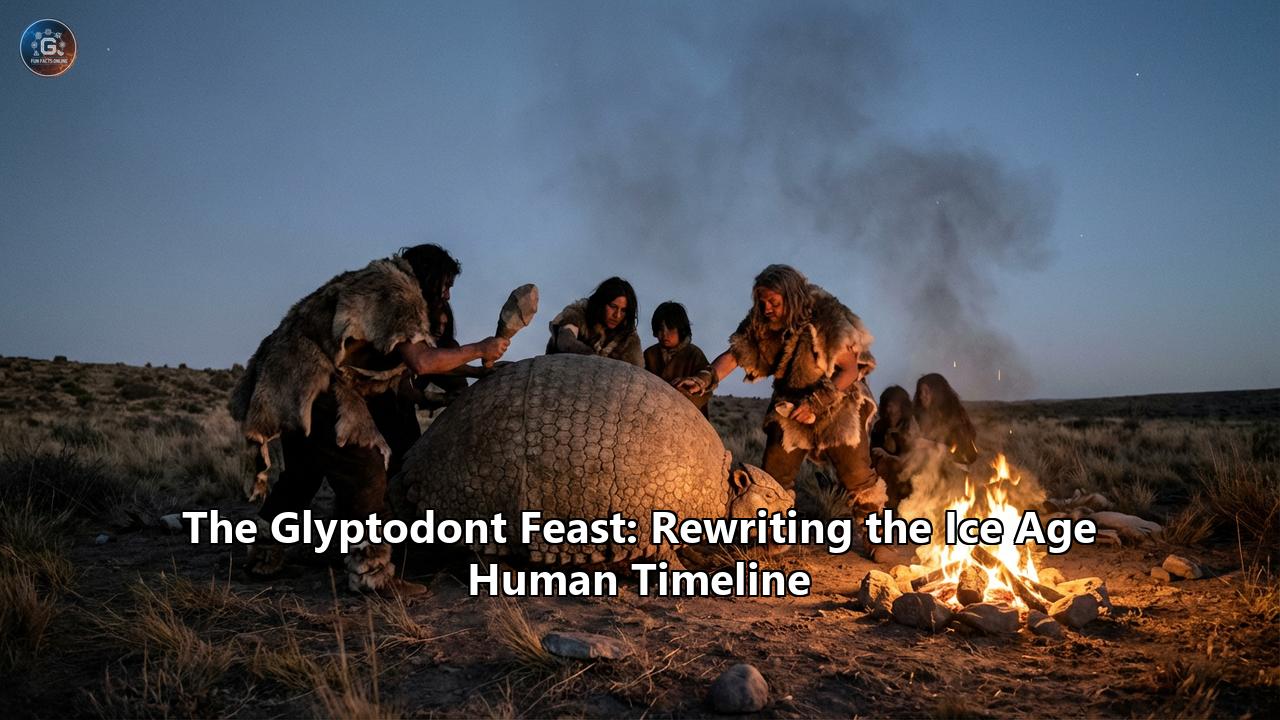

It was a cold, arid afternoon on the banks of what we now call the Reconquista River, just outside modern-day Buenos Aires. The wind whipped across the vast steppes of the Pampas, carrying the scent of dry grass and the distant, heavy musk of megafauna. The year was approximately 19,000 B.C.E.—though the small band of hunter-gatherers huddled over the massive carcass didn't know the date. They only knew hunger, and the immense stroke of fortune lying before them.

Lying in the mud was a Neosclerocalyptus, a biological tank of an animal, a relative of the armadillo but built on a scale that defies modern imagination. It was dead. With precise, practiced movements, a human hand gripped a sharp flake of stone. The tool sliced through the thick hide near the pelvis, scraping against bone with a sound that would echo across twenty-one millennia.

That sound—the scrape of stone on bone—has recently been heard by scientists in a laboratory in Argentina. And it has shattered our understanding of when humans arrived in the Americas.

This is the story of the Glyptodont Feast, a discovery that has rewritten the timeline of human history, pushing the clock back by thousands of years and forcing us to discard the textbooks on the Ice Age peopling of the New World.

Part I: The Discovery in the Riverbank

For decades, the story of the Americas was simple. We were told that humans crossed the Bering Land Bridge from Siberia to Alaska around 13,000 years ago, following the retreat of the massive ice sheets. These people, known as the Clovis culture, were the first pioneers, spreading rapidly south with their distinctive fluted spear points.

But science is rarely simple, and the earth has a habit of keeping secrets that don't fit our clean narratives.

In 2024, a team of Argentine anthropologists and paleontologists, led by Dr. Mariano Del Papa from the National University of La Plata, published a bombshell study in the journal PLOS ONE. The subject of their study was a fossil found on the banks of the Reconquista River, a tributary that winds through the bustle of the Buenos Aires metropolitan area.

The fossil itself was not new to science; glyptodont remains are relatively common in the rich soils of the Pampas. These armored giants roamed South America for millions of years. But this particular specimen, a Neosclerocalyptus, had something unusual on its bones.

When the researchers cleaned the fossilized pelvis and vertebrae, they noticed marks. Not the random scratches of scavenging wolves or the gnawing of ancient rodents. These were linear, distinct, and purposeful.

The Marks of IntentionTo the untrained eye, a scratch on a bone is just a scratch. To a taphonomist—an expert in what happens to an organism after death—a scratch is a crime scene clue.

The team subjected the bones to rigorous analysis, using 3D scanning and statistical modeling to map the topography of the marks. They looked at the cross-sections of the cuts. Carnivore teeth typically leave U-shaped grooves, rounded at the bottom. Natural abrasion from tumbling in a river leaves chaotic, shallow scratching.

These marks were V-shaped. They were deep, straight, and possessed the tell-tale "shoulder" created by the edge of a stone tool slicing through resistant tissue. Furthermore, they weren't random. They were clustered in specific anatomical zones: the pelvis, the tail, and the caudal vertebrae.

Why does this matter? Because no wolf or saber-toothed cat knows anatomy like a butcher does. These areas are where the massive muscle insertions are located. The cuts were evidence of a systematic dismantling of the animal, specifically targeting the dense, calorie-rich meat of the hindquarters and the tail.

This was not a kill site; it was a butchery floor.

Part II: The Dating Shock

If finding cut marks on a glyptodont was the spark, the radiocarbon dating was the explosion.

The "Clovis First" dogma had long held that humans didn't reach the southern cone of South America until perhaps 12,000 or 13,000 years ago. Even the most aggressive "Pre-Clovis" theories usually capped the date at around 16,000 years ago (based on sites like Monte Verde in Chile).

The researchers took a fragment of the pelvic bone and sent it for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dating. The results came back, and likely, the researchers had to check them twice.

21,000 Years Old.The date was unequivocal. The carbon isotopes indicated that this animal died—and was butchered—around 21,000 years before the present.

This date lands squarely in the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), the height of the Ice Age, when the global ice sheets were at their thickest and sea levels were at their lowest. It implies that humans were not just present in South America 6,000 years earlier than previously thought, but that they were thriving in a cold, semi-arid environment, successfully hunting or scavenging megafauna long before the ice corridors in North America were supposed to be open.

The implications are staggering. If people were butchering armadillos in Argentina 21,000 years ago, they must have crossed into the Americas thousands of years prior to that. They likely traveled down the Pacific coast, navigating a landscape of glaciers and kelp forests, essentially "island hopping" their way south while the interior of North America was an impassable wall of ice.

Part III: The Victim – Neosclerocalyptus

To understand the magnitude of this feast, we must understand the main course.

The Glyptodont was a marvel of evolutionary engineering. Belonging to the superorder Xenarthra—which includes today's sloths, anteaters, and armadillos—the glyptodonts were the tanks of the Pleistocene.

Neosclerocalyptus was not the largest of its kind (that title belongs to the chaotic-looking Doedicurus), but it was still a formidable beast. Imagine an animal the size of a Volkswagen Beetle, weighing roughly 300 to 400 kilograms (660 to 880 lbs). The Living FortressIts most defining feature was its carapace. Unlike the banded, flexible armor of modern armadillos, the glyptodont's shell was a rigid, solid dome made of thousands of interlocking bony plates called osteoderms. Each plate was hexagonal, fitting together like a mosaic tiled by a master craftsman. This shell protected the animal from the terrifying predators of the time, such as the Smilodon (saber-toothed cat) and the Arctotherium (the giant short-faced bear).

But the armor didn't stop at the shell. The top of the head was covered in a bony "helmet," and the tail was encased in rings of bone, ending in a tube that could be used as a defensive weapon.

The MeatFor a human hunter, a glyptodont presented a unique problem. It was slow, cumbersome, and nearly blind, making it easy to approach. However, it was virtually impenetrable. You couldn't spear it through the shell.

This brings us back to the cut marks found by Dr. Del Papa's team. The location of the cuts suggests a sophisticated knowledge of the animal's anatomy. The hunters didn't try to smash the shell. Instead, they targeted the underbelly or the areas where the armor articulation was weakest—around the tail and the pelvis.

The cut marks on the caudal vertebrae (the tail bones) are particularly telling. The tail of a glyptodont is essentially a massive cylinder of muscle used to swing its heavy defensive tip. By slicing into the base of the tail, these early humans were harvesting a massive amount of high-quality red meat—steaks the size of logs.

Part IV: The Scene of the Feast

Let us reconstruct the event based on the forensic evidence.

It is the height of the Last Glacial Maximum. The Pampas region is not the humid, green fertile plain of today. It is cooler, drier—a vast, dusty steppe covered in hardy grasses and scrub. The Reconquista River is a lifeline in this semi-arid landscape, drawing animals from miles around.

A Neosclerocalyptus approaches the muddy bank to drink. Perhaps it is old, or sick, or perhaps it becomes stuck in the thick, suctioning mud of the riverbank—a common death trap for heavy megafauna.

A scouting party of humans spots the beast.

We do not know if they killed it or found it freshly dead. If they killed it, they likely didn't use projectile points (which are noticeably absent from this site). They may have used heavy rocks to stun it or simply harassed it until it collapsed from exhaustion.

Once the animal is down, the work begins. This is not a task for one person. It is a communal effort.

Using simple stone tools—flakes struck from quartzite or basalt—they begin the butchery. They cannot cut through the dome, so they flip the heavy carcass or work from the side. They slice through the thick skin around the tail base. The stone blades dull quickly against the tough hide and bone, so they constantly sharpen them or discard them for new flakes.

The atmosphere is one of focused intensity. This animal represents survival. Its meat will feed the group for days; its shell might serve as a temporary shelter or a windbreak; its bones could be used as fuel in a landscape where trees are scarce.

The cut marks found on the pelvis indicate they separated the hind legs, removing the massive hamstrings and quadriceps. The precision of the cuts shows they were not hacking wildly; they were following the muscle seams. This was a skilled dissection.

Part V: The Pre-Clovis Revolution

To appreciate why this discovery is so controversial, one must look at the history of American archaeology.

For most of the 20th century, the "Clovis First" model was the iron law. It stated that the Clovis people, characterized by their beautiful fluted points found in Clovis, New Mexico, were the first inhabitants, arriving roughly 13,000 years ago.

Evidence that challenged this was often dismissed, ignored, or explained away as contamination.

- Monte Verde, Chile: In the 1970s and 80s, Tom Dillehay excavated a site that dated to 14,500 years ago. It took decades for the scientific community to accept it.

- White Sands, New Mexico: Recently, fossilized human footprints were dated to roughly 23,000 years ago. This was a massive blow to the Clovis model, but some critics still argued about the dating methodology of the aquatic seeds used for the radiocarbon tests.

- Pedra Furada, Brazil: Sites here have yielded dates of 30,000+ years, but the "tools" found were often argued to be "geofacts" (rocks broken naturally by falling from cliffs).

The Reconquista River glyptodont cuts through the noise. We have direct interaction between humans and megafauna. We have unambiguous cut marks analyzed with modern technology. We have reliable carbon dating of the bone collagen itself.

It solidifies the "Pre-Clovis" reality. The Americas were not an empty continent waiting for the ice to melt. They were a populated landscape, filled with diverse cultures who had adapted to everything from the high Andes to the Amazonian jungles and the dry Pampas, thousands of years before the invention of the Clovis point.

Part VI: The Mystery of the Missing Tools

One question remains: Where are the tools?

In the excavation of the Neosclerocalyptus, no stone tools were found directly alongside the bones. This might seem like a weakness in the theory, but it is actually quite common in "kill sites" or "butchery sites."

Hunters value their tools. High-quality stone is heavy and hard to source. After butchering an animal, you don't leave your knife behind unless it is broken or lost. You sharpen it, pack it, and move on.

The absence of tools forces us to focus on the marks they left behind. The "signature" of the tool is written on the bone. The V-shape profile is the ghost of the knife.

Furthermore, the technology used 21,000 years ago in South America was likely "expedient." They didn't necessarily craft beautiful, symmetrical spear points that took hours to make. They likely used "flakes"—sharp shards of rock struck off a core in seconds. These tools are incredibly sharp, sharper than surgical steel, but they look like rubbish to the untrained eye. It is possible that the tools were there, but looked so much like the surrounding gravel that they were missed in earlier surveys, or simply that the humans took their favored blades with them.

Part VII: Living with Monsters

The "Glyptodont Feast" also changes how we view the extinction of the megafauna.

There has been a long-standing debate: Did humans kill the megafauna (Overkill Hypothesis), or did Climate Change kill them?

The date of 21,000 years ago suggests a much longer period of coexistence. If humans arrived 13,000 years ago and the megafauna vanished 12,000 years ago, it looks like a blitzkrieg slaughter. But if humans were there 21,000 years ago, they lived alongside these giant beasts for nearly 10,000 years.

This suggests a sustainable equilibrium. Humans were likely not the sole cause of extinction. They were one pressure among many. The glyptodonts survived human predation for millennia. It was likely the combination of rapid climate warming at the end of the Ice Age plus human hunting that finally drove these giants into oblivion.

Conclusion: The Deep History of the Americas

The discovery at the Reconquista River is more than just old bones. It is a testament to human resilience. It tells us that during the deepest freeze of the Ice Age, when the world was hostile and hard, humans had already mastered the landscape of South America.

They were not just surviving; they were capable of taking down (or processing) the armored tanks of the ancient world. They had knowledge of anatomy, social cooperation, and the technology to turn a fortress of bone into a feast of survival.

As we look at the muddy banks of the river today, passing through the urban sprawl of Buenos Aires, it is haunting to imagine that spot 21,000 years ago. The roar of traffic replaces the wind of the steppe. But the bones remain, silent witnesses to a dinner that happened deeper in time than we ever dared to dream. The history of the Americas is longer, richer, and more complex than we ever knew—and the feast has only just begun.

Reference:

- https://www.livescience.com/archaeology/humans-reached-argentina-by-20000-years-ago-and-they-may-have-survived-by-eating-giant-armadillos-study-suggests

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2024/07/240717162440.htm

- https://www.anthropology.net/p/ancient-butchery-marks-reveal-early

- https://popular-archaeology.com/article/evidence-for-butchery-of-giant-armadillo-like-mammals-in-argentina-21000-years-ago/

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/was-this-giant-armadillo-like-animal-butchered-by-humans-in-argentina-21000-years-ago-180984731/

- https://archaeologymag.com/2024/07/armadillo-fossil-reveals-early-human-presence-in-argentina/

- https://www.sci.news/archaeology/stone-tool-marks-glyptodont-bones-argentina-13106.html

- https://www.popsci.com/science/humans-butchering-armadillos/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/history/comments/1edsn4f/archaeologists_find_stone_tool_marks_on/

- https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0304956

- https://www.reddit.com/r/Naturewasmetal/comments/jdxtc7/11000_years_ago_these_giant_armadillos_called/