The Invisible Engine: Inside the Heavy Metal Heart of the Physical Internet

In the popular imagination, the internet is ethereal—a "cloud" that floats above us, wireless, weightless, and omnipresent. We access it through panes of glass, summoning information as if by magic. But the reality of our digital lives is heavy, loud, and intensely physical. It is built of steel, concrete, fiber-optic glass, and copper. It consumes rivers of water and enough electricity to power nations.

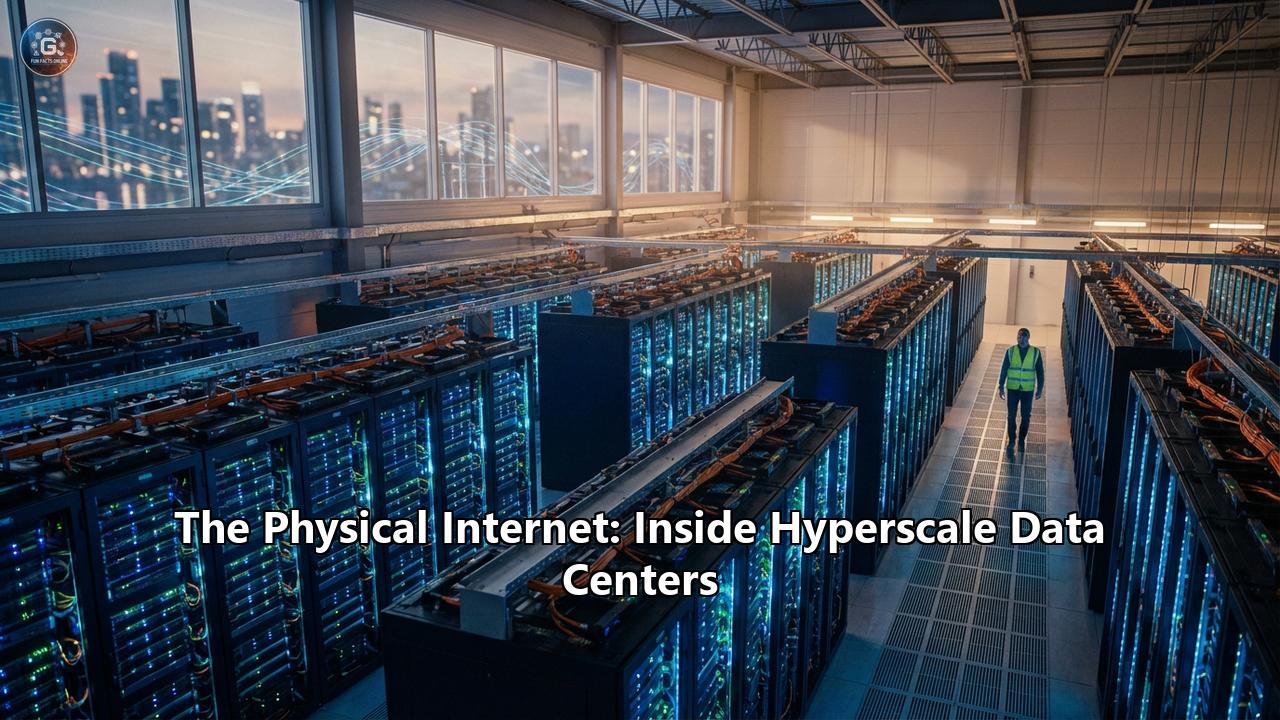

This is the story of the Hyperscale Data Center, the factory floor of the 21st century.

As we move through 2025, the physical internet is undergoing its most radical transformation since the invention of the World Wide Web. Driven by the insatiable hunger of Generative AI, these facilities are no longer just storage lockers for data; they are becoming high-performance compute engines, nuclear-powered fortresses, and the most complex engineering projects on Earth.

Chapter 1: The Anatomy of a Giant

To understand the physical internet, one must first grasp the scale. As of early 2025, there are over 1,136 hyperscale data centers in operation globally, a number that has doubled in just five years. But the raw count is misleading; the size of each facility is exploding.

A decade ago, a 10-megawatt (MW) data center was considered massive. Today, hyperscale campuses—operated by the "Big Three" (Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud) and Meta—routinely exceed 100 MW, with gigawatt-scale campuses now in the planning stages.

The Campus Layout

A modern hyperscale campus looks less like a tech headquarters and more like a high-security logistics terminal.

- The Shell: These act like warehouses for servers but are engineered to survive natural disasters. They are nondescript, windowless monoliths, often painted in neutral grays or whites to reflect heat.

- The Berm: Security often begins hundreds of feet from the building, with "hostile vehicle mitigation" barriers—landscaping designed to stop a truck bomb without looking like a fortress.

- The Power Substation: The most critical component. A hyperscale campus often has its own dedicated substation, pulling high-voltage power directly from the transmission grid, bypassing local distribution lines to ensure stability.

The Availability Zone (AZ)

Cloud architects do not trust single buildings. They build in "Availability Zones." An AZ consists of one or more discrete data centers with redundant power, networking, and connectivity. A "Region" (like AWS us-east-1 in Northern Virginia) is a cluster of these AZs. They are close enough (typically within 100 kilometers) to replicate data synchronously with low latency, but far enough apart that a flood, tornado, or nuclear event hitting one is unlikely to take out the others.

Chapter 2: The AI Metamorphosis (2024-2025)

Until 2023, data center design was evolutionary. In 2025, it is revolutionary. The culprit is Generative AI.

Traditional cloud workloads (email, web hosting, database queries) are "bursty" but manageable. AI training workloads are different. They are massive, continuous mathematical crunches that run for weeks or months at 100% utilization. This has forced a complete redesign of the facility's interior.

The Density Problem

For years, the industry standard for power density was roughly 6 to 8 kilowatts (kW) per rack.

- The Shift: In 2025, an AI training cluster utilizing NVIDIA Blackwell or similar high-end GPUs pushes rack density to 80 kW, 100 kW, or even 120 kW per rack.

- The Implication: You can no longer simply fill a room with these racks. If you placed 100kW racks in a traditional layout, they would melt the floor tiles and overwhelm the air conditioning instantly. AI data halls are now designed with lower rack counts but vastly higher power cabling and weight-bearing floors to support the heavy copper and liquid cooling systems.

Chapter 3: Thermodynamics and the Death of Air

For thirty years, we cooled computers by blowing cold air on them. Giant chillers on the roof cooled water, which ran through Computer Room Air Handlers (CRAHs) to blow cold air through a raised floor. The servers used tiny fans to scream this air over their heatsinks.

In the AI era, air is dead. Air simply cannot carry heat away fast enough from a chip running at 350°F (175°C).

The Liquid Revolution

Walk into a cutting-edge AI data hall in 2025, and it is quieter. The deafening whine of server fans is gone, replaced by the hum of pumps.

- Direct-to-Chip (D2C) Cooling: This is the current standard for hyperscalers. A cold plate sits directly on top of the GPU and CPU. Liquid coolant (often a glycol-water mix or a specialized dielectric fluid) circulates through the plate, absorbing heat right at the source. This captures about 70-80% of the heat.

- Immersion Cooling: This is the frontier. Servers are vertically dipped into tanks filled with a mineral-oil-like dielectric fluid. The liquid touches every component, boiling off at hot spots and condensing on a coil at the top of the tank (two-phase immersion). It looks like a sci-fi cauldron, but it is the most efficient way to cool high-density silicon.

Chapter 4: The Nuclear Renaissance

The single biggest constraint on the physical internet today is not land or chips; it is electricity.

A single large AI query (like generating a complex image) uses as much electricity as charging a smartphone. Training a model like GPT-5 requires gigawatt-hours of energy. The electrical grids in Northern Virginia ("Data Center Alley"), Dublin, and Singapore are buckling.

To solve this, Big Tech has gone nuclear.

The Three Mile Island & SMR Pivot

In a move that would have been unthinkable a decade ago, the tech giants are becoming utility providers.

- Microsoft & Constellation: In late 2024, Microsoft signed a deal to restart Unit 1 at Three Mile Island. The nuclear plant, site of the historic 1979 accident, is being resurrected solely to feed the Azure cloud with carbon-free baseload power.

- Google & Amazon (SMRs): Unlike traditional massive reactors, Google and Amazon are investing in Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) with companies like Kairos Power and X-energy. These are factory-built, salt-cooled reactors that can be deployed faster and more safely. By 2030, we expect to see "behind-the-meter" nuclear plants—reactors sitting right next to the data center, off the public grid entirely.

Chapter 5: The Nervous System – Connectivity

If power is the blood of the data center, fiber optics are the nerves. The physical internet is a mesh of glass strands thinner than a human hair, pulsating with laser light.

The Subsea Empire

99% of international data traffic travels underwater, not via satellite. The ocean floor is crisscrossed with cables roughly the thickness of a garden hose.

- The Shift: Historically, telecom carriers (AT&T, Verizon) owned these cables. Today, the hyperscalers own them. Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon are the dominant investors in subsea infrastructure.

- The 2025 Map: New routes are bypassing geopolitical choke points. We are seeing a massive surge in "Trans-Pacific" cables connecting the US West Coast to Japan and Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Philippines), bypassing the South China Sea where possible. The "Humboldt" cable is connecting South America directly to Australia, creating a new southern hemisphere route.

Inside the MMR (Meet-Me-Room)

The most valuable real estate in the world is not a penthouse in Manhattan; it is the Meet-Me-Room inside a carrier-neutral data center (like those owned by Equinix or Digital Realty).

This is where the networks physically touch. A yellow fiber cable from AT&T plugs into a patch panel, connecting to a blue cable from Netflix, which connects to a red cable from Google. This physical cross-connect is where the "internet" actually happens.

Chapter 6: Inside the Box – The OCP Standard

In the past, companies bought servers from Dell or HP. But hyperscalers realized that "off-the-shelf" gear was full of unnecessary plastic, video connectors, and bloated casing. They started the Open Compute Project (OCP).

The "Vanity-Free" Server

Walk down an aisle in a Meta or Google facility, and the servers look raw.

- Stripped Down: There are no logos, no bezels, no VGA ports, no unnecessary LEDs.

- Wide Racks: The standard 19-inch rack has been replaced by the OCP 21-inch rack, allowing for three motherboards to sit side-by-side, maximizing density.

- Centralized Power: Instead of every server having its own inefficient power supply unit (PSU), a "power shelf" converts AC to DC for the whole rack. This saves millions of dollars in electricity across a campus.

Custom Silicon

The servers aren't just running Intel or AMD chips anymore.

- AWS: Runs on Graviton (CPUs) and Trainium/Inferentia (AI chips).

- Google: Runs on Axion (CPUs) and TPUs (Tensor Processing Units).

- Microsoft: Runs on Maia (AI) and Cobalt (CPU).

By designing their own chips, these companies strip out logic they don't need, optimizing strictly for the workloads they run.

Chapter 7: Fortress Cloud – Security

Data center security is designed in concentric circles, modeled after onion layers.

- The Perimeter: 24/7 armed guards, crash-rated fences, and motion sensors.

- The Trap: Entry involves a "mantrap"—a small glass booth where you must badge in, be weighed (to ensure you aren't carrying unauthorized hardware in or out), and pass biometric scanners (iris or palm vein) before the second door opens.

- The Floor: Only technicians with specific tickets are allowed on the server floor.

- The Data Destruction: When a hard drive fails, it doesn't leave the building. It is shredded on-site into confetti. Google and AWS use industrial shredders that reduce storage media to dust to ensure not a single kilobyte of customer data can be recovered.

Chapter 8: The Sustainability Paradox

The data center industry is caught in a paradox. It is the largest corporate purchaser of renewable energy in the world, yet its environmental footprint is growing.

The Water Crisis

Cooling requires water—billions of gallons of it. In drought-stricken areas (like the US Southwest), data centers compete with farmers and cities for water rights.

- The Solution: "Water Positive" goals. Microsoft and Meta are investing in wetland restoration and rainwater harvesting.

- Adiabatic Cooling: Newer designs use "free cooling" (using outside air) whenever possible, only misting water to cool the air on the very hottest days.

The Carbon Ledger

While companies claim "100% Renewable," the reality is complex. They often buy Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) to offset brown power taken from the grid. The 24/7 Carbon Free Energy (CFE) movement, led by Google, aims to match energy consumption with clean generation hour-by-hour, not just annually. This is why the nuclear deals in Chapter 5 are so critical—wind and solar are not always there when the servers are crunching at 3 AM.

Chapter 9: Future Horizons

Where do we go from here?

- The Edge: Not everything needs to go to a hyperscale factory. "Edge" data centers are fridge-sized cabinets sitting at the base of cell towers, processing self-driving car data in milliseconds.

- Orbital Data Centers: Startups are testing putting servers in space to use the freezing vacuum for cooling and solar arrays for power, though latency remains a hurdle.

- Underwater: Microsoft’s Project Natick proved that sealing a data center in a nitrogen-filled pressure vessel and sinking it to the ocean floor is viable. It cools naturally, and the absence of oxygen prevents corrosion, making servers last longer.

- Lights-Out Automation: The data center of 2030 may have no humans inside. Robots (like those demoed at OCP 2025) will swap failed drives and move racks, allowing the facility to operate in the dark, with lower oxygen levels to prevent fire.

Conclusion

The physical internet is a testament to human engineering—a global machine made of millions of spinning disks, optical lasers, and silicon brains. As we lean harder into the AI era, these "cathedrals of computation" will consume more of our resources, land, and energy. Understanding them is no longer just for engineers; it is essential for understanding the infrastructure that underpins modern civilization. The cloud is not magic. It is concrete, copper, and nuclear power.

Reference:

- https://www.srgresearch.com/articles/hyperscale-data-center-count-hits-1136-average-size-increases-us-accounts-for-54-of-total-capacity

- https://www.globaldatacenterhub.com/p/what-h1-2025-just-taught-us-about

- https://stlpartners.com/articles/data-centres/data-center-liquid-cooling/

- https://www.datacenters.com/news/why-liquid-cooling-is-becoming-the-data-center-standard

- https://www.foxbusiness.com/technology/google-strikes-major-nuclear-power-deal-fuel-ai-data-centers-50-megawatt-capacity

- https://www.cnet.com/tech/services-and-software/amazon-and-google-sign-nuclear-energy-deals-as-ai-power-demands-surge/

- https://trellis.net/article/amazon-google-meta-and-microsoft-go-nuclear/

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/oct/15/google-buy-nuclear-power-ai-datacentres-kairos-power

- https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/nov/19/three-mile-island-nuclear-loan-microsoft-datacenter