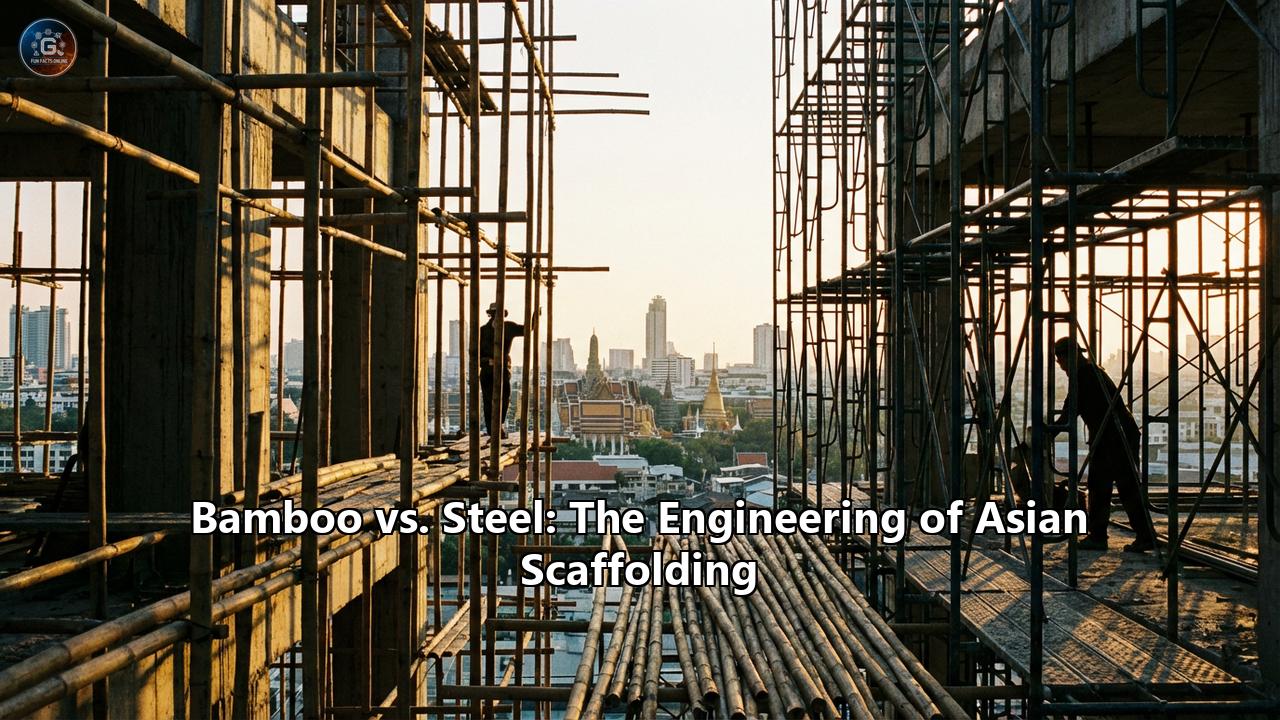

The skyline of Hong Kong is a testament to hyper-modernity. Glass and steel monoliths pierce the clouds, creating one of the densest and most futuristic urban jungles on Earth. Yet, look closer at the construction sites of these giants, and you will witness a scene that seems to defy the logic of modern engineering. Clinging to the sides of gleaming skyscrapers are not the rigid, prefabricated steel tubes common in London or New York, but an organic, chaotic-looking web of green bamboo poles.

This is the story of Bamboo vs. Steel, a battle of materials where ancient tradition doesn't just survive; it outcompetes modern technology. This article explores the engineering marvel of Asian bamboo scaffolding, delving deep into the physics, the culture, and the sheer audacity of building the future with grass.

Chapter 1: The Vegetable Steel – Material Science of Bamboo

To understand why a material as primitive-looking as bamboo is still used to wrap 80-story towers, one must look past the aesthetics and into the microscope. Bamboo is not wood; it is a grass. This biological distinction gives it structural properties that rival, and in some metrics exceed, industrial steel.

1.1 The Anatomy of Strength

Steel is isotropic—it has the same properties in all directions. Bamboo is anisotropic. It is designed by nature to do one thing perfectly: grow tall and resist the wind.

- The Culm: The hollow stem of the bamboo, known as the culm, is a masterclass in structural efficiency. Its cylindrical shape maximizes the moment of inertia, resisting bending forces while minimizing weight.

- The Vascular Bundles: The fibers of bamboo are most dense near the outer skin. This puts the strongest material exactly where the mechanical stress is highest during bending—at the perimeter. This is a natural optimization that engineers try to mimic with I-beams and hollow tubes.

- The Nodes: The horizontal rings (nodes) that punctuate the stalk act as natural stiffeners. They prevent the hollow tube from buckling (collapsing inward) when bent, a common failure mode in thin-walled steel pipes.

1.2 Bamboo vs. Steel: The Numbers

When we compare the two materials, the "primitive" grass holds its own:

- Tensile Strength: Bamboo has a tensile strength (resistance to being pulled apart) of roughly 28,000 per square inch. Mild steel is often rated around 23,000 psi. By weight, bamboo is stronger than steel in tension.

- Compressive Strength: While steel wins in pure compression, bamboo’s compressive strength is comparable to concrete.

- Weight: This is the killer app. Bamboo is incredibly light. A steel pole requires a crane or heavy lifting to move; a bamboo pole can be carried by a single worker, often with one hand. This changes the logistics of a construction site entirely.

1.3 The Species of Choice

Not just any bamboo will do. In the Hong Kong scaffolding trade, two specific species are the industry standard, sourced primarily from the Guangxi and Guangdong provinces of mainland China:

- Kao Jue (Bambusa Pervariabilis): These are the "workhorses." Thinner and more abundant, they are used for the horizontal and vertical grid of the scaffold.

- Mao Jue (Phyllostachys Pubescens): The "heavy lifters." These are thick, robust poles (at least 75mm in diameter) used for the critical load-bearing standards and diagonal bracing that keeps the structure rigid.

Chapter 2: The Engineering of the Grid

A bamboo scaffold is not a random collection of sticks; it is a highly sophisticated, three-dimensional truss system. It relies on flexibility rather than rigidity to survive the immense forces of wind and gravity.

2.1 The Double-Layer System

For modern high-rise construction, a Double-Layer Scaffold is the standard.

- The Outer Layer: This is the safety web. It holds the protective nylon mesh (to catch falling debris) and provides the primary structure.

- The Inner Layer: Located about 200-250mm from the building face, this layer is used by workers to access the wall for tiling, painting, or window installation.

- Working Platforms: Between these two layers, wooden planks are laid down to create walkways.

2.2 The Matrix: Zam, Hin, and Cheong

The structural integrity comes from a repetitive grid pattern, described by Cantonese terminology that every Sifu (master) knows:

- Zam (Needle): The vertical standards. These transfer the weight of the scaffold down to the ground or the transfer brackets.

- Hin (Thread): The horizontal ledgers. These tie the verticals together and provide the lateral support.

- Cheong (Spear): The diagonal braces. This is the most crucial element for stability. Without diagonals, a square grid would simply parallelogram and collapse. The Cheong triangulates the structure, locking it into a rigid form.

2.3 The Flexibility Factor

Steel scaffolding is rigid. If a typhoon hits a steel scaffold, the structure fights the wind. If the force exceeds the steel's yield point, it buckles and fails catastrophically.

Bamboo scaffolding is compliant. When a typhoon slams into Hong Kong, the bamboo scaffold dances. It bends, absorbs the energy, and flexes. This ductility allows it to survive wind loads that might shear a rigid metal bolt. It is the engineering principle of the willow tree versus the oak.

Chapter 3: The Art of the Knot

There are no bolts, screws, or clamps in a traditional bamboo scaffold. The entire structure, weighing tons and rising hundreds of feet, is held together by friction and plastic knots.

3.1 The Transition to Nylon

Historically, tough strips of bamboo skin were soaked in water and used as lashings. As they dried, they shrank, tightening the joint. Today, black nylon strips are the industry standard. They are rot-proof, UV resistant, and have a known tensile strength.

3.2 The "Man-Kuk" (Clove Hitch) and Beyond

The scaffolders, known locally as "Spiders," use a specific repertoire of knots that can be tied in seconds, often with one hand while hanging 50 stories in the air.

- The Clove Hitch: The foundational knot. It grips the pole tighter as the load increases.

- The Running Knot: Used for securing the ends of the nylon strips.

- The "Pig Cage" Knot: A complex lashing used to join multiple poles at a single intersection.

The genius of the nylon lashing is that it allows for slight movement. It doesn't crush the bamboo fiber like a metal clamp would. It distributes the stress around the circumference of the pole, preventing the hollow tube from splitting.

Chapter 4: The Economics and Logistics

Why does Hong Kong, one of the wealthiest cities in the world, use a "poor man's material"? The answer is ruthlessly capitalistic: speed and cost.

4.1 Speed of Erection

Bamboo is cut-to-fit on-site. If a steel scaffolder encounters a protruding balcony or an odd architectural angle, they need a specific prefabricated joint or must wait for a custom part. A bamboo scaffolder simply takes out a machete, cuts the pole to length, and ties it.

- Speed: A skilled team can erect roughly 20,000 square feet of bamboo scaffolding in a single day. Dismantling is even faster; the knots are cut, and the poles are slid down the center of the scaffold in a controlled freefall.

4.2 Cost Efficiency

- Material Cost: A bamboo pole costs a fraction of a steel pipe.

- Transport: You don't need a fleet of heavy trucks. A small lorry can carry enough bamboo to cover a house.

- Reusability: While steel lasts longer, bamboo is cheap enough to be semi-disposable. However, good poles are reused 3-5 times before being retired to easier jobs or discarded.

In the cutthroat world of Hong Kong real estate, where every day of delay costs millions, the agility of bamboo is unbeatable.

Chapter 5: The Human Element – The "Spiders"

The engineering is impressive, but the execution is superhuman. The bamboo scaffolders of Hong Kong are a legendary breed of worker.

5.1 Training and Hierarchy

It takes three years to become a licensed scaffolder. The training is an apprenticeship.

- The Apprentice: Spends the first year just passing poles and tying basic knots on the ground.

- The Junior: Allowed to work on the lower levels, learning the geometry of the grid.

- The Sifu (Master): The engineer-architect. They don't work from blueprints. They look at the building, visualize the load paths, and direct the structure from experience. They "feel" the structure.

5.2 Cultural Significance

The trade is steeped in tradition. Scaffolders worship Lu Ban, the patron saint of builders and carpenters. Before a major project begins, a roast pig is often offered to the spirits to ensure safety. It is a blend of pragmatic engineering and spiritual reverence.

5.3 The Danger

It is undeniably dangerous. "Spiders" work at extreme heights, often with minimal fall protection compared to Western standards (though regulations are tightening). They rely on their agility, balance, and the strength of their knots. The decline of the industry is partly due to the younger generation refusing to take on such a grueling and high-risk profession.

Chapter 6: The Future – Extinction or Evolution?

Is bamboo scaffolding doomed? The government of Hong Kong has begun incentivizing the use of metal scaffolding for safety reasons. The "Code of Practice for Bamboo Scaffolding Safety" becomes stricter every year.

However, bamboo has found a new argument for its survival: Sustainability.

- Carbon Footprint: Steel production is a massive carbon emitter. Bamboo is a carbon sink. It grows to maturity in 3-5 years, absorbing CO2 the entire time. A bamboo scaffold is, effectively, a carbon-negative structure.

- Waste: At the end of its life, bamboo is biodegradable. Steel scaffolding requires energy-intensive recycling.

As the world turns toward green architecture, the ancient methods of Asia are being re-evaluated not as relics of the past, but as blueprints for a sustainable future.

Conclusion

Bamboo scaffolding is more than just a construction technique; it is a symbol of Asian resilience and ingenuity. It represents a philosophy that values flexibility over rigidity, adaptation over domination, and harmony with nature over industrial brute force.

When you look at a Hong Kong skyscraper wrapped in its green cocoon, you are looking at a masterpiece of engineering where the organic and the synthetic meet. It is a reminder that sometimes, the best way to reach the sky is to grow there.

Reference:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QKk6c7pQ8fE

- https://interaksyon.philstar.com/trends-spotlights/2025/11/27/305594/why-is-bamboo-used-for-scaffolding-in-hong-kong-a-construction-expert-explains/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0udAHDJ4qhM

- https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e5cd082c50ea102c52e5bb0/t/5ed21155c189e7392e118f2d/1590825306312/bamboo_scaffolds.pdf

- https://scaffoldpole.com/bamboo-scaffolding/

- https://www.hkmemory.org/bamboo/?page_id=82&lang=en

- https://azscaffolding.com/how-to-build-with-scaffolding-bamboo/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/Construction/comments/qyqyei/bamboo_scaffolding_in_asia/

- https://multimedia.scmp.com/infographics/culture/article/3183200/bamboo-scaffolding/index.html

- https://www.thejakartapost.com/culture/2023/05/08/hong-kongs-bamboo-scaffolders-preserve-ancient-technique-.html

- https://altascaffolding.com.au/history-of-bamboo-scaffolding/

- https://www.timeout.com/hong-kong/news/hong-kong-will-start-to-phase-out-its-iconic-bamboo-scaffolding-032025