The wind-swept Loess Plateau of northern China, a landscape carved by the yellow earth and the passage of millennia, has long held secrets that defy the traditional narratives of history. For decades, local villagers in Shenmu, Shaanxi Province, would stumble upon jagged stones and fragments of jade while tilling their fields. They used the ancient bricks to build their pigsties, unaware that they were dismantling the remnants of a civilization that predated the accepted dawn of Chinese imperial power. They believed these stones were merely the debris of the Great Wall, a relic of a much later time.

They were wrong.

What lay beneath their feet was not a border wall of the Ming or Han dynasties, but a sprawling, fortified metropolis from the Neolithic era—a city of stone that flourished 4,500 years ago, challenging everything we thought we knew about the origins of Chinese civilization. This is Shimao, the "Stone City," a discovery so profound it has been hailed as one of the most significant archaeological finds of the 21st century.

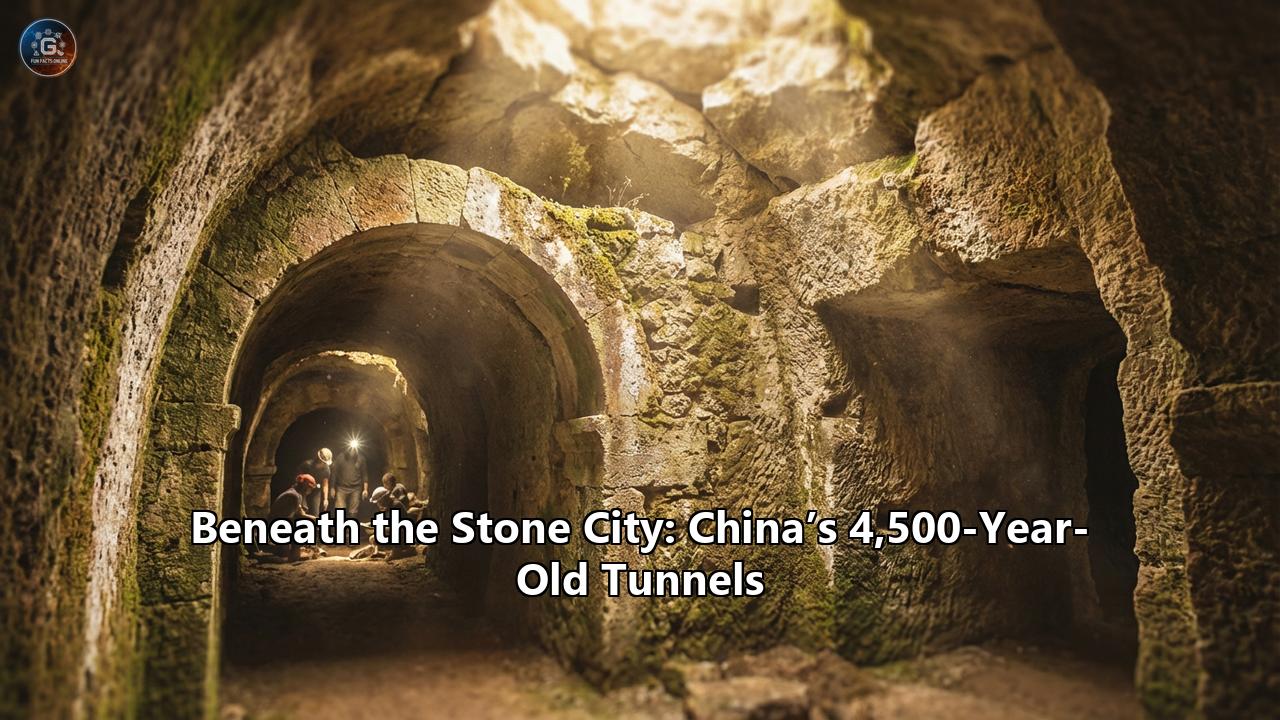

But the story of Shimao is not just about high walls and jade artifacts. Recent excavations in the broader Shimao cultural sphere—specifically at the neighboring site of Houchengzui—have revealed something even more chilling and sophisticated: a labyrinthine network of underground tunnels, designed for covert troop movements, surprise attacks, and desperate escapes. These tunnels, combined with the skull-filled pits of ritual sacrifice and the towering stepped pyramid of Shimao, paint a picture of a society that was powerful, paranoid, and perpetually prepared for war.

Part I: The Rediscovery of a Lost Empire

For much of the 20th century, the narrative of Chinese civilization was centered on the "Central Plains" (Zhongyuan) along the middle reaches of the Yellow River. The Erlitou culture (associated with the Xia Dynasty) and the later Shang Dynasty were seen as the singular cradle from which Chinese culture radiated. The northern steppes were viewed as a barbarian periphery, a cultural backwater inhabited by nomadic hunter-gatherers who contributed little to the refined civilization of the south.

Shimao shattered this Sinocentric model.

In 2011, when archaeologists from the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology began a systematic survey of the site, they were stunned by the sheer scale of what they found. Shimao was not a village; it was a fortress. Covering over 400 hectares (roughly 1,000 acres), it was the largest known city in China from the Longshan period (c. 2300 BC), dwarfing its contemporaries in the Central Plains.

The city was composed of three distinct layers: an Outer City, an Inner City, and a central "Imperial City" or Citadel, perched atop a natural loess hill. But unlike the rammed-earth walls of the Central Plains, Shimao’s defenses were built of stone—millions of cubic meters of rock, quarried, transported, and meticulously stacked to create walls that still stand several meters high today.

Part II: The Pyramid of the Loess Plateau

At the heart of Shimao stands its most imposing structure: the Huangchengtai, or "Imperial City Platform." For years, it was assumed to be a natural hill fortified with simple walls. However, excavations revealed that the entire hill had been terraced and encased in stone, transforming it into a massive, stepped pyramid.

Standing over 70 meters (230 feet) tall, the Huangchengtai is a monument to Neolithic engineering that rivals the pyramids of Egypt in its visual impact, if not its geometric precision. It consists of 11 stacked platforms, each reinforced with stone buttresses.

At the summit of this pyramid lay the palatial complex, the seat of power for the Shimao elites. Here, archaeologists found the remains of rammed-earth palaces with wooden pillars and tiled roofs, luxury that was unimaginable for the commoners living in the lower city. The pyramid was not just a residence; it was a fortress within a fortress, a "Forbidden City" four thousand years before the one in Beijing.

But the pyramid was also a spiritual center. Embedded within the stone walls of the Huangchengtai were curious artifacts that hinted at the city's spiritual life: pieces of jade.

The Jade in the WallsIn most Neolithic cultures, jade was buried with the dead as a sign of status. At Shimao, however, jade was used as construction material. Thousands of jade discs, blades, and scepters were inserted into the gaps between the stone blocks of the city walls. This was not accidental; it was a deliberate ritual act.

Archaeologists believe the jade served a spiritual defensive purpose—a magical barrier intended to repel malevolent spirits or curse enemy invaders. The sheer volume of jade found at Shimao suggests that this northern polity was incredibly wealthy, controlling trade networks that brought the precious stone from distances of over 1,000 miles.

Part III: The Tunnels of the North

While Shimao’s pyramid reaches for the sky, the true genius of this civilization’s defense lay underground. The "Shimao culture" was not limited to a single city; it was a network of fortified settlements stretching across the Ordos region and Inner Mongolia. It is here, at the sister site of Houchengzui, that the most startling discovery regarding the "tunnels" was made in late 2023.

For years, military historians assumed that complex underground warfare was a development of later eras. Yet, beneath the stone walls of Houchengzui, archaeologists unearthed a sophisticated triple-defense system that included a network of subterranean tunnels dating back 4,300 to 4,500 years.

The Anatomy of the TunnelsThese were not mere drainage ditches. The tunnels at Houchengzui were engineered for tactical warfare.

- Dimensions: The tunnels range from 1.5 to 6 meters deep (5 to 20 feet), with arched ceilings resembling the cave dwellings (yaodong) still used in the region today. They are roughly 1.5 meters wide and up to 2 meters high, allowing armed soldiers to move through them rapidly without crouching.

- The Radial Web: The tunnels radiate outward from the city center like the spokes of a wheel. They connect the inner barbican (a fortified gatehouse) to the outside of the city and to the defensive moats.

- Dual Purpose: The layout suggests a dual purpose: defense and offense. In a siege, the tunnels allowed the city's defenders to send messengers or supplies in and out without being seen. More aggressively, they served as sally ports—hidden exits that allowed shock troops to emerge behind the enemy lines, striking the besiegers from the rear before vanishing back into the earth.

This discovery rewrites the history of military engineering in East Asia. It proves that the "Northern Stone Cities" were locked in a state of endemic warfare, likely against rival factions or perhaps against the rising powers of the Central Plains. The people of the Shimao culture lived in a world of constant threat, and they responded by turning their cities into weaponized puzzles.

Part IV: The Gates of Death

Back at Shimao proper, the defensive architecture was equally paranoid and brilliant. The East Gate of the Outer City is one of the most complex prehistoric structures ever found.

To enter Shimao, a visitor (or invader) had to navigate a "baffled" entry. The gate was not a straight line. It involved a U-shaped enclosure known as a wengcheng or barbican. An enemy force breaching the first gate would find themselves trapped in a killing box, surrounded by high walls on three sides, with defenders raining down arrows and stones from above. This design, previously thought to have been invented during the chaotic Warring States period (c. 475–221 BC), was fully realized at Shimao nearly two millennia earlier.

The Skull PitsIt was under this East Gate that Shimao revealed its darkest secret. Archaeologists uncovered six pits containing 80 human skulls.

These were not respected ancestors. The skulls belonged almost exclusively to young women and girls. They showed signs of blunt force trauma and burning. Crucially, no other bones were found—the bodies were discarded elsewhere.

This was mass human sacrifice.

The placement of the pits directly beneath the city gate suggests a "foundation ritual." The blood and spirits of these victims were likely intended to consecrate the walls, buying protection from the gods through violence. The identity of the victims remains a subject of debate. Were they captives from a rival tribe? Slaves? Or selected members of Shimao’s own population? Genetic analysis suggests some victims may have come from the south, hinting at a violent conflict between the Shimao northerners and the ancestors of the Xia civilization.

Part V: The Face of the Gods

Amidst the stone and bone, Shimao has also yielded art of haunting power. The walls of the Huangchengtai are decorated with stone carvings that have no parallel in the Central Plains.

These carvings depict anthropomorphic figures—part human, part beast. They have large, staring eyes, fanged mouths, and are often flanked by serpents or raptors. Some scholars see a resemblance to the "taotie" motifs that would later dominate the bronzes of the Shang Dynasty, suggesting that the artistic DNA of Chinese civilization may have northern roots.

Others point to a more distant connection. The "god faces" of Shimao bear a striking stylistic similarity to the carvings of the Sanxingdui culture in Sichuan and even to iconography found in the Eurasian steppes. This hints that Shimao was a cosmopolitan hub, a "crossroads of civilization" that connected the agricultural heartland of China with the shamanistic cultures of Siberia and Central Asia.

The Sound of the Stone CityLife in Shimao was not just war and sacrifice. Archaeologists have found thousands of bone needles, indicating a thriving textile industry. They also discovered the earliest known "kouxian" or jaw harps—small musical instruments made of bone that are still used by ethnic groups across Asia today. One can imagine the sound of these harps twanging in the cold wind of the plateau, a moment of music in a city of stone.

Part VI: The Yellow Emperor and the rewriting of History

The discovery of Shimao has forced a re-evaluation of Chinese mythology. For millennia, Chinese texts have spoken of the "Yellow Emperor" (Huangdi), the legendary ancestor of the Han people who was said to have lived around 2700–2600 BC. He was a warrior-king who defeated rival chieftains and established the first state.

For a long time, the Yellow Emperor was considered pure myth. But Shimao’s location and dating overlap tantalizingly with the legends. Shimao is located in the region historically associated with the Yellow Emperor's tribe. The city’s militaristic nature, its advanced technology, and its rapid rise to power align with the stories of Huangdi’s wars.

While no inscription has been found to definitively link Shimao to the Yellow Emperor, the site proves that a powerful, state-level society existed in the north exactly when the legends say it did. Shimao may be the historical reality behind the myth—the physical shadow of the Yellow Emperor’s lost kingdom.

Part VII: The Collapse

After flourishing for three centuries, around 1800 BC, Shimao was abandoned. The end was likely not brought about by the war tunnels or the skull pits, but by the sky.

Paleoclimatic data indicates that around this time, the global climate shifted. The "4.2 kiloyear event" brought a sudden, sharp drop in temperature and a reduction in rainfall. The Loess Plateau, already a fragile ecosystem, dried up. The agriculture that supported Shimao’s massive population collapsed.

The city was not destroyed; it was deserted. Its people likely migrated south, blending into the populations of the Central Plains. They carried with them their technologies—the stamped-earth techniques, the jade rituals, the "taotie" motifs, and perhaps the memories of their great Stone City. These refugees may have become the artisans and warriors who helped build the Shang Dynasty, ensuring that the legacy of Shimao lived on, buried in the DNA of Chinese culture.

Conclusion: The Silent Sentinel

Today, Shimao stands silent. The wooden palaces have rotted away, leaving only the stone foundations of the pyramid. The tunnels of Houchengzui are dark and empty. But the message of the Stone City is clear.

Civilization did not rise from a single point. It was a tapestry woven from many threads—some from the fertile plains, others from the harsh northern steppes. Shimao was a pioneer, a city of stone in an age of earth, a fortress of tunnels in an age of open warfare. It reminds us that beneath the ground we walk on, history is waiting, ready to rewrite the story of who we are.

Reference:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shimao

- http://kaogu.cssn.cn/ywb/special_events/shanghai_archaeology_forum_2013/201308/t20130830_3927060.shtml

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339371503_Reconstruction_of_the_Shimao_citadel_gate_Planning_and_construction_of_Huangchengtai_gate_during_the_2nd_millennium_BCE_China

- https://archaeologymag.com/2023/12/underground-tunnels-in-ancient-stone-city-in-china/

- https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202209/19/WS6327acbaa310fd2b29e784e5_1.html

- https://www.chinadailyhk.com/hk/article/290885

- https://www.thearchaeologist.org/blog/houchengzui-stone-ruins-offer-glimpse-into-prehistoric-civilizations

- https://knewz.com/secret-tunnels-over-4000-years-old-unearthed-in-china-were-used-in-triple-defense-system-archaeologists-say/

- http://kaogu.cssn.cn/ywb/research_work/excavation_report/201706/W020180124632068199322.pdf

- https://www.archaeology.wiki/blog/2014/02/25/neolithic-evidence-of-organised-religion-found-in-shimao/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317141374_The_East_Gate_of_Shimao_An_architectural_interpretation