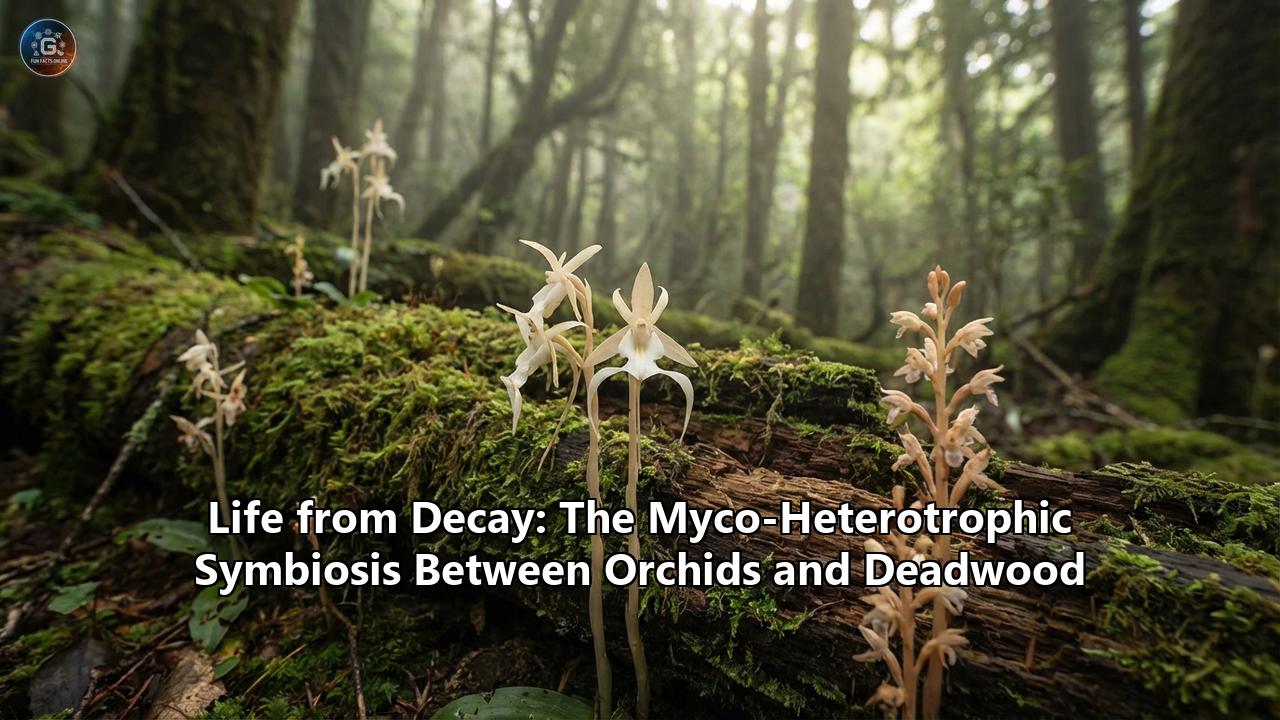

In the deepest recesses of the old-growth forest, where the canopy is so thick that sunlight strikes the floor only in fleeting, dappled coins, a mystery unfolds in the gloom. Here, amongst the damp leaf litter and the rotting carcasses of fallen giants, grows a plant that defies the most basic definition of its kingdom. It has no green leaves. It seeks no sun. It is a pale, spectral thing—sometimes translucent white, sometimes a bruised purple or earthy brown—rising from the decay like a phantom.

For centuries, these organisms were misunderstood, misclassified, and dismissed as mere "saprophytes"—plants that feed on the dead. But science has since peeled back the soil to reveal a reality far more complex and calculating. These are the myco-heterotrophic orchids, the hackers of the forest wide web. They do not eat the dead directly; they eat the eaters of the dead. And their survival is inextricably tied to one of the most overlooked and undervalued components of the forest ecosystem: deadwood.

This is the story of a hidden symbiosis, a chemical heist, and a critical pathway of carbon that flows from the rotting heart of a log into the delicate bloom of an orchid.

Part I: The Ghost in the Machine

To understand the marvel of the deadwood orchid, one must first dismantle the primary rule of botany: photosynthesis. The vast majority of plants are autotrophs, self-feeders that use chlorophyll to convert sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide into sugars. This is the energetic foundation of life on land.

But evolution is a tinkerer, and in the shaded understory of dense forests, sunlight is a scarce currency. Over millions of years, certain orchid lineages began to cheat. They abandoned the costly machinery of photosynthesis. They shed their chlorophyll, their leaves withered into vestigial scales, and they retreated underground. These plants became "myco-heterotrophs" (fungus-feeders).

For a long time, botanists labeled them "saprophytes," believing they absorbed nutrients directly from decaying organic matter, much like a mushroom does. We now know this is physiologically impossible for plants. Plants lack the enzymatic toolkit to digest wood or leaf litter directly. Instead, they outsource the digestion. They tap into the hyphae—the thread-like underground networks—of fungi that can digest wood.

While many orchids tap into mycorrhizal networks connected to living trees (stealing sugars the fungus got from a pine or oak), a specialized subset has evolved to tap into saprotrophic fungi—the decomposers. These orchids have effectively plugged themselves into the energy stored in deadwood. They are running on the batteries of the forest's past, drawing life from the carbon stored in trees that died decades ago.

Part II: The Fungal Engine—White Rot and Brown Rot

The bridge between the dead log and the living orchid is the fungus. The specific partners in this dance are often wood-decaying specialists like Mycena, Marasmius, Psathyrella, and the formidable Armillaria (honey fungus).

These fungi possess a superpower that plants lack: the ability to manufacture oxidative enzymes like lignin peroxidase and manganese peroxidase. These biological catalysts allow the fungi to break down lignin—the tough, complex polymer that gives wood its stiffness and protects the cellulose inside.

- White rot fungi break down both lignin and cellulose, leaving the wood bleached and fibrous.

- Brown rot fungi selectively attack cellulose and hemicellulose, leaving behind the dark, cubical blocks of lignin.

As the fungi penetrate the cellular matrix of a fallen log, they metabolize the wood, converting it into simple sugars and amino acids. This nutrient-rich cocktail is transported through the fungal hyphae, which fan out into the soil or the crumbling wood matrix.

It is here, in the dark interface between soil and wood, that the orchid lies in wait.

Part III: Anatomy of a Theft

The point of contact between the orchid and the fungus is a subterranean marvel. Deadwood-dependent orchids do not have typical roots. Instead, they often possess a specialized, fleshy underground stem called a rhizome. In species like the Spotted Coralroot (Corallorhiza maculata) of North America or the Ghost Orchid (Epipogium aphyllum) of Eurasia, this rhizome is "coralloid"—branching and knobby, resembling a piece of marine coral.

This shape is not accidental. The intricate branching maximizes the surface area for fungal colonization. The orchid sends chemical signals into the soil, acting as a lure. The saprotrophic fungus, sensing a potential partner (or perhaps perceiving the orchid as just another piece of wood to colonize), grows its hyphae into the orchid’s rhizome cells.

Inside the orchid’s cells, the fungal hyphae coil into tight, complex balls called pelotons. In a typical symbiotic relationship, this would be a trading post: the fungus offering minerals, the plant offering sugars. But the deadwood orchid has no sugars to give. It is a biological dead end for the fungus.

Once the peloton is fully formed and laden with carbon derived from the rotting log, the orchid activates a digestive mechanism. It releases enzymes that dissolve the fungal cell walls, causing the peloton to collapse. The orchid then absorbs the nutrient soup—carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus—directly into its own tissues. It is a cycle of "digest and wait." The orchid allows the fungus to recolonize its cells, only to digest it again. It is a distinctive form of parasitism where the plant farms the fungus inside its own roots.

Part IV: The Carbon Dating Detective Story

For decades, the link between orchids and deadwood was largely observational. Botanists saw orchids growing near rotting logs and assumed a connection. But proving that the carbon in the orchid came specifically from the deadwood (via the fungus) rather than from living trees (via a shared mycorrhizal network) required a piece of 20th-century technology: the nuclear bomb.

In a landmark set of studies, researchers, including teams from Kobe University in Japan, utilized radiocarbon dating to trace the source of the orchids' food. Atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons in the 1950s and 60s released a "pulse" of Carbon-14 (radiocarbon) into the atmosphere. Living trees absorb this atmospheric carbon in real-time. Therefore, an orchid feeding on a fungus connected to a living tree would have a Carbon-14 signature matching the current atmosphere.

However, wood decays slowly. A log rotting on the forest floor might have grown 50 or 100 years ago, trapping carbon from a pre-bomb or early-bomb era.

When researchers tested species like Gastrodia elata and Eulophia zollingeri, they found the "bomb carbon" signature was distinct. The carbon in these orchids was "old." They were built from atoms that had been pulled from the air decades prior, stored in the wood of a tree, released by a fungus, and finally assimilated by the orchid. This provided irrefutable proof: these plants are the final destination of a saprotrophic chain, literally reincarnating the dead forest into living flowers.

Part V: Global Case Studies

The dependence on deadwood manifests in spectacular forms across the globe.

1. The Vampire of the East: Gastrodia and the Honey Fungus

In the bamboo and oak forests of East Asia, the genus Gastrodia reigns supreme. The most famous, Gastrodia elata, is a giant among myco-heterotrophs, sending up flower spikes that can reach two meters tall.

Gastrodia has a particularly dangerous partner: Armillaria mellea, the Honey Fungus. Armillaria is a pathogenic giant, capable of killing living trees and consuming dead wood with aggressive efficiency. For most plants, an infection by Armillaria is a death sentence. The fungus invades the roots and rots the plant from the bottom up. Gastrodia turns the tables. It has evolved to require attack. Its tubers remain dormant in the soil until they are invaded by Armillaria rhizomorphs (thick, shoestring-like fungal cords). Instead of succumbing to the rot, the orchid tuber contains the infection and begins to digest the invader. The energy Armillaria strips from the surrounding wood is funneled into the orchid, fueling its rapid, asparagus-like growth in the spring. Without the "wood-eating killer," the orchid cannot bloom.2. The Coral Roots of the Americas

In the coniferous forests of North America, the Coralroots (Corallorhiza spp.) paint the forest floor. Species like the Spotted Coralroot (C. maculata) and the Striated Coralroot (C. striata) are often found in close association with woody debris.

While some Corallorhiza species associate with fungi linked to living trees (ectomycorrhizal fungi like Russula), others are plastic in their needs. Recent research suggests a spectrum: some coralroots may switch between carbon sources or rely more heavily on the saprotrophic capabilities of their partners depending on the abundance of deadwood. This flexibility allows them to colonize disturbed areas where trees have fallen due to windthrow or disease.

3. The Ghost Orchid of Europe

The Ghost Orchid (Epipogium aphyllum) is the "holy grail" for European botanists. It is notoriously ephemeral, sometimes not appearing above ground for decades. When it does, it emerges as a pale, translucent stem with hanging, orchidaceous flowers.

While Epipogium aphyllum is often linked to ectomycorrhizal fungi (connecting it to living pine or beech trees), its tropical cousin, Epipogium roseum, and related species have been shown to associate with Coprinoid fungi (ink caps) and Psathyrellaceae—classic litter and wood decomposers. The boundary here is porous; the "Ghost" seems capable of exploiting a wide range of fungal intermediaries, but its habitat preference for deep leaf litter and rotting substrate hints at a strong reliance on the decay web.

Part VI: The Nursery Log

The relationship with deadwood is most critical at the very beginning of the orchid's life. Orchid seeds are microscopic, often described as "dust seeds." They lack endosperm—the food reserve that typical seeds (like beans or corn) use to germinate. A fallen orchid seed is helpless; it has no energy to grow a root or a leaf.

To survive, the seed must be infected by a compatible fungus almost immediately. Recent research has shown that for many forest orchids, even those that eventually turn green and photosynthesize, deadwood is the nursery.

Studies have observed that orchid germination rates are significantly higher in the immediate vicinity of decaying logs. The logs act as a moisture sponge, maintaining the high humidity required for the fungal partners to thrive. The fungi, feasting on the log, form a dense mycelial network in the surrounding soil. When the orchid dust settles here, it lands on a "platter" of food. The fungus penetrates the seed, providing the carbon necessary for the formation of the protocorm—the blob-like precursor to the seedling.

Without the rotting log to support the fungus, the seed would remain sterile dust. Thus, the fallen tree is not just debris; it is the cradle of the next generation of orchids.

Part VII: Conservation—Deadwood is Not Dead

The revelation of this complex web has profound implications for forest management and conservation. For decades, "clean" forestry was the norm. Dead trees were removed to reduce fire risk, prevent the spread of pests, or simply to "tidy up" the woods.

We now understand that this practice severs the artery of life for myco-heterotrophic orchids. By removing coarse woody debris, we starve the saprotrophic fungi. When the fungi starve, the orchids that depend on them—either for their entire lives or just for germination—vanish.

The conservation of species like the Crested Coralroot (Hexalectris spicata) or the enigmatic Gastrodia requires more than just protecting the plant itself; it requires protecting the process of decay. This means:

- Leaving the Logs: Forestry protocols now increasingly encourage leaving "coarse woody debris" on the forest floor.

- Preserving the Canopy: These fungi require moist, humid conditions. Clear-cutting dries out the soil, killing the fungal networks even if the wood remains.

- Understanding the Micro-habitat: It's not just about any wood. Different orchids may require wood at different stages of decay (from hard logs to soft, spongy mulch) and even specific tree species (oak vs. pine).

Conclusion: The Beautiful Parasite

The myco-heterotrophic orchid challenges our romanticized view of nature. It is not a producer, but a thief. It does not stand alone, but relies on a tripartite entanglement of tree, fungus, and flower. Yet, there is a profound beauty in its dependency.

These orchids are the ultimate manifestation of the forest's efficiency. They prove that nothing is wasted. The carbon atom that built a pine needle in 1950, which fell to the forest floor in 1980, and was eaten by a fungus in 2010, may today bloom as a waxen, white flower in the deep shade.

In the life of the deadwood orchid, we see the forest not as a collection of trees, but as a singular, breathing organism, where death is simply a transfer of energy, and decay is the soil from which the strangest and most beautiful life arises.

Reference:

- https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/1100983

- https://www.spacedaily.com/reports/Some_non_photosynthetic_orchids_consist_of_dead_wood_999.html

- https://www.fnai.org/PDFs/FieldGuides/Hexalectris_spicata.pdf

- https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/hexalectris_spicata.shtml

- https://gobotany.nativeplanttrust.org/species/corallorhiza/maculata/

- https://plantae.org/some-mycoheterotrophic-orchids-depend-on-carbon-from-deadwood-novel-evidence-from-a-radiocarbon-approach-new-phytol/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wullschlaegelia

- https://fsus.ncbg.unc.edu/show-taxon-detail.php?taxonid=768

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8894228/

- https://www.earth.com/news/fungi-in-deadwood-help-orchids-grow-in-the-dark/

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/10/251008030934.htm

- https://scitechdaily.com/the-surprising-way-deadwood-brings-orchids-to-life/

- https://www.swcoloradowildflowers.com/White%20Enlarged%20Photo%20Pages/corallorhiza.htm

- https://www.hardyorchidsociety.org/orchidphotos/epipogium-aphyllum/jQueryGallery1/e-aphyllum.html