inscriptions: the name of the supervising official, the weight of the gun, the date of casting, and even the name of the smith. This reveals a rigorous quality control system. If a gun burst, the government knew exactly who to execute.

- The Slag: Analysis of iron slag found near the wall garrisons shows high-temperature blast furnace processing, confirming the industrial scale of local production.

Conclusion

The Great Wall of China is often called a "Stone Dragon." But if we look closer, through the lens of engineering and history, we see that by the 16th century, it had become an Iron Dragon. It was a complex, integrated weapon system that combined advanced chemistry, cutting-edge metallurgy, and ballistic mathematics.

The Ming engineers did not just pile stones; they weaponized the landscape. They turned the mountains into a fortress of geometry and gunpowder, holding back the tide of history with the roar of the Hongyipao. The survival of the dynasty for those final turbulent decades was not a miracle; it was a triumph of ballistics.

Reference:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gunpowder_weapons_in_the_Ming_dynasty

- https://www.chemeurope.com/en/encyclopedia/History_of_gunpowder.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hongyipao

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artillery

- https://www.reddit.com/r/todayilearned/comments/1ipg7uo/til_in_1530_the_chinese_ming_dynasty_invented/

- https://wap.lnd.com.cn/licc/system/2023/04/24/030401894.shtml

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_gunpowder

- http://www.visit-greatwall.com/a/WhatWastheLogisticsSupportSystemoftheAncientGreatWall.html

- https://world.taobao.com/lang/en-us/goods/-100108113253.htm