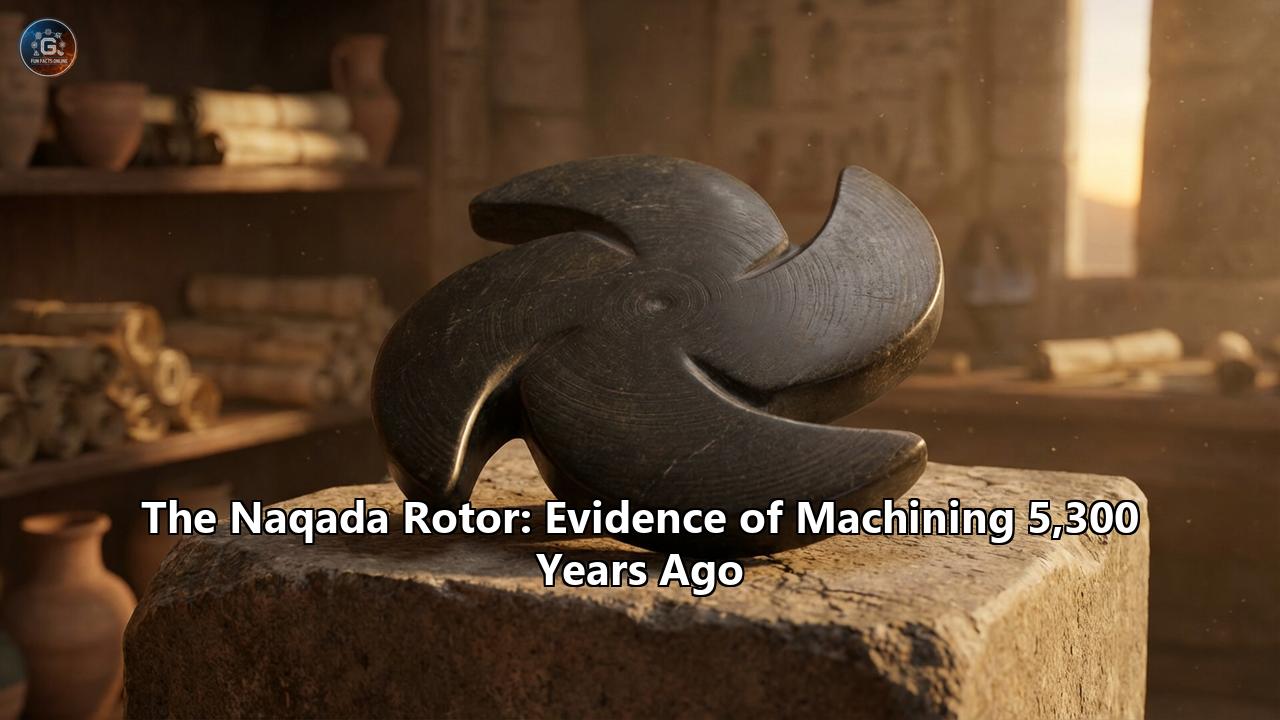

The blistering heat of the Egyptian desert hides many secrets, but few are as confounding as the artifact buried within the Mastaba of Sabu. Known to archaeologists as the "Schist Disk of Sabu" and to a growing community of engineers and alternative historians as the "Naqada Rotor," this single object has become the focal point of a fierce debate concerning the technological capabilities of the ancients.

Dated to approximately 3100–3000 BC—often rounded in alternative circles to 5,300 years ago to emphasize its connection to the Naqada period—this artifact defies the conventional timeline of history. It is a piece of precision engineering carved from delicate, brittle rock, appearing centuries before the wheel was supposedly invented in Egypt.

The Discovery: A Tomb of Shadows

The story begins in January 1936, at the edge of the plateau in North Saqqara. Renowned British Egyptologist Walter Bryan Emery was excavating Tomb 3111, the final resting place of Prince Sabu, a son of the Pharaoh Anedjib (Fifth King of the First Dynasty). The tomb was a complex structure of seven chambers, rich with grave goods—stone vessels, flint knives, and ivory boxes—meant to accompany the noble into the afterlife.

But in the center of the burial chamber, smashed into fragments, lay an object that did not fit.

Once reassembled by the Cairo Museum, the object revealed itself to be a bowl—or so it was labeled. It is a circular disk, approximately 61 centimeters (24 inches) in diameter and 10 centimeters (4 inches) high at the center. It features a central hub with a hole, connected to a rim by three curving, shovel-like lobes that fold inward toward the center.

It looks like a steering wheel. It looks like a propeller. It looks like a part from a modern centrifugal pump.

It does not look like a vase.

The Material Paradox

The first anomaly of the Naqada Rotor is what it is made of. The museum label identifies it as "schist," but geologists more accurately classify it as metasiltstone. This is a sedimentary rock that has undergone low-grade metamorphism. It is incredibly distinct for two reasons:

- Hardness: It is relatively hard, certainly harder than the copper tools available to the Egyptians of the First Dynasty.

- Brittleness: It is notoriously fragile. It has a tendency to flake and fracture along its layers.

To carve a simple bowl from metasiltstone is a feat of craftsmanship. To carve a complex, three-dimensional, geometrically symmetrical shape with thin, curving "blades" from a single block of this material is, according to modern stonemasons, bordering on the impossible without high-speed rotary tools. One slip of a chisel, one uneven strike, and the rock would shatter.

Yet, the disk shows no signs of being pieced together (other than the breakage from the tomb collapse). It was carved from one solid piece of stone.

The Argument for Machining

Why do engineers call it the "Naqada Rotor"? Because its form dictates function, and its form suggests rotation.

1. Aerodynamic SymmetryThe three lobes of the disk are spaced 120 degrees apart with remarkable symmetry. They curve gently, not in the manner of decorative art, which usually favors flat surfaces or relief carvings, but in the manner of a functional surface meant to interact with a fluid or gas. If you were to spin the disk, the lobes would act to scoop or propel air and water. This "impeller" shape is complex to design even on paper, let alone carve by hand.

2. The Central HubThe disk features a perfectly circular central hub with a hole, resembling a socket for a shaft. This suggests the object was meant to be mounted and spun. In a static object, like a fruit bowl or incense burner, a central tube is unnecessary and complicates the carving process significantly. In a machine part, it is essential.

3. Thinness and PrecisionThe "blades" of the disk are incredibly thin, tapering to an edge. In modern machining, creating thin fins on a rotor is done with high-speed CNC milling to prevent the vibration from cracking the material. The idea that a craftsman using a copper chisel and a stone hammer could gently chip away this material to create such thin, uniform, curved planes without snapping them is difficult for modern fabricators to accept.

4. BalanceAlthough we cannot spin the original artifact, digital scans and 3D printed replicas have shown that the object is surprisingly well-balanced. When spun, it stabilizes. A handcrafted decorative bowl does not require dynamic balance; a high-speed rotor does.

The "Lost Technology" Hypothesis

The existence of the Naqada Rotor fuels the theory that the Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods of Egypt were the inheritors of a "lost technology." Proponents of this view, such as researchers like Ben van Kerkwyk and Christopher Dunn, argue that the conventional timeline is missing a chapter.

They point out that the stone vessels from the Naqada period (4000–3100 BC) are actually superior in quality to those made in later dynasties. Thousands of diorite, granite, and porphyry vases from this era display hollowed-out interiors and thin walls that seem to require lathe technology. The Naqada Rotor, in this view, is not a ritual object but a remnant—a surviving piece of machinery from a civilization that understood mechanics far better than we give them credit for.

Some theories go as far as to suggest it was part of a generator, a water pump, or a device for refining chemicals. A popular experiment by an amateur researcher claimed that when spun and subjected to water, the disk created a specific vortex, suggesting it could be part of a hyper-efficient ancient pump.

The Mainstream Explanation: Ritual and Symbolism

Mainstream Egyptologists and archaeologists dismiss the "machine" hypothesis as anachronistic—projecting modern industrial forms onto ancient art. Their arguments are equally grounded in the context of the culture:

1. The "Unknown" FunctionArchaeologists admit they do not know exactly what the disk is. It is officially classified as a "tri-lobed bowl" or vessel. The consensus leans toward it being an elaborate incense burner or a stand for a torch/lamp. The "blades" would serve to deflect air or hold a structure in place.

2. The Lotus MotifThe shape, while mechanical to our eyes, may be an abstraction of the lotus flower, a symbol of rebirth deeply important to Egyptian religion. The three lobes could represent folded petals. In Egyptian art, functionality often took a backseat to symbolism.

3. SkeuomorphismIt is possible that the schist disk is a stone copy of an object originally made of a different material, like formed metal (copper) or even leather and wood. Egyptians were famous for making stone copies of everyday objects (like rope, baskets, and houses) for tombs to make them "eternal." If the original object was a copper oil lamp holder, the stone version would be a non-functional copy meant to last forever in the grave.

4. Absence of WearThe artifact, while broken, does not show the rotational wear patterns one would expect from a machine part used in a grinder or pump. The surface polish is consistent with the high-quality abrasion techniques (using sand and emery) known to be used by Egyptians.

A Mystery That Spins On

Whether you see a 5,300-year-old hyper-advanced rotor or a masterfully carved incense burner depends largely on the lens through which you view history.

To the engineer, the Naqada Rotor is a "smoking gun"—proof that the ancients possessed tools and knowledge that exceeded simple chisels and stones. It represents a capability to manipulate hard matter that was lost, only to be rediscovered during the Industrial Revolution.

To the historian, it is the Schist Disk of Sabu, a testament to the unparalleled patience and skill of Egyptian craftsmen who, with simple tools and infinite time, could force stone into shapes that defied the nature of the rock itself.

The artifact sits today in the Cairo Museum, largely ignored by passing tour groups rushing to see King Tut's gold. But for those who stop to look, it remains a silent, stone riddle—a rotor waiting for the machine that can spin it, or a flower waiting for the god who can smell it.

Reference:

- https://www.ancientpages.com/2013/06/30/schist-disk-mysterious-piece-sophisticated-technology-rewrite-history-scientists-not-sure-dealing/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RnAWHJk4Cak

- https://www.reddit.com/r/HighStrangeness/comments/q8rbgm/actual_lost_ancient_egyptian_technology_the_disc/

- https://www.milleetunetasses.com/blog/the-pyramids-of-the-cold/chapter-49-the-sabu-disk-is-a-solvay-disc-for-natron-chemical-manufacturing.html

- https://adam-hennessy.medium.com/the-schist-disk-2f0e687f1bcb

- https://www.ancientpages.com/2023/05/26/ai-ancient-mesopotamian-literature/

- https://www.messagetoeagle.com/forseti-norse-god-of-justice-and-lawmaker-who-lived-in-a-shining-house/