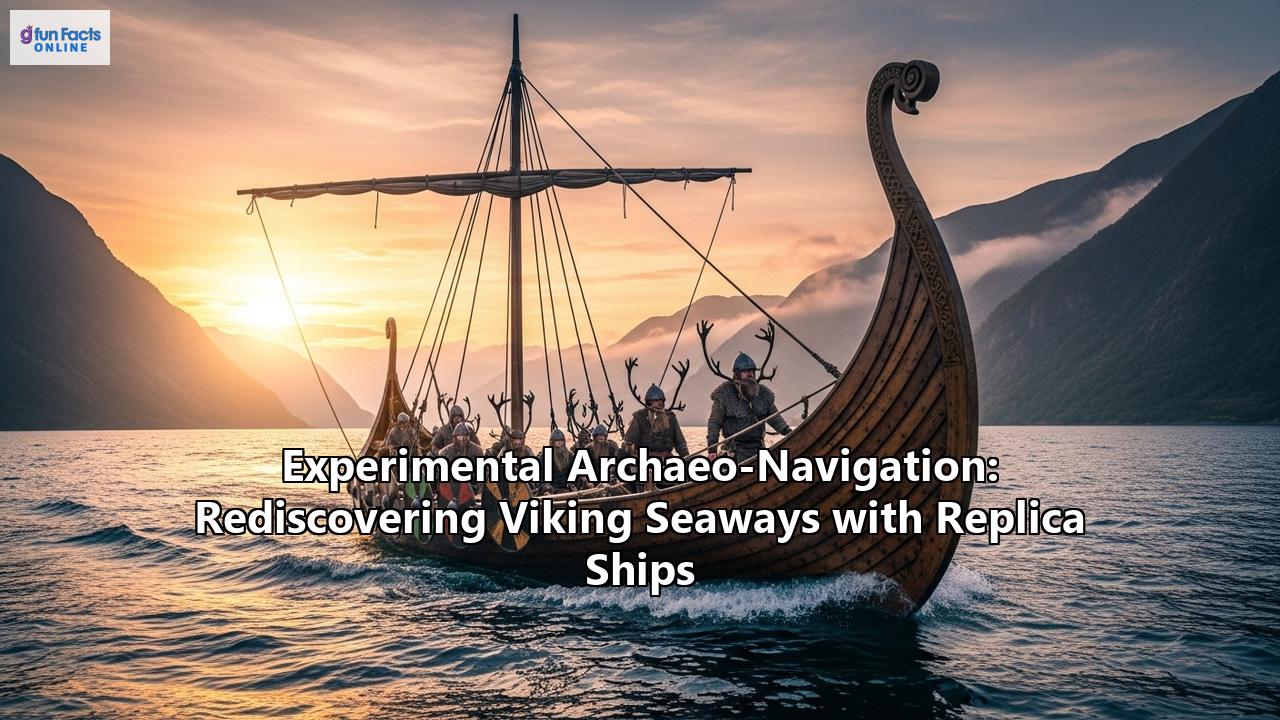

The wind whips across the deck, tasting of salt and distant lands. The rhythmic creak of timber and the snap of a square sail are the only sounds besides the crashing of waves against the clinker-built hull. This isn't a scene from a historical drama; it's the reality for modern-day adventurers and archaeologists who are taking to the high seas in meticulously reconstructed Viking ships. This is experimental archaeo-navigation, a field that breathes life into the past, seeking to understand how the Norse seafarers, with their seemingly simple technology, managed to dominate the North Atlantic for three centuries.

These voyages are more than just thrilling expeditions; they are floating laboratories. By building and sailing replica ships, researchers are gaining invaluable insights into Viking shipbuilding techniques, their astonishing navigational skills, and the sheer endurance of the crews who ventured into the unknown.

Rebuilding the Legendary Longships

The journey begins not at sea, but in the shipyard. The construction of a Viking replica ship is a monumental undertaking in itself, a testament to the skill of ancient craftspeople. Modern shipwrights work with copies of Viking Age tools, using axes and adzes instead of saws to shape the timbers, leaving characteristic tool marks that match archaeological finds.

The ships are built using the clinker technique, where overlapping planks are riveted together, creating a hull that is both strong and flexible, capable of withstanding the punishing waves of the open ocean. This method also resulted in a lightweight vessel with a shallow draft, a crucial advantage that allowed the Vikings to navigate up rivers and beach their ships on shores without established harbors.

One of the most ambitious reconstructions is the "Sea Stallion of Glendalough," a 100-foot-long warship based on the Skuldelev 2 ship, originally built in Ireland around 1042. The Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, Denmark, which has been at the forefront of this research for over four decades, has reconstructed all five of the Skuldelev ships, each providing new information about their specific functions, from coastal traders to formidable warships. The process is one of experimental archaeology, where each reconstruction is considered a suggestion of how the original ship might have appeared and performed.

Navigating by Sun, Stars, and Stone

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of these experimental voyages is the rediscovery of Viking navigational methods. Long before the advent of the magnetic compass, Norse sailors possessed a sophisticated understanding of the natural world. They used a variety of tools and techniques to find their way across vast, featureless expanses of water with surprising accuracy.

The Sun Compass: During the day, the sun was their primary guide. Archaeologists have discovered fragments of what is believed to be a "sun compass," a wooden disc with a central pin (gnomon). By observing the shadow cast by the gnomon on carved lines, navigators could determine the cardinal directions. Modern experiments have confirmed that this tool is remarkably effective for navigating on the open ocean, provided the sun is shining. Celestial Navigation: At night, the Vikings turned to the stars. The North Star, Polaris, served as a fixed point to determine latitude and maintain a consistent course. They also possessed a deep knowledge of star paths, tracking the movements of constellations to estimate their position and direction. The Enigmatic Sunstone: But what happened on the famously overcast and foggy days of the North Atlantic? The Icelandic Sagas speak of a mysterious "sunstone," a crystal that could reveal the sun's position even when it was hidden by clouds. While initially met with skepticism by some historians, experimental physicists have demonstrated that certain crystals, like calcite (also known as Iceland spar), can polarize light. By holding the stone to the sky and rotating it, a navigator could detect the pattern of polarized light and pinpoint the sun's location. Modern experiments have shown that this method can be surprisingly accurate, even at twilight.The Realities of a Viking Voyage

Life aboard a replica Viking ship is a stark reminder of the hardships faced by ancient mariners. Crews endure wet and cold conditions with only woolen blankets and crude sleeping bags for comfort, as the ships lack any form of cabin or superstructure. These voyages are a true test of endurance, requiring not only physical strength for rowing and sailing but also immense social skills. As one modern-day Viking archaeologist noted, a cooperative and resilient crew is just as crucial as a seaworthy vessel.

Modern expeditions, while striving for authenticity, often incorporate some modern safety equipment, such as satellite phones and modern navigation devices, as a precaution. However, the core experience remains true to the spirit of the Vikings. Crews often have to fish for their food due to limited space on board. They face the same challenges of unpredictable weather, powerful currents, and the ever-present danger of being driven onto rocks.

One of the most famous modern voyages was that of the "Draken Harald Hårfagre," the world's largest Viking ship replica, which successfully crossed the Atlantic in 2016, following the ancient route from Norway to Iceland, Greenland, and finally North America. This and other expeditions, like the journey of the "Odin's Raven" in 1979, have captured the public imagination and provided invaluable data for researchers.

Rewriting History, One Voyage at a Time

Experimental archaeo-navigation is more than just an adventure; it's a vital research method that is actively reshaping our understanding of the Viking Age. These voyages have provided practical insights that cannot be gleaned from archaeological finds alone. For instance, recent expeditions have suggested that Vikings may have ventured farther from the coast than previously thought and utilized a decentralized network of smaller, more accessible harbors.

The ongoing construction and sailing of these replica ships continue to provide valuable new insights into a vibrant period of maritime history. They are a powerful reminder of the ingenuity and resilience of the Vikings, who, with their magnificent ships and mastery of the seas, truly were the lords of the northern ocean. As these modern-day adventurers follow in their wake, they are not just reliving history, they are rediscovering it.

Reference:

- https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0293816

- https://world.expeditions.com/expedition-stories/stories/north-atlantic-sea-roads-enduring-legacy-of-viking-ship

- https://vikingsrule.com/navigation-mapping-routes/

- https://www.battlemerchant.com/en/blog/rediscovery-of-the-sunken-viking-fleet-of-roskilde-an-insight-into-the-maritime-power-of-the-vikings

- https://www.sciencenordic.com/denmark-greenland-science-special-society--culture/replica-viking-ship-will-recreate-norse-voyages-in-greenland/1433882

- https://exarc.net/issue-2012-1/mm/book-review-sailing-past-learning-replica-ships-jenny-bennett-ed

- https://www.vikingeskibsmuseet.dk/en/visit-the-museum/exhibitions/the-five-reconstructions

- https://www.amscan.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/SR_Autumn16_Viking_Ships_article.pdf

- https://www.studysmarter.co.uk/explanations/history/viking-history/viking-navigation/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3049005/

- https://www.vikingeskibsmuseet.dk/en/professions/education/knowledge-of-sailing/instrument-navigation-in-the-viking-age

- https://tripleviking.com/blogs/news/how-did-vikings-use-stars-for-time-and-navigation

- https://philipball.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Viking-sunstones.pdf

- https://www.foxnews.com/travel/archaeologist-uncovers-viking-secrets-epic-three-year-journey-sea

- https://hakaimagazine.com/article-short/modern-day-viking-voyage/

- https://globalnews.ca/news/2737227/worlds-largest-modern-day-viking-ship-arrives-in-canada-after-6-week-transatlantic-journey/

- https://www.yahoo.com/news/archaeologist-sailed-viking-replica-boat-184752172.html