Beneath the sun-drenched valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico, lies a world cloaked in eternal twilight, where the ancient dead still speak in vibrant shades of ochre, specular red, and Maya blue. For the Zapotec civilization, known in their own tongue as the Be'ena'a or the "Cloud People," death was never an abrupt termination of existence. Instead, it was a profound transition—an ascension to the heavens where deceased rulers and matriarchs transformed into powerful rain-bringing clouds, or binigulaza. To ensure these revered ancestors remained tethered to the earthly realm, the Zapotec developed one of the most sophisticated, spiritually charged funerary architectures in all of Mesoamerica. They constructed magnificent palatial estates, and directly beneath the patios of these elite residences, they carved elaborate, subterranean cruciform tombs. The living walked directly above the dead, sharing a domestic space where the veil between the mortal world and the sacred underworld was little more than a layer of cut stone and stucco.

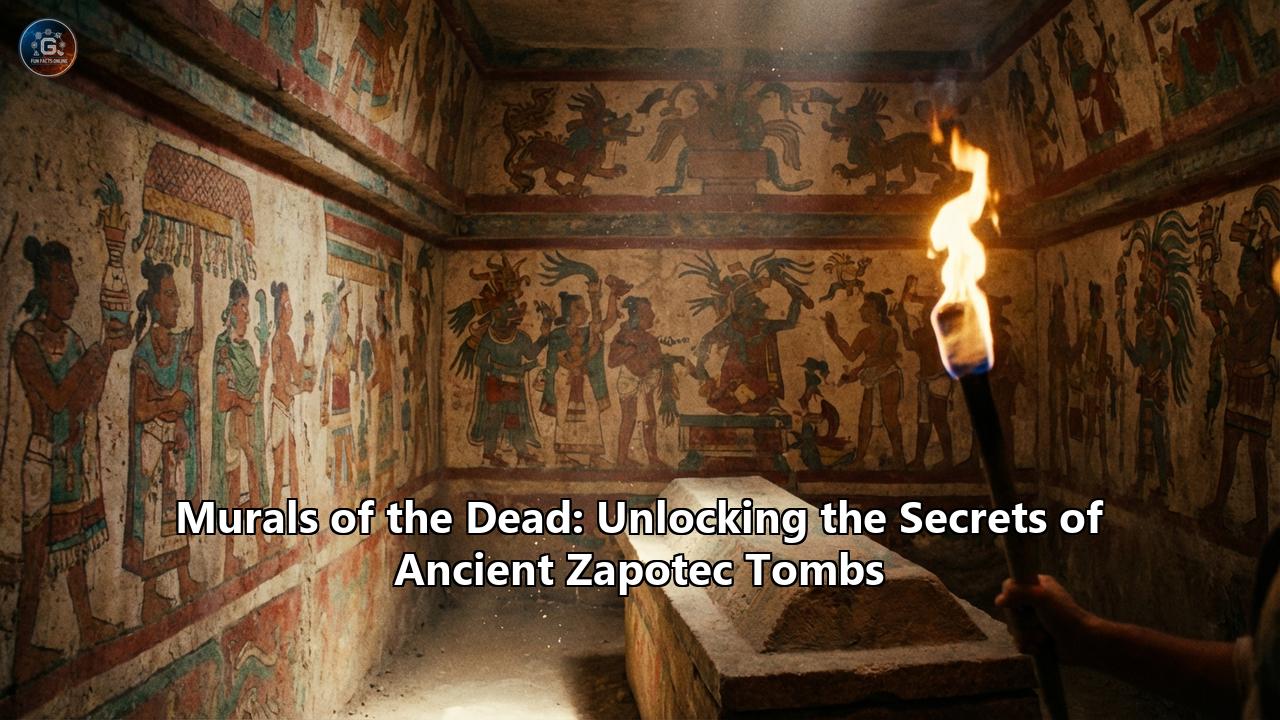

At the heart of this ancient cult of the ancestors are the extraordinary Zapotec tomb murals. Preserved in the cool, subterranean darkness for over a millennium, these polychrome masterpieces serve as windows into a complex cosmos. They are not merely decorations; they are intricate historical documents, dynastic records, and ritual roadmaps that guided the deceased through the perilous journey of the afterlife. Through a breathtaking combination of epigraphy, striking portraiture, and religious iconography, the murals of the dead unlock the secrets of Zapotec social hierarchy, their complex pantheon, and their deeply poetic understanding of mortality.

The Cosmology of the Cloud People

To understand the murals that adorn the walls of ancient Zapotec tombs, one must first understand the worldview that birthed them. Emerging around 700 BCE in the fertile, Y-shaped Oaxaca Valley, the Zapotec built a formidable empire that endured for over two millennia until the Spanish conquest. Their capital, the mountaintop metropolis of Monte Albán, was a marvel of urban planning, boasting monumental plazas, truncated pyramids, astronomical observatories, and a sprawling network of elite residential neighborhoods.

Yet, for all the grandeur of Monte Albán’s sunlit public spaces, its most sacred realms were intentionally hidden from view. The Zapotec practiced a "house-over-tomb" tradition, inextricably linking domestic life with ancestral veneration. When a patriarch or matriarch of a noble lineage died, their body was interred in a stone-lined chamber beneath the family courtyard. These spaces were not sealed away forever. Tombs were frequently reopened over generations to deposit new bodies, perform rituals, and update the genealogical murals painted on the walls.

The murals functioned as "epigraphic propaganda," establishing a direct lineage between the living descendants and the divine ancestors. By painting the founders of their noble houses alongside calendrical names and divine motifs, Zapotec elites validated their right to rule, control land, and exact tribute. The ancestors, wrapped in their finest textiles and surrounded by effigy urns filled with offerings of food and pulque, were believed to intercede with the great forces of nature—particularly Pitao Cocijo, the mighty god of rain and lightning, and Pitao Pezelao, the lord of the underworld.

The Masterpieces of Monte Albán: Tomb 104 and Tomb 105

Of the nearly 250 tombs excavated at Monte Albán, two stand out as the undisputed crown jewels of Mesoamerican funerary art: Tomb 104 and Tomb 105. Both constructed during the Late Classic period (circa 500–800 CE), they represent the zenith of Zapotec mural painting.

Tomb 104: The Untouched Guardian

Tomb 104 is an archaeological miracle. Discovered in 1937 by the legendary Mexican archaeologist Alfonso Caso, it is one of the rare Mesoamerican burials found entirely intact, having escaped the ravages of looters for over 1,500 years. Because the tomb was only used once and never reopened by the Zapotecs for subsequent burials, its contents and murals represent a perfectly preserved, single moment in ancient time.

The entrance to Tomb 104 immediately commands reverence. The façade features a classic Zapotec architectural motif known as the "double scapulary"—a geometric panel that mimics the stylized bodies of celestial serpents. Framed within a niche above the doorway sits a magnificent, 91-centimeter-tall ceramic effigy urn of Pitao Cocijo, the rain god. Originally covered in stucco and painted with touches of bright red, the deity wears an elaborate headdress and sits upon a jaguar-headed throne, serving as a fearsome, eternal sentinel guarding the threshold of the underworld.

Stepping past the heavy stone slab that once sealed the entrance, one enters a chamber vibrating with color. The walls were smoothed and coated with high-quality stucco, transforming the rough bedrock into a pristine canvas. The murals enveloping Tomb 104 are framed at the top by the "jaws of the sky"—a celestial motif that contextualizes the entire burial chamber as a sacred, cosmic space.

The murals themselves can be read as a linear narrative from front to back. On the southern wall stands an ancient male figure, his face rendered in profile while his torso faces forward. He is depicted holding a bag of copal—a highly prized, aromatic tree resin burned during pre-Hispanic rituals—or perhaps maize kernels, ready to be offered to the gods. Above him, a painted offering box features a bird grasping a grain of corn in its beak, surrounded by the calendrical glyphs "2 Serpent" and "5 Serpent".

On the northern wall, another male figure mirrors the first, holding his own bag of sacred offerings beneath a glyph representing a "sacrificial heart" and the calendrical name "1 Lightning". The focal point of the tomb, however, lies on the western back wall. Here, emerging directly from the stylized celestial jaws, is a disembodied human face accompanied by the glyph "5 Turquoise". Scholars believe this face represents the founding ancestor of the deceased’s lineage, waiting at the cosmic crossroads to welcome his descendant into the realm of the binigulaza.

Tomb 105: The Grand Procession of the Elders

If Tomb 104 is a pristine snapshot of a single burial, Tomb 105 is a sweeping, cinematic epic of dynastic power. Located in the northeastern sector of Monte Albán, beneath one of the city's largest and most luxurious palatial estates, Tomb 105 is a massive, cross-shaped subterranean structure consisting of a main antechamber and a deeply recessed burial chamber.

The murals of Tomb 105 demonstrate a mastery of line, proportion, and color palette, boasting a rich blend of deep reds, Maya blues, yellows, greens, pinks, and blacks. What makes Tomb 105 truly exceptional is its subject matter: an elaborate, wraparound procession of 18 richly attired men and women.

In a culture that deeply revered the wisdom of the aged, the figures in Tomb 105 are intentionally depicted as elderly. They possess heavily wrinkled faces, deeply developed beards, and toothless mouths—visual shorthand for ancestors who have long since passed into the realm of the divine. The men wear simple sandals and carry ritual sticks and bags of copal, which they are shown actively scattering upon the earth. The women stand barefoot, draped in elegantly woven skirts and quexquémetl (traditional Mesoamerican shawls).

Each figure in the procession is accompanied by a calendrical glyph that identifies them by name, revealing a highly organized genealogical record. Scholars analyzing these glyphs have identified specific historical individuals, such as Lady 12 Monkey Maize, Lord 4 Lightning Maize, and Lord 1 Iguana Slashed-Heart. The murals are meticulously arranged to show married couples, documenting both hypogamy and isogamy—marriages between individuals of lesser, equal, or greater noble status. This deliberate pairing of lords and ladies underscores that Zapotec political power was consolidated not just through male rulers, but through strategic marital alliances where women played equally pivotal roles in maintaining the spiritual and earthly authority of the lineage.

The Sensational 2026 Discovery: The Tomb of the Owl

While Monte Albán has long been recognized as the epicenter of Zapotec funerary art, the Oaxacan earth is still yielding staggering secrets. In early 2026, the global archaeological community was electrified by an announcement from the Mexican government and the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). Following an anonymous report of looting, archaeologists excavating in the municipality of San Pablo Huitzo, in the Etla Valley of Oaxaca, uncovered what Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum heralded as "the most important archaeological finding of the last decade in Mexico".

Dubbed "Tomb 10," this 1,400-year-old Zapotec burial complex dates to the Late Classic period (circa 600 CE). The tomb stands as a breathtaking testament to the enduring complexity of Zapotec cosmology, but it is its entrance that has captivated the world.

The Avian Guardian of the Threshold

As archaeologists cleared the dirt from the antechamber, they were confronted by a colossal, meticulously carved and stuccoed sculpture of a wide-eyed owl. In Zapotec mythology, the owl was a powerful, often feared omen. As a creature of the night, it was inextricably linked to the dark, subterranean domains of the underworld, serving as a psychopomp—a spiritual guide that escorted the souls of the dead across the perilous threshold between the world of the living and the realm of Pitao Pezelao.

Yet, this was no ordinary bird of prey. Nestled protectively within the beak of the giant owl is a beautifully sculpted human face. Experts believe this face is a portrait of the Zapotec lord interred within the tomb, or perhaps the revered ancestor to whom the funerary space was dedicated. By placing the human visage inside the beak of the death owl, the Zapotec visually communicated the soul's journey: the deceased had been consumed by death, only to be reborn and carried into the eternal night by the sacred avian messenger.

The Polychrome Procession of Huitzo

Passing beneath the gaze of the owl, the threshold into the main funerary chamber is framed by massive stone lintels bearing intricately carved friezes. These slabs act as a permanent, stone-carved registry of calendrical names, ensuring the identity of the lineage would outlast the fragile memories of the living. Flanking the doorway, carved deep into the stone jambs, are full-length portraits of a man and a woman. Adorned in elaborate headdresses and clutching ritual artifacts, these figures stand as eternal sentinels—ancestral guardians locked in stone, sworn to protect the sanctity of the burial space.

Inside the 5.5-meter-long chamber, archaeologists were stunned to find the walls completely covered in an expansive, immaculate polychrome mural. Despite being sealed in the humid earth for over fourteen centuries, the mineral-derived pigments—vibrant strokes of ochre, stark white, deep green, blood red, and celestial blue—retained an astonishing luminosity.

Much like the masterpieces of Monte Albán, the Huitzo mural depicts an elaborate funerary procession. A parade of elegantly rendered figures marches perpetually toward the tomb's entrance. In their hands, they carry heavy bags of copal resin. To gaze upon this mural is to witness a frozen moment of ancient grief and devotion. The painting does not just decorate the wall; it is a literal documentary of the very funerary rite that took place inside that chamber 1,400 years ago. The scent of burning copal, the rhythmic chanting of the priests, the brilliant colors of the feathered headdresses—all of it is captured and suspended in time through the masterful strokes of the ancient Zapotec artisan.

The Rituals of the Underworld: Blood, Smoke, and Stone

The recurring visual motifs across Tomb 104, Tomb 105, and the newly discovered Tomb 10 in Huitzo highlight the sensory and highly performative nature of Zapotec funerary rituals. Burying an elite family member was a monumental event that involved the entire community and required vast resources.

Central to these rituals was the burning of copal. Harvested from the sap of tropical trees, copal produces a thick, sweet, and intoxicating white smoke when dropped onto hot coals. For the Zapotecs, this smoke was not merely an olfactory pleasantry; it was the physical manifestation of prayer. As the smoke rose into the air, it formed a bridge between the dark, subterranean tomb and the sky above, carrying the pleas of the living directly to the cloud-dwelling ancestors. The prominence of copal bags in almost all Zapotec tomb murals underscores that maintaining a relationship with the dead required active, continuous feeding of the spirits through incense and offerings.

Alongside the smoke, the dead were equipped with literal sustenance. Tombs were packed with beautifully crafted ceramic vessels, many of which originally contained food, water, and intoxicating beverages like pulque, fermented from the sap of the agave plant. The journey to the afterlife was believed to be arduous, requiring energy and nourishment.

Furthermore, the architectural design of the tombs themselves reflected a deep understanding of sacred geography. Many of the most elite tombs were built in a cruciform (cross) shape. Long before the arrival of Christianity, the cross was a vital Mesoamerican symbol representing the axis mundi—the center of the universe where the four cardinal directions intersect. By laying the dead to rest at the center of a cruciform tomb, the Zapotec positioned their ancestors at the very navel of the cosmos, allowing their spiritual energy to radiate outward in all directions.

Mitla: The City of the Dead

While Monte Albán and Huitzo represent the height of Classic period Zapotec funerary art, the story of the Zapotec underworld does not end there. As the political power of Monte Albán waned around 850 CE for reasons still debated by archaeologists—ranging from prolonged drought to internal political fragmentation—the spiritual center of the Zapotec world shifted southeast to the city of Mitla.

The very name Mitla is a Hispanicized derivation of the Nahuatl word Mictlán, meaning "Place of the Dead." In the native Zapotec tongue, it was known as Lyobaa, the "Place of Rest". If Monte Albán was the political capital, Mitla was the Zapotec Vatican—a sacred city entirely devoted to the mechanics of death, ritual, and the afterlife.

Mitla's approach to funerary architecture was radically different from the painted murals of Monte Albán. Instead of wet stucco and mineral pigments, the walls of Mitla’s palaces and subterranean tombs are adorned with some of the most intricate stone mosaics in the ancient world. Known as grecas (stepped frets), these mosaics consist of tens of thousands of small, perfectly cut stones fitted together without mortar to form elaborate, repeating geometric patterns.

These patterns are not merely decorative. They represent the stylized scales of the feathered serpent, the jagged peaks of sacred mountains, and the infinite, interwoven fabric of lineage and blood. Beneath the stunning mosaic-covered palaces of Mitla lie massive cruciform tombs. According to 16th-century Spanish chroniclers, one of these subterranean chambers was believed to be the literal, physical entrance to the underworld—a cavernous abyss where the bodies of great kings and high priests were thrown into the darkness, sealing their covenant with the gods.

The Fragile Echoes of the Ancestors

The survival of these magnificent murals and sculptures into the modern era is nothing short of miraculous. The subterranean environment of Oaxaca—subject to shifting tectonic plates, encroaching tree roots, torrential seasonal rains, and the acidic decay of bat guano—is inherently hostile to the preservation of painted stucco.

Today, institutions like the INAH face a monumental challenge in conserving these delicate masterpieces. The vibrant reds and blues of Monte Albán and Huitzo are extraordinarily vulnerable to fluctuations in temperature and humidity. The simple act of human respiration—exhaling carbon dioxide and moisture into the enclosed space of a tomb—can cause ancient stucco to blister and flake away. It is for this reason that the breathtaking interiors of Tomb 104, Tomb 105, and the newly discovered Tomb 10 are strictly closed to the general public. Instead, scientists rely on high-resolution digital mapping, precise replicas, and meticulous climate control to study and share these wonders with the world without destroying them in the process.

The recent discovery of the Tomb of the Owl proves that the earth of Oaxaca has not yet given up all its secrets. With every new chamber unsealed and every new mural brought to light, archaeologists slowly decode the complex, poetic language of a civilization that refused to let death be the final word.

The Zapotec civilization did not vanish. Today, hundreds of thousands of Zapotec-speaking people continue to live in the mountains and valleys of Oaxaca. They still weave intricate textiles, cultivate maize, and in many communities, they still maintain deep, syncretic traditions of honoring their deceased during the Days of the Dead. The murals hidden beneath the ancient ruins are not relics of a dead and forgotten race; they are the vibrant, enduring legacy of the binigulaza—the old people of the clouds—who continue to watch over the valleys, eternally painted in the sacred colors of the earth and the sky.

Reference:

- https://english.elpais.com/culture/2026-02-09/the-underground-odyssey-that-led-archaeologists-to-a-zapotec-burial-site.html

- https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2026/02/11/zapotec-tomb-discovered-oaxaca-mexico

- https://out-of-eurasia.jp/en/publications/mexico/pdfs/19_ch17.pdf

- https://lugares.inah.gob.mx/en/node/5597

- https://wildfiregames.com/forum/applications/core/interface/file/attachment.php?id=73279&key=ec76b3dfd18e6277e5d4ff81094743f5

- https://www.gktoday.in/zapotec-owl-tomb-discovery-in-oaxaca/

- https://www.whatoaxaca.com/monte-alban-oaxaca.html

- https://www.mesoweb.com/mpa/montealban/montealban.html

- https://www.arthurbruso.com/post/domestic-abyss

- https://lugares.inah.gob.mx/en/pagina-de-elemento/1277

- https://www.livescience.com/archaeology/1-400-year-old-zapotec-tomb-discovered-in-mexico-features-enormous-owl-sculpture-symbolizing-death

- https://thedebrief.org/zapotec-death-owl-sculpture-reveals-ancient-mesoamerican-beliefs-in-immaculately-preserved-tomb/