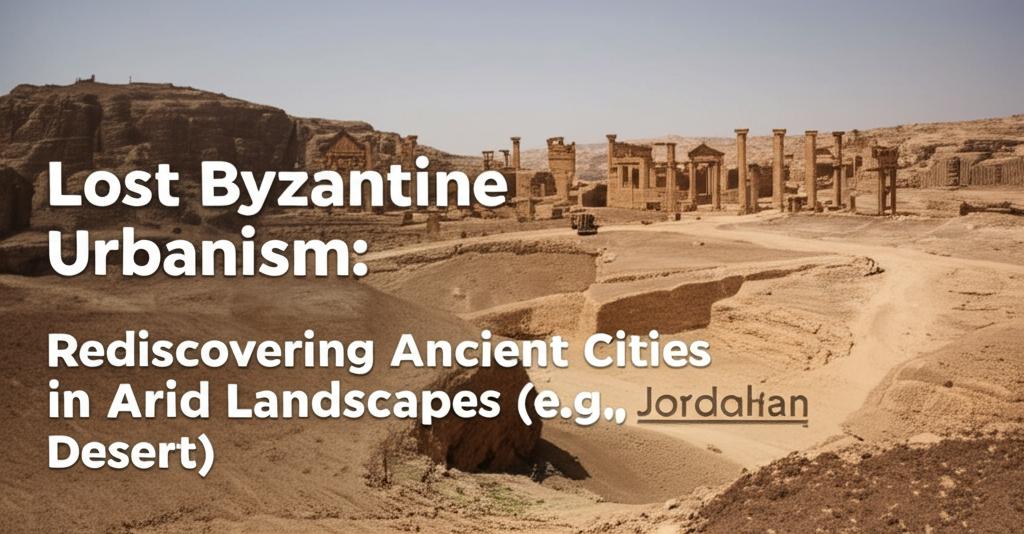

The desert sands have long whispered tales of forgotten empires and bustling metropolises swallowed by time. In the arid landscapes of regions like modern-day Jordan, a new chapter in Byzantine history is being meticulously unearthed, revealing sophisticated urban centers that thrived against the odds. These rediscoveries are painting a vivid picture of life on the eastern fringes of an empire renowned for its grandeur and resilience, showcasing how ingenuity and adaptation allowed complex societies to flourish where today we see only stark, dry beauty.

Between the 4th and 7th centuries CE, during the Byzantine era, what is now Jordan underwent a profound transformation. Formerly the Roman Provincia Arabia Pétrea, the region became a significant part of the Eastern Roman Empire. With Christianity as the state religion, the urban landscape experienced a new wave of development. Cities that had already prospered under Roman rule, like Gerasa (Jerash), Madaba, Petra, and Umm ar-Rasas, were infused with new life and purpose. The era was marked by a boom in population and a healthy network of trade and economic activity that brought overall prosperity.

Whispers from the Sands: Unearthing Lost CitiesOne of the most exciting aspects of this ongoing research is the rediscovery of cities once known only from historical texts or ancient maps. Recently, archaeologists believe they have found the lost Byzantine city of Tharais in southern Jordan. Depicted on the famed 6th-century Madaba Mosaic Map – the oldest surviving cartographic representation of the Middle East – Tharais's exact location had been a puzzle for centuries. Through careful re-examination of historical documents, inscriptions, and extensive field surveys near the modern town of El-'Iraq, compelling evidence has emerged. The discovery of ceramics, Greek and Latin funerary inscriptions, mosaic fragments, and, crucially, the ruins of a Byzantine church and other structures that seem to align with the Madaba Map's depiction, strongly suggest this is the long-lost settlement. Tharais is thought to have been an important religious and trading hub along the Roman and Byzantine road network, connecting Zoar (modern Ghor es-Safi) to central Jordan. Its rediscovery highlights the vital role such settlements played as agricultural villages, sacred sites, and commercial rest stops.

Engineering Life in the Drylands: Water, Agriculture, and TradeThe success of these Byzantine desert cities hinged on remarkable feats of engineering, particularly in water management. In a semi-arid to arid climate, securing a reliable water supply was paramount. Archaeological evidence reveals sophisticated systems for harvesting and storing rainwater. At sites like Umm el-Jimal, a Byzantine city in northern Jordan, inhabitants constructed deflection dams, canals, and numerous reservoirs. Cisterns, both open and underground, were ubiquitous, ensuring water for domestic use, agriculture, and even for garrisons stationed in fortresses. Clay pipes were used to channel water over distances, sometimes incorporating settling basins to remove silt before the water reached storage tanks or large pools.

This mastery over water resources enabled surprisingly productive agriculture. Archaeobotanical studies have confirmed local agricultural activity, with the discovery of cereal grains, legumes, and crop by-products in arid regions where such cultivation is absent today. The Hawran plains, for instance, were a major source of wheat and barley, while spring-fed valleys were planted with vines, olives, fruits, and nuts. This agricultural output was crucial not only for sustaining the local population but also for supporting the significant Roman and Byzantine military presence in the region. These findings suggest that ancient water management techniques were perhaps more advanced than previously acknowledged, allowing communities to effectively 'green the desert'.

Trade was the lifeblood of these urban centers. Jordan's strategic location, at the crossroads of ancient trade routes, facilitated a vibrant economy. The King's Highway, a route in continuous use since at least the 8th century BCE, connected Arabia, the Fertile Crescent, the Red Sea, and Egypt. During the Roman period, Emperor Trajan upgraded this road, renaming it the Via Nova Traiana. In the Byzantine era, it was traversed by Christian pilgrims heading to holy sites, as well as by caravans carrying valuable goods. Spices and incense from Arabia, silk from China, and goods from India flowed through these routes, with cities like Petra and Aila (modern Aqaba) serving as key commercial hubs. Aila, a port on the Red Sea, was particularly important for maritime trade, connecting the Byzantine Empire to regions as far as Ethiopia and India. The discovery of amphorae from Aqaba throughout the Red Sea region and even Axumite coins in Jerusalem attest to these extensive trade links.

Faith and Artistry Carved in Stone and MosaicThe Christianization of the Empire under Constantine I led to a radical change in Jordan's urban landscape, with the construction of numerous churches, monasteries, and pilgrimage centers. Byzantine architecture in Jordan is characterized by basilicas with long naves, semicircular apses facing east, and parallel rows of columns. Sites like Jerash boast the Cathedral of St. Theodore and other churches with stunning mosaic floors and religious inscriptions.

Umm ar-Rasas, an ancient Roman fortress repurposed by the Byzantines, is particularly notable, containing over a dozen churches. The Church of St. Stephen here features extraordinary mosaic floors depicting various Byzantine cities, underscoring the interconnectedness of the imperial territories. Mount Nebo, traditionally associated with Moses, became a major pilgrimage site, its church adorned with mosaics depicting pastoral scenes, hunting, and daily life, beautifully fusing sacred and secular art.

The art of mosaic reached a pinnacle during this period. The Madaba Map itself is a testament to this skill. Churches in Jerash, like that of Saints Cosmas and Damian, feature vibrant mosaic floors with diverse motifs, including scenes from daily life, animals, and intricate floral and geometric designs. Even Petra, famed for its earlier Nabataean heritage, has yielded Byzantine-era mosaics with exotic animals and human figures, showcasing the continuity of this art form.

The Fading Light: Decline and AbandonmentDespite their ingenuity and prosperity, these Byzantine desert cities eventually faced decline and abandonment. The reasons are complex and likely interconnected. A series of disasters, including major earthquakes in the 5th and 6th centuries and the devastating plague of 541/542, undoubtedly contributed to societal decline. Some research points to urban collapse in regions like the Negev Desert occurring even before the Islamic conquests of the 7th century. The demise of the intensive agricultural systems in these marginal arid lands in the mid-sixth century may have been linked to wider urban crises, climatic shifts (though the exact role of climate change is still debated), or a dependence on external markets or imperial subsidies that waned. By the 7th century, the rise of Islam and the subsequent Arab conquests led to a shift in political and economic power, and many Byzantine settlements gradually faded or were transformed.

Echoes for the Future: Why These Discoveries MatterThe rediscovery and study of these lost Byzantine cities offer more than just a glimpse into a bygone era. They provide invaluable insights into human adaptability, urban development in challenging environments, and the complex interplay of culture, religion, trade, and climate in shaping civilizations. The advanced water harvesting and agricultural techniques employed by these ancient desert dwellers hold potential lessons for sustainable living in arid regions today.

As archaeologists continue to sift through the sands, piecing together the stories of these remarkable urban centers, our understanding of the Byzantine Empire's reach and resilience, particularly on its arid frontiers, becomes richer and more nuanced. These once-lost cities are a powerful reminder that even in the harshest landscapes, human ingenuity and a well-organized society can create oases of vibrant life, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire and inform centuries later. The desert, it seems, still has many more secrets to reveal about the enduring spirit of Byzantine urbanism.