The mists of the Atherton Tablelands have always guarded their secrets with a jealous, damp embrace. Here, in the high-altitude rainforests of Far North Queensland, the ancient Gondwanan heritage of Australia clings to the peaks, separated from the lowland tropics by steep escarpments and a veil of clouds. For decades, entomologists and locals alike whispered of "giants" in the canopy—spectral shapes that moved against the wind, branches that walked. But it was only recently, in the mid-2020s, that the true scale of these phantoms was revealed.

The scientific world now knows it as Acrophylla alta, but to the locals and the wider public, it has earned a far more evocative name: The Atherton Titan.

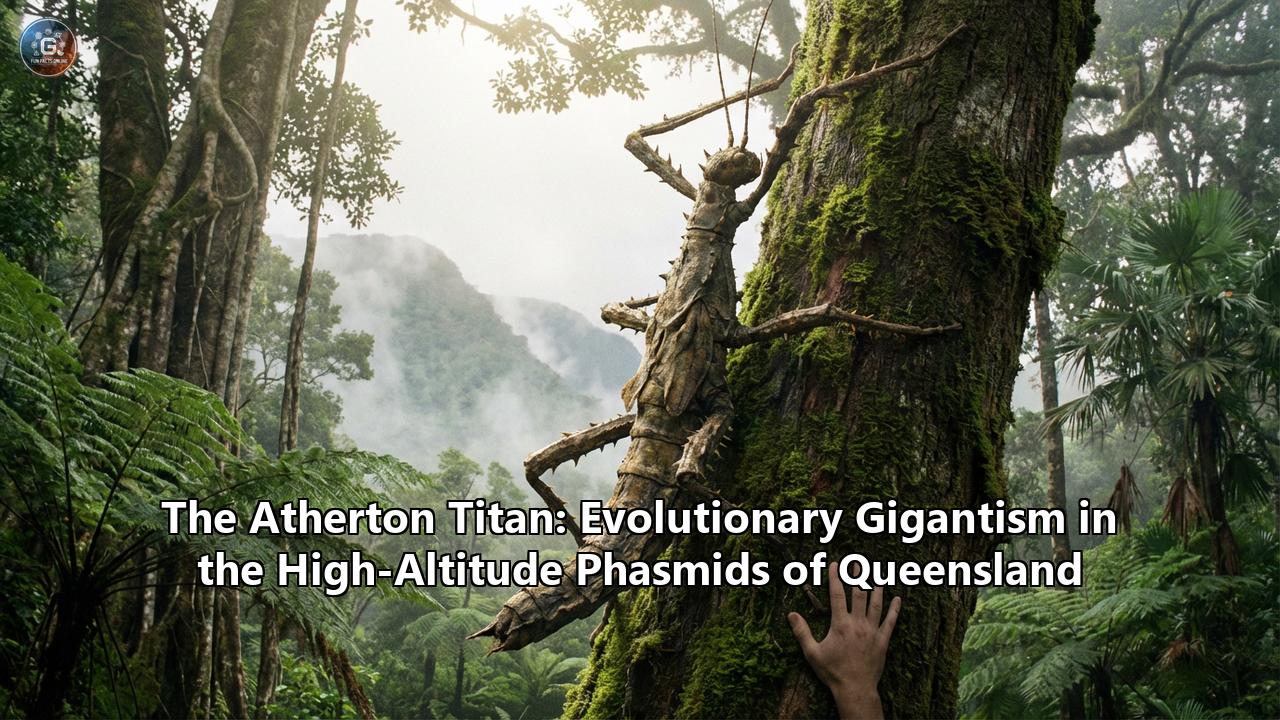

Weighing in at a staggering 44 grams—the weight of a golf ball, yet distributed across a slender, armored frame nearly half a meter long—the Atherton Titan is not merely a curiosity; it is a biological marvel. It challenges our understanding of insect physiology, reignites debates on evolutionary gigantism, and serves as a living totem for the fragile "sky island" ecosystems of Queensland. This is the story of the Titan, the evolutionary forces that forged it, and the high-altitude world it rules.

Part I: The Sky Islands of the North

To understand the Titan, one must first understand its fortress. The Atherton Tablelands are a plateau in the Great Dividing Range, a region where the landscape rises abruptly from the coastal plains to elevations exceeding 1,000 meters. These are not merely mountains; they are ecological islands floating in a sea of warmer, drier air.

Biologists refer to these isolated high-altitude habitats as "Sky Islands." Just as the Galapagos Islands isolated species in the ocean, allowing them to follow unique evolutionary trajectories, the peaks of the Wet Tropics isolate cold-adapted species in the sky. The climate here is distinct: cooler, perpetually wet, and often shrouded in cloud cover (or "occult precipitation") that strips moisture from the passing trade winds.

It is a world of suspended moss gardens, ancient Antarctic beech relatives, and epiphytes that burden every available branch. For millions of years, as the Australian continent drifted north and dried out, these peaks remained refugia—lifeboats of the ancient rainforest that once covered the entire continent. In this isolation, the evolutionary pressure cooker went to work.

Isolation is a key ingredient for oddity. On islands, small animals often evolve to be large (island gigantism) to exploit unfilled niches or because there are fewer predators. Conversely, large animals often shrink (island dwarfism) due to limited resources. The Atherton Tablelands present a complex variation of this theme. The insects here are not trapped on a rock in the ocean, but they are trapped by temperature. Venture too far down the mountain, and the heat becomes lethal for a species adapted to the cool mists.

In this high-altitude cage, the ancestors of Acrophylla alta found themselves with a unique set of constraints and opportunities. The result was a slow, measured slide toward gigantism that would eventually produce the heaviest insect in Australia.

Part II: The Titan Revealed

The discovery of Acrophylla alta is a testament to the persistence of citizen science and the elusive nature of the canopy. For years, the record for Australia's longest insect was held by Ctenomorpha gargantua, a lowland cousin that can reach over 50 centimeters in length but remains relatively slender. The Titan is different. It is a creature of mass.

The Discovery

The species was formally described in 2025 by researchers including Professor Angus Emmott and Ross Coupland, following a breadcrumb trail of social media photos and serendipitous storm events. Unlike ground-dwelling beetles, the Titan is a canopy obligate. It spends its entire life 20 to 50 meters above the forest floor, in the swaying crown of the rainforest.

Finding one "in situ" is nearly impossible. They are masters of crypsis—the art of remaining unseen. It usually takes a cyclone, a violent storm, or a clumsy bird to dislodge a female from her perch. When they hit the ground, they are often stunned, offering a rare glimpse to the lucky observer. It was one such specimen—a female found dazed but alive near Millaa Millaa—that confirmed the rumors. She didn't just look like a stick; she looked like a branch, thick, heavy, and formidable.

Morphology of a Giant

The female Atherton Titan is a tank among phasmids. While males are slender and capable of flight—necessary to patrol the vast canopy for mates—the females have sacrificed flight for size and fecundity.

- Weight: At 44 grams, the female Titan rivals the weight of small birds. This mass allows for a massive egg load (more on that later) and greater thermal inertia.

- Length: Body lengths exceed 40 centimeters, with legs outstretched pushing the total footprint even larger.

- Armament: The Titan is not defenseless. Her legs are lined with serrated spines. When threatened, she does not merely hide; she can lash out with her hind legs, using the spines to pinch or deter predators like possums or currawongs.

- Wings: The females possess wings, but they are vestigial for flight. They serve a different purpose: display. Flash colors hidden beneath the primary wings can startle predators, a behavior known as deimatic display.

The difference between the sexes is stark. The male is a sleek, long-distance traveler, evolved to traverse the dangerous gaps between trees. The female is a sedentary fortress, an egg-producing factory built to withstand the elements.

Part III: The Evolutionary Drivers of Gigantism

Why get so big? In the animal kingdom, size is expensive. It requires more food, takes longer to reach maturity, and makes you a juicy target for predators. Yet, the Atherton Titan embraced gigantism. Several evolutionary theories converge to explain this phenomenon in the Queensland highlands.

1. The Cool Climate Hypothesis (Bergmann’s Rule variant)

Classically, Bergmann's Rule states that warm-blooded animals get larger in colder climates to conserve heat. However, for ectotherms (cold-blooded animals) like insects, the relationship is complex. In the cool, mist-shrouded peaks of the Tablelands, being larger offers "thermal inertia." A larger body mass cools down more slowly than a small one.

Nights in the Atherton highlands can be surprisingly chilly. A tiny stick insect might become torpid and unable to move or feed until late morning. The massive Titan, retaining some heat from the day or generating it through metabolic processes, may gain a few extra hours of activity, allowing it to feed and process toxins from eucalyptus leaves more efficiently.

2. The Fecundity Advantage

The most compelling driver for the female's size is reproductive output. In the harsh, vertical world of the rainforest canopy, the attrition rate for eggs is astronomical. Eggs are dropped from 40 meters up; they bounce off leaves, get eaten by ground foraging marsupials, or succumb to fungal rot.

To ensure the survival of the next generation, the female Titan effectively becomes a maximized egg vessel. Her heavy abdomen is packed with hundreds of large, nutrient-rich eggs. By sacrificing flight, she removes the weight limit imposed by aerodynamics, allowing her to grow as large as her food source can support.

3. Predation Release and Canopy dominance

In many ecosystems, insects are kept small by the intense pressure of nimble, sight-based predators like insectivorous birds. However, the high canopy of the Cloud Forest is a difficult hunting ground. The density of the foliage and the constant movement of the wind make spotting a stationary stick insect incredibly difficult.

Furthermore, the sheer size of the Titan may push it out of the prey bracket for smaller birds. A thornbill or a scrubwren cannot tackle a 44-gram spiny branch. Only larger predators like the Victoria's Riflebird or possums pose a threat, and against them, the Titan's camouflage and spiny legs are a specific, evolved defense.

Part IV: The Life Cycle of the Titan

The life of an Atherton Titan is a slow, vertical journey. It begins on the forest floor, a place the adult female will never voluntarily visit.

The Drop

The female Titan does not carefully place her eggs. She acts as a botanical bomber, flicking her eggs from the canopy to rain down onto the leaf litter below. The eggs of Acrophylla alta are distinct—resembling specific plant seeds found in the region. This is likely a form of myrmecochory (ant mimicry). The eggs have a capitulum—a fatty handle—that encourages ants to carry them into their nests. Safe underground, the eggs are protected from fire and parasites until they hatch.

The Ascent

When the nymph emerges, it is a miniature, fragile replica of the adult. It faces the most dangerous moment of its life: the ascent. It must climb 30 or 40 meters of trunk, navigating a gauntlet of spiders, geckos, and centipedes, to reach the fresh foliage of the canopy.

Those that survive the climb settle into a rhythm of eating and molting. As they grow, they shed their exoskeletons, hanging precariously from leaves. For a creature as heavy as the Titan, the final molt is a perilous engineering feat. Gravity is an enemy; if she falls during the molt, her soft body will be crushed or deformed.

The Diet

The Titan is a specialist feeder, browsing on specific high-altitude rainforest trees, including species of Eucalyptus and Syzygium (Lilly Pilly). The leaves here are tough and often loaded with chemical deterrents. The Titan’s large size houses a substantial gut, acting as a fermentation chamber to break down these tough fibers and neutralize toxins.

Part V: A Fragile Giant in a Warming World

The discovery of the Atherton Titan has sent ripples of excitement through the scientific community, but it is excitement tempered with dread. The Titan is a creature of the cold clouds. It is, in ecological terms, trapped on an escalator that is running out of stairs.

As global temperatures rise, the "cloud layer" of the tropical mountains is lifting. The cool, misty zone that the Titan requires is moving higher up the mountain. But the mountains of Queensland are not infinite. Eventually, the habitat will be pushed off the peak.

Research indicates that high-altitude endemics are among the most vulnerable species to climate change. If the average temperature of the Tablelands rises by even two degrees, the metabolic advantage of the Titan's size may turn into a liability, and the distinct vegetation it relies on may be outcompeted by lowland species moving up.

The Titan has thus become a flagship species for the conservation of the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area. Its presence indicates a healthy, complex canopy structure and a functional high-altitude climate. Protecting the Titan means protecting the water towers of the north—the forests that capture the rain and feed the rivers of the region.

Part VI: The Human Connection

There is something deeply humbling about the Atherton Titan. In an age where we believe we have mapped every corner of the globe via satellite, where we feel we have cataloged the natural world, a creature the size of a forearm was living undetected in our backyard.

It reminds us that the rainforest is not just a collection of trees, but a three-dimensional kingdom where humanity is largely confined to the basement. The canopy remains a "biological frontier," accessible only to those with the patience to watch, or the luck to be there when the giants fall.

For the people of the Atherton Tablelands, the Titan is a new source of pride—a gentle giant of the mist that embodies the mystery and majesty of their unique home. It serves as a reminder to look up, to tread lightly, and to respect the giants that walk silently in the clouds above.

Reference:

- https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.06.09.495408v3.full.pdf

- https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/news/2014/03/biggest-gargantuan-stick-insect-found/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fzPHLeOIO2w

- https://blog.qm.qld.gov.au/2025/08/01/meet-the-giants-the-heaviest-insects-in-queensland-museums-collection/

- https://www.miragenews.com/supersized-stick-insect-discovered-in-wet-1507510/

- https://australian.museum/aap/naming-newly-discovered-giant-insect-a-sticking-point/

- https://shop.minibeastwildlife.com.au/content/Minibeast%20Wildlife%20Care%20Guide%20-%20Gargantuan%20Stick%20Insect%20-%20Ctenomorpha%20gargantua.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ctenomorpha_gargantua

- https://bunyipco.blogspot.com/2020/12/australias-and-probably-worlds-longest.html

- https://blog.qm.qld.gov.au/2011/06/01/fantastic-phasmids/

- https://www.minibeastwildlife.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Minibeast-Wildlife-Care-Guide-Peppermint-Stick-Insect-Megacrania-batesii.pdf