Here is a comprehensive and detailed article about the Khirgisuur Monuments.

Khirgisuur Monuments: The Hidden Bronze Age Mounds of Mongolia

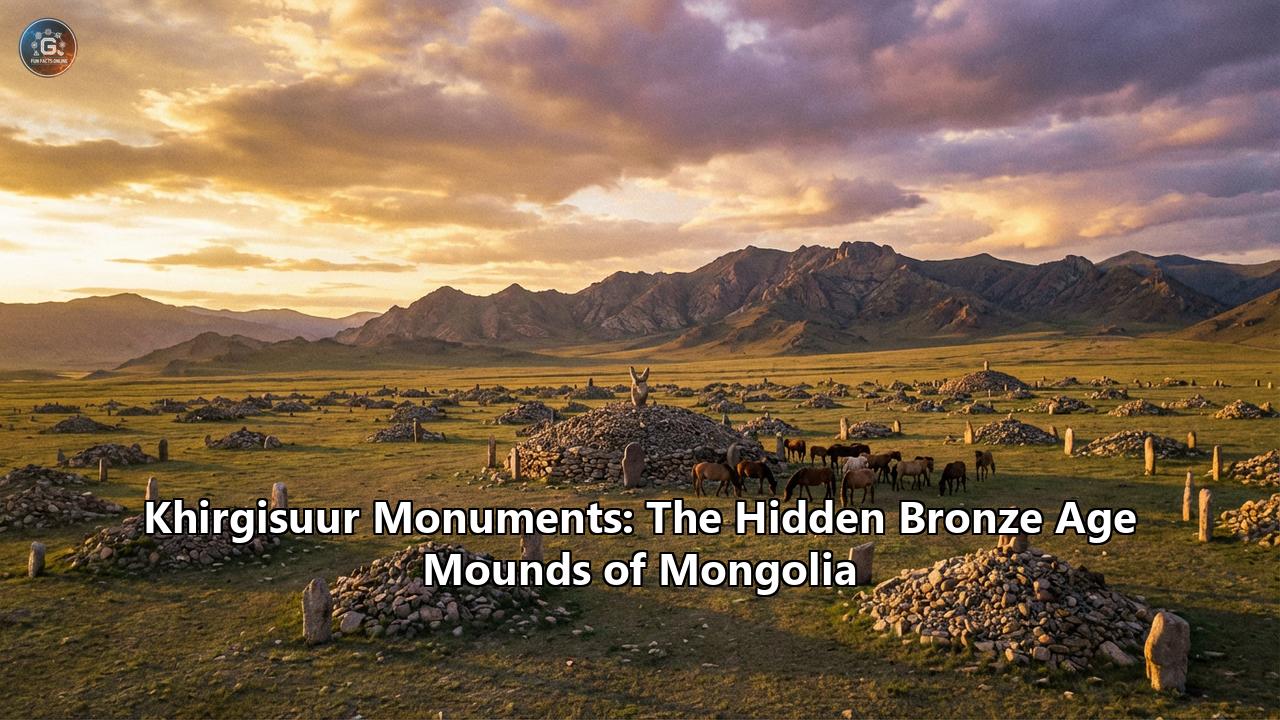

In the vast, windswept expanse of the Mongolian steppe, where the blue sky meets an endless horizon of green and gold, a silent army of stone watches over the landscape. These are not natural formations, nor are they the remnants of the famous Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan. They are far older, mysterious, and monumental. They are the

Khirgisuurs—complex stone mounds and ritual sites that date back three thousand years to the Late Bronze Age.For centuries, these enigmatic structures were overshadowed by the more visually striking "Deer Stones" that often accompany them. However, modern archaeology has revealed that the Khirgisuur is not just a pile of rocks; it is a sophisticated architectural marvel, a celestial calendar, a sacrificial altar, and a testament to a powerful, complex society of mobile pastoralists who dominated the Eurasian steppe long before the first word of history was written.

This article delves deep into the world of the Khirgisuurs, exploring their architecture, the mysterious people who built them, the bloody rituals they hosted, and their enduring legacy in the cultural landscape of Central Asia.

1. The Architecture of Immortality: What is a Khirgisuur?

The term

Khirgisuur (also spelled kheregsüür) is derived from the Mongolian word khirg or khirgis, which is often associated with the Kyrgyz people, though the monuments predate the historical Kyrgyz by nearly two millennia. To the untrained eye, a Khirgisuur might look like a simple cairn, but to the archaeologist, it is a diagram of the Bronze Age mind.These monuments are complex, multi-component structures that can cover areas ranging from a few meters to several hectares. A "classic" Khirgisuur consists of four distinct architectural elements, each serving a specific ritual or symbolic function.

The Central Mound (The Axis Mundi)

At the heart of every complex lies the central mound. Constructed from locally sourced stones—granite, basalt, or sandstone—these mounds can stand anywhere from one to four meters in height and span up to twenty meters in diameter. In some regions, the central mound covers a stone cist or a shallow pit.

- The Tomb vs. Cenotaph Debate: For decades, scholars believed these were exclusively tombs for elite chieftains. Indeed, some excavations have revealed human remains. However, a startling number of excavated mounds are empty or contain only fragmented bones. This has led to a leading theory that many Khirgisuurs are actually cenotaphs—memorials built for individuals whose bodies were lost in battle or who were buried elsewhere, or perhaps pure ritual centers where the "presence" of the ancestor was invoked without the physical body.

The Enclosure (The Sacred Boundary)

Surrounding the central mound is a geometric fence, constructed of large boulders or slab stones.

- Square vs. Circular: In the Altai region of western Mongolia, these fences are often circular, echoing the shape of the sun or the yurt (ger). In central Mongolia, square fences are equally common, potentially representing a different cosmological concept—perhaps the "four corners" of the earth.

- The Forbidden Zone: The space between the mound and the fence is usually devoid of artifacts, suggesting it was a sacred precinct, a "forbidden zone" where only specific rituals could take place.

The Radial Spokes (The Sun’s Rays)

One of the most visually striking features of many Khirgisuurs is the presence of stone rows radiating outward from the central mound to the enclosure fence. These "spokes" give the monument the appearance of a giant wheel or a sunburst when viewed from above (or via drone photography).

- Connectors: These rays physically connect the center (death/ancestors) to the periphery (life/the living).

- Solar Symbolism: The number of rays often varies—four, eight, or more—suggesting a connection to cardinal directions or solar cycles.

The Satellite Features (The Ring of Fire and Blood)

Beyond the enclosure fence lies the most archaeologically rich zone: the satellite mounds.

- Small Mounds: Dozens, sometimes hundreds, of smaller stone cairns dot the eastern and southern perimeter. These are the repositories of sacrifice, containing the skulls, neck vertebrae, and hooves of horses.

- Stone Circles: Interspersed with the mounds are small circles of stones, often filled with ash and burnt earth. These functioned as altars for burning offerings, primarily the meat of sheep and goats.

2. The Builders: Ghosts of the Grasslands

Who were the architects of these stone giants? For a long time, they were a ghost population. Unlike the sedentary civilizations of Egypt or Mesopotamia, the builders of the Khirgisuurs left behind no cities, no palaces, and no written texts. They were the Late Bronze Age Pastoralists of Mongolia (c. 1300–700 BCE).

The "Invisible" Civilization

Recent research, particularly in the Khanui River Valley, has sought the settlements of these people. The results were surprising: there were almost no permanent structures. The builders lived in ephemeral campsites, likely using felt tents similar to the modern Mongolian

ger. They moved seasonally with their herds, leaving behind only faint traces—pottery shards, hearths, and stone tools—buried under just a few centimeters of steppe soil.- Paradox of Power: The Khirgisuurs present a paradox. How could a society that lived in temporary tents and moved constantly organize the massive labor force required to move tons of stone and build thousands of monuments? The answer lies in communal cohesion. The construction of a Khirgisuur was likely a seasonal gathering event, a "festival of labor" that brought together dispersed clans to reaffirm their alliances and social hierarchy.

Diet and Lifestyle: Secrets in the Isotopes

Advanced isotopic analysis of human bones from this period has revolutionized our understanding of their daily life.

- The Milk Revolution: Analysis of dental calculus (plaque) has shown definitively that these people were heavy consumers of dairy products from sheep, goats, cattle, and horses. This "dairy pastoralism" was the technological breakthrough that allowed them to conquer the harsh, arid steppe.

- A Diet of Meat and Milk: Carbon and nitrogen isotope signatures confirm a diet rich in animal protein. They were true herders, relying almost entirely on their livestock for survival.

Genetic Origins

DNA studies reveal that these people were a blend of Ancient North Eurasians (ANE) and populations from the Altai-Sayan region. They show genetic continuity with the earlier populations of the steppe but also display the hallmarks of a booming population that was expanding its territory—an expansion driven by the horse.

3. The Deer Stone Connection: A Shared Sacred Landscape

It is impossible to discuss Khirgisuurs without mentioning their famous counterparts: the Deer Stones. These tall, granite stelae, carved with stylized images of flying deer, warriors, and weapons, are often found in the same valleys as Khirgisuurs.

The Deer Stone-Khirigsuur Complex (DSKC)

Archaeologists now group these two monument types under the Deer Stone-Khirigsuur Complex (DSKC). While they are distinct, they function together as part of a single ritual system.

- The Stone Body: The Deer Stone likely represents the human body of a warrior or chieftain—tattooed with deer, belted with weapons (daggers, axes, bows), and wearing earrings.

- The Stone House: The Khirgisuur represents the "house" or the ritual space for that spirit.

- Spatial Relationship: Interestingly, Deer Stones and Khirgisuurs are rarely found

4. Blood on the Steppe: The Rituals of Sacrifice

The most chilling and dramatic aspect of the Khirgisuur is the evidence of mass animal sacrifice. Excavations at major sites have uncovered a ritual practice of staggering scale and consistency.

The Horse Head Ritual

In the satellite mounds surrounding the main Khirgisuur, archaeologists consistently find the same specific skeletal parts of horses: the skull, the cervical vertebrae (neck), and the hooves.

- Directionality: Almost without exception, the horse snouts face East—towards the rising sun. This solar orientation was non-negotiable, indicating a strict religious adherence.

- The "Head and Hoof" Hide: The absence of ribs, legs, and pelvis suggests that the horse was not buried whole. Instead, the animal was likely skinned, with the head and hooves left attached to the hide. This "taxidermy" effigy was then placed in the mound. The meat was almost certainly consumed by the builders during the funeral feast.

The Scale of Slaughter: Urt Bulagyn

To understand the magnitude of this economy, one must look at the site of Urt Bulagyn in the Khanui Valley. This single, massive Khirgisuur is surrounded by approximately 1,700 satellite mounds.

- A Fortune in Horses: Each mound contains at least one horse. In a Bronze Age society, a horse was a Ferrari, a tractor, and a tank rolled into one. To sacrifice 1,700 horses at a single monument represents an accumulation of wealth that is mind-boggling. It suggests that the person honored here was a "Khan" of immense power, capable of commanding tributes from clans across a vast region.

The Burnt Altars

While horses were the prestigious offering for the dead, sheep and goats were the fuel for the living. The stone circles found near the horse mounds contain calcined (burnt) bits of sheep and goat bone. These were likely "burnt offerings"—the smoke designated for the heavens, while the meat was eaten by the hundreds of people gathered for the construction.

5. Case Studies in Stone: Exploring the Major Sites

While thousands of Khirgisuurs dot the Mongolian map, a few sites stand out for their size, preservation, and the secrets they have revealed.

1. Urt Bulagyn (The Giant)

Located in Arkhangai Province, this is the "Great Pyramid" of Khirgisuurs. Its central mound is massive, but its true glory is the field of satellite stones that stretches like a city around it. Excavations here proved that these massive complexes could be built relatively quickly—perhaps in a single season or a few years—implying a massive, coordinated workforce rather than centuries of slow accumulation.

2. Tsatsyn Ereg (The Open Air Museum)

This valley is a UNESCO World Heritage candidate site. It contains a stunning density of both Deer Stones and Khirgisuurs. Here, visitors can see the transition of the landscape—how the monuments were placed specifically to interact with the background mountains and the flow of the river. It is a masterpiece of "Landscape Archaeology."

3. Ulaan Tolgoi (The Northern Sentinel)

Located in the Khovsgol region near Lake Erkhel, Ulaan Tolgoi is famous for its well-preserved Deer Stones standing guard over Khirgisuur mounds. This site has provided crucial radiocarbon dates (c. 1200 BCE) that helped anchor the timeline of the entire culture.

4. The Oyut Discovery (2024)

As recently as 2024, geological surveys at the Oyut Deposit in central Mongolia uncovered ten previously unknown mounds. This discovery highlights how much of Mongolia's history is still hidden just beneath the surface, often brought to light only when modern industry (mining) intersects with ancient heritage.

6. Regional Variations: The Altai vs. The Center

Not all Khirgisuurs are the same. As one travels west from the grassy steppes of Arkhangai to the rugged peaks of the Altai Mountains, the monuments change.

Central Mongolia (The Heartland)

- Characteristics: Massive scale, square fences, thousands of horse sacrifices.

- Focus: Ostentatious display of wealth and hierarchy.

The Altai Region (The Western Frontier)

- Characteristics: Smaller, more elegant, "compass-like" designs. They often feature circular fences with wheel-like spokes.

- The Difference: Crucially, Altai Khirgisuurs rarely have the massive horse sacrifice mounds seen in the east. Instead, they might incorporate Deer Stones

7. Cosmology: A Map of the Universe?

Why were these monuments built? Beyond their function as graves or memorials, they likely served as cosmograms—maps of the universe as the Bronze Age herders understood it.

- The Center: The mound represents the world mountain, the center of the universe, or the entry to the underworld.

- The Fence: The boundary between the ordered world of humans and the chaotic wilderness.

- The Rays: The cardinal directions, connecting the site to the four winds.

- The East: The obsession with the East (east-facing horse heads, eastern placement of altars) ties the culture undeniably to the Sun. The daily rebirth of the sun was likely linked to the rebirth of the ancestors or the continuity of the lineage.

Some researchers believe the layout of the Khirgisuurs mirrors the surrounding mountain peaks, grounding the stone structure into the "living" geography of the valley.

8. The Great Transition: From Khirgisuur to Slab Grave

Around 700 BCE, the Khirgisuur culture began to fade. It was replaced by the Slab Grave Culture, the direct ancestors of the Xiongnu (the first Mongol Empire).

This transition was not always peaceful. In many sites, archaeologists find evidence of desecration.

- Repurposing: The Slab Grave people often dismantled the beautiful Deer Stones, chopping them up to use as building blocks for their own rectangular graves.

- A New Order: The end of the Khirgisuur era marked a shift in society. The massive, labor-intensive communal monuments disappeared, replaced by smaller, individual graves. This might signal a change in how power was held—moving from a ritual-based power (building monuments) to a military-based power (mounting armies) that would eventually lead to the great steppe empires.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy

The Khirgisuur monuments of Mongolia are more than just piles of rocks. They are the fingerprints of a lost civilization that mastered the harsh steppe through ingenuity, community, and the horse. They stand as a testament to a time when people did not build cities of wood and brick, but rather imprinted their beliefs directly onto the face of the earth with stone.

Today, as you stand in the shadow of a Khirgisuur in the Khanui Valley, watching the sun rise over the same mountains that these ancient herders worshipped, you are witnessing a continuity of spirit that has lasted three thousand years. The horses are gone, the fires are out, but the stones remain—silent, imposing, and eternal.

Visitor's Guide: How to See Khirgisuurs

If you are planning a trip to Mongolia to see these wonders:

Reference:

- https://arkeonews.net/geological-surveys-in-mongolia-uncover-3000-year-old-nomadic-khirgisuur-burial-mounds/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237950705_Organizational_Principles_of_Khirigsuur_Monuments_in_the_Lower_Egiin_Gol_Valley_Mongolia

- https://seaa-web.org/content/archaeological-geophysical-and-geochemical-approaches-investigating-late-bronze-age

- https://repository.si.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/62c880a2-ca22-40b9-be96-43aa35d2a606/content

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288455689_Khirigsuurs_ritual_and_mobility_in_the_Bronze_Age_of_Mongolia

- https://www.maajournal.com/index.php/maa/article/download/889/802/1558

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288953699_Bronze_Age_burial_mounds_Khirigsuurs_in_the_Hovsgol_aimag_Mongolia_a_reconstruction_of_biological_and_social_histories

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/abs/earliest-bronze-age-culture-of-the-southeastern-gobi-desert-mongolia/67B30B43A0D6CE444A0BE0F3736F8713

- https://sucra.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/2000820/files/GD0001673.pdf

- https://www.pivotscipub.com/hpgg/4/1/0004/html

- https://www.anthropology-news.org/articles/herding-heritage/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7664836/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8011967/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khirigsuur

- https://brill.com/display/book/9789004541306/BP000015.xml?language=en

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Differences-in-the-appearance-of-slab-burial-stelae-in-Mongolia-1-Ar-Bulan-Bronze_fig12_321917767

- https://brill.com/display/book/9789004541306/BP000015.xml

- https://grokipedia.com/page/Slab-grave_culture