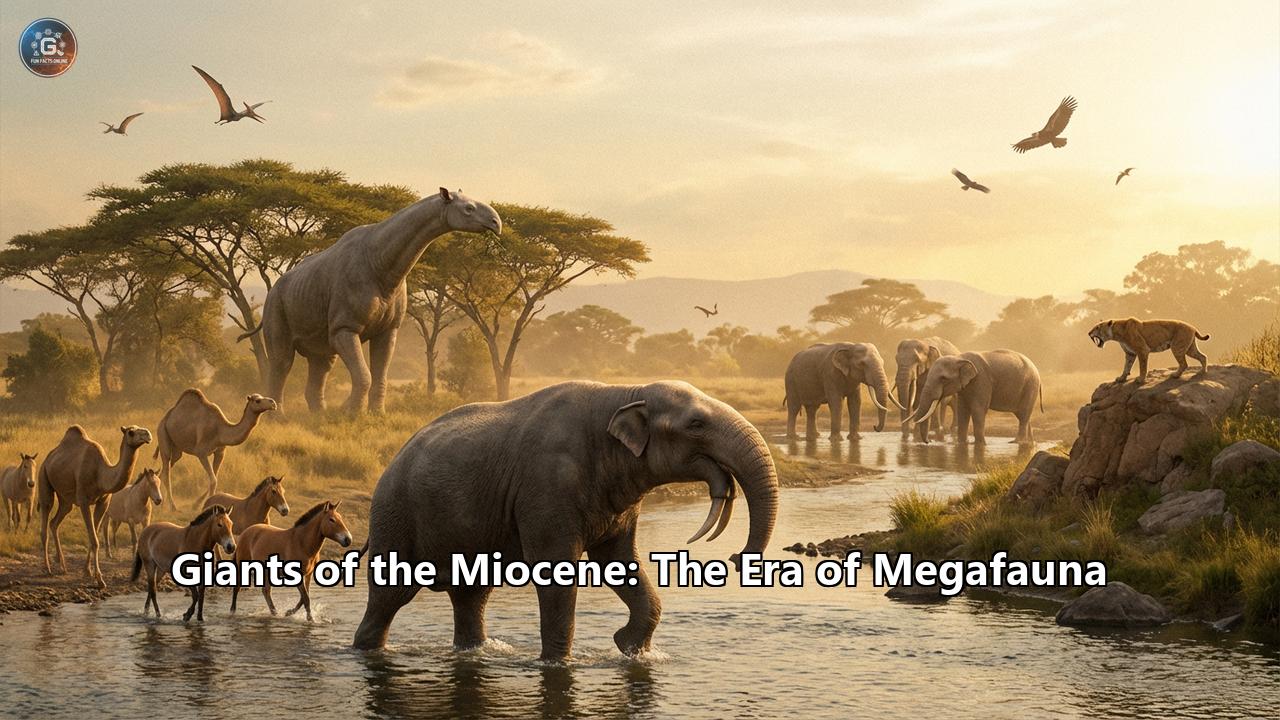

The Miocene Epoch, spanning from approximately 23 to 5.3 million years ago, is often called "The Golden Age of Mammals"—but to those who study its fossil record, it is better known as the Era of Giants. It was a time when the Earth was warmer, greener, and wilder than today, a planet where titanic beasts roamed vast savannas that stretched from Nebraska to Northern China, and where oceans teemed with predators large enough to swallow a great white shark whole.

This was not the alien world of the dinosaurs, nor the frozen wasteland of the Woolly Mammoth. The Miocene was a world tantalizingly similar to our own, yet populated by a cast of characters that seem like fantasy monsters: knuckle-walking horses, carnivorous sperm whales, crocodiles the size of buses, and birds with wingspans rivaling light aircraft.

Here is the comprehensive story of the Giants of the Miocene.

I. The World of the Miocene: A Planet in Transition

To understand the giants, we must first understand their stage. The Miocene was a pivotal chapter in Earth's history. The continents were drifting close to their modern positions, but key differences remained. North and South America were separated by a seaway, leaving the southern continent in "splendid isolation" for millions of years. India had just collided with Asia, thrusting the Himalayas into the sky and altering global weather patterns. The Mediterranean Sea would periodically dry up in a salt-encrusted catastrophe, only to refill in spectacular floods.

The Green RevolutionThe true engine of the Miocene’s megafauna was grass. During this epoch, distinct changes in atmospheric CO2 and drying climates caused forests to recede and grasslands to explode across the globe. This was the "Green Ocean"—vast seas of grass that offered an endless buffet for herbivores. But this new food source came with a price: grass is rich in silica, a microscopic abrasive that wears down teeth.

In response, herbivores evolved hypsodonty—high-crowned teeth that could withstand the grinding. As the grazers grew larger to process massive amounts of low-nutrient grass, the predators that hunted them had to scale up in an evolutionary arms race. The result was a global explosion of gigantism.

II. Lords of the Northern Continents: Eurasia and North America

In the Miocene, a land bridge connected Siberia and Alaska, turning the Northern Hemisphere into a superhighway for animals. The fauna here was a mix of the familiar and the bizarre.

1. The Bear-Dogs (Amphicyonids)

If you were to design the ultimate predator, you might combine the bone-crushing power of a bear with the speed and stamina of a wolf. Evolution did exactly this with the Amphicyonids, or "Bear-Dogs."

- The Alpha: Amphicyon ingens was the king of this group. Weighing up to 600 kg (1,300 lbs), it was heavier than a polar bear.

- Anatomy of a Killer: It possessed a massive skull with teeth capable of shearing flesh and crushing bone. Its legs were robust but long, suggesting it could sprint in bursts to ambush prey.

- The Extinction: For millions of years, they were the apex predators of North America and Europe. However, as the Miocene ended and prey became faster (like early horses), the Bear-Dogs couldn't keep up. They were slowly replaced by true bears and true canids, who split the niches of omnivore and pursuit predator between them.

2. The "Hell Pigs" (Entelodonts)

While technically peaking in the Oligocene, the Entelodonts made their final, terrifying stand in the early Miocene with the genus Daeodon (formerly Dinohyus, literally "Terrible Pig").

- Nightmare Fuel: Daeodon stood nearly 2 meters (6.5 ft) at the shoulder. It looked like a warthog injected with super-soldier serum. Its skull was 3 feet long, studded with bony flanges (bosses) likely used for display or absorbing blows during intraspecific combat.

- Diet: They were the ultimate opportunists. Their teeth show wear patterns indicating they crunched bones, roots, and likely scavenged or bullied other predators off kills. They were the "hyenas" of their day, but the size of a bison.

3. The Knuckle-Walking Horses (Chalicotheres)

Perhaps the strangest of all Miocene mammals were the Chalicotheres. Related to horses and rhinos (perissodactyls), they looked like a genetic mishap—a horse’s head on a gorilla’s body.

- The Giant: Moropus in North America and Chalicotherium in Eurasia.

- Evolutionary Quirk: Unlike their horse cousins who developed hooves for running, Chalicotheres developed massive claws.

- Behavior: They were browsers who sat on their haunches, using their long forelimbs and claws to hook tree branches and pull them down to their mouths—filling the niche that ground sloths would later occupy. Because their claws were so long, they walked on their knuckles to protect them, giving them a shambling, ape-like gait.

4. The Shovel-Tuskers (Gomphotheres)

The Miocene was the heyday of proboscideans (the elephant family). But these weren't your standard elephants.

- Platybelodon: Known as the "shovel-tusker," its lower jaw was elongated and flattened, terminating in two broad, flat tusks. For decades, paleontologists believed they used these jaws to dredge up swamp plants.

- Modern Theory: Micro-wear analysis suggests they actually used their lower jaws like a scythe to saw through tough vegetation and strip bark from trees. They were the landscapers of the Miocene, keeping the forests open.

- Deinotherium: The "Terrible Beast" was one of the largest land mammals ever, standing 4 meters (13 ft) tall. Unlike all other elephants, its tusks grew from its lower jaw and curved downward. They likely used these hooks to strip bark or anchor themselves against trees while sleeping.

III. The Island of Giants: South America

Isolated from the rest of the world, South America became an evolutionary laboratory where "Splendid Isolation" produced animals found nowhere else in the universe. Without placental carnivores (like cats or bears), other groups rose to take the throne.

1. The Terror Birds (Phorusrhacids)

In the absence of mammalian predators, dinosaurs reclaimed the top spot. The Phorusrhacids were flightless, carnivorous birds that terrified the continent.

- Kelenken guillermoi: The largest of them all, with a skull 28 inches long (the largest bird skull ever found). Standing over 3 meters (10 ft) tall, it could likely run as fast as a racehorse.

- The Hatchet Strategy: Unlike big cats that suffocate prey, Terror Birds used a "hit-and-run" tactic. Their beaks were shaped like pickaxes. They would sprint at prey, deliver a vertical, skull-crushing strike with the beak tip, and retreat before the prey could retaliate.

2. The Ruler of the Skies: Argentavis

While Terror Birds ruled the ground, the skies belonged to Argentavis magnificens.

- The Stats: With a wingspan estimated between 6 and 7 meters (20-23 ft), it was the size of a Cessna 152 airplane.

- Flight Mechanics: Argentavis was too heavy to take off by flapping alone. It relied on the strong thermal currents coming off the rising Andes Mountains and the grassy pampas. It was a master glider, soaring for miles without a single wingbeat.

- Diet: It was likely a scavenger, using its sheer size to intimidate Terror Birds and mammalian predators (like the pouched Thylacosmilus) away from their kills.

3. The King of the Swamp: Purussaurus

The Pebas System was a massive wetland covering much of the proto-Amazon. Here lived Purussaurus brasiliensis, a caiman of mythical proportions.

- Size: Estimates put it at 10–12.5 meters (33-41 ft) long and weighing 8.4 tons.

- Bite Force: Studies suggest a bite force of 69,000 Newtons (7 tons of pressure)—more than twice that of Tyrannosaurus rex.

- Prey: It hunted anything it wanted, including 3-meter turtles (Stupendemys) and 700kg rodents. The bite marks on fossilized turtle shells match Purussaurus teeth perfectly, showing it could crush a car-sized shell like a walnut.

IV. The Dreamtime Giants: Australia

Australia’s Miocene forests were home to the ancestors of the "Megafauna" that early humans would later encounter.

- The Demon Duck of Doom: Dromornis stirtoni, or "Stirton’s Thunder Bird," stood 3 meters tall and weighed 500 kg. Related to ducks and geese, it had a beak powerful enough to shear tough stems—or crush skulls, though it was likely a herbivore.

- The Marsupial Lion: Wakaleo was a precursor to the famous Pleistocene Thylacoleo. About the size of a leopard, it had bolt-cutter teeth and a thumb claw that acted like a switchblade, used to disembowel prey.

- The Giant Platypus: Obdurodon tharalkooschild was a carnivorous platypus nearly a meter long. Unlike the modern toothless version, Obdurodon retained functional teeth to crunch through turtles and crustaceans.

V. Monsters of the Deep: The Miocene Ocean

The Miocene oceans were warmer and supported vast forests of kelp, creating a nursery for marine mammals. This abundance of food allowed for the evolution of the most terrifying marine predators in history.

1. Megalodon (Otodus megalodon)

No article on the Miocene is complete without the Megalodon.

- The Scale: Reaching lengths of 15–18 meters (50-60 ft), it was three times the size of a Great White. Its teeth were the size of a human hand.

- Hunting Strategy: Fossil evidence shows they targeted small to medium-sized baleen whales (which were abundant). They attacked the chest cavity to crush the heart and lungs, a brute-force strategy distinct from modern Great Whites.

2. The Leviathan (Livyatan melvillei)

For a long time, we thought Megalodon had no peers. Then, in 2008, paleontologists in Peru’s Pisco Formation found a rival: Livyatan.

- The Anti-Sperm Whale: Unlike modern sperm whales that suck up squid, Livyatan had functional teeth in both jaws—teeth that were 36 cm (14 inches) long, the largest biting teeth of any animal, ever.

- Clash of Titans: Livyatan occupied the same waters as Megalodon and hunted the same prey. It is one of the few times in Earth's history where a massive apex reptile (shark) and a massive apex mammal (whale) competed directly for dominance.

VI. The Primate Prelude

While the giants stomped and swam, a quieter revolution was happening in the trees. The Miocene was the epoch of the Apes.

- Pierolapithecus: Found in Spain, this 13-million-year-old ape had a flat ribcage and stiff lower spine—key adaptations for upright climbing that we (humans) inherited.

- Sivapithecus: Found in the Siwalik Hills of Pakistan, this ape is practically indistinguishable from the modern Orangutan in facial structure, proving that the lineage of the "red ape" stretches back deep into the Miocene.

- Gigantopithecus: While famous in the Pleistocene, the lineage of "Giganto" began in the Miocene with Indopithecus. These massive apes eventually grew to 3 meters tall, likely living on a diet of bamboo in the shrinking forests.

VII. The End of the Giants: The Middle Miocene Disruption

All empires fall. Around 14 million years ago, the Middle Miocene Disruption occurred.

A sharp drop in atmospheric CO2 (likely sequestered by the weathering of the rising Himalayas) caused global temperatures to plummet. The Antarctic ice sheet expanded, locking up water and lowering sea levels.

- The Impact: The lush subtropical forests that covered much of Eurasia and North America withered, replaced by arid steppes and deserts.

- The Extinction: The browsers—like the Chalicotheres and many Gomphotheres—starved as their leafy food vanished. The "Crocodile Empire" of South America collapsed as the massive wetlands of the Pebas System dried up. The oceans cooled, killing off the tropical whales that Megalodon fed upon, setting the stage for the giant shark's eventual demise in the Pliocene.

Conclusion

The Miocene was a time of experimentation, a biological "sandbox" mode where evolution tested the limits of size and form. It shows us that the Earth is capable of supporting ecosystems far more grandiose than what we see today. The bones of Argentavis, Megalodon, and Deinotherium stand as silent monuments to an era when the Earth truly belonged to the giants.

Reference:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyaenodonta

- https://www.mindat.org/taxon-4851598.html

- https://australian.museum/learn/australia-over-time/extinct-animals/dromornis-stirtoni/

- https://www.unsw.edu.au/newsroom/news/2017/12/a-new-species-of-marsupial-lion-tells-us-about-australias-past-

- https://australian.museum/learn/australia-over-time/extinct-animals/wakaleo-vanderleuri/

- https://www.sci.news/paleontology/science-obdurodon-tharalkooschild-fossil-platypus-01518.html

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sivapithecus

- https://grokipedia.com/page/Sivapithecus

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyaenodon

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Miocene_disruption