The Unseen Wealth of the Abyss: How Deep-Sea Hydrocarbons and Minerals are Forged

The deep sea, a realm of crushing pressure, perpetual darkness, and frigid temperatures, was long considered a desolate wasteland. However, advances in marine geology have unveiled a dynamic and chemically complex world, a vast and largely unexplored frontier that holds the key to understanding our planet's past and potentially fueling its future. Beneath the waves, intricate geological processes have been at work for eons, slowly forging immense deposits of hydrocarbons and valuable minerals. This article delves into the fascinating and complex processes that govern the formation of these deep-sea resources, a story written in the very fabric of the ocean floor.

The Genesis of Deep-Sea Hydrocarbons: A Tale of Buried Life

Deep beneath the ocean floor lie vast reservoirs of oil and natural gas, the fossilized remains of ancient marine life. The journey from microscopic organism to valuable energy source is a long and arduous one, a multi-million-year saga of burial, transformation, and migration.

The Cradle of Life and the Rain of Organic Matter

The story begins in the sunlit upper layers of the ocean, where countless microscopic organisms, primarily phytoplankton and zooplankton, thrive. When these organisms die, their remains slowly sink, creating a continuous "marine snow" that drifts down into the deep ocean. While most of this organic matter is consumed by other organisms or decomposes in the oxygen-rich waters of the upper ocean, a tiny fraction, estimated to be around 0.1%, reaches the seafloor.

For this organic rain to become a source of hydrocarbons, it must be preserved. This is where the unique conditions of certain deep-sea environments come into play. Anoxic, or oxygen-poor, conditions are crucial for protecting the organic matter from bacterial decay. These environments can be found in stagnant basins, oxygen minimum zones, and areas of rapid sediment burial where the demand for oxygen by decomposing organisms outstrips its supply. In these settings, anaerobic bacteria, which do not require oxygen, begin the slow process of breaking down the complex organic molecules.

The Transformation into Kerogen: The Precursor to Petroleum

As layers of sediment accumulate over millions of years, the buried organic matter is subjected to increasing pressure and temperature. This process, known as diagenesis, transforms the organic material into a waxy, insoluble substance called kerogen. Kerogen is the direct precursor to oil and gas, and its composition is key to determining the type of hydrocarbons that will eventually form.

There are three main types of kerogen, each with a different potential for generating oil and gas:

- Type I Kerogen: Derived primarily from algae in lacustrine (lake) or marine environments, this type is rich in hydrogen and has a high potential to generate oil upon maturation.

- Type II Kerogen: Formed from a mixture of marine plankton and bacteria, Type II kerogen has a moderate hydrogen-to-carbon ratio and can produce both oil and gas. It is the most common type of kerogen found in marine source rocks.

- Type III Kerogen: Originating from terrestrial plant matter washed into the sea, this type is rich in oxygen and primarily generates gas when heated.

The "Oil and Gas Windows": Maturation and Generation

With continued burial, the source rock containing the kerogen descends deeper into the Earth's crust, where temperatures continue to rise. This stage, known as catagenesis, is where the magic happens. As the temperature increases, the large, complex kerogen molecules are broken down, or "cracked," into smaller, simpler hydrocarbon molecules.

This process occurs within specific temperature ranges, often referred to as the "oil window" and the "gas window." The oil window typically exists at temperatures between 65°C and 150°C (150°F to 300°F), corresponding to depths of roughly 760 to 4,880 meters (2,500 to 16,000 feet). Within this window, the kerogen generates liquid hydrocarbons, or oil.

As the source rock is buried even deeper and temperatures exceed 150°C, the cracking process becomes more intense, breaking down the oil molecules into even smaller and lighter hydrocarbon molecules, primarily methane, the main component of natural gas. This is the gas window. At extremely high temperatures, all hydrocarbons are eventually destroyed.

The Great Escape: Migration of Hydrocarbons

Once formed, the oil and gas, being lighter than the surrounding water, begin a journey upwards through the rock layers. This movement, known as migration, occurs in two stages:

- Primary Migration: This is the expulsion of hydrocarbons from the fine-grained source rock into more porous and permeable layers. The exact mechanisms are complex and still debated, but it is believed that the pressure generated by the formation of oil and gas, which occupy a larger volume than the original kerogen, plays a key role in fracturing the source rock and allowing the hydrocarbons to escape.

- Secondary Migration: Once in more permeable "carrier beds," the hydrocarbons continue their upward movement, driven by buoyancy. This migration can continue for tens of kilometers over thousands of years, until the hydrocarbons are trapped by an impermeable layer of rock, known as a cap rock or seal.

Deep-Sea Reservoirs: The Role of Submarine Landscapes

The complex topography of the deep seafloor plays a crucial role in creating the geological traps necessary for hydrocarbon accumulation. Deep marine deposits, formed by powerful underwater sediment flows, are particularly significant.

- Turbidity Currents: These are dense, fast-moving underwater avalanches of sediment and water that can travel for vast distances across the ocean floor. As they slow down, they deposit their sediment load in characteristic sequences, creating layers of sandstone with good reservoir properties.

- Debris Flows: These are even denser flows, akin to underwater landslides, that can transport a chaotic mixture of sediments. The resulting deposits can form complex reservoirs with variable porosity and permeability.

These deep-water sedimentary systems, often forming vast submarine fans at the base of continental slopes, can create the ideal combination of source rock, reservoir rock, and trap, leading to the formation of significant hydrocarbon accumulations.

An Alternative Recipe: Abiogenic Hydrocarbons

While the vast majority of hydrocarbons are formed from the remains of ancient life, there is growing evidence for another, non-biological, formation pathway. Abiogenic hydrocarbons are formed through purely chemical reactions deep within the Earth's crust and mantle.

At hydrothermal vents, geothermally heated water spewing from the seafloor creates a unique chemical environment. In a two-step process, iron compounds in the surrounding rock can strip oxygen from water, releasing hydrogen gas. This hydrogen can then react with carbon dioxide, released from magma, to form methane and other simple hydrocarbons like ethane and propane. Minerals rich in chromium can act as catalysts, speeding up this reaction. While the contribution of abiogenic hydrocarbons to commercially viable reserves is thought to be small, their existence has profound implications for understanding the deep carbon cycle and the potential for life to arise in extreme environments, both on Earth and potentially on other planets and moons in our solar system.

The Ocean's Treasure Chest: The Formation of Deep-Sea Mineral Deposits

The deep ocean floor is not only a repository of energy in the form of hydrocarbons but also a treasure chest of valuable minerals. Formed over millions of years through a variety of fascinating geological and chemical processes, these deposits represent a potential future source of critical metals for our technologically advanced society. The main types of deep-sea mineral deposits are polymetallic nodules, seafloor massive sulfides, and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts.

Polymetallic Nodules: Potatoes of the Abyss

Scattered across the vast, muddy abyssal plains of the world's oceans, at depths of 4,000 to 6,000 meters, lie trillions of potato-sized rock-like concretions known as polymetallic nodules. These nodules are rich in manganese and iron, but also contain significant quantities of valuable metals such as nickel, copper, and cobalt, as well as rare earth elements.

The formation of these nodules is one of the slowest known geological processes, with growth rates on the order of a few millimeters per million years. They form through the concentric precipitation of metal hydroxides around a central nucleus, which can be a tiny shark's tooth, a fragment of an older nodule, or even a microscopic shell.

Two primary processes contribute to their growth:

- Hydrogenous Precipitation: This involves the slow precipitation of metals directly from cold, ambient seawater onto the nodule's surface. Nodules formed primarily through this process tend to be richer in iron and cobalt.

- Diagenetic Precipitation: This process occurs at the sediment-water interface, where chemical reactions in the underlying sediments release dissolved metals into the pore waters. These metals then migrate upwards and precipitate onto the lower surface of the nodule. Diagenetic nodules are typically richer in manganese, nickel, and copper.

Most nodules exhibit a mixture of both hydrogenous and diagenetic growth layers, reflecting changes in the deep-sea environment over millions of years. For these nodules to continue growing and not be buried by sediment, there needs to be a mechanism to keep them at the surface. It is believed that the activity of deep-sea organisms, which disturb the sediment, plays a crucial role in keeping the nodules exposed.

The most significant known deposits of polymetallic nodules are found in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the Pacific Ocean, a vast area between Hawaii and Mexico.

Seafloor Massive Sulfides: Forged in Fire and Water

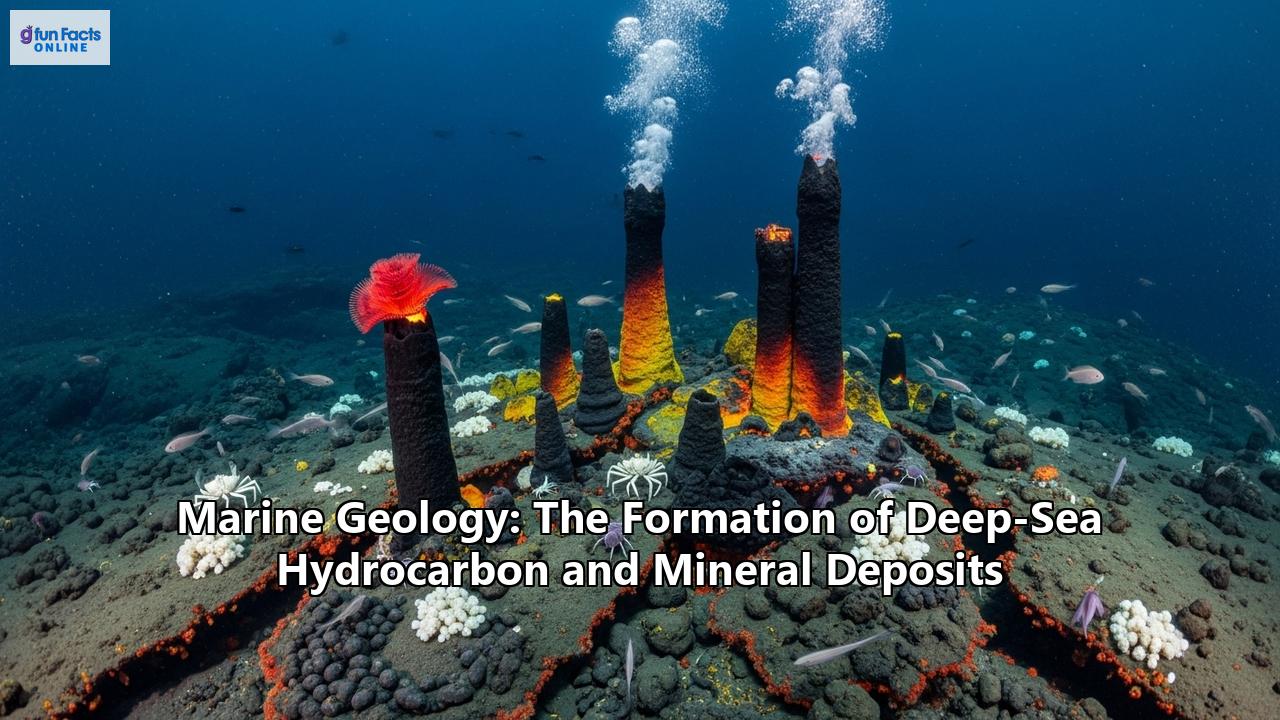

In stark contrast to the slow growth of polymetallic nodules, seafloor massive sulfides (SMS) are formed by dynamic and violent events at hydrothermal vents, often referred to as "black smokers." These vents are found along mid-ocean ridges, where tectonic plates are pulling apart and new oceanic crust is being formed.

The process begins when cold seawater seeps down through cracks and fissures in the ocean crust, sometimes for several kilometers. As the water gets closer to the underlying magma chambers, it is heated to super-hot temperatures, often exceeding 400°C (752°F). This superheated fluid becomes highly reactive, leaching metals such as copper, zinc, iron, gold, and silver from the surrounding volcanic rocks.

This hot, metal-rich, and acidic fluid then rises back towards the seafloor due to its lower density. When it erupts from the seafloor and comes into contact with the near-freezing, oxygen-rich deep-sea water, the dissolved minerals rapidly precipitate, creating a plume of black, smoke-like particles. These particles are primarily tiny mineral crystals, which settle around the vent, building up chimney-like structures and mounds of massive sulfide deposits.

These deposits often exhibit a distinct mineral zonation, with copper-rich minerals like chalcopyrite precipitating closest to the hot vent fluids, and zinc-rich minerals like sphalerite forming further away as the fluid cools and mixes with seawater.

Recent research has also highlighted the important role of microbes in the formation of these deposits. Certain bacteria can thrive in these extreme environments and their metabolic processes, particularly microbial sulfate reduction, can contribute to the initial precipitation of sulfide minerals, which then act as a nucleus for the formation of other metal sulfides.

Cobalt-Rich Ferromanganese Crusts: A Slow Coating on Undersea Mountains

Cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts are another type of deep-sea mineral deposit, found coating the flanks and summits of seamounts, ridges, and other elevated features on the ocean floor. These crusts grow very slowly, at a rate of 1 to 6 millimeters per million years, by precipitating metals directly from seawater onto hard rock surfaces.

The formation of these crusts is heavily influenced by ocean currents, which play a dual role. Firstly, they keep the rock surfaces swept clean of sediments, which would otherwise bury the crusts and halt their growth. Secondly, the currents continuously supply a fresh source of dissolved metals to the growing crusts. Seamounts themselves can act as giant stirring rods, creating eddies that trap nutrients and dissolved metals, enhancing their deposition.

These crusts are particularly rich in cobalt, but also contain significant amounts of manganese, iron, nickel, platinum, and tellurium. The thickest and most cobalt-rich crusts are typically found at water depths of 800 to 2,500 meters, often within the oxygen minimum zone. The reasons for this specific depth preference are still being investigated. The largest known deposits of cobalt-rich crusts are located in the Pacific Ocean.

The Future of Deep-Sea Resources: Exploration, Exploitation, and Environmental Concerns

The vast and valuable resources of the deep sea are increasingly attracting the attention of governments and private companies. However, the exploration and potential exploitation of these resources present significant technological and environmental challenges.

Exploration of the deep sea relies on a suite of advanced technologies, including remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) equipped with high-resolution cameras, sonar mapping systems, and sampling tools. These vehicles allow scientists and engineers to map the seafloor, identify potential deposits, and collect samples for analysis.

The technologies for mining these resources are still largely in the developmental and testing phases. For polymetallic nodules, proposed methods include collector vehicles that would vacuum or scoop the nodules from the seafloor and transport them to a surface vessel via a riser pipe system. For seafloor massive sulfides and cobalt-rich crusts, mining would likely involve cutting and grinding the deposits from the seafloor before they are pumped to the surface.

However, the potential for deep-sea mining has raised serious environmental concerns. The direct removal of mineral deposits will result in the destruction of deep-sea habitats and the organisms that live on and within them. Many of these ecosystems are home to unique and slow-growing species, and recovery from such disturbances could take thousands of years, if it occurs at all.

Furthermore, mining operations will generate sediment plumes that could smother nearby ecosystems, and the release of toxins and noise and light pollution from machinery could have widespread impacts on marine life. There are also concerns that deep-sea mining could disturb the deep ocean's role in carbon sequestration, potentially releasing stored carbon and exacerbating climate change.

Given these significant environmental risks and the many unknowns about the deep-sea environment, there is a growing call for a precautionary approach to deep-sea mining, with many scientists and environmental organizations advocating for a moratorium on mining activities until the potential impacts are fully understood and can be effectively managed.

Conclusion: A New Frontier with Great Responsibility

The deep sea is a realm of incredible geological activity, where fundamental Earth processes create vast stores of energy and mineral wealth. From the slow burial and transformation of ancient life into hydrocarbons to the fiery birth of mineral deposits at hydrothermal vents and the patient growth of metallic crusts on undersea mountains, the formation of these resources is a testament to the power and complexity of our planet.

As humanity looks to the deep ocean to meet its growing demand for energy and minerals, we stand at a critical juncture. The potential economic benefits of these resources are undeniable, but so are the profound environmental risks of their extraction. A thorough understanding of the marine geology that governs the formation of these deposits, coupled with a deep respect for the fragile and unique ecosystems of the deep sea, will be essential as we navigate this new frontier. The responsible stewardship of the unseen wealth of the abyss is a challenge and a responsibility that we must all share.

Reference:

- https://www.deepsea-mining-alliance.com/en-gb/technologies

- https://www.arcticwwf.org/threats/deep-sea-mining/

- https://www.mdpi.com/2079-7737/14/4/389

- https://www.iucn.nl/en/story/the-impact-of-deep-sea-mining-on-biodiversity-climate-and-human-cultures/

- https://oceanrep.geomar.de/id/eprint/24639/1/Seiten%20aus%202013%20SPC-1C.pdf

- https://worldoceanreview.com/en/wor-3/mineral-resources/cobalt-crusts/

- https://deep-sea-conservation.org/key-threats/

- https://www.geomar.de/en/discover/marine-resources/cobalt-rich-crusts

- https://www.theregreview.org/2024/11/23/weighing-the-environmental-impacts-of-deep-sea-mining/

- https://dsmobserver.com/2019/10/a-primer-on-cobalt-rich-crusts/

- https://geologyscience.com/geology/black-smokers/

- https://bulletin.ceramics.org/article/the-environmental-impacts-of-deep-sea-mining/

- https://www.isa.org.jm/exploration-contracts/cobalt-rich-ferromanganese-crusts/

- https://www.geomar.de/fileadmin/content/entdecken/rohstoffe_ozean/massivsulfide/factsheet_massivsulfide_en.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264382918_Cobalt-Rich_Ferromanganese_Crusts_Global_Distribution_Composition_Origin_and_Research_Activities

- https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-105507

- https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/eng7.pdf

- https://www.tsijournals.com/articles/morphology-and-geochemistry-of-the-polymetallic-nodules-from-the-central-indian-ocean-basin.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338445158_Environmental_predictors_of_deep-sea_polymetallic_nodule_occurrence_in_the_global_ocean

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361309133_Geochemistry_of_polymetallic_nodules_from_the_Clarion-Clipperton_Zone_in_the_Pacific_Ocean

- https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/geology/article/49/2/222/591717/Microbial-sulfate-reduction-plays-an-important

- https://www.rscmme.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Aldrich-et-al.-2020-Polymetallic-Nodules-1.pdf

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/earth-science/articles/10.3389/feart.2016.00068/full

- https://deepseamining.ac/article/16

- https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/geology/article-abstract/48/3/293/579958/Environmental-predictors-of-deep-sea-polymetallic

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manganese_nodule

- https://discoveryalert.com.au/news/manganese-nodules-formation-composition-2025/

- https://geoera.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/MINDeSEA_D6-2_WP6-Polymetallic-nodules-prospect-evaluation-parameters.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315859691_Composition_Formation_and_Occurrence_of_Polymetallic_Nodules

- https://www.mdpi.com/2075-163X/13/11/1431

- https://www.washington.edu/news/1998/07/18/brief-scientific-background-on-sulfide-chimneys-black-smokers/

- https://dsm.gsd.spc.int/public/files/meetings/TrainingWorkshop4/UNEP_vol1A.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IuE-4eiJvwI

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257409721_Mineralogy_and_Formation_of_Black_Smoker_Chimneys_from_Brothers_Submarine_Volcano_Kermadec_Arc

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1fB9-B-MSR0

- https://scispace.com/pdf/seafloor-massive-sulfides-from-mid-ocean-ridges-exploring-41phgy88hy.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346129439_Microbial_sulfate_reduction_plays_an_important_role_at_the_initial_stage_of_subseafloor_sulfide_mineralization

- https://www.bohrium.com/paper-details/interaction-between-microbes-minerals-and-fluids-in-deep-sea-hydrothermal-systems/813188234824646657-257

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264762832_The_Geology_of_Cobalt-rich_Ferromanganese_Crusts

- https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/70127614

- https://geoexpro.com/seabed-mineral-exploration/

- https://web.mit.edu/12.000/www/m2016/finalwebsite/solutions/oceans.html

- https://www.unido.org/publications/ot/9658118/pdf