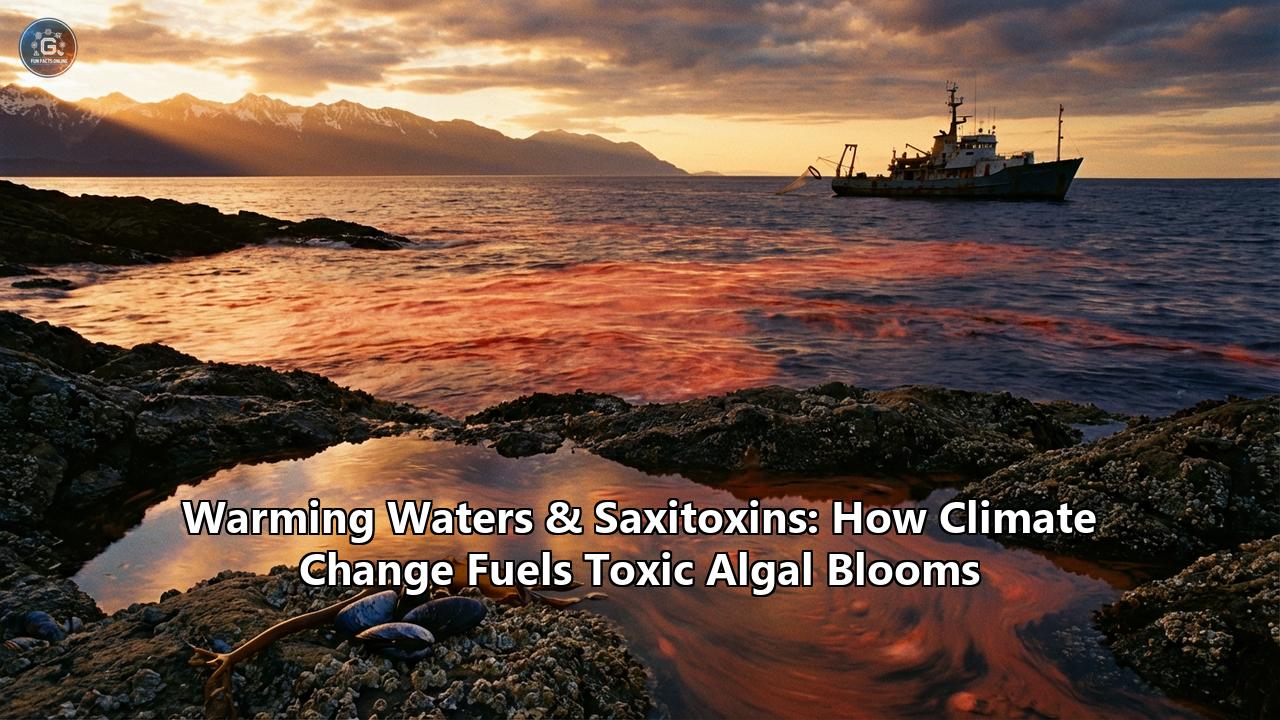

The summer of 2025 brought a chilling discovery to the windswept beaches of St. Paul Island in the Bering Sea. For generations, the Aleut community there has lived in rhythm with the ocean, harvesting fur seals and fish. But this year, the tide brought death. Dozens of Northern fur seals—majestic, intelligent marine mammals—washed ashore, their bodies convulsing in their final moments or already still.

For the first time in history, scientists conclusively linked these deaths not to starvation, entanglement, or viral disease, but to saxitoxin—a potent neurotoxin produced by microscopic algae. In the icy waters of the Arctic, where such toxic blooms were once a rarity, a new biological reality has taken hold.

This tragedy is not an isolated incident. It is a warning siren from our warming oceans. From the sun-baked coast of Southern California to the drinking water intakes of Lake Erie, a microscopic menace is rising. Climate change is not just making our waters hotter; it is fueling the proliferation of Paralytic Shellfish Toxins (PSTs), turning the base of the marine food web into a poisoned chalice.

This comprehensive guide explores the complex, often terrifying, and fascinating science behind how warming waters are supercharging toxic algal blooms, the mechanisms driving their expansion, and the cutting-edge technology humanity is deploying to fight back.

Part I: The Invisible Assassin

What are Saxitoxins?

To understand the threat, we must first understand the weapon. Saxitoxins (STXs) are among the most potent natural neurotoxins known to science. Produced by specific species of dinoflagellates (marine plankton) and cyanobacteria (freshwater blue-green algae), these toxins are chemically stable, heat-resistant, and tasteless. You cannot cook them out of a clam; you cannot freeze them out of a crab.

When ingested by humans—usually through contaminated shellfish—saxitoxins cause Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning (PSP). The mechanism is terrifyingly efficient: the toxin binds to voltage-gated sodium channels in nerve cells, effectively "plugging" them. This prevents nerves from firing instructions to muscles.

Symptoms can appear within minutes:- Phase 1: Tingling or burning (“pins and needles”) in the lips, tongue, and fingertips.

- Phase 2: Numbness spreads to the arms and legs; movement becomes uncoordinated (ataxia).

- Phase 3: Paralysis of the chest muscles. Without medical ventilation, the victim suffocates while remaining fully conscious.

For marine life, the consequences are equally devastating. But why is a warming planet making this ancient biological weapon more prevalent?

Part II: The Climate Connection

1. The "Atlantification" of the Arctic

Perhaps the most alarming shift is occurring in the Arctic. Historically, the waters of the Chukchi and Bering Seas were too cold to support massive blooms of Alexandrium catenella, the primary saxitoxin producer in North America. The cysts (dormant seeds) of these algae would lie on the seafloor, waiting for a warmth that rarely came.

But as sea ice retreats and water temperatures climb, the Arctic is undergoing "Atlantification." Warmer water from the Atlantic and Pacific is pushing north, carrying toxic algal cells with it.

- The Cyst Bed Giant: In recent years, scientists have mapped a massive "cyst bed" of Alexandrium stretching across the seafloor near Alaska—one of the largest ever documented globally.

- The Germination Trigger: As bottom waters warm, these cysts are now hatching in synchronized mass events. The open water, free of ice for longer periods, provides the sunlight needed for these hatched cells to photosynthesize and multiply exponentially.

2. The "Window of Opportunity"

In temperate regions like Puget Sound (Washington) and the Gulf of Maine, climate change is expanding the seasonal window for blooms.

- Past: Blooms were restricted to late spring/early summer.

- Present: Blooms are initiating earlier in the spring and persisting into late autumn.

- Mechanism: Warmer springs wake up the dormant cysts earlier. Warmer autumns prevent the water from cooling down enough to kill off the bloom, allowing the algae to produce toxins for months longer than usual.

3. The "Dual Bloom" Phenomenon

In 2024 and 2025, California witnessed a disturbing new trend: Dual Blooms. Historically, the region battled Pseudo-nitzschia (which produces domoic acid) or Alexandrium (saxitoxin) separately. Now, overlapping favorable conditions are allowing both to bloom simultaneously.

- The Impact: Marine wildlife rescue centers are overwhelmed. Sea lions are coming in with "cocktails" of toxins in their systems, complicating treatment and increasing mortality rates.

Part III: The Biological Paradox (The Science of Gene Expression)

Here is where the science gets incredibly nuanced. One might assume that "warmer water = more toxin." However, the biological reality is more complex.

The "Cold Stress" Trigger

Recent molecular studies on Alexandrium (specifically the sxt genes responsible for toxin production, like sxtA4 and sxtG) reveal a paradox.

- Optimal Growth vs. Optimal Toxicity: These algae often grow fastest in warmer water (around 16°C - 20°C). However, individual cells often produce more toxin per cell when they are under cold stress or sub-optimal temperatures (e.g., 12°C).

- Why? It is hypothesized that when growth slows down due to cold, the cell's internal machinery has excess energy (arginine) that gets shunted into toxin production rather than cell division.

So, why do blooms get more toxic with warming?

If cold makes individual cells more toxic, why is warming the problem?

- Biomass Over Quality: Even if individual cells are slightly less toxic in warm water, the sheer number of cells (biomass) explodes. A billion moderately toxic cells are far more dangerous than a million highly toxic ones.

- Range Expansion: Warming allows the algae to exist in places they never could before (like the Arctic).

- The Generalist: Other species, like Gymnodinium catenatum, are "warm-water lovers." Unlike Alexandrium, which prefers temperate waters, Gymnodinium thrives in the heat (22°C - 28°C). As oceans warm, Gymnodinium is expanding its range in Asia (China, Malaysia) and Europe, replacing cold-water species and bringing saxitoxins to new shores.

Part IV: The Freshwater Surprise – Lake Erie's Hidden Culprit

For decades, the narrative of saxitoxins was a saltwater story. But recently, the script flipped. In Lake Erie, notorious for its green, slime-like Microcystis blooms (which produce liver toxins), scientists detected saxitoxins.

The mystery was: Who is making it?

In December 2025, researchers from the University of Michigan finally cracked the case. The culprit is Dolichospermum , a type of cyanobacteria.

- The Driver: This organism thrives in a specific climate scenario: warming waters + low ammonium levels.

- The Implication: This discovery is a game-changer for freshwater management. Most monitoring focuses on microcystin. If saxitoxins are also present, water treatment plants need completely different protocols to ensure safe drinking water for millions of people.

Part V: The Human and Economic Toll

The "Alaskan Roulette"

For Indigenous communities in Alaska, the ocean is a grocery store. Clams, mussels, and crabs are staples of subsistence diets. But the unpredictability of modern blooms has turned harvest into a game of "Alaskan Roulette."

- The Butter Clam Issue: While mussels can flush toxins out of their system in weeks, Butter Clams (Saxidomus gigantea) are notorious for holding onto saxitoxins for up to two years. A bloom that happened in 2023 could still kill a harvester in 2025.

- Cultural Erasure: When elders cannot teach youth how to harvest safely because the "old signs" (like seasonality) no longer apply, cultural transmission is severed.

Economic Shockwaves

The fisheries industry faces losses in the millions annually due to closures.

- Dungeness Crab: In the Pacific Northwest, saxitoxins accumulate in the viscera (guts) of crabs. If levels are high, entire commercial seasons are delayed or cancelled, devastating coastal economies.

- Aquaculture: Shellfish farmers rely on clean water. Frequent closures force them to hold product for months, increasing costs and risk of mortality.

Part VI: Fighting Back – Technology & Innovation

Humanity is not standing still. We are deploying an arsenal of high-tech tools to detect these invisible assassins before they strike.

1. The "Lab in a Can" (ESP)

The Environmental Sample Processor (ESP) is an underwater robot that acts like a molecular biology lab.

- How it works: It sits on the seafloor, sucks in water, extracts DNA, and runs a generic test for algal species in situ.

- New for 2025: New sensors developed by NCCOS now allow these robots to detect the toxins themselves, not just the algae cells, transmitting real-time data to scientists on shore.

2. AI & Submersible Microscopes

In Norway and the US, researchers are using "submersible microscopes" coupled with Artificial Intelligence.

- The Innovation: The device takes holographic photos of every particle in the water. An AI algorithm, trained on thousands of images, identifies toxic species (like Alexandrium) in milliseconds and alerts authorities. This eliminates the days-long delay of sending water samples to a manual lab.

3. Nature-Based Solutions: Kelp Farming

A surprising ally has emerged: Sugar Kelp (Saccharina latissima).

- The Mechanism: Studies have shown that growing kelp alongside shellfish can mitigate blooms. The kelp competes for nutrients and may even produce allelopathic chemicals that inhibit the growth of toxic dinoflagellates. Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) is testing whether kelp "curtains" can shield oyster farms from toxic blooms.

Part VII: The Future – 2050 and Beyond

Climate models (using RCP 8.5 "business as usual" scenarios) paint a stark picture for the future of toxic blooms.

- Poleward Shift: The band of habitable water for temperate species like Alexandrium will continue to move north. By 2100, the Arctic Ocean could host annual, high-intensity blooms, fundamentally altering the Arctic food web.

- Tropical Contraction: Conversely, some tropical waters may become too hot for certain dinoflagellates, potentially reducing PSP risks in specific equatorial zones, though likely replacing them with other heat-tolerant toxin producers (like Ciguatera-causing algae).

- Synergy with Acidification: As oceans absorb CO2, they become more acidic. Early research suggests that lower pH may enhance the toxicity of some Alexandrium strains, meaning future blooms could be more potent even if they aren't larger.

Conclusion: Adapting to a Toxic Future

The rise of saxitoxins is a silent, invisible symptom of our changing planet. It challenges our ability to feed ourselves from the sea and threatens the biodiversity of our oceans.

However, the path forward is illuminated by science. Through the combination of Indigenous knowledge (monitoring changes in animal behavior), cutting-edge technology (AI and robotics), and global carbon reduction, we can adapt. The ocean is changing, and to survive, our relationship with it must evolve too. We can no longer take the safety of the harvest for granted; vigilance is the new price of seafood.

Reference:

- https://wildlife.org/toxic-tides-linked-to-northern-fur-seal-deaths/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11125744/

- https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/61439/noaa_61439_DS1.pdf

- https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/harmful-algal-blooms-linked-deaths-northern-fur-seals-southeast-bering-sea

- https://healthebay.org/domoic-acid-outbreak-2025/

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/11/251130205503.htm

- https://news.maryland.gov/dnr/2024/11/26/new-technology-helps-beat-back-harmful-algal-blooms/