The Roman earth beneath London has spoken again, and its voice is louder than ever.

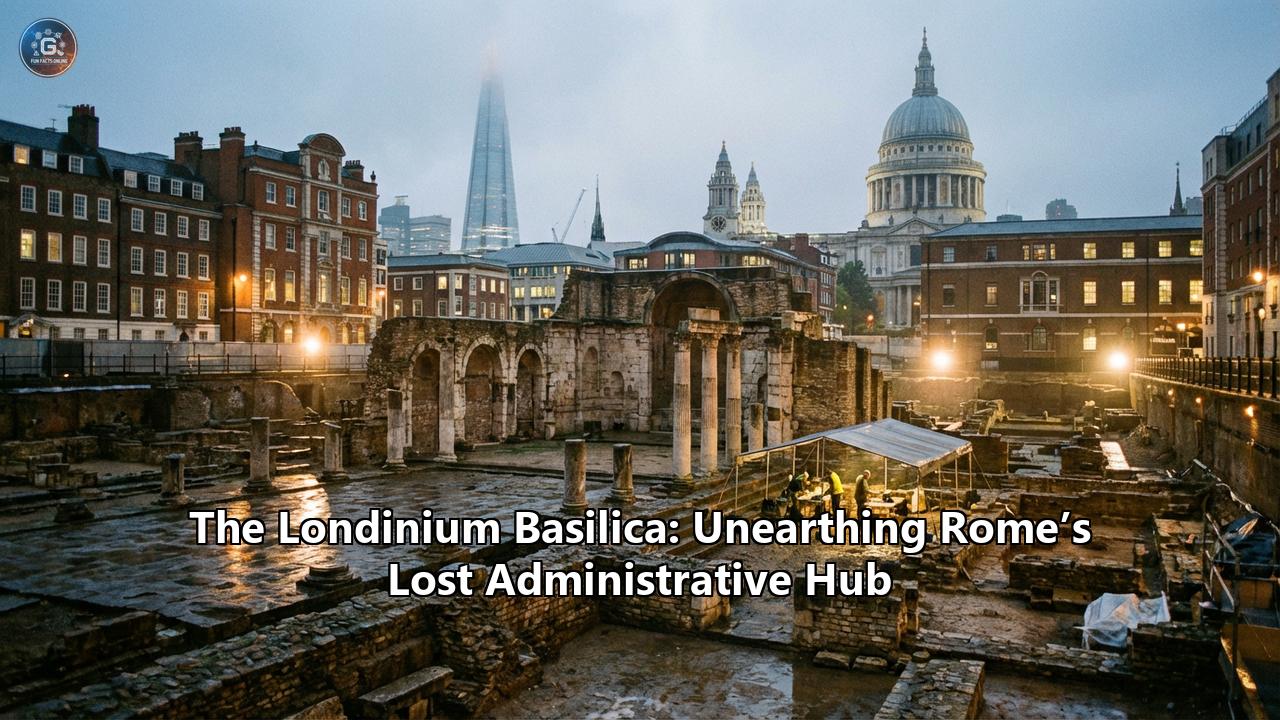

In February 2025, archaeologists excavating beneath the concrete roots of a 1980s office block at 85 Gracechurch Street struck history. They didn’t just find a wall; they found the tribunal—the raised platform where Roman governors and magistrates once sat to pass judgment, issue edicts, and shape the destiny of the province of Britannia. This discovery has thrown a spotlight back onto one of the ancient world’s most impressive, yet ghostly, structures: the Londinium Basilica.

Once the largest building north of the Alps, bigger than the present-day St Paul’s Cathedral, this administrative behemoth was the beating heart of Roman London. It was a cathedral of commerce, a palace of justice, and the engine room of imperial power. And then, it vanished.

This is the comprehensive story of the Londinium Basilica—its rise, its glory, its mysterious destruction, and its miraculous rediscovery.

Part I: The Accidental Capital

To understand the Basilica, one must first understand the city it served. Unlike other Roman towns in Britain—such as Camulodunum (Colchester) or Verulamium (St Albans)—Londinium was not a pre-existing Celtic tribal capital. It was a new town, a startup city founded by Rome around AD 47-50.

The Strategic Crossing

The Romans needed a bridge. The Thames was a formidable barrier, wide and tidal. Their engineers found a spot where two gravel hills (now Cornhill and Ludgate Hill) rose from the marshy banks, narrowing the river enough to span it. They built a bridge, and around its northern bridgehead, a settlement exploded into life.

This was Londinium. It was a logistical hub, a supply depot, and a port. Traders, soldiers, opportunistic merchants, and bureaucrats flocked here. It was a chaotic, muddy boomtown—a "Wild West" on the edge of the known world.

Boudica’s Fire

In AD 60, just over a decade after its founding, the city was wiped off the map. Queen Boudica of the Iceni, enraged by Roman brutality, led a revolt that burned Londinium to the ground. The archaeological layer of red, burnt clay—the "Boudican destruction horizon"—is still found under London today.

But Rome did not abandon its bridgehead. They rebuilt, and this time, they decided to make a statement. They would not just build a town; they would build a capital. And a capital needed a heart.

Part II: The First Basilica (The Agricolan Phase)

The recent 2025 discovery at Gracechurch Street has given us our best look yet at this first attempt to monumentalize London.

Built around AD 70-80, likely under the governorship of Gnaeus Julius Agricola (the man who would later attempt to conquer Scotland), the first basilica was a statement of intent.

The Design

It was modest compared to what came later, but massive for the time. It was a rectangular hall, constructed of timber and masonry, facing onto a public square (the forum).

- Location: It sat on the summit of the eastern hill (Cornhill), the highest point in the city.

- Function: It combined the roles of a town hall, a law court, and a covered market.

- The Discovery: The 2025 dig revealed walls up to 3 meters thick. The preservation was "extraordinary," with archaeologists uncovering the tribunal—the high seat of power. Standing there, you are standing on the very spot where the governor would have addressed the city’s elite.

This building signaled that Londinium was no longer just a port; it was becoming a Municipium or perhaps a Colonia, a city with self-governing rights and the dignity of Rome.

Part III: The Great Basilica (The Hadrianic Complex)

By AD 90, London was booming. The population had swelled to perhaps 30,000 or even 60,000 people. The first basilica was too small. The city planners, flush with imperial cash and ambition, decided to demolish it and build something the likes of which Britain had never seen.

They built a monster.

The "Monster" of Cornhill

Construction of the second basilica began around AD 90 and continued for decades, finishing around AD 120 (just in time for Emperor Hadrian's visit in AD 122).

- Scale: The complex was vast. The basilica itself was over 500 feet (150+ meters) long. The nave (the central hall) was as wide as the nave of St Paul’s Cathedral and rose three stories high.

- The Complex: It wasn’t just a building; it was a complex.

The Forum: To the south lay a massive open-air piazza, surrounded by colonnades and shops (tabernae). This was the marketplace, the social hub, the "Trafalgar Square" of Roman London.

The Basilica: To the north, closing off the square, stood the basilica itself. It acted as the "backstop" to the forum.

- Architecture: It was built of Kentish ragstone, imported from quarries near Maidstone, with bonding courses of red brick. The interior was clad in marble veneers imported from the Mediterranean—green porphyry from Greece, white Carrara from Italy. The floors were paved with opus signinum (crushed tile concrete) or mosaics.

Inside the Great Hall

Imagine walking into the Great Basilica in AD 125.

You enter from the bustling, noisy Forum, stepping through massive portico doors. The noise of the market fades slightly, replaced by a cavernous echo.

- The Aisles: To your left and right are double rows of towering stone columns, creating aisles where merchants set up stalls, moneylenders (argentarii) count coins, and lawyers argue with clients.

- The Nave: The central space is open, lit by clerestory windows high above. It is smoky from oil lamps and braziers.

- The Offices: Along the northern wall is a row of offices. These are the bureaucratic engine rooms. Here, clerks update the census, tax collectors track grain shipments, and scribes draft letters to Rome.

- The Tribunal: At the eastern end, on a raised dais within an apse, sits the Governor of Britannia. He is surrounded by lictors (bodyguards) and advisors. He is hearing a capital case. The fate of a man—citizenship, slavery, or death—is being decided in Latin, the language of power.

This building was the physical manifestation of the Pax Romana. It said to every Briton: "Rome is big, Rome is permanent, and Rome is here to stay."

Part IV: Voices from the Mud (The Bloomberg Tablets)

Buildings are just stone; it is people who make a city. While the Basilica has left us its foundations, the people who worked there have left us their voices—preserved in mud.

Excavations near the Walbrook river (the Bloomberg site) recovered hundreds of wooden writing tablets. These were the emails of the Roman world—stylus-scratched notes on wax-covered wood. They give us a direct line to the business conducted in and around the Basilica.

- The First "Londoner": One tablet, dated AD 65-80, contains the address "Londinio Mogontio" ("In London, to Mogontius"). It is the earliest written reference to the city’s name.

- Debts and Deals: We read of Tibullus the freedman, who promises to pay a debt. We see contracts for "20 loads of provisions" sent from St Albans to London.

- The Judge: One tablet mentions a "pre-trial hearing." This would have happened right here, in the Basilica.

- Education: We find the alphabet scratched out by a child—evidence of a school, perhaps held in the porticoes of the forum.

These tablets reveal a city of hustlers, immigrants, soldiers, and slaves. A city where a man from Athens could trade with a man from Gaul, using a currency minted in Rome, under laws enforced in the Londinium Basilica.

Part V: The Mystery of the "Hadrianic Fire"

Just as the Great Basilica reached its peak, disaster struck. Around AD 125-130, a massive fire ripped through London.

Archaeologists call it the "Hadrianic Fire." Unlike the Boudican fire, there is no historical record of a war or revolt.

- The Damage: The fire was so intense it melted glass and baked the clay walls of buildings into red brick. The Basilica was heavily damaged.

- The Theories:

Accidental? London was a fire trap of timber and thatch. A overturned lamp could have done it.

Rebellion? Some historians speculate about a "Hadrianic War"—an unrecorded revolt that required the Emperor’s personal presence in Britain to suppress. Was the fire an act of war?

Clearance? Or was it a slum clearance gone wrong?

Whatever the cause, the city—and the Basilica—rebuilt. But the golden age was fading.

Part VI: The Carausian Revolt and the Final Fall

The story of the Basilica’s destruction is as dramatic as its construction. It did not just rot away; it was erased.

By the late 3rd Century, the Roman Empire was fracturing. In AD 286, a Roman naval commander named Carausius seized power in Britain. He declared himself Emperor of the North, minting coins in London that proclaimed a new "British Empire" separate from Rome.

For seven years, London was the capital of this breakaway empire. The Basilica would have been Carausius’s showpiece—the center of his rogue court.

But the Empire struck back. In AD 296, the legitimate Emperor Constantius Chlorus invaded. Carausius was assassinated by his own treasurer, Allectus, and Allectus was then defeated by Rome. London was retaken.

The Punishment:Rome did not forgive traitors. Following the reconquest, it appears that the Great Basilica was systematically demolished.

- The Evidence: Around AD 300, the site of the basilica was leveled. The great masonry walls were dismantled. The stone was not just stolen; the building was removed.

- The Reason: This wasn't just recycling. It was likely a damnatio memoriae—a punishment of the city. London was stripped of its status. The administrative center was broken up, and the province was divided into four smaller units to prevent any one governor from becoming too powerful again.

The great civic heart of London was turned into a workshop area. The grand forum became a place for small industrial fires and dust. The "Cathedral of Rome" was gone.

Part VII: The Rediscovery

For 1,500 years, the Basilica slept. Saxon Lundenwic grew to the west (near Covent Garden), and when the walled city was reoccupied in the 9th century, the new medieval streets of Gracechurch and Cornhill were laid out right over the top of the Roman ruins, completely oblivious to them.

The ghost of the Basilica began to emerge in the Victorian era.

The Victorian Market (1880s)

In 1881, workers digging the foundations for the ornate Leadenhall Market (which still stands today) hit massive walls. They found arches and piers of incredible strength. At the time, they didn't fully understand the plan, but they knew they had found the Roman center.

- The Barber Shop Secret: Today, if you visit Nicholson & Griffin, a barber shop in the corner of Leadenhall Market, you can ask to go to the basement. There, between the hair products and towels, is a preserved arch of the Roman Basilica. It is one of London’s greatest hidden secrets.

The 20th Century Detectives

In the post-WWII era, archaeologists like Peter Marsden and Brian Philp began to piece the jigsaw together. As bombsites were cleared and skyscrapers rose, they mapped the walls. They realized that the "bits and pieces" found over 100 years were all part of one colossal structure.

The 2025 Breakthrough

Which brings us back to 85 Gracechurch Street. The 2025 excavation was the final piece of the puzzle. It confirmed the location of the eastern tribunal and provided the high-definition detail—the painted plaster, the specific floor levels—that the Victorians missed.

Conclusion: The Shadow of Rome

The Londinium Basilica is a reminder of how deep the roots of London go.

When you walk down Gracechurch Street today, you are walking down the nave of a ghost building.

When you enter Leadenhall Market to buy a coffee, you are standing in the middle of the Roman Forum, where a soldier from Syria might have bought oysters from a trader from Kent 1,900 years ago.

The Basilica was a symbol of an empire that believed it would last forever. It didn’t. But in its ruins, we find the DNA of London: a city of trade, of law, of diverse voices, and of constant, ruthless reinvention.

The 2025 discovery is not just about rocks; it’s about reconnecting with the first time London decided to be a World City.

Visitor’s Guide: Tracing the Basilica Today

While the Great Basilica is gone, you can still touch its ghost:

- The Leadenhall Barber Shop: Visit Nicholson & Griffin* in Leadenhall Market. Ask politely to see the Roman wall in the basement.

- The London Wall: Walk to nearby Tower Hill to see the defensive wall that was built using recycled stones—some likely from the demolished Basilica.

- The Museum of London: View the frescoes and mosaics recovered from the Cornhill area.

- The Future Display: The developers of the 85 Gracechurch Street tower have promised to create a public viewing gallery for the newly discovered Tribunal remains. Watch this space in 2026-27.

Reference:

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/archaeologists-unearth-the-ruins-of-a-2000-year-old-roman-basilica-beneath-an-office-building-in-london-180986070/

- https://apnews.com/article/london-roman-basilica-archaeology-londinium-forum-tribunal-38df5698485f50bfc00c487b1fb246ec

- https://www.mola.org.uk/discoveries/news/uncovering-heart-roman-london

- https://www.layersoflondon.org/map/records/reconstructing-the-forum-and-basilica-of-roman-london/gallery/3

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Paul%27s_Cathedral

- https://london.fandom.com/wiki/Londinium

- https://editions.covecollective.org/chronologies/roman-londons-forum-and-basilica

- https://www.mylondon.news/news/nostalgia/london-roman-ruin-tube-station-19976245

- https://coalholesoflondon.wordpress.com/2018/06/11/londons-roman-basilica-and-forum/

- https://londonist.com/london/history/londinium-basilica-visitor-centre

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Roman_architecture

- https://imperiumromanum.pl/en/article/basilicas-first-significant-churches-of-ancient-romans/

- https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryMagazine/DestinationsUK/Londons-Roman-Basilica-Forum/

- https://time.com/4354606/london-archaeology-tablet-wax-writing/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bloomberg_tablets

- https://www.bajr.org/roman-london-lives-with-publication-of-80-writing-tablets/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TCInpr0cOmQ

- https://locallondoner.home.blog/2019/03/19/the-leadenhall-barbers-with-a-secret-down-below/

- https://news.artnet.com/art-world/roman-basilica-london-found-2608421