Introduction: The Breathing Abyss

For centuries, human understanding of the deep ocean was shrouded in a silence as profound as the darkness that fills it. We imagined the abyssal plains—the vast, flat expanses of the ocean floor sitting 4,000 meters beneath the surface—as a graveyard of the world above. We believed that life there was a mere scavenger, surviving on "marine snow," the drifting detritus of dead plankton and fecal matter falling from the sunlit surface. Most crucially, we held an unshakeable scientific dogma: the oxygen that sustains all aerobic life on Earth, from the smallest copepod to the blue whale, is the exclusive product of photosynthesis. We believed that every breath taken in the deep sea was a loan from the sun, carried down by the slow, cold conveyor belt of global ocean currents.

In July 2024, that dogma was shattered.

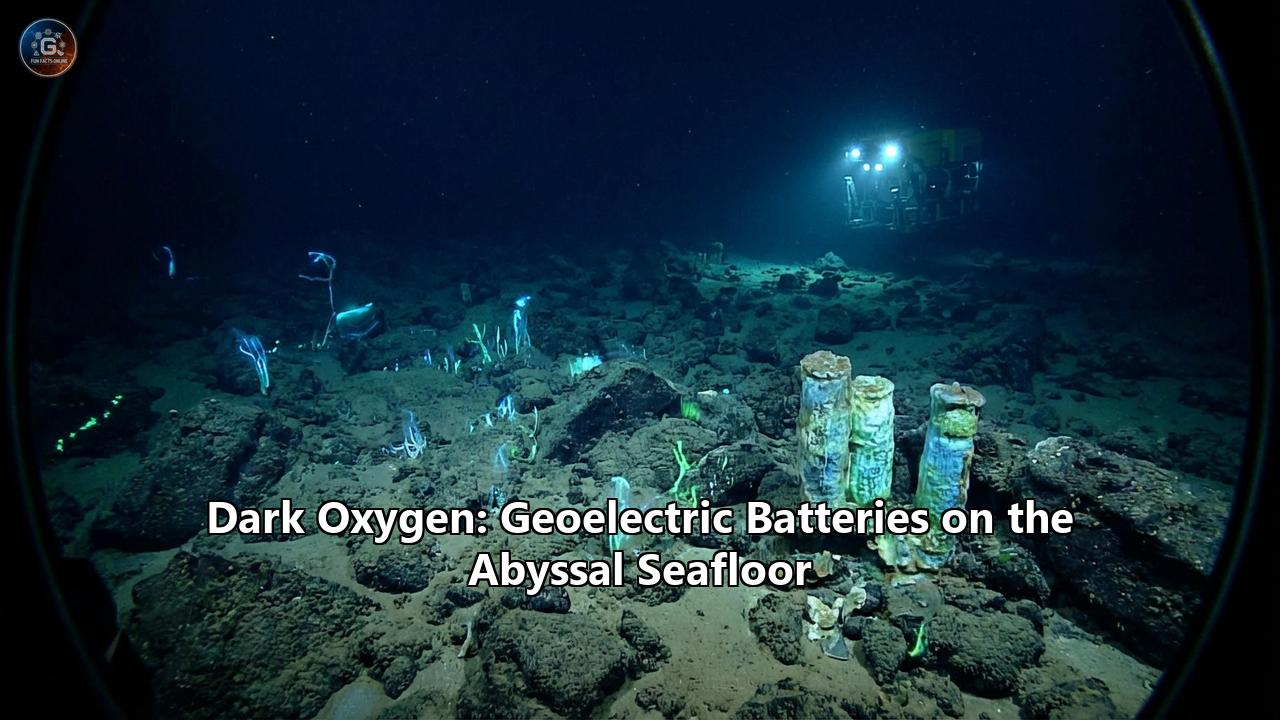

A team of scientists led by Professor Andrew Sweetman of the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS) published a paper in Nature Geoscience that fundamentally altered our understanding of planetary chemistry. They discovered that the deep ocean floor is not merely a consumer of oxygen but a producer of it. In the crushing darkness of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a region of the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico, oxygen is being generated without a single photon of sunlight.

This "dark oxygen" is not biological in origin. It is not the work of strange, chemosynthetic bacteria or undiscovered plants. It is electrochemical. The ocean floor is paved with trillions of potato-sized rocks known as polymetallic nodules. These nodules, rich in manganese, nickel, and cobalt, are effectively natural batteries. Through a process of seawater electrolysis, they are splitting water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen, turning the abyssal seafloor into a planetary-scale geoelectric power plant.

This discovery is more than a scientific curiosity; it is a revelation that touches upon the origins of life on Earth, the potential for life on other worlds, and the immediate, volatile future of the human economy. As mining companies rev their engines to harvest these nodules for the batteries in our electric vehicles, we are faced with a stark realization: the "green energy" transition might necessitate destroying the very batteries that breathe life into the deep ocean.

Part I: The Impossible Signal

The Sensor That "Failed"

The story of dark oxygen begins not with a "eureka" moment, but with a decade of frustration. In 2013, Andrew Sweetman was aboard a research vessel in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, conducting what was supposed to be a routine survey of benthic respiration. The methodology was standard: researchers deploy "benthic landers"—large, tripod-like frames equipped with sensors—that sink to the seafloor. Once there, these landers drive cylindrical chambers into the sediment, isolating a small patch of the ocean floor and the water immediately above it.

Over 24 to 48 hours, sensors inside the chambers measure the concentration of dissolved oxygen. In every previous experiment conducted in the history of oceanography, the result was a downward slope. Marine organisms—bacteria, worms, crustaceans—consume the oxygen in the chamber, and the levels slowly drop. Respiration is the rule of life.

But in 2013, Sweetman’s sensors showed the opposite. The oxygen levels didn’t fall; they rose.

"I told my students to put the sensors back in the box and ship them back to the manufacturer," Sweetman later recounted. "I just thought they were broken."

It was a reasonable assumption. In the absence of light, photosynthesis is impossible. Therefore, oxygen production should be impossible. For ten years, Sweetman and his team observed this "impossible" signal across multiple expeditions. They recalibrated their instruments. They used different sensor technologies—optical optodes, electrochemical sensors—to rule out hardware bias. They questioned their sanity. But the data remained stubborn. In the cold, dark silence of the CCZ, something was exhaling.

The 2024 Breakthrough

The turning point came when the team decided to stop treating the data as an error and started treating it as a phenomenon. They returned to the CCZ with a specific hypothesis: if the oxygen isn't coming from biology, it must be coming from the geology.

The primary geological feature of the CCZ is the polymetallic nodule. These black, knobbly concretions cover the seafloor in densities so high they sometimes touch one another, looking like a cobblestone street paved by a chaotic giant. To test their hypothesis, the team conducted "ex situ" experiments on the ship. They collected nodules and seabed sediment, placed them in seawater chambers under controlled conditions, and killed off all biological activity using mercury chloride. If the oxygen production was biological, the poison would stop it.

The oxygen levels continued to rise.

The production was abiotic. The "dead" rocks were creating life-giving gas. The team realized they were looking at a natural form of electrolysis—the splitting of water ($H_2O$) into hydrogen ($H_2$) and oxygen ($O_2$) using electricity. But for electrolysis to occur, there must be a voltage source. The team brought in Franz Geiger, a chemist from Northwestern University, to measure the electrical potential of the nodules.

What Geiger found was startling. A single nodule could generate a surface voltage of up to 0.95 volts. While seawater electrolysis typically requires about 1.5 volts to initiate, the team hypothesized that in the natural environment, where nodules are clustered together in the trillions, they act in series like batteries in a flashlight. The combined potential of clustered nodules could easily breach the 1.5-volt threshold, cracking open water molecules and releasing oxygen into the deep.

They had discovered the world's first "geobattery."

Part II: The Science of the Geobattery

Anatomy of a Nodule

To understand how a rock becomes a battery, we must look inside it. Polymetallic nodules are not formed by volcanoes or rapid geological events. They are the product of slow, excruciatingly patient accretion over millions of years.

A nodule begins with a nucleus—a shark’s tooth, a fragment of shell, or a piece of basalt debris. Over eons, dissolved metals in the seawater and sediment pore water precipitate onto this nucleus. The growth rate is almost incomprehensibly slow: hydrogenetic nodules (those precipitating directly from seawater) grow at a rate of 2 to 5 millimeters per million years. A nodule the size of a potato might be 10 million years old, a silent witness to the drift of continents and the rise and fall of dinosaurs.

The nodules are composed primarily of manganese and iron oxides, but they are sponges for other metals. They contain high concentrations of nickel, copper, cobalt, molybdenum, rare earth elements, and lithium. Structurally, they are built of concentric layers, like an onion. These layers are dominated by specific manganese minerals, most notably vernadite, birnessite, and todorokite.

The Electrochemical Mechanism

The "battery" effect arises from the difference in electrical potential between the different layers of metals. The term "redox" refers to reduction (gaining electrons) and oxidation (losing electrons). The complex stratification of metals within the nodule creates a natural electrochemical gradient.

- Birnessite ($MnO_2$): This mineral consists of sheets of manganese oxide with water and metal cations (like $Na^+$ or $Ca^{2+}$) sandwiched between them. It is highly reactive and conductive.

- Todorokite: This mineral has a tunnel-like structure, allowing ions to move through it.

The researchers propose that the high concentration of metal ions, combined with the irregular distribution of oxidized and reduced layers (manganese oxides vs. iron hydroxides), creates a permanent potential difference across the nodule's surface. When the nodule is submerged in seawater (a highly conductive electrolyte), this potential difference drives a current.

The chemical reaction on the surface of the nodule is effectively a half-cell reaction. At the anode-like regions of the nodule surface, water is oxidized:

$$2H_2O \rightarrow O_2 + 4H^+ + 4e^-$$

This releases molecular oxygen ($O_2$) and protons ($H^+$). The electrons ($e^-$) travel through the conductive body of the nodule to a cathode-like region, where a reduction reaction occurs (likely the reduction of manganese or oxygen consumption elsewhere, though the net result is a surplus of oxygen in the immediate vicinity).

The implication is staggering: the seafloor is not inert rock. It is a charged, active surface. The CCZ is essentially a 4.5 million square kilometer electric grid, humming with a silent voltage that has been running for millions of years.

Part III: The Ecosystem of the Dark

Life in the CCZ

Before this discovery, we viewed the oxygen in the deep sea as a finite resource, slowly depleting as it traveled from the poles. Now, we must consider that the deep sea has a local life-support system. The organisms of the CCZ are not just surviving in a desert; they are living in an oasis of electrified oxygen.

The biodiversity of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone is exceptionally high. Recent surveys have identified over 5,000 species in the region, with nearly 90% of them being new to science. This is not a barren mudflat; it is a thriving, alien rainforest.

- The Gum Squirrel (Psychropotes longicauda): A bizarre, violet sea cucumber with a long, tail-like appendage that acts as a sail, allowing it to drift across the sediment.

- The "Casper" Octopus: A ghostly, translucent octopod that lays its eggs on the stalks of dead sponges—sponges that grow exclusively on the hard substrate of the nodules.

- Xenophyophores: These are among the strangest creatures on Earth. They are single-celled organisms (protists) that grow to massive sizes—some as large as a dinner plate. They build delicate, intricate "tests" (shells) out of sediment and glue. Xenophyophores are known to have high concentrations of heavy metals inside their cells, and they are found in high abundance in nodule fields. It is now speculated that they might be congregating around nodules not just for the hard surface, but to bathe in the excess oxygen generated by the geobatteries.

- Porifera (Sponges): Species like Bolosominae and the glass sponge Hyalonema anchor themselves to the nodules. In the soft, abyssal mud, a nodule is the only solid thing to hold onto. If you remove the nodule, you remove the anchor, and the sponge dies.

The "Dark Oxygen" Dependency

The discovery of dark oxygen forces a re-evaluation of the carrying capacity of the deep sea. We previously calculated the metabolic limits of this ecosystem based on oxygen advection (currents moving oxygenated water). If there is a local source producing significant amounts of oxygen, the biomass here might be higher than our models predict.

More critically, some organisms might be "obligate" beneficiaries of this process. Microbes living directly on the surface of the nodules might be feeding off the energy gradient or the oxygen itself. The interface between the nodule and the sediment—where the voltage potential might be highest—could be a hotspot for microbial life that forms the base of the food web for the larger megafauna like the Oneirophanta mutabilis sea cucumbers that graze on the sediment.

Part IV: Rewriting the Origins of Life

The Chicken and the Egg

For decades, the standard model of evolutionary biology has been:

- Life begins in anoxic (oxygen-free) conditions.

- Cyanobacteria evolve photosynthesis ~2.5 billion years ago (the Great Oxidation Event).

- Oxygen floods the atmosphere and oceans.

- Aerobic (oxygen-breathing) complex life evolves.

The discovery of dark oxygen throws a wrench into this timeline. If natural geobatteries can produce oxygen without light, then "pockets" of oxygenated water could have existed on the primordial Earth long before the evolution of photosynthesis.

Professor Sweetman suggests this requires us to ask: "Where could aerobic life have begun?" It is possible that the first aerobic organisms didn't evolve in the sunlit shallows, but in the dark, electrified depths, clinging to charged rocks that provided a steady stream of electron acceptors (oxygen). This reverses the arrow of evolutionary pressure; rather than life terraforming the planet to create oxygen, the planet might have provided oxygen batteries that invited life to adapt to them.

Implications for Astrobiology

The implications extend beyond Earth. We are currently searching for life on the "Ocean Worlds" of our solar system—specifically Enceladus (a moon of Saturn) and Europa (a moon of Jupiter). Both have subsurface oceans of salty water beneath kilometers of ice. Sunlight cannot reach these oceans.

Until now, astrobiologists assumed that any life there would have to be anaerobic (living without oxygen) or rely on very limited chemical sources of energy. However, if polymetallic nodules or similar mineral formations exist on the floors of the Europan or Enceladean oceans, they could be generating "dark oxygen" via electrolysis.

This changes the odds. Oxygen is a high-energy molecule; it allows for high-metabolism, complex animal life. If Enceladus has geobatteries, it doesn't just have the potential for slime molds—it has the potential for fish, squid, or complex ecosystems that we can scarcely imagine. The "habitable zone" of the universe just got significantly larger and darker.

Part V: The Battle for the Seabed

The Green Dilemma

This discovery has crashed violently into the world of human economics. The polymetallic nodules of the CCZ are the target of the nascent deep-sea mining industry. The reason is simple: they are packed with the exact metals needed to build the batteries for the "Green Transition."

- Cobalt: Essential for stability in lithium-ion batteries.

- Nickel: Critical for high-energy density cathodes.

- Copper: The backbone of all electrical wiring.

- Manganese: Used in steel and increasingly in NCM (Nickel-Cobalt-Manganese) batteries.

The narrative of the mining industry, led prominently by The Metals Company (TMC), is one of ethical trade-offs. They argue that terrestrial mining (in rainforests of Indonesia or the Congo) involves child labor, deforestation, and massive toxic tailings. Deep-sea mining, they claim, is cleaner: you simply vacuum up the nodules from the barren desert of the seafloor. No trees to cut, no people to displace.

Gerard Barron, the CEO of TMC, has famously referred to the nodules as "batteries in a rock." The irony is now palpable: they literally are batteries.

The Industry Strikes Back

The publication of Sweetman’s paper was met with immediate and fierce pushback from the mining industry. The Metals Company released a statement calling the research "flawed." Their primary critique—and one echoed by some other scientists in the field—centers on methodology.

The skepticism focuses on "trapped air." Critics argue that when the benthic landers are deployed, they might trap air bubbles from the surface in their chambers or tubing. As the lander descends and pressure increases, these bubbles could be forced into solution or slowly released, causing a false signal of rising oxygen. TMC points out that previous studies in the region over decades did not report this phenomenon (though Sweetman argues they simply ignored it as noise).

Furthermore, TMC-funded scientists argue that the voltage measured (0.95V) is insufficient to split water (1.23V - 1.5V required) unless the conditions are absolutely perfect, which they doubt occurs on a large scale in nature. They frame the "dark oxygen" finding as an experimental artifact rather than a planetary process.

The Regulatory War

The arbiter of this conflict is the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a UN-affiliated body based in Jamaica. The ISA is currently in the final stages of drafting the "Mining Code," the rulebook that will allow commercial extraction to begin.

The discovery of dark oxygen has weaponized the "Precautionary Principle." Over 30 countries, including Canada, France, and the UK, have called for a moratorium or a "precautionary pause" on deep-sea mining. The logic is: if we didn't know the seafloor produced oxygen until 2024, what else don't we know?

Environmental groups like Greenpeace and the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition argue that mining would not only destroy the habitat (the nodules themselves) but also shut off the oxygen supply for the deep sea. Sediment plumes from the mining robots could smother the nodules in adjacent areas, insulating them and stopping the electrolysis, effectively suffocating the ecosystem.

Part VI: Future Horizons

The scientific community is not waiting for the bureaucrats. New expeditions are already fueled and launching.

- Sweetman’s Return: Andrew Sweetman is planning a return to the CCZ in 2025/2026, backed by the Nippon Foundation and carrying new, specialized landers designed to rule out the "bubble" hypothesis once and for all. These landers will measure "seafloor respiration" with redundant sensors and better isolation protocols.

- The Industry’s Verification: The Metals Company and other contractors are also launching cruises to replicate (or debunk) the findings. The scientific method is being played out in real-time, with billions of dollars and the health of the ocean at stake.

The debate has moved beyond simple biology. It is now about the physics of the planet. If the seafloor is a battery, does it play a role in the global carbon cycle? Does it affect the acidity of the deep ocean? Does the hydrogen produced by the electrolysis fuel a different, parallel microbial ecosystem (hydrogen-eating bacteria) that we have missed entirely?

Conclusion: The Humility of the Deep

The discovery of Dark Oxygen is a humbling reminder of human ignorance. We have mapped the surface of Mars better than our own ocean floor. We were preparing to bulldoze an ecosystem we thought we understood, only to find—at the eleventh hour—that the rocks we wanted to crush were doing something magical.

We thought the deep ocean was a place of death, where life waited for crumbs from the table above. Instead, we found a power plant. We found that the abyss breathes on its own, powered by the slow, cold electricity of ancient metal.

As the ships gather above the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, waiting for the green light to lower their harvesters, the nodules sit in the dark, as they have for ten million years, silently cracking water molecules, creating the breath of the deep. Whether they will continue to do so, or whether they will end up in the battery of a sedan on a Los Angeles freeway, is the choice that humanity must now make.

Reference:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bGc1Z-BxKXY

- https://geoexpro.com/nodules-may-indeed-be-battery-rocks/

- https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/eng7.pdf

- https://earthjustice.org/article/deep-sea-mining-explained

- https://www.mdpi.com/2075-163X/14/1/47

- https://www.mdpi.com/2075-163X/10/10/884

- https://oceanographicmagazine.com/news/5000-new-species-found-in-clarion-clipperton-zone/

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/may/25/more-than-5000-new-species-discovered-in-pacific-deep-sea-mining-hotspot

- https://deepseamining.ac/article/2

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7nVnS8uExOo