The Invisible Nervous System of the Modern World

In the quiet hum of a server room in Northern Virginia, a single anomaly in a data stream triggers an automated rerouting of internet traffic, saving millions of dollars in potential downtime. Simultaneously, on a wind-swept plain in Patagonia, a wind turbine feathers its blades by two degrees in response to a gust that hasn't even hit it yet, but was detected by a LIDAR sensor 300 meters upwind. High above the Earth, a satellite adjusts its solar panels to catch the optimal photon flux, while deep in the Atlantic, a fiber-optic cable repeater boosts a signal carrying the financial transactions of a hemisphere. And in a hospital room in Tokyo, a silent alarm notifies a nurse that a patient’s heart rhythm has shifted subtly, minutes before a cardiac arrest would have occurred.

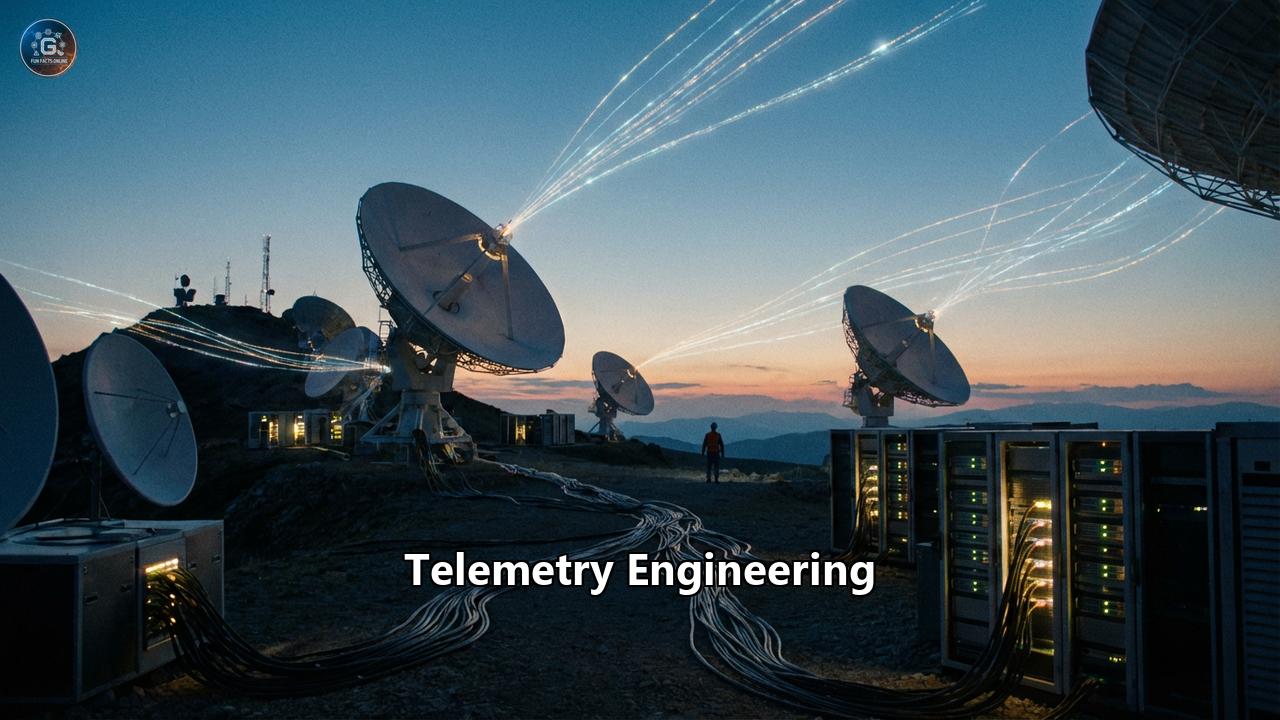

These disparate events, separated by thousands of miles and vastly different industries, share a common, invisible backbone: Telemetry Engineering. It is the discipline of measuring from a distance, the art of translating the physical world into digital signals, transmitting them across the void, and reconstructing them into knowledge that drives action. It is the nervous system of our technological civilization, sensing, transmitting, and processing the vital signs of the machines, environments, and systems upon which our lives depend.

The Anatomy of Telemetry: From Sensor to Screen

To understand telemetry engineering is to understand the journey of a datum. It is a journey that transcends the traditional boundaries of electrical, mechanical, and software engineering, requiring a synthesis of disciplines that is rare in the technical world. The telemetry engineer must be part physicist, understanding the phenomenon being measured; part electrical engineer, designing the circuits to capture it; part communications expert, ensuring the signal survives the noise of transmission; and part data scientist, making sense of the flood of information that arrives at the other end.

1. The Genesis of Data: Sensors and Transducers

Every telemetry system begins at the edge, at the interface between the physical and the digital. The sensor is the sensory organ of the machine. In the early days of telemetry, these were crude mechanical linkages—mercury manometers or bimetallic strips. Today, they are marvels of micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) and quantum physics.

Consider the inertial measurement unit (IMU) found in everything from your smartphone to a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. These chips, smaller than a fingernail, contain microscopic vibrating structures that detect the Coriolis effect to measure rotation and capacitance changes to measure acceleration. A telemetry engineer doesn't just "buy" a sensor; they must understand its drift, its bias, its temperature dependence, and its noise floor. In a Formula 1 car, a suspension potentiometer must survive 5g vibrations and 100°C temperatures while delivering sub-millimeter precision. If the sensor lies, the entire telemetry chain propagates a fiction.

Transducers convert these physical phenomena—pressure, light, temperature, strain—into electrical signals (voltage, current, or frequency). The conditioning of this signal is the first critical engineering challenge. Amplifiers must boost weak signals without amplifying noise. Filters must strip away the electromagnetic interference (EMI) generated by nearby motors or power lines. This "signal conditioning" phase determines the fidelity of the entire system.2. The Translation: Analog-to-Digital Conversion (ADC)

The physical world is continuous; the digital world is discrete. The Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) is the bridge between them. Telemetry engineering demands a rigorous trade-off analysis here. A 24-bit ADC offers incredible precision but generates a massive data volume that might clog the bandwidth of the transmission link. A 12-bit ADC is faster and lighter but might miss subtle trends.

Sampling theory—specifically the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem—is the law of the land here. To perfectly reconstruct a signal, one must sample at least twice as fast as the highest frequency component of that signal. But in the real world of telemetry, "oversampling" is often used to reduce noise and improve resolution, a technique that trades bandwidth for clarity.

3. The Courier: Data Transmission and Modulation

Once digitized, the data must move. This is where telemetry engineering intersects heavily with telecommunications. The choice of medium dictates the architecture of the system.

- Wired Telemetry: In industrial plants (SCADA systems), 4-20mA current loops have been the standard for decades. They are robust, immune to voltage drops over long cables, and simple to debug. However, they are being replaced by digital fieldbuses (Modbus, Profibus, EtherCAT) that allow bidirectional communication—not just reading the sensor, but configuring it remotely.

- Wireless RF Telemetry: This is the realm of the "link budget." An aerospace telemetry engineer must calculate whether a 5-watt transmitter on a rocket can be heard by a ground station 500 kilometers away, accounting for atmospheric attenuation, antenna gain, and the Doppler shift caused by the rocket's hypersonic speed. Modulation techniques like PCM/FM (Pulse Code Modulation / Frequency Modulation) or the more modern SOQPSK (Shaped Offset Quadrature Phase Shift Keying) are chosen to pack as many bits as possible into a limited slice of the radio spectrum.

- The IoT Revolution (LPWAN): For widespread, low-power telemetry (like smart water meters or agricultural sensors), engineers use Low Power Wide Area Networks (LPWAN) like LoRaWAN or NB-IoT. These protocols enable a sensor to run on a single AA battery for ten years, transmitting small packets of data over kilometers, by trading off data rate for range and power efficiency.

4. The Brain: Data Processing and Observability

The "receiver" is no longer just an antenna; it is a cloud. The modern telemetry stack feeds into massive data lakes and real-time stream processing engines like Apache Kafka. Here, the discipline shifts from hardware to software.

The concept of Observability has emerged as the software-native evolution of telemetry. In complex microservices architectures, it is not enough to know if a server is up (monitoring); we need to know why a specific request failed. Observability relies on three pillars of software telemetry:

- Metrics: Aggregatable numbers (e.g., "CPU load is 80%").

- Logs: Discrete events (e.g., "Database connection failed at 10:00:01").

- Traces: The journey of a single request as it hops between dozens of microservices.

A telemetry engineer in the software domain designs "pipelines" to collect these signals without slowing down the application itself, a technique known as low-overhead instrumentation.

The Sectors: Telemetry in Action

The principles of telemetry are universal, but their application is highly specialized. The constraints of a pacemaker are vastly different from those of a Mars rover.

Aerospace and Defense: The High Stakes Game

In aerospace, telemetry is often the only product of a test flight. If a prototype aircraft crashes, the physical evidence may be destroyed, but the telemetry data streamed in the final milliseconds tells the story.

- The "Blackout" Problem: When a spacecraft re-enters the atmosphere, the plasma sheath generated by extreme heat blocks radio waves. Engineers have had to develop creative solutions, such as the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System (TDRSS) to look "down" through the hole in the plasma wake, or storing data on board to transmit after the plasma subsides.

- Deep Space Network: Communicating with Voyager 1, now billions of miles away, requires telemetry engineering at the limits of physics. The signal received on Earth is a billionth of a billionth of a watt. Massive antennas and cryogenically cooled amplifiers are used to extract this whisper of data from the cosmic background noise.

Motorsport: Formula 1 as a Data Lab

A modern Formula 1 car is a telemetry device with an engine attached. Over 300 sensors generate gigabytes of data during a race.

- Real-Time Strategy: Teams run "Monte Carlo simulations" during the race, feeding live telemetry (tire degradation rates, fuel burn, driver inputs) into models that predict thousands of possible race outcomes to decide the exact lap to pit.

- The "Digital Twin": Telemetry allows engineers to compare the real car’s performance against the virtual car in the simulator. If the real car is understeering more than the model predicts, they know either the setup is wrong, or the wind tunnel model itself has a flaw.

Healthcare: The Internet of Medical Things (IoMT)

Cardiac telemetry units in hospitals were the pioneers, but "Remote Patient Monitoring" (RPM) is the future.

- Wearable Telemetry: Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs) for diabetics transmit blood sugar levels to a smartphone every 5 minutes via Bluetooth. The engineering challenge here is bio-compatibility and miniaturization. The sensor must pierce the skin without causing immune rejection and run on a tiny battery for weeks.

- Alert Fatigue: A major human-factors challenge in medical telemetry is handling the volume of alarms. Engineers are now using AI to filter out "artifact" noise (like a patient brushing their teeth looking like a lethal arrhythmia) so that nurses only see clinically significant alerts.

Industrial IoT (IIoT) and SCADA

In the utility sector, telemetry keeps the lights on.

- Phasor Measurement Units (PMUs): These devices measure the voltage and phase angle of the electrical grid 60 times per second, synchronized via GPS atomic clocks. This "synchrophasor" data allows operators to see the "heartbeat" of the grid in real-time, detecting oscillations that could lead to a massive blackout like the 2003 Northeast outage.

- Predictive Maintenance: Instead of changing oil in a compressor every 6 months, telemetry sensors listen to the acoustic signature of the bearings. When the vibration frequency shifts, indicating microscopic pitting, the system orders its own maintenance.

The Protocols: The Language of Machines

Telemetry data needs a standard language to travel from the edge to the cloud. The "Protocol Wars" have given us several dominant standards, each optimized for different constraints.

- MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport):

The lightweight champion. Originally developed by IBM to monitor oil pipelines over unreliable satellite links, MQTT is now the de facto standard for IoT.

It uses a Publish/Subscribe model. A sensor (Publisher) sends data to a central Broker. The Broker then sends that data to anyone who has "Subscribed" to it (e.g., a database, a mobile app, an alert system).

Why it wins: It is incredibly bandwidth-efficient and handles unstable connections gracefully. If the connection drops, the broker can hold the "last known good" value.

- CoAP (Constrained Application Protocol):

The web for tiny things. While MQTT runs over TCP (which requires a stable "handshake"), CoAP runs over UDP (fire-and-forget). It is designed to look like HTTP (the web), using GET and POST commands, but for devices with mere kilobytes of RAM.

Use case: Smart light bulbs or simple environmental sensors where overhead must be absolutely minimal.

- OPC UA (Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture):

The industrial diplomat. In a factory, you might have a Siemens PLC, a Rockwell automation arm, and a Mitsubishi conveyor belt. They don't speak the same language. OPC UA is the universal translator, a robust, secure, platform-independent standard that allows these disparate industrial systems to share telemetry data with the IT world.

- OpenTelemetry (OTel):

The software unifier. In the cloud world, we used to have fragmented tools—one for logs, one for metrics, one for traces. OpenTelemetry is a massive open-source project (second only to Kubernetes in activity) that provides a single standard for generating and collecting cloud telemetry. It prevents "vendor lock-in," allowing engineers to switch backend analysis tools without rewriting their code.

The Challenges: The "Last Mile" of Engineering

Telemetry is not "plug and play." It is fraught with difficulties that keep engineers awake at night.

1. The Data Deluge and "Data Gravity"We are generating more telemetry than we can store. A jet engine can generate terabytes of data in a single flight. Transmitting all of this to the cloud is cost-prohibitive and slow.

- Solution: Edge Computing. We are moving the "brain" to the sensor. Instead of sending 10,000 vibration readings per second to the cloud, the sensor itself runs a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithm and only transmits the summary: "Bearing health is 98%." This reduces bandwidth usage by 99.9% while keeping the insight.

If a sensor in New York says an event happened at 12:00:00.001 and a sensor in London says 12:00:00.002, did they happen at the same time? In high-frequency trading or power grid stabilization, a millisecond is an eternity.

- Solution: PTP (Precision Time Protocol). Unlike the standard NTP (Network Time Protocol) which is accurate to milliseconds, PTP uses hardware timestamps on the Ethernet packets themselves to achieve microsecond or even nanosecond accuracy across a local network.

Many telemetry sensors must be placed where battery replacement is impossible—embedded in concrete bridges, buried under city streets, or tracking wildlife.

- Solution: Engineers are developing sensors that power themselves. They harvest energy from the vibration of the bridge, the temperature differential (thermoelectric) of a pipe, or even the ambient radio waves (RF harvesting) in the air.

For years, telemetry was an afterthought in security. "Who would want to hack a thermostat?" The answer: everyone. Mirai, a botnet composed of hacked IoT cameras, took down major chunks of the internet in 2016.

- The Engineering Response: We are moving toward "Zero Trust" architecture in telemetry. Every sensor must have a cryptographic identity (like an X.509 certificate). Every data packet must be encrypted (TLS 1.3). And we are seeing the rise of Data Diodes—hardware devices that allow data to physically flow only in one direction (out of the nuclear plant), ensuring that no hacker can ever send a command in*.

The Future: Telemetry 2.0

As we look toward the horizon, telemetry is evolving from "Remote Measurement" to "Remote Intelligence."

AI at the Edge (TinyML): We are shrinking machine learning models to run on microcontrollers. A telemetry camera in a national park won't just stream video; it will run an onboard AI model to identify "Poacher" vs. "Hiker" and only transmit the alert. New Space and Satellite IoT: Companies like Swarm (acquired by SpaceX) are launching shoebox-sized satellites to provide global telemetry coverage. Soon, there will be no "dead zones" left on Earth. A shipping container in the middle of the Pacific will be as connected as a server in Silicon Valley. The feedback loop: The ultimate goal of telemetry is not just to watch, but to act. We are closing the loop, moving from "Telemetry" (measurement) to "Telecommand" (control) to "Autonomy." The telemetry system of the future will not need a human operator. The grid will heal itself. The car will dodge the accident. The server will patch its own code.In this automated future, the telemetry engineer is the architect of the senses, the builder of the nerves that allow our digital creations to feel the world around them. It is a field that remains largely invisible, buried in protocols and packets, but it is the silent pulse of the machine age.

Reference:

- https://automationcommunity.com/what-is-telemetry/

- https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/definition/telemetry

- https://smartdev.com/the-convergence-of-ai-and-iot-in-2025/

- https://dewesoft.com/blog/how-aerospace-telemetry-works

- https://fourdata.io/telemetry-performance-5-common-mistakes-to-avoid/

- https://wraycastle.com/blogs/knowledge-base/understanding-telemetry-in-telecommunications-a-simple-guide-for-everyone

- https://fordewind.io/choosing-the-right-iot-protocol-mqtt-coap-or-http/

- https://www.graphapp.ai/engineering-glossary/cloud-computing/iot-protocols-mqtt-coap

- https://www.emqx.com/en/blog/mqtt-vs-coap

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/computer-networks/difference-between-coap-and-mqtt-protocols/

- https://www.ien.com/operations/blog/22958012/how-5gs-speed-advantage-can-backfire-on-security-teams

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zH19CUbFcm4

- https://community.cadence.com/cadence_blogs_8/b/life-at-cadence/posts/formula-1-how-f1-teams-use-telemetry-control-analytics-to-go-faster

- https://nationaltelemetryassociation.org/is-remote-virtual-telemetry-the-future-of-healthcare/