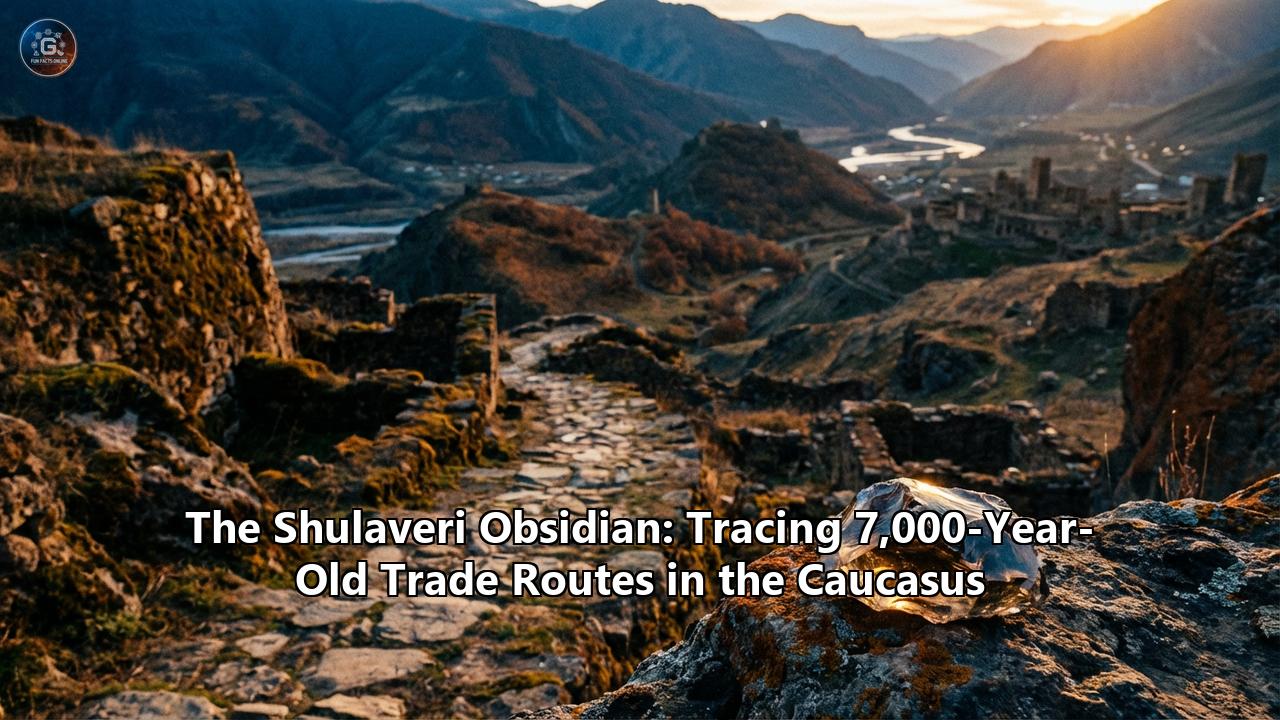

The early morning sun breaks over the Lesser Caucasus, illuminating a landscape that has served as a crossroads for human civilization for millennia. Here, in the fertile valleys of the Kura and Araxes rivers, lies the silent testimony of a people who vanished long ago but left behind a legacy etched in glass. They were the Shulaveri-Shomu, a Neolithic culture that flourished between 6000 and 4000 BCE. While they were pioneers of viticulture and circular architecture, their most cutting-edge contribution to the ancient world was not built of mudbrick, but knapped from the earth’s volcanic veins: obsidian.

For archaeologists and historians, the study of the Shulaveri-Shomu is a detective story played out on a geological scale. By chemically tracing the unique fingerprints of obsidian artifacts found in ancient settlements, we are now beginning to reconstruct a vast, 7,000-year-old web of commerce and contact that predates the Silk Road by thousands of years. This is the story of the "black gold" of the Stone Age and the trade routes that knit together the prehistoric Caucasus.

The Black Gold of the Neolithic

To understand the economic engine of the Shulaveri-Shomu, one must first understand the material itself. Obsidian is a naturally occurring volcanic glass, formed when felsic lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. The result is a material that is hard, brittle, and amorphous, capable of fracturing to produce edges sharper than the finest modern surgical steel.

For a Neolithic society lacking metal tools, obsidian was not just a luxury; it was the pinnacle of technology. It was the primary material for sickle blades used to harvest early wheat and barley; it was the scraper for processing hides; and it was the knife for daily survival.

The South Caucasus is geologically blessed with some of the world's richest obsidian sources. The volcanic highlands of modern-day Georgia and Armenia are dotted with flows that were accessible to prehistoric miners. Key sources included the Chikiani volcano in southern Georgia, and the Gegham, Gutansar, and Arteni volcanoes in Armenia. Each of these flows possesses a unique chemical signature—a specific ratio of trace elements like barium, zirconium, and rubidium—that acts as a geological barcode.

Using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and other geochemical analyses, modern researchers can scan a flake of obsidian found in a farmer's hearth at a site like Shulaveris Gora and pinpoint the exact mountainside it came from hundreds of kilometers away.

The Masters of the Blade

The Shulaveri-Shomu were not merely consumers of this material; they were industrial innovators. The hallmark of their lithic technology was the "long prismatic blade." Unlike the crude flakes of earlier epochs, these blades were standardized, mass-produced tools.

Using a technique known as pressure flaking, skilled craftsmen would prepare a "core" of raw obsidian and, using a chest crutch or a lever likely tipped with copper or antler, apply immense, controlled pressure to push off long, parallel-sided blades. This method was efficient, maximizing the amount of cutting edge that could be produced from a single block of raw stone.

At sites like Aratashen and Aknashen in the Ararat Plain, archaeologists have uncovered workshops littered with thousands of obsidian shards, cores, and finished blades. The sheer volume of debris suggests that these were not just household activities but specialized production centers. These blades were the "export grade" products of the Neolithic—lightweight, high-value, and easily transported.

Mapping the Ghost Roads

The distribution of these obsidian tools reveals the ghost roads of the Neolithic Caucasus. By mapping the distance between the sources and the settlements, a picture of complex logistics emerges.

The Northern Corridor (The Kura Valley):In the Kvemo Kartli region of Georgia, sites like Shulaveris Gora and Gadachrili Gora relied heavily on obsidian from the Chikiani source, located in the Javakheti highlands. To get this material, traders or specialized procurement parties would have had to navigate the treacherous ascent from the river valley (approx. 500m elevation) to the high volcanic plateaus (over 2,000m elevation). The presence of Chikiani obsidian in lowland farming villages implies a vertical trade network that connected the disparate ecological zones of the Caucasus—linking the high-altitude herders or miners with the lowland agriculturists.

The Southern Nexus (The Ararat Plain):In the south, settlements utilized a diverse portfolio of sources. At Aratashen, nearly all obsidian came from local Armenian sources like Arteni and Gutansar. However, as the culture matured, the network expanded. We see materials moving across the landscape in patterns that suggest more than just direct travel.

The Long-Distance Link:Perhaps the most startling discovery is the reach of these networks. Shulaveri-Shomu style blades and obsidian from Caucasian sources have been identified as far away as the site of Domuztepe in southeastern Turkey—a linear distance of over 670 kilometers, but a journey of nearly 800 kilometers on foot. This finding challenges the old view of Neolithic farmers as sedentary and isolated. It suggests that the Caucasus was not a cul-de-sac, but a bridge connecting the Near Eastern heartlands of Mesopotamia with the Eurasian steppes.

Mechanisms of Exchange: Down-the-Line or Direct Trade?

How did a razor-sharp stone travel 800 kilometers without a wheel or a pack animal? Archaeologists debate two main theories:

- Direct Procurement: In this model, individuals from the settlements traveled directly to the sources. This is likely for sites within a day or two's walk of a volcano. The physical difficulty of accessing high-altitude sources like Chikiani, which is snow-bound for months of the year, suggests that such expeditions would have been seasonal and highly organized events, perhaps embedded in summer transhumance (the movement of livestock to high pastures).

- Down-the-Line Exchange: For longer distances, obsidian likely changed hands many times. Village A traded with Village B, who traded with Village C. In this "bucket brigade" of commerce, the value of the material likely increased the further it traveled from the source. By the time a Caucasian blade reached the Halaf culture sites in Mesopotamia, it may have been regarded as an exotic, prestigious item, imbued with the mythos of distant, fiery mountains.

Social Lubricant of the Stone Age

The trade was not purely economic; it was social. In the Neolithic, exchanging gifts was a way to forge alliances, secure marriage partners, and maintain peace between potentially rival groups. A core of high-quality obsidian was a princely gift.

The presence of "exotic" obsidian—stone from a distant source when a local one was available—hints at these social networks. Why use stone from 200km away when there is a source 50km away? The answer lies in the relationship. Using stone from a distant ally signaled a connection to that group. It was a tangible representation of a social bond, a "friendship bracelet" made of volcanic glass.

Furthermore, the technology itself traveled. The spread of pressure-flaking techniques alongside the raw material suggests the movement of ideas and experts, not just stones. It implies a shared "community of practice" that spanned the entire region, unifying distinct tribal groups under a common technological umbrella.

The Legacy of the Glass Routes

The obsidian trade routes of the Shulaveri-Shomu laid the groundwork for the future of the Caucasus. The paths worn by Neolithic obsidian traders eventually became the tracks for the Kura-Araxes culture that followed, and later, the metal trade routes of the Bronze Age. When the Silk Road eventually wove its way through these valleys millennia later, it was following the topographical logic first exploited by these early stone-knappers.

Today, as we analyze these glassy artifacts in sterile laboratories, we are connecting with a vibrant, mobile, and sophisticated ancient society. The Shulaveri obsidian is more than just debris; it is a map of human ambition, proving that even 7,000 years ago, no community stood truly alone. The Caucasus was a beating heart of connection, pumping its lifeblood of black glass across the arteries of the ancient world.

Reference:

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Obsidian-procurement-in-the-northern-Near-East-and-the-southern-Caucasus_fig5_289099690

- https://caucasus.fandom.com/wiki/Shulaveri-Shomu_culture

- https://tamarnajarian.wordpress.com/2012/07/03/the-shulaveri-shomu-culture/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shulaveri%E2%80%93Shomu_culture

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OeS3QZuQ9Ds

- https://www.archatlas.org/journal/asherratt/obsidianroutes/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285778751_A_neolithic_obsidian_industry_in_the_Southern_Caucasus_Region_Origins_technology_and_traceology

- https://rscf.ru/en/news/en-57/ancient-populations-from-different-caucasus-regions-had-strong-social-connections/