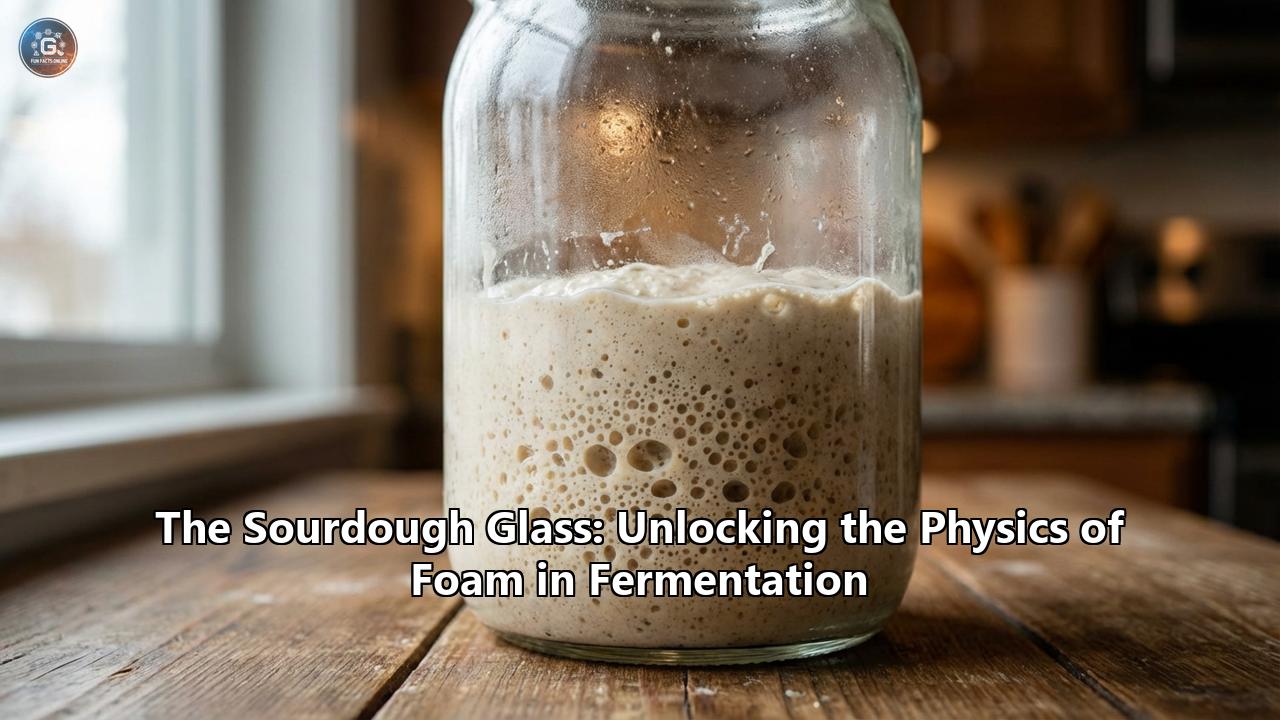

The world of sourdough is often painted in the soft, warm hues of nostalgia—a rustic tradition passed down through grandmothers, a tactile art form defined by intuition and "feeling" the dough. But peer closer, through the transparent wall of a fermentation jar, and you will find a universe governed not by magic, but by the rigorous, elegant, and often violent laws of soft matter physics. To the baker, it is a loaf; to the physicist, it is a complex, non-equilibrium foam stabilizing a biological runaway reaction.

This is the story of The Sourdough Glass. It is a triple entendre: the glass jar that allows us to witness the birth of the foam, the "glassy state" of the shattering crust that encases the finished loaf, and the metaphorical magnifying glass we must hold up to understand the invisible forces at play. From the moment flour meets water to the final crackling song of the cooling loaf, we are witnessing a masterclass in rheology, thermodynamics, and polymer science.

This comprehensive exploration will dissect the physics of the sourdough foam, unlocking the molecular secrets that separate a dense brick from an airy, open-crumb masterpiece.

Part I: The Genesis of the Foam (Mixing and Nucleation)

The life of a sourdough loaf begins with a paradox: yeast cannot create bubbles.

It is a common misconception that the carbon dioxide ($CO_2$) produced by fermentation blows up the balloon of the dough from scratch. In reality, $CO_2$ is unable to overcome the surface tension of the dough’s aqueous phase to form a new bubble spontaneously. The pressure required to nucleate a gas bubble de novo in a liquid is astronomically high—far beyond the capabilities of a single yeast cell.

Instead, the bubbles that will eventually become the alveoli (the holes in your crumb) are born during mixing. This is the Nucleation Phase.

1.1 The occlusion of Air

When flour and water are combined and agitated—whether by hand or a spiral mixer—atmospheric air is folded into the sticky mass. These microscopic pockets of air, primarily nitrogen ($N_2$) and oxygen ($O_2$), are trapped within the developing gluten matrix. They are the "seeds" of the loaf. Without them, the yeast would produce $CO_2$ that would simply dissolve into the water and eventually diffuse out of the dough, leaving you with a flat, dense puck.

The physics of mixing is thus a race against time to occlude as many microscopic nucleation sites as possible. The structure of the final crumb is determined here. A high-speed mix creates a proliferation of tiny, uniform bubbles (resulting in a sandwich bread texture), while a gentle hand-mix or slow fold preserves fewer, larger, irregular bubbles (the chaotic beauty of an artisan loaf).

1.2 Hydration and the Water Dipole

Before the foam can stabilize, the stage must be built. This is the realm of Hydration Physics. Water is not merely a solvent; it is a plasticizer. Wheat flour contains two key proteins: gliadin and glutenin. In their dry state, they are inert, tightly coiled, and glassy.

When water is introduced, its polar molecules (dipoles) insert themselves between the protein chains. This lowers the glass transition temperature ($T_g$) of the proteins, transforming them from a rigid solid into a pliable, cohesive system. The gliadins (monomeric) act as a viscous solvent, providing fluidity, while the glutenins (polymeric) link up via disulfide bonds to form a vast, elastic network.

This network is the "walls" of our foam. In a high-hydration sourdough (80% water content or more), the physics shifts dramatically. The dough behaves less like a solid and more like a non-Newtonian fluid. The abundance of water increases the mobility of the polymers, allowing for greater extensibility, but it also dilutes the gluten network, making gas retention more precarious. The baker must balance the lubrication required for expansion against the structural integrity needed to hold the foam together.

Part II: The Biological Engine (Fermentation Dynamics)

Once the mixing stops, the biological engine—the sourdough starter—roars to life. A sourdough culture is a symbiotic ecosystem of wild yeasts (often Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Candida humilis) and lactic acid bacteria (LAB, such as Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis).

2.1 Diffusion and Inflation

As fermentation begins, the yeast metabolizes simple sugars and produces $CO_2$ and ethanol. The $CO_2$ enters the aqueous phase of the dough (the water trapped in the gluten network).

Here, Henry’s Law takes effect. The water becomes saturated with $CO_2$. Because it cannot form new bubbles, the gas seeks the path of least resistance: the pre-existing air bubbles created during mixing. Driven by concentration gradients, $CO_2$ diffuses from the liquid dough into these nitrogen gas nuclei.

The bubble expands. The dough rises.

2.2 The Acid Effect on Rheology

The LAB are not idle. They produce lactic acid and acetic acid, lowering the pH of the dough from a neutral 6.0 to a tart 3.5–4.0. This acidification is not just about flavor; it alters the physics of the foam.

Gluten proteins are sensitive to pH. As the environment becomes more acidic, the net positive charge on the protein chains increases. This leads to electrostatic repulsion between the chains—they push away from each other. This "unfolding" effect softens the gluten, making it more extensible (stretchy). However, too much acid (over-fermentation) can degrade the gluten completely, turning the dough into a proteolytic soup that cannot hold gas. The "Sourdough Glass"—the jar we watch—is a monitor of this delicate balance between expansion and degradation.

Part III: The Physics of Foam Stability

Why doesn't the foam collapse? A bowl of soap bubbles pops in minutes; a sourdough loaf must hold its structure for hours, sometimes days. The stability of sourdough foam relies on two distinct physical mechanisms.

3.1 The Viscoelastic Matrix (Primary Stabilization)

In the early stages of fermentation, the bubbles are spherical and separated by thick walls of dough. The stability here is provided by the Viscoelasticity of the gluten-starch matrix.

- Viscosity (Liquid-like behavior) allows the dough to flow and expand as the gas pressure increases.

- Elasticity (Solid-like behavior) provides the restoring force that prevents the bubble from bursting.

The key property here is Strain Hardening. As the bubble wall stretches, the gluten polymer chains uncoil. Once they are fully extended, they resist further stretching, causing the material to "harden" or become stiffer. This is crucial. If a thin spot develops in the bubble wall, strain hardening ensures that this spot becomes stronger than the surrounding thick areas, preventing rupture. It is a self-healing mechanism built into the chemistry of wheat.

3.2 The Liquid Lamellae (Secondary Stabilization)

As the dough expands further, the walls between bubbles become microscopically thin. The starch granules—large, rigid boulders compared to the gluten strands—can disrupt the network. The gluten film may actually rupture.

Why does the gas not escape? Recent research points to a "Secondary Stabilization" mechanism: Liquid Lamellae. A thin film of liquid, stabilized by surface-active agents (polar lipids and soluble proteins present in the flour), forms a bridge across the gaps in the gluten network. This is identical to the physics of a soap bubble. These surfactants lower the surface tension at the gas-liquid interface, preventing the film from draining and collapsing.

3.3 Disproportionation (Ostwald Ripening)

Looking through the glass of your fermentation jar, you might notice that large bubbles seem to "eat" the smaller ones. This is Ostwald Ripening, driven by Laplace Pressure.

The pressure ($P$) inside a bubble is inversely proportional to its radius ($R$), described by the Young-Laplace equation:

$$ \Delta P = \frac{2\gamma}{R} $$

Where $\gamma$ is surface tension.

Smaller bubbles have higher internal pressure than larger bubbles. Consequently, gas diffuses from the high-pressure small bubbles into the low-pressure large bubbles. The small bubbles shrink and vanish; the large bubbles grow. In sourdough, this creates the characteristic "wild crumb"—an irregular landscape of massive caverns and tiny alveoli, contrasting with the uniform crumb of commercial yeast bread where fast proofing limits this physical migration.

Part IV: The Alimentary Glass (The Aliquot Method)

In modern sourdough physics, the "Sourdough Glass" has become a literal tool: the Aliquot Jar.

Bakers pinch off a small piece of dough and place it in a small, straight-sided cylinder (a test tube or spice jar) to monitor expansion.

This creates a controlled physical system to measure Volume Expansion ($\Delta V$).

The physicist baker knows that time is a poor metric for fermentation because it is dependent on temperature (Arrhenius equation). A dough at $21^{\circ}\text{C}$ ferments half as fast as one at $27^{\circ}\text{C}$. By observing the aliquot jar, the baker measures the result of the kinetics (gas production) rather than the input (time).

When the dough in the glass increases by 30% to 50% (depending on flour strength), the foam is at its limit of stability. The gluten network is maximally extended but hasn't yet reached the fracture point. This is the moment of "baking."

Part V: Thermodynamics of the Oven Spring

The transition from "foam" to "sponge" occurs in the oven. This is a violent, chaotic event known as Oven Spring.

5.1 The Gas Laws in Action

As the cold dough hits the hot stone (often $250^{\circ}\text{C}$), heat transfer begins. The crust heats rapidly, but the center lags behind.

Three physical forces drive the sudden expansion:

- Thermal Expansion (Charles's Law): As the temperature of the gas inside the bubbles rises, the volume increases ($V \propto T$).

- Solubility Drop: Gases are less soluble in hot liquids. The $CO_2$ dissolved in the dough's water is suddenly forced out of solution, rushing into the bubbles.

- Evaporation: Water and ethanol flash into steam. Since water expands roughly 1,600 times when converting to steam, this provides a massive kick of pressure.

5.2 The Gelatinization Threshold

At roughly $60^{\circ}\text{C}$ to $80^{\circ}\text{C}$, the starch granules begin to absorb water greedily and swell, a process called Gelatinization. They lose their crystalline structure and become an amorphous gel.

Simultaneously, the gluten proteins Denature. They unravel and cross-link, coagulating into a rigid structure.

This is the critical "setting" of the foam. If the gas pressure expands the bubbles before the starch sets, you get volume. If the starch sets before the gas expands (e.g., if the crust hardens too fast), the loaf is constrained. Steam injection is used to keep the surface temperature low and the crust flexible (below its glass transition temperature) to allow this expansion to happen.

Part VI: The Glass Transition (The Crust)

Finally, we arrive at the true "Sourdough Glass": the crust.

As the surface of the dough exceeds $100^{\circ}\text{C}$, all water evaporates. The dehydration is extreme. The starch and protein on the surface undergo a phase change.

6.1 The Maillard Reaction

At $140^{\circ}\text{C}$, amino acids and reducing sugars react to form melanoidins—complex ring compounds that give the crust its brown color and roasted flavor. This is non-enzymatic browning.

6.2 Vitrification

As the crust cools, it enters a Glassy State.

In physics, a glass is an amorphous solid—a material that has the disordered molecular structure of a liquid but the mechanical rigidity of a solid. The sugars and gelatinized starches in the crust, now devoid of the plasticizing water, lock into place.

The "singing" of the bread—the crackling sound heard as a loaf cools—is the sound of physics. The crust is in a glassy state (brittle), while the crumb is in a rubbery state (soft). As the loaf cools, the crumb contracts slightly. The glassy crust cannot contract. Tension builds up until the glass fractures microscopically. Snap. Crackle. Pop.

Conclusion: The Lens of Science

The "Sourdough Glass" is not just a container; it is a lens. It reveals that the humble loaf is a triumph of soft matter physics. It is a foam generated by biological machines, stabilized by polymer networks, inflated by thermodynamic expansion, and frozen in time by a glass transition.

Understanding these forces does not diminish the romance of baking; it elevates it. When you hold a slice of sourdough up to the light and admire the open, glistening alveoli, you are not just looking at bread. You are looking at a record of nucleation, diffusion, strain hardening, and the delicate dance between the rubbery and the glassy states of matter. You are eating physics.

Reference:

- https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/pdf/2020/40/e3sconf_te-re-rd2020_03012.pdf

- https://bakerpedia.com/processes/gluten-hydration/

- https://thesourdoughbaker.com/gluten/

- https://www.pantrymama.com/developing-gluten-in-sourdough-bread/

- https://research.manchester.ac.uk/files/19835286/POST-PEER-REVIEW-PUBLISHERS.PDF

- https://boards.straightdope.com/t/bread-dough-co2-cannot-itself-form-bubbles-it-must-diffuse-into-existing-bubbles/441517

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248588089_Rheological_Properties_of_Dough_During_Mechanical_Dough_Development

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dtBqv-qIFLo

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222957076_Mechanism_of_gas_cell_stabilization_in_breadmaking_II_The_secondary_liquid_lamellae

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8588515/

- https://cooking.stackexchange.com/questions/128267/oven-springrelease-of-co2-in-to-the-surrounding-gas-cells

- https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/30200510/2009%20-%20mechanism%20of%20gas%20cell%20stabilization%20in%20bread%20making%20(i).pdf.pdf)

- https://krex.k-state.edu/items/38416dea-0c56-466d-a6eb-951ed6ba5bac