In the vast, silent theater of the prehistoric world, bones tell us what our ancestors looked like, but footprints tell us who they were. For decades, the study of human evolution was a puzzle pieced together from fragments of skulls and femurs—static snapshots of death. But a footprint is a record of life. It captures a breath, a stride, a fleeting moment of interaction that occurred millions of years ago and was then locked in stone.

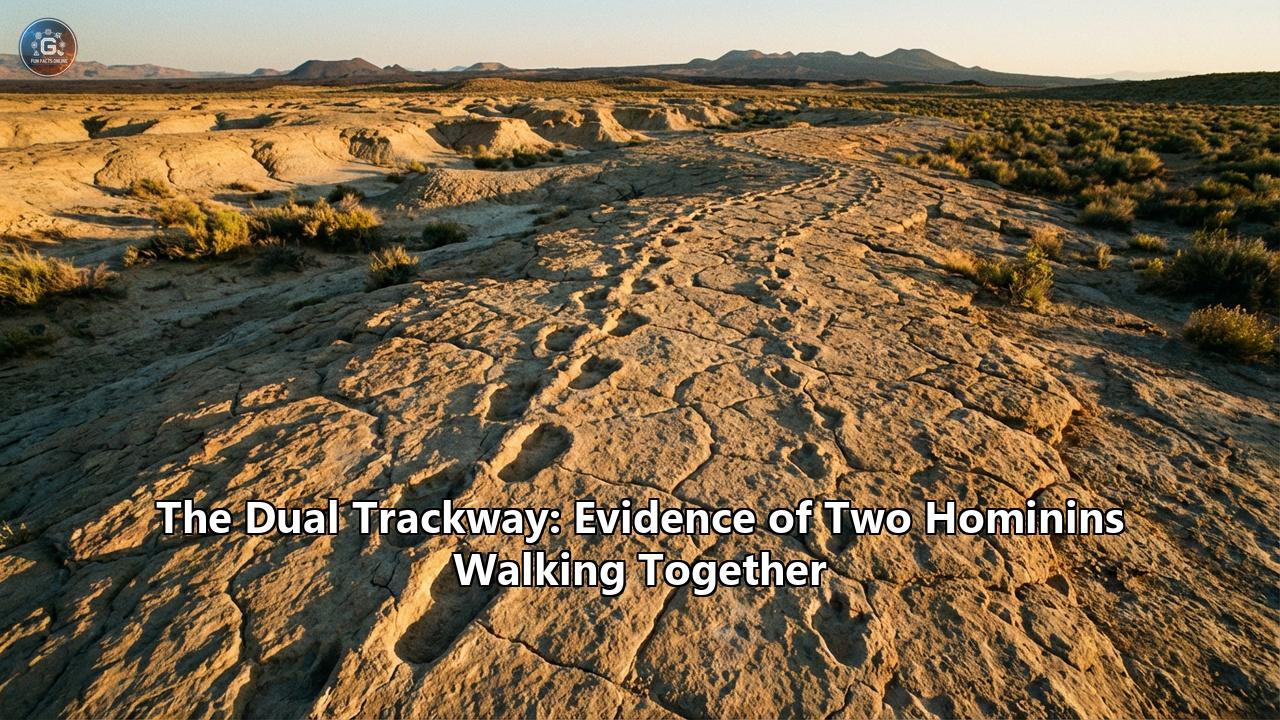

Among these trace fossils, few discoveries have ignited the imagination of the scientific community and the public alike as powerfully as the phenomenon of the "Dual Trackway." While the term has historically evoked the famous image of two Australopithecines walking through volcanic ash at Laetoli, a groundbreaking discovery in the Turkana Basin of Kenya has recently redefined it. We now have evidence not just of two individuals walking together, but of two entirely different species of ancient hominins—Homo erectus and Paranthropus boisei—crossing paths on the same lakeshore, within hours of each other.

This is the story of those trackways. It is a story that bridges the gap between 3.7 million years ago and 1.5 million years ago, revealing the social bonds, the diverse walking styles, and the surprising coexistence of our ancestors.

Part I: The Miracle of the Turkana Basin

The Discovery that Rewrote the Timeline

For over a century, the concept of human evolution was often depicted as a linear march—the "March of Progress"—where a primitive ape slowly stood up, became a knuckle-walker, and eventually straightened into a modern human. We now know this is a myth. The family tree is messy, bushy, and tangled. The most striking evidence of this tangle was unearthed on the eastern shores of Lake Turkana in Kenya, a region often called the "Cradle of Mankind."

In late 2024, a team of paleontologists unveiled a discovery that sent shockwaves through the anthropological world. Buried beneath layers of sediment dating back 1.5 million years, they found a single, preserved mud surface containing two distinct sets of footprints.

One set was unmistakable: the long, striding gait of Homo erectus, the direct ancestor of modern humans. The prints showed an arched foot, a non-divergent big toe, and a heel-strike pattern identical to our own. These were the walkers, the travelers, the species that would eventually leave Africa to populate the globe.

But crisscrossing these tracks, on the very same layer of mud, was a second set of prints. These were different. They were flatter, with a distinct weight distribution that suggested a creature built for stability rather than speed. These prints belonged to Paranthropus boisei—the "Nutcracker Man."

A Meeting in the Mud

The significance of this "Dual Trackway" cannot be overstated. For years, fossil hunters had found bones of both species in the same geological layers. We knew they lived in the same era. But time in geology is deep; two fossils found in the same layer could still be separated by ten thousand years.

The footprints changed everything. Trace fossils are ephemeral. A footprint in mud lasts only a few hours or days before it is washed away by rain or covered by wind. For these two sets of tracks to exist on the same preserved surface, these two different species must have walked across that beach within hours of each other.

They breathed the same air. They heard the same birds calls. They likely saw each other.

This discovery shattered the idea that our ancestors lived in isolation. Instead, it painted a picture of a crowded Pleistocene landscape where different experiments in being "human" were playing out simultaneously. The "Dual Trackway" of Turkana is the first direct behavioral evidence of an inter-species neighborhood.

Part II: The Players on the Stage

To understand the weight of these footprints, we must understand the walkers.

Homo erectus: The Endurance Walker

The tracks assigned to Homo erectus reveal a creature that had mastered the art of bipedalism. By 1.5 million years ago, H. erectus had evolved a body plan strikingly similar to ours. They had long legs, shorter arms, and a barrel-shaped ribcage.

- The Gait: The footprints show a strong "longitudinal arch"—the spring in the foot that absorbs shock and recycles energy. This is the hallmark of an endurance walker. H. erectus was not just walking; they were patrolling. They were hunters and gatherers who covered vast distances under the African sun.

- The Mind: This was a species with a growing brain (approx. 900cc), capable of making sophisticated stone tools (the Acheulean handaxes) and possibly controlling fire. Their tracks in the Turkana mud are purposeful, moving in straight lines, suggesting a destination.

Paranthropus boisei: The Specialist

Walking the same path was Paranthropus boisei, a creature that represents a completely different evolutionary strategy.

- The Anatomy: P. boisei was a robust hominin. They had massive jaws and molar teeth four times the size of a modern human’s, anchored by a sagittal crest (a bony ridge on top of the skull) that supported powerful chewing muscles.

- The Gait: The footprints attributed to P. boisei show a flatter foot and a slightly different stride mechanics. They were fully bipedal—they didn't walk on their knuckles—but they were likely less efficient at long-distance travel than H. erectus. They were the "cows" of the hominin world, specialized feeders who spent their days grazing on sedges, grasses, and hard nuts near the waterways.

The Coexistence Mystery

How did two upright-walking primates share the same habitat without driving each other to extinction? The answer lies in "Niche Partitioning." The Dual Trackway confirms that while they shared the space, they did not compete for the resources. Homo erectus was likely chasing game and gathering high-energy foods, while Paranthropus boisei was munching on the tough, fibrous vegetation that Erectus couldn't eat. They were neighbors, perhaps indifferent to one another, passing like ships in the Pleistocene night.

Part III: The Original Dual Trackway — Laetoli

While the Turkana discovery is the new face of the "Dual Trackway" phenomenon, it stands on the shoulders of the most famous footprint site in the world: Laetoli, Tanzania. Discovered in 1978 by Mary Leakey’s team, the Laetoli footprints are much older—3.66 million years old—and tell a different, more intimate story.

Site G: The First Family?

At Laetoli, a volcanic eruption blanketed the landscape in ash, which then turned to cement-like mud after a rainstorm. Walking across this wet ash were three individuals of the species Australopithecus afarensis (the same species as "Lucy").

The most famous trackway, Site G, shows two parallel lines of footprints.

- The Larger Tracks: One set of prints belongs to a larger individual (likely male).

- The Smaller Tracks: Running alongside is a set of smaller prints (likely female).

- The Third Walker: Within the larger footprints, there is often a "double impression," leading some scientists to believe a third, smaller individual was walking in the footsteps of the larger one—a behavior often seen in children mimicking parents.

For decades, this "Dual Trackway" was the romanticized icon of human evolution. It suggested pair-bonding, nuclear families, and social cohesion. It showed us that 3.7 million years ago, long before big brains or stone tools, we were already walking side-by-side.

Site S: The Giant

In 2016, a new set of footprints was discovered nearby at "Site S." These prints were massive, belonging to an A. afarensis individual standing nearly 5 feet 5 inches tall—huge for that era. This added a new dimension to the Laetoli dual trackway concept: sexual dimorphism. The vast size difference between the Site S individual and the Site G individuals suggested that A. afarensis males were much larger than females, implying a social structure more like gorillas (harems) than modern humans (monogamous pairs).

Part IV: The Science of Reading the Mud

How do scientists extract so much information from a depression in the ground? The science is called Ichnology, and it has undergone a digital revolution.

1. Photogrammetry and 3D Scanning

In the days of Mary Leakey, footprints were cast in plaster. Today, scientists use laser scanning and photogrammetry to create microscopic 3D topographic maps of the ground.

- Depth Analysis: By measuring the depth of the toe impression vs. the heel impression, scientists can calculate the speed of the walker. A deeper toe print usually indicates running or forceful walking.

- Pressure Pads: The distribution of sediment displacement reveals the foot's arch. A human foot acts like a lever: Heel strike -> Roll along the outer edge -> Pronation (rolling in) -> Toe-off. The Turkana and Laetoli prints show this "human" biomechanical pattern, distinguishing them from the flat-footed shuffle of chimpanzees.

2. The "Substrate" Variable

One of the challenges in analyzing the Dual Trackway is the mud itself. Was it slippery? Was it deep?

- In Laetoli, the ash was wet and cohesive, capturing incredible detail, even the texture of the skin in some cases.

- In Turkana, the substrate was often lake margin mud. The P. boisei prints, being flatter, might partially be a result of the mud's consistency, but comparative analysis with the H. erectus prints on the same mud proves the difference is anatomical, not environmental.

Part V: Social Lives and Group Behavior

The "Dual" aspect of these trackways—whether two species in Turkana or two individuals in Laetoli—opens a window into the mind of early hominins.

The Ileret Hunting Parties

Beyond the famous dual tracks, another site at Ileret (dating to 1.5 Ma) revealed something even more startling: a cluster of footprints moving in the same direction. Analysis showed these were all made by adult males of Homo erectus.

This wasn't a family stroll; it was a squad.

In modern hunter-gatherer societies and in chimpanzees, groups of males patrol boundaries or hunt cooperatively. The Ileret tracks provided the first evidence of male cooperation in Homo erectus. This suggests that by 1.5 million years ago, we had already developed the complex social structures necessary for group hunting and perhaps warfare.

The Emotional Connection

Why do we find the image of two hominins walking together so moving? Because bipedalism is a vulnerable way to move. It is slow and unstable compared to four-legged movement. To walk upright is to expose the soft underbelly. To walk upright together implies trust.

The Laetoli tracks show individuals walking close enough to touch. Whether they were holding hands (as artistic reconstructions often show) is speculation, but their proximity is a fact. They were aware of each other. They were a unit.

Part VI: The Preservation Paradox

The existence of these footprints is a statistical impossibility. For a footprint to become a fossil, a specific sequence of events must occur:

- The Impression: The individual must walk on a surface that is soft enough to mold but firm enough to hold shape (like damp volcanic ash or drying mud).

- The Baking: The sun must bake the print dry and hard before the next tide or rain washes it away.

- The Burial: A gentle layer of sediment (sand or new ash) must cover the print without eroding it.

- The Lithification: Millions of years of pressure must turn the sediment into rock.

- The Erosion: Modern weather must erode the top layers just enough to expose the prints, but not so much that they are destroyed before a scientist walks by.

The Turkana Dual Trackway is even more miraculous because it captured two species. It suggests that these lake margins were "hominin highways"—busy corridors where food and water attracted everyone.

Part VII: Conclusion — The Walk Continues

The "Dual Trackway" is more than just a geological curiosity. It is a mirror.

When we look at the tracks of Homo erectus and Paranthropus boisei intersecting in the Kenyan mud, we are looking at the moment our lineage decided its future. One species—the specialist chewer—would eventually walk into the dead end of extinction. The other—the generalist walker—would walk out of Africa and into the future.

But for that one afternoon, 1.5 million years ago, they were just two creatures trying to survive on the edge of a lake. They may have glanced at each other with suspicion or indifference, unaware that their footprints would one day be uncovered by their distant descendants, seeking to understand the long, lonely walk that led to us.

These trackways remind us that we were never truly alone. Our history is one of coexistence, of side-by-side struggles, and of the enduring mark we leave on the world—one step at a time.

Reference:

- https://www.earth.com/news/hominin-footprints-show-two-extinct-species-of-early-humans-lived-side-by-side/

- https://newatlas.com/biology/fossil-footprints-two-hominin-species-same-day/

- https://www.iflscience.com/15-million-year-old-footprints-suggest-two-ancient-human-relatives-walked-together-76996

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Oz0tG9ku1jQ

- https://scitechdaily.com/1-5-million-year-old-tracks-reveal-unexpected-coexistence-of-two-human-ancestors/

- https://nutcrackerman.com/2016/12/14/quick-summary-of-the-new-hominin-footprints-at-laetoli/

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/footprints-reveal-two-early-human-species-walked-the-same-lakeshore-in-kenya-15-million-years-ago-180985561/

- https://mymodernmet.com/laetoli-hominid-footprints/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/383180254_Ileret_Footprints

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laetoli

- https://www.johnhawks.net/p/new-footprints-from-laetoli