The wind does not always blow, and the sun does not always shine. This simple, immutable fact remains the single greatest hurdle in humanity’s race toward a net-zero future. As we aggressively dismantle the fossil fuel infrastructure that has powered civilization for two centuries, we are replacing predictable, dispatchable power with weather-dependent variables.

We have mastered the art of generating green energy; solar panels are now the cheapest source of electricity in history, and wind turbines are engineering marvels. But we have not yet mastered the art of keeping it. The grid needs a buffer—a massive, responsive, and bottomless reservoir to store the noon sun for the evening peak and the midnight gale for the morning calm.

For the last decade, the answer has been lithium-ion batteries. They are brilliant, dense, and fast. But they are also expensive, rely on strained supply chains of rare earth minerals, degrade over time, and carry a significant fire risk. They are the sprinters of the energy world, perfect for short bursts. But the grid needs marathon runners.

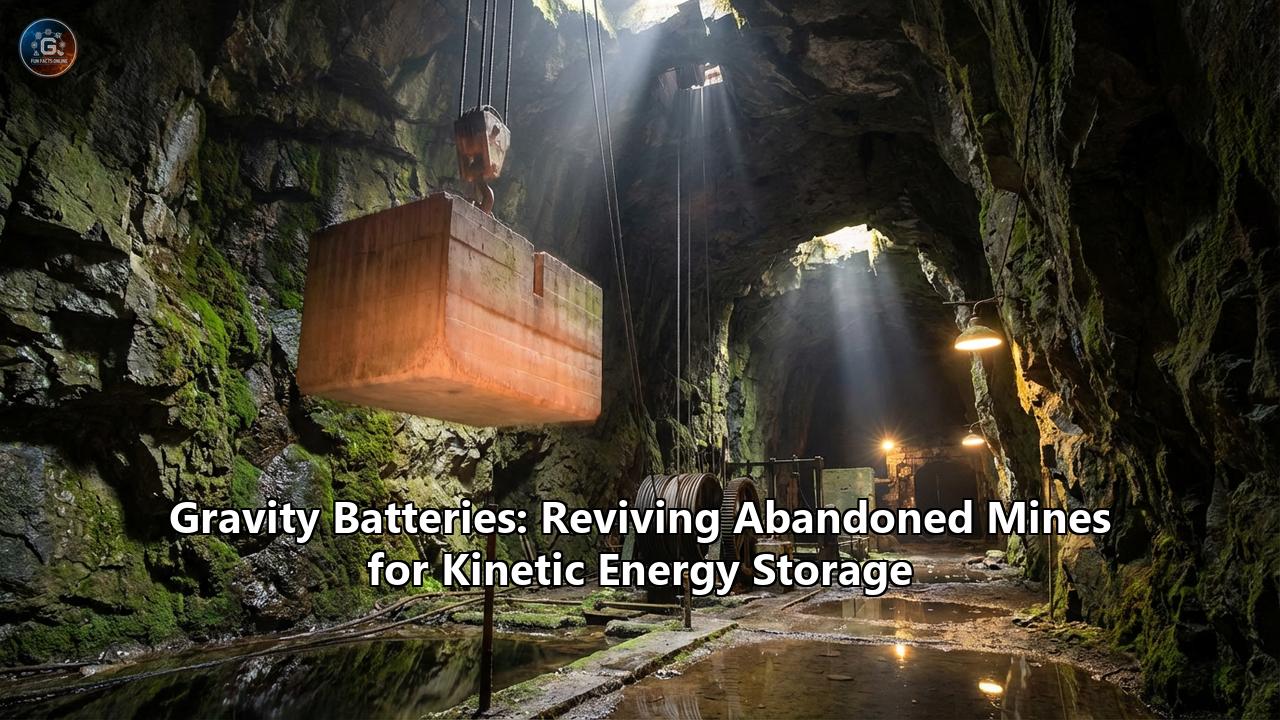

Enter the sleeping giants of the industrial age: abandoned mines.

Deep beneath the earth, in the scarred and hollowed-out remains of the coal and metal industries, a revolution is quietly taking shape. It is a solution that requires no new exotic materials, no chemical factories, and no complex supply chains. It relies on a force as old as the universe itself: Gravity.

This is the story of how we are turning the liabilities of our carbon-heavy past into the assets of our green future. This is the rise of the Gravity Battery.

Part I: The Physics of Falling

To understand why a hole in the ground is worth billions of dollars, we must first revisit high school physics. The concept of a gravity battery is elegantly simple, relying on the equation for gravitational potential energy:

$$PE = m \times g \times h$$

Where:

- $m$ is mass (the heavier, the better).

- $g$ is the acceleration due to gravity (constant).

- $h$ is height (the vertical distance).

When you lift a heavy object against the pull of gravity, you are "charging" the battery. You are investing energy into that object, storing it as potential energy. As long as the object stays suspended, that energy is trapped, waiting. When you need electricity, you let the object fall. As it descends, gravity pulls it down, spinning a winch, which turns a generator, pushing electrons back into the grid.

The Oldest Battery in the World

This is not a new idea. In fact, it is currently the world’s largest form of energy storage. It is called Pumped Storage Hydropower (PSH).

For nearly a century, we have been pumping water from a lower reservoir to an upper reservoir when electricity is cheap (charging) and letting it flow back down through turbines when electricity is expensive (discharging). Pumped hydro accounts for over 90% of the world's grid-scale energy storage.

However, pumped hydro has a fatal flaw: it requires mountains. You need a specific topography—two massive reservoirs separated by significant elevation—to make it work. It also requires flooding vast valleys, which faces immense environmental opposition today. You cannot build pumped hydro in the middle of a flat city or a dry desert.

But you can find a vertical drop in places where mountains don't exist. You just have to look down.

Part II: The Buried Treasure

The world is honeycombed with mines. There are millions of abandoned shafts across the globe—relics of the hunger for coal, copper, zinc, and gold. In the United States alone, there are an estimated 550,000 abandoned mines.

For decades, these sites have been viewed as liabilities. They are environmental hazards, leaking acid mine drainage into water tables, leaking methane into the atmosphere, and representing the economic decay of "rust belt" communities left behind by the energy transition.

Gravity battery companies look at these dark, damp shafts and see something else: Pre-built Skyscrapers.

A deep mine shaft is essentially a pre-constructed vertical tower. It offers the "$h$" (height) in our equation without the cost of building a concrete tower.

- Infrastructure: The shafts are already dug. They are reinforced with concrete or steel.

- Grid Connection: Mines are heavy industrial sites. They already have massive power lines running to them, capable of handling megawatts of load.

- Depth: Some mines go down 2,000 meters or more. The deeper the drop, the more energy you can store.

By retrofitting these shafts, we can create "Solid State" pumped hydro. Instead of water, we use heavy weights—iron, concrete, or compacted sand. We don't need dams, we don't need lakes, and we don't need to flood valleys.

Part III: The Players and the Technology

Several pioneering companies are currently racing to commercialize this technology, each with a slightly different engineering approach to "dropping rocks."

1. Gravitricity: The Winch Masters

Based in Edinburgh, Scotland, Gravitricity is perhaps the most prominent player in the shaft-based gravity storage game. Their technology, dubbed "GraviStore," looks like a high-tech elevator system.

How it Works:Imagine a massive winch system sitting over the mouth of a mine shaft. Suspended by steel cables are enormous weights—potentially up to 12,000 tonnes total—made of iron or high-density composite materials.

- Charge: Electric winches lift the weights to the top of the shaft.

- Discharge: The weights are lowered. The motors become generators.

- Speed: Gravitricity’s system can go from zero to full power in less than one second. This makes it incredibly valuable for "frequency response"—stabilizing the grid when supply and demand fluctuate slightly 50 times a second.

- Longevity: Unlike lithium-ion batteries, which lose capacity after a few thousand cycles, a winch system is mechanical. With maintenance (replacing cables, greasing gears), it can last 50 years with zero degradation.

In 2024 and 2025, the eyes of the energy world turned to Pyhäjärvi, Finland. The Pyhäsalmi Mine is Europe’s deepest metal mine, plunging 1,444 meters (nearly a mile) into the Earth. It was once a thriving copper and zinc mine, employing hundreds. When mining operations ceased in 2022, the town faced economic collapse.

Gravitricity stepped in to repurpose the mine's 530-meter auxiliary shaft. They are deploying a 2MW prototype. It serves as a proof-of-concept that will likely pave the way for full-scale commercialization. This project is symbolic: a site that once extracted the earth's resources is now being used to heal the earth's atmosphere.

2. Green Gravity: The Australian Heavyweights

On the other side of the world, Australia is grappling with the retirement of its massive coal industry. Green Gravity, an Australian startup, is partnering with major mining conglomerates like Glencore and Wollongong Resources.

The Innovation:Green Gravity uses a slightly different approach tailored to the vast number of coal shafts in Australia. Their system often utilizes multiple smaller weights rather than one giant block. This allows for continuous power generation—as one weight reaches the bottom, another is already dropping.

The Russell Vale Project:In late 2025, Green Gravity advanced a binding agreement to trial their technology at the Russell Vale mine in New South Wales. This former coal mine will host a "Gravity Lab," testing a system that simulates commercial-scale operations.

- The Goal: To revitalize the Illawarra region, transforming it from a coal hub to a renewable energy storage hub.

- The Scale: They have identified a pipeline of over 75 shafts capable of storing 10 Gigawatt-hours (GWh) of energy. To put that in perspective, 10 GWh could power hundreds of thousands of homes through the night.

3. IIASA and UGES: The Sand Solution

The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) has proposed a variation called Underground Gravity Energy Storage (UGES). Instead of solid metal weights, they propose using sand.

The Mechanism:- Storage: Large containers of sand are lowered into the mine to generate electricity.

- Retrieval: When energy is cheap, electric motors lift the sand back to the surface (or an upper storage chamber).

- Why Sand? It is cheap, abundant, and fluid. It can be moved on conveyors. The IIASA study estimates that UGES has a global potential of 7 to 70 TWh.

Part IV: The Economic & Social Case

Why choose gravity over batteries? The argument is not just technical; it is economic and social.

1. The Levelized Cost of Storage (LCOS)

Lithium-ion batteries are getting cheaper, but they have a high "marginal cost of capacity." If you want to store energy for 10 hours instead of 4, you need to buy 2.5 times more batteries.

With gravity storage, if you want to store more energy, you just need a deeper hole or heavier weights. The "engine" (the winch and generator) stays the same. This makes gravity storage potentially much cheaper for Long Duration Energy Storage (LDES)—storage that lasts 8, 12, or 24 hours.

2. The "Just Transition"

This is the most compelling narrative for politicians and local communities.

When a mine closes, a town dies. The jobs vanish, the tax base crumbles, and the young people leave.

Gravity batteries offer a lifeline. The skills required to maintain a gravity battery—operating winches, inspecting shafts, managing heavy machinery, high-voltage electrical work—are almost identical to the skills possessed by miners.

- Pyhäjärvi, Finland: The town is actively rebranding itself as a technology hub, saving jobs that were lost when the zinc ran out.

- Illawarra, Australia: Coal miners can transition to "energy miners" without leaving their hometowns.

3. Supply Chain Sovereignty

Lithium batteries require cobalt from the DRC, nickel from Indonesia, and lithium from South America, processed largely in China.

Gravity batteries require Steel and Concrete. Every country has steel and concrete. They can be built with local supply chains, insulating national grids from geopolitical trade wars.

Part V: The Challenges and Risks

If this is so perfect, why haven't we done it yet? There are significant engineering hurdles.

1. Geological Stability:Mines are abandoned for a reason. They can be unstable. Seismic activity or rock bursts could jam a weight in a shaft or collapse the infrastructure. Rigorous geological surveying is required to ensure the shaft can withstand decades of heavy lifting.

2. The "Piston Effect":Dropping a massive weight down a tight shaft creates aerodynamic drag—like a piston in an engine. The air pressure below the weight increases, resisting the drop. Sophisticated airflow management and venting systems are needed to prevent this from reducing efficiency.

3. Water Management:Deep mines flood. To operate a dry weight system, you must constantly pump water out. This consumes energy, potentially lowering the "Round Trip Efficiency" (RTE) of the system.

- Counter-solution: Some designs propose using the water itself (Underground Pumped Hydro) or designing weights that are neutrally buoyant or aerodynamic enough to move through water, though this adds drag.

The steel cables holding these multi-tonne weights are under immense stress. They are being wound and unwound constantly. Metal fatigue is a real risk. If a cable snaps, a 50-tonne weight plummeting 1,000 meters is effectively a bomb. Redundancy and advanced material science (like synthetic Kevlar-based ropes) are critical areas of research.

Part VI: The Future Outlook (2025-2040)

We are currently in the "Prototype Phase" (2023-2026). Projects like Pyhäsalmi and Russell Vale are the proving grounds.

The next phase is "Commercial Deployment" (2027-2035). As the first generation of wind and solar farms reach terawatt scales, the demand for storage will outstrip lithium production capacity. This is when gravity storage will shine.

Integration with Hydrogen?There is also talk of hybrid systems. Mines could produce Green Hydrogen via electrolysis when there is excess power, store the hydrogen in lateral tunnels, and use the vertical shafts for gravity batteries. The mine becomes a total energy park.

The 70 Terawatt-Hour PrizeThe IIASA study's figure of 70 TWh is staggering. The entire world consumes about 25 TWh of electricity per day. Theoretically, repurposed mines could store enough energy to power the entire planet for days at a time. Even capturing 1% of this potential would revolutionize the global grid.

Conclusion

We have spent centuries digging into the earth to extract power. We burned the coal and melted the ore, building a civilization that is now threatened by the very emissions that fueled its rise.

There is a poetic justice in the Gravity Battery. We are returning to the scenes of the crime—the scarred landscapes and hollowed mountains—and turning them into the engines of our redemption. The dark, abandoned shafts that once brought up the carbon that warmed the world will soon be bringing up the clean power that saves it.

The technology is ready. The infrastructure is waiting. The only thing left to do is let gravity take over.

Reference:

- https://m-mtoday.com/news/europes-deepest-mine-to-become-colossal-gravity-battery/

- https://www.innovationnewsnetwork.com/abandoned-mines-could-soon-become-energy-storage-hubs/28825/

- https://planetark.com/newsroom/news/abandoned-mine-in-finland-will-be-powered-up-again-to-store-renewable-energy

- https://www.ees-eu.com/post/unleashing-the-potential-how-abandoned-mines-could-revolutionize-global-energy-storage

- https://retrofuturista.com/pyhasalmi-mine-adopts-gravity-battery-a-step-towards-cleaner-energy/

- https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1960432

- https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/energy/a42613216/scientists-turn-abandoned-mines-into-gravity-batteries/

- https://qazaqgreen.com/en/news/world/1758/

- https://www.ess-news.com/2024/10/16/green-gravitys-long-duration-storage-solution-attracts-6m/

- https://www.mining.com/first-commercial-gravity-storage-for-energy-planned-in-finnish-mine/

- https://eepower.com/news/green-gravity-tests-energy-storage-in-australian-mine-shaft/

- https://renewablesnow.com/news/green-gravity-to-trial-gravitational-energy-storage-in-nsw-mine-1281923/

- https://www.azomining.com/Article.aspx?ArticleID=1750

- https://www.techspot.com/news/97306-gravity-batteries-abandoned-mines-could-power-whole-planet.html

- https://2024.minexeurope.com/2024/05/15/gravitricity-to-develop-underground-gravity-energy-storage-projects-in-europe/

- https://www.theregister.com/2024/02/08/europe_deepest_mine_battery/

- https://renewablesnow.com/news/gravitricity-plans-2-mw-gravity-energy-store-at-finnish-mine-847637/

- https://www.energy-storage.news/green-gravity-glencore-to-explore-2gwh-energy-storage-project-at-copper-mine-in-mount-isa-australia/

- https://www.pv-magazine.com/2025/09/19/gravitational-energy-storage-trials-set-for-decommissioned-mine-in-australia/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330997953_Gravity_energy_storage_with_suspended_weights_for_abandoned_mine_shafts

- https://iiasa.ac.at/news/jan-2023/turning-abandoned-mines-into-batteries

- https://www.21stcentech.com/abandoned-shafts-renewable-energy-storage/