The Neolithic revolution, often characterized by the domestication of plants and animals, the clearing of forests, and the erection of permanent settlements under the open sky, harboured a paradoxical shadow. As humanity claimed the surface of the earth for agriculture and village life, they simultaneously developed an obsession with the world beneath their feet. From the wind-swept islands of Orkney to the sun-baked limestone ridges of Malta, and deep into the chalk beds of southern England, Neolithic communities engaged in a colossal project of subterranean construction. These were not merely holes dug for shelter or storage; they were sophisticated "architectures of the negative," complex engineered spaces designed to manipulate the senses, alter human consciousness, and facilitate communication with the chthonic forces of life and death.

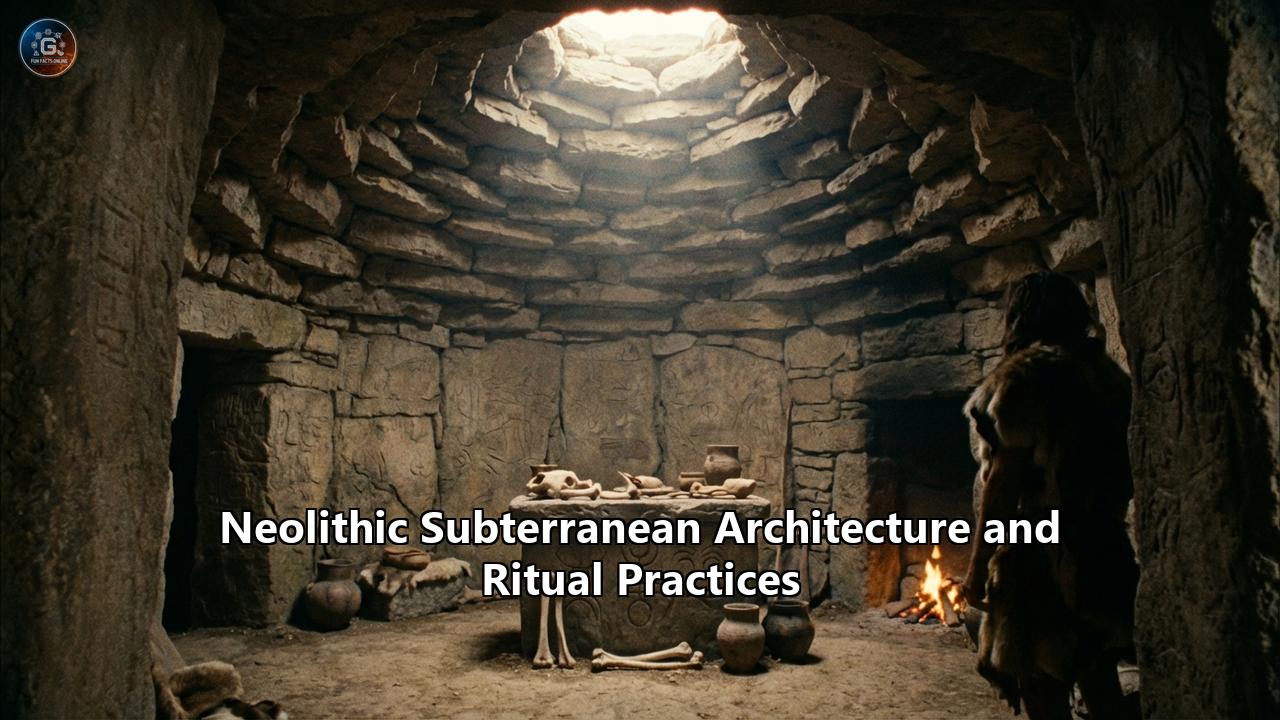

To understand the Neolithic mind, one must leave the light of the sun and descend into the dark. It is here, in the cool, echoing silence of the underground, that the true spiritual technology of the Stone Age reveals itself. This was a period when the earth was not viewed as inert matter to be exploited, but as a living, ancestral body—a womb from which life emerged and a tomb to which it must inevitably return. The subterranean structures of this era—hypogea, flint mines, chambered tombs, and sunken dwellings—were the physical interfaces of this cosmology, machines built of stone and earth designed to bridge the gap between the worlds.

The Architecture of the Negative: The Hypogeum of Ħal Saflieni

Nowhere is the Neolithic drive to build downwards more spectacularly realized than in the Hypogeum of Ħal Saflieni in Paola, Malta. Discovered accidentally in 1902 by workers cutting cisterns, this structure remains one of the most enigmatic and technically accomplished feats of prehistoric engineering. Carved entirely from living globigerina limestone using nothing but obsidian blades, flint scrapers, and antler picks, the Hypogeum is a subterranean necropolis and temple complex that spans three distinct levels, reaching a depth of over ten meters.

The structure is dated to the Saflieni phase (3300–3000 BC), though its origins may be older, and it remained in use for centuries. What makes the Hypogeum unique is not just its depth, but its architectural mimicry. The builders did not simply hollow out a cave; they sculpted the rock to imitate the built environment of the surface. The chambers feature carved trilithons, lintels, and corbelled ceilings that mirror the megalithic temples of Hagar Qim and Mnajdra standing above ground. It is a temple inverted, a "negative" image of the world of the living projected into the realm of the dead.

The descent into the Hypogeum is a journey through time and sensory deprivation. The Upper Level, the oldest part, consists of irregular hollows that likely started as a natural cave system before being expanded. But as one descends to the Middle Level, the architecture becomes precise, geometric, and overwhelmingly impressive. Here lies the "Holy of Holies," a room with a carved façade so perfectly executed it appears to be built of masonry blocks, though it is entirely hewn from the bedrock.

However, the visual splendour of the Hypogeum is secondary to its acoustic power. Recent archaeoacoustic research has revealed that the builders of Ħal Saflieni possessed a profound, perhaps intuitive, understanding of sound. The complex, particularly the chamber known as the "Oracle Room," behaves like a giant resonance box. The Oracle Room features a small oval niche cut into the wall at face height. When a deep male voice chants into this niche, the entire complex vibrates.

Scientific studies have pinpointed the resonant frequency of this chamber at approximately 110 Hz. This is not a random figure. Neuroscientific research suggests that exposure to sound frequencies in the range of 110 Hz switches off the language-processing center of the brain (the left temporal lobe) and stimulates the right prefrontal cortex, the region associated with mood, empathy, and social behaviour. In a ritual context, chanting at this frequency would have induced a trance-like state in the participants, blurring the boundaries of the self and fostering a profound sense of connection—both with the community and the ancestors whose bones filled the surrounding chambers.

Imagine the sensory experience of the Neolithic initiate: descending from the blinding Mediterranean sun into the cool, absolute darkness of the earth. The air is still and smells of damp limestone and ochre. Flickering fat lamps cast dancing shadows against the walls, which are painted with red spirals—the eternal symbol of life’s continuity. Then, the chanting begins. It does not sound like it is coming from a specific direction; the standing waves created by the architecture make the sound omnipresent, appearing to emanate from the walls, the floor, and the listener’s own chest. It is a visceral, bone-shaking experience that dissolves the barrier between the physical body and the stone womb of the earth. The Hypogeum was not merely a place to store the dead (the remains of some 7,000 individuals were found there); it was a machine for the transformation of the living.

The Womb of the Earth: Chambered Tombs and Passage Graves

While the Hypogeum is a vertical descent, the passage tombs of Atlantic Europe offer a horizontal journey into the earth, though the symbolism remains remarkably similar. From the Brugh na Bóinne in Ireland to the cairns of Orkney and the dolmens of Brittany, these monuments consist of a long, narrow passage leading to a central chamber, covered by a massive mound of earth and stone.

For decades, archaeologists debated whether these were houses for the dead or temples for the living. The consensus today is that they were both, and perhaps more importantly, they were liminal zones. The architecture of the passage tomb is explicitly anatomical. Many scholars have noted the resemblance of the plan—a long passage opening into a rounded chamber—to the female reproductive system. To enter the tomb is to return to the womb of the Great Mother.

At Newgrange in Ireland (c. 3200 BC), this symbolism is activated by the cosmos itself. The monument is oriented with such precision that at sunrise on the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, a beam of sunlight penetrates the "roof box" above the entrance. It travels down the 19-meter passage and strikes the floor of the central chamber, illuminating the triple-spiral carvings on the rear stone. For 17 minutes, the dark womb is impregnated by the light of the sun. This was not a passive observation of the seasons; it was a ritual act of cosmic regeneration. In the depth of winter, when the world seemed to be dying, the Neolithic people engineered a moment of conception to ensure the return of life.

The acoustic properties of these spaces are equally significant. At Maeshowe in Orkney, a masterpiece of Neolithic masonry constructed around 2800 BC, the central chamber is a vast, corbelled cathedral of stone. The acoustic resonance here is profound. A hum or a drumbeat can generate standing waves that are so intense they can be physically felt. In the flickering light, these sound waves can even cause dust to dance, creating a visual manifestation of the "spirits."

Recent DNA analysis of the bones found in these Irish passage tombs has added a startling layer of social complexity to our understanding. While it was long suspected that these were elite monuments, genetic testing of remains from Newgrange and its sister sites suggests an dynastic lineage, with evidence of close kin matings (incest) among the buried elite, mirroring the practices of later "god-kings" like the Egyptian Pharaohs. However, the spaces themselves were likely used by a broader community for gathering. The acoustics, the alignment, and the art were theatrical elements designed to reinforce the power of those who held the keys to the underworld. The ability to control the sun and speak with the booming voice of the ancestors would have granted the priesthood or ruling family immense authority.

The Industrial and the Sacred: The Ritual of the Mine

Not all Neolithic subterranean structures were tombs or temples. Some were industrial sites, yet even here, the distinction between the functional and the sacred blurs. The flint mines of Grimes Graves in Norfolk, England, and Spiennes in Belgium represent some of the earliest large-scale industrial engineering in history.

At Grimes Graves (c. 2600 BC), miners used antler picks to dig vertical shafts up to 13 meters deep through solid chalk to reach the "floorstone," a layer of superior quality jet-black flint. This effort was colossal. The amount of chalk removed to create a single shaft is staggering, and there are over 400 such shafts at the site.

Archaeologists have long puzzled over why these miners went to such extreme lengths. Surface flint was abundant and functional, yet they bypassed it to dig deep into the dangerous dark. The answer likely lies in the symbolic value of the deep earth. Flint was the steel of the Neolithic—the material of axes, knives, and fire. To extract it from the deepest bowels of the earth was perhaps to harvest a material that was more "charged" or "potent" than the weathered stone found on the surface.

The archaeology of Grimes Graves reveals that mining was a ritualized activity. In the silent galleries radiating from the bottom of the shafts, miners left offerings. One famous discovery in "Pit 15" included a small altar of flint lumps, upon which was placed a chalk carving of a fat, female figurine (often called the "Chalk Goddess") and a chalk phallus, flanked by piles of deer antler picks. This is not the debris of industry; it is a shrine.

The symbolism is potent: the shaft is a penetration of the earth; the chalk phallus and the pregnant goddess represent a fertility rite. The miners were not just extracting stone; they were engaging in a reciprocal exchange with the earth. They offered antlers (symbolizing the wild, renewable power of nature) and votive carvings in exchange for the "bones" of the earth (the flint).

There is also a darker aspect to these mines. Lighting was provided by bowls of burning animal fat, which would have filled the galleries with acrid smoke. The air would have been thick with chalk dust. The physical exertion of swinging a pick in a cramped, claustrophobic tunnel, combined with the flickering light and the sensory deprivation, would have induced altered states of consciousness. Mining was a hallucinatory, perilous descent into an alien world. The "Greenwell’s Pit" at Grimes Graves yielded the skeleton of a dog that had been carefully buried—possibly a guardian to watch over the miners or a sacrifice to the spirits of the chalk.

Dwellings of the Living, Dwellings of the Dead

While the "houses of the dead" (tombs) were often subterranean, in some Neolithic cultures, the "houses of the living" also hugged the earth. In the Levant and parts of China, semi-subterranean architecture was a common adaptation, offering thermal insulation against extremes of heat and cold.

In the Yangshao culture of Neolithic China (c. 5000–3000 BC), villages like Banpo (near modern Xi'an) consisted of circular and square houses sunk halfway into the ground. These were roofed with timber and thatch, but the living floor was a meter or more below the surface. Entering the home meant stepping down. While practical, this architecture also reinforced a connection to the earth. The hearth, the center of the home, was grounded in the soil.

In the Levant, specifically during the Ghassulian Chalcolithic (which overlaps with the late Neolithic traditions), we find the enigmatic underground dwellings of the Beer Sheva culture. At sites like Bir Abu Matar, entire communities lived in subterranean networks of tunnels and chambers. These were not merely basements; they were complex multi-room habitats. The reasons for this are debated—defense? Climate control?—but they align with a broader regional fascination with the underground.

It is in the Levant that we also see the starkest contrast between the house of the living and the house of the dead, yet both occupy the rock. The usage of natural and artificial caves for ossuary burials (secondary burial of bones in ceramic boxes) in this region suggests a worldview where the dead must physically return to the rock from which the water and life of the region spring. The cave of Peqi'in in Upper Galilee yielded fantastical ossuaries decorated with faces, seemingly staring out from the dark, guarding the passage between worlds.

The Phenomenology of the Underworld

Why did Neolithic people go underground? The labour required to excavate the Hypogeum or the deep shafts of Grimes Graves was immense, far exceeding the functional necessities of burial or flint extraction. The answer lies in the phenomenology of the space itself.

Underground spaces are "liminal"—they exist on the threshold. They are neither wholly of the world (the surface, the light, the domain of the living) nor wholly of the void. They are spaces of transition.

1. Sensory Deprivation and Altered States:In the deep dark, the human sensory system goes into overdrive. The lack of visual stimuli causes the brain to hallucinate, a phenomenon known as the "prisoner's cinema." The silence (or the specific acoustic resonance) alters brain waves. Neolithic shamans or priests likely understood this biology intuitively. The underground chamber was a technology for inducing visions. By isolating the initiate from the rhythms of the day and night, the chaos of the village, and the visual clutter of the landscape, the architecture forced an inward journey.

2. The Acoustic Shadow:We have touched on the 110 Hz resonance, but the general acoustic "wetness" of these stone chambers is crucial. In the open air, sound dissipates. In a stone chamber, it is contained, amplified, and sustained. A drum beat does not just happen and end; it hangs in the air, overlapping with the next beat. This creates a sonic wall, a "thick" atmosphere that envelops the participant. For a pre-industrial people, who never experienced artificial amplification, the booming voice of a priest in a passage grave would have sounded supernatural—literally the voice of a god.

3. The Thermal Constancy:The underground is timeless. While the surface world freezes in winter and scorches in summer, the deep earth maintains a constant temperature (roughly 13-15°C in temperate zones). To enter a passage grave in the depth of a freezing midwinter is to enter a warm, stable embrace. To enter in the heat of summer is to find cool relief. This thermal stability reinforces the idea of the underworld as a place of eternity, untouched by the passing seasons that ravage the surface. It is the perfect static realm for the ancestors.

The Legacy of the Deep

The Neolithic obsession with the underground eventually faded in many regions, replaced by the sky-centric religions of the Bronze Age, where focus shifted to solar alignments, stone circles, and eventually, gods that dwelt on mountain tops or in the heavens. The womb of the earth gave way to the eye of the sun.

However, the legacy of these subterranean practices remains etched in the human psyche. The myths of descent—Orpheus, Inanna, Persephone—are echoes of the rituals that once took place in the dark chambers of Malta and Ireland. The idea that wisdom, rebirth, and power reside in the dark places of the earth is a concept that was physically constructed by our Neolithic ancestors.

Today, as we stand inside the corbelled roof of Maeshowe or gaze at the ochre spirals of the Hypogeum, we are not just looking at "architecture." We are standing inside the fossilized psychology of the Stone Age. We are witnessing the moment when humanity first realized that to understand the height of the heavens, they had to plumb the depths of the earth. They built downwards to find the eternal, and in the silence of the rock, they found a way to speak to the ages.

Case Study: The Acoustics of the Oracle

To truly appreciate the sophistication of these spaces, one must look closer at the "Oracle Room" in the Hal Saflieni Hypogeum. The niche is carved at roughly the height of a person's mouth. The chamber ceiling is curved and painted with intricate red spirals that resemble the branching of trees or the flow of blood.

When a voice projects into the niche, the sound waves are not scattered. The curvature of the ceiling acts as a focusing lens, while the density of the limestone creates a high "Q-factor" (low energy loss). The room holds onto the sound. The specific dimensions of the chamber create a standing wave at 110 Hz.

Modern acoustic physics tells us that 110 Hz is in the lower range of the male baritone voice. It is also a frequency that has been found to be resonant in other Neolithic structures, such as the passage cairns of Newgrange and the chambered tombs of Brittany. This convergence is unlikely to be a coincidence. Whether through trial and error or a lost system of acoustic measurement, Neolithic builders consistently targeted this frequency range.

Why? The "biophilia" hypothesis suggests that certain sounds trigger evolutionary responses. Low frequency, resonant sounds are often associated with large animals or natural power (thunder, earthquakes). But the 110 Hz frequency also has a specific effect on the human skull. It creates a mechanical resonance in the bone structure of the head. When you chant at this pitch in a resonant space, you don't just hear the sound; your skull vibrates. The sound becomes internal. This blurring of "inner" and "outer" sensation is the classic precursor to mystical experience. The "Oracle" did not need to be a supernatural entity; the architecture itself turned the priest's voice into the voice of the god within the listener's head.

The Global Context: From Orkney to Anatolia

While Europe offers spectacular examples, the subterranean impulse was global. At Göbekli Tepe in Anatolia (modern Turkey), often called the world's first temple (c. 9500 BC, Pre-Pottery Neolithic), the structures are not strictly subterranean but are semi-subterranean, dug into the hillside and surrounded by stone walls. However, the act of burial there is significant. These massive stone circles were deliberately buried by their creators under tons of soil. The "death" of the monument involved returning it to the earth.

In the later Neolithic of the Orkney Islands, the settlement of Skara Brae offers a domestic counterpoint. The houses are sunk into middens (mounds of waste and earth), connected by covered, subterranean passages. The villagers lived inside the earth, sheltered from the Atlantic gales. Yet, right next door at the Ness of Brodgar, massive temple-like structures were built. The fluidity between the domestic underground (warmth, safety) and the ritual underground (death, transformation) in Orkney paints a picture of a society where the earth was the primary medium of existence.

Conclusion: The Technologies of the Sacred

Neolithic subterranean architecture challenges the modern view of "primitive" man. These were not people hiding in caves from the elements. They were master engineers who treated stone, light, and sound as malleable materials. They understood that the environment dictates the state of mind.

By manipulating the physics of their world—blocking out the light, amplifying the sound, stabilizing the temperature—they created controlled environments for ritual. They built the first sensory deprivation tanks and the first concert halls. They industrialized the extraction of sacred stone and mapped the movements of the sun onto the darkness of the tomb.

The subterranean world of the Neolithic was a place of work, worship, and transformation. It was the womb from which the community was born and the vessel that carried them into the afterlife. In digging down, they were not escaping the world; they were entering its heart.

Reference:

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282480957_Archaeoacoustic_Analysis_of_the_Hal_Saflieni_Hypogeum_in_Malta

- https://otsf.org/archaeoacoustics

- https://www.thearchaeologist.org/blog/investigate-structures-built-with-unique-sound-properties-possibly-for-rituals-or-communication

- https://www.scribd.com/document/716359686/Acusticadastumbas

- https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/maltas-hypogeum

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/130/

- https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/bitstream/123456789/16630/1/OA%20Archaeoacoustic%20Analysis%20of%20the%20%C4%A6al%20Saflieni%20Hypogeum%20in%20Malta.pdf

- https://mrlyule.wordpress.com/2014/05/01/maltas-hypogeum-of-hal-saflieni/

- https://www.megalithic-visions.org/2023/02/05/dolmen-chambered-megalithic-monuments/

- https://www.knowth.com/access1.htm

- https://www.prehistoricsociety.org/sites/prehistoricsociety.org/files/resources/ps-intros-neo-7-flint-mines.pdf

- https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/grimes-graves-prehistoric-flint-mine/history/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grime%27s_Graves

- https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/grimes-graves-prehistoric-flint-mine/history/ritual-mysteries2/

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/cambridge-world-prehistory/levant-in-the-pottery-neolithic-and-chalcolithic-periods/C2081DEB0D59753AA5550C6F089E211D