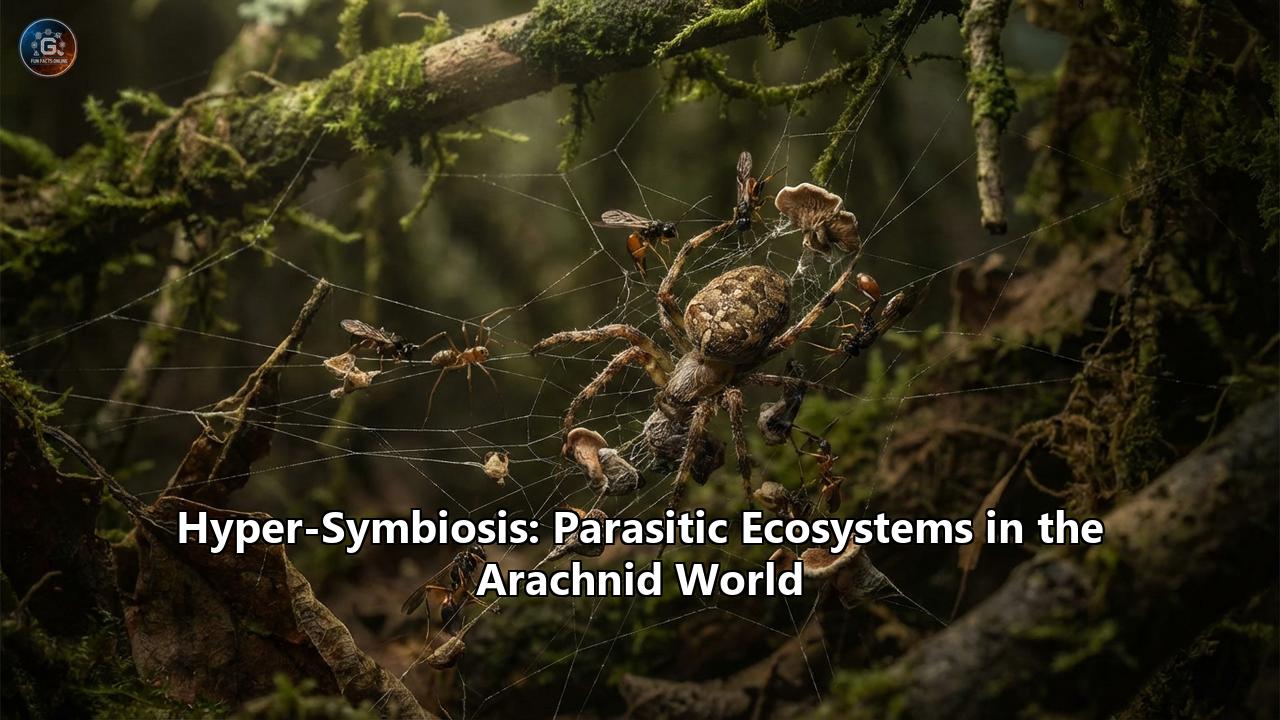

In the shadowed corners of the undergrowth, beneath the bark of rotting logs, and suspended in the silken architecture of the canopy, a silent war is being waged. It is a conflict of microscopic proportions but epic complexity, a Russian nesting doll of biological interactions where the concept of "individual" dissolves into a "colony." We often view arachnids—spiders, scorpions, ticks, and mites—as solitary predators or pests. We see the wolf spider hunting in the grass or the orb-weaver waiting patiently in its web. But look closer, through the lens of high-magnification macro-ecology, and these creatures reveal themselves to be not just hunters, but landscapes.

They are mobile ecosystems, walking biological islands that support complex communities of residents. Some are distinct hitchhikers, merely using the arachnid as a bus; others are thieves, stealing food from the host’s table; and some are masters of physiological hijacking, rewriting the genetic and behavioral code of their hosts. But the complexity does not stop there. These parasites have their own parasites—hyperparasites—and those hyperparasites may carry symbiotic bacteria that alter the entire chain of command.

This is the world of Hyper-Symbiosis: a theoretical framework for understanding the multi-trophic, recursive, and often bizarre networks of life that exist entirely on, within, and around the arachnid form.

I. The Host as a Landscape: The Spider as a "Superhost"

To understand hyper-symbiosis, one must first reconceptualize the arachnid host. A large female Golden Silk Orb-weaver (Trichonephila) is not merely a spider; she is a geological feature to the thousands of organisms that interact with her. Her web is a city, her body a continent.

The Invisible Metropolis of the WebThe web of a large spider is a resource-rich environment that attracts more than just prey. It attracts Argyrodes, the dewdrop spiders. These tiny, silver-bodied theridiids are obligate kleptoparasites. They live in the webs of larger spiders, moving stealthily across the non-sticky threads to steal wrapped prey bundles, cut silk lines to consume the protein, and even eat the host’s egg sacs.

In the arid southwestern United States, the relationship between Argyrodes pluto and its host, the black widow (Latrodectus hesperus), reveals the first layer of this parasitic ecosystem. Argyrodes are not just nuisances; they are a tax on the host’s energy. But the Argyrodes themselves are not immune. They are prone to their own set of predators and parasites, creating a micro-food web entirely suspended in the air, independent of the ground below. The host spider’s web becomes a battleground where the "owner" is often the least active participant, merely providing the infrastructure for a bustling economy of theft and murder.

The MitescapeZoom in further, to the cuticle of the spider itself. It is a jagged terrain of hairs (setae), spines, and chitinous plates. Here, the "mitescape" flourishes. Mites (Acari) are the most diverse biological hitchhikers on Earth, and arachnids are their preferred vehicles.

The phenomenon of phoresy—one organism using another for transport—is common, but in arachnids, it reaches absurd levels of complexity. A harvestman (daddy longlegs) wandering the forest floor may carry larval erythraeid mites (Leptus spp.) attached to its legs. These larvae are parasitic, drilling into the harvestman’s leg to suck hemolymph (spider blood). However, they are temporary residents. Once engorged, they drop off to molt.

But consider the fossil record. In Baltic amber dating back 50 million years, we find evidence of this relationship frozen in time. A whirligig mite (Anystidae), a predator in its own right, was found with a planidium—the first-instar larva of a small-headed fly (Acroceridae)—attached to it. This is a rare glimpse into a "parasite on a predator on a potential parasite" chain. Acrocerid flies are typically parasitoids of spiders. The fact that one attached to a mite suggests a case of mistaken identity or a complex, multi-stage life cycle where the mite acts as a bridge to get the fly larva closer to its true spider host.

II. The Physiological Hijackers: Zombification and Bio-Engineering

The most dramatic examples of hyper-symbiosis occur when the parasite does not merely eat the host, but becomes the host, commandeering its nervous system to serve the parasite's own survival.

The Architect WaspsThe Polysphincta group of ichneumonid wasps are the premier bio-engineers of the spider world. A female wasp finds a spider, temporarily paralyzes it, and glues an egg to its abdomen. The spider recovers and continues its life, weaving webs and catching prey, unaware that the larva on its back is slowly draining its hemolymph.

For weeks, the relationship seems commensal, almost benign. But as the wasp larva prepares to pupate, it injects a chemical cocktail—likely ecdysteroid-mimicking hormones—into the spider. This triggers a specific, genetically dormant behavioral program. The spider stops building its normal capture web and instead constructs a "cocoon web"—a reinforced, minimalistic structure designed solely to protect the wasp pupa.

Once the web is finished, the spider sits in the center, and the larva consumes it entirely, leaving only a husk. The larva then spins its cocoon in the safety of the web the spider was forced to build. This is extended phenotype in action: the wasp’s genes are expressing themselves through the spider’s behavior.

The Fungus That Eats the Zombie-MakerIf the wasp is a horror movie monster, the fungus Gibellula is something far stranger. Gibellula is a genus of pathogenic fungi specialized to hunt spiders. Unlike generalist fungi that simply kill and consume, Gibellula manipulates the spider.

An infected jumping spider or cellar spider will be compelled to leave its hiding spot and climb to the underside of a leaf or a high cavern wall—a location optimal for spore dispersal. There, the spider bites down, locking itself in place, and dies. The fungus then erupts from the spider’s body, not as a shapeless mold, but as structured, colorful stalks (synnemata) that often mimic the appearance of an insect, potentially luring other predators to their doom.

But here enters the hyperparasite.

Recent research has uncovered that Gibellula itself is often victim to another fungus, Penicillium tealii. This is a fungus that does not infect spiders directly; it infects the Gibellula that is infecting the spider. In this "hyper-fungal" war, the Penicillium overgrows the Gibellula fruiting bodies, stealing the nutrients the Gibellula stole from the spider.

Imagine the layers:

- The Spider: The base resource, the "terrain."

- The Gibellula: The zombie-maker, controlling the spider’s mind and body.

- The Penicillium: The thief, consuming the zombie-maker and preventing it from reproducing.

From an ecological perspective, the Penicillium might actually be "beneficial" to the spider population by suppressing the virulent Gibellula, acting as a natural check on the zombie plague.

III. The Recursive Nightmare: Hyperparasitism in Ticks and Mites

In the world of ticks (Ixodida), blood is the currency of life. But obtaining it is dangerous; it involves finding a vertebrate host, evading immune responses, and avoiding grooming behaviors. Some ticks have found a hack: Hyperparasitism, or feeding on their own kind.

Cannibalistic PhlebotomyIn colonies of the soft tick Ornithodoros, scientists have observed a behavior termed "homovampirism." Adult males or hungry nymphs will attach not to a mammal, but to a fully engorged female of their own species. They pierce her cuticle and drink the blood she has already processed.

This is more than just cannibalism; it is a vector pathway. If the female tick carries spirochete bacteria (like Borrelia, the cause of Relapsing Fever), the hyperparasitic tick can acquire the pathogen directly from her, bypassing the vertebrate host entirely. This creates a "closed loop" transmission cycle where the disease circulates within the tick population, independent of the external world.

The Mite’s MiteThe concept of "mites on mites" is a classic biological tongue-twister ("Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite 'em, and little fleas have lesser fleas, and so ad infinitum"). In the arachnid world, this is literal.

Pseudoscorpions, tiny scorpion-like arachnids lacking tails, are famous for phoresy. They grab the legs of giant beetles or flies to hitch a ride to a new habitat. However, these pseudoscorpions are often carrying their own passengers—smaller mites that hide in the folds of their exoskeleton. And within the gut of those mites? Bacteria.

A specific example of this multi-layered transport occurs with the pseudoscorpion Nannowithius wahrmani. It lives in symbiosis with harvester ants, but to disperse, it has been recorded hitchhiking on a scorpion (Birulatus israelensis). Here we have a pseudoscorpion (Arachnid A) riding a scorpion (Arachnid B), likely carrying mites (Arachnid C), all moving together through the desert night.

IV. The Invisible Alliances: Mutualism in the Burrow

Not all "hyper-symbiotic" relationships are parasitic. Some are surprisingly cooperative, forming interspecies alliances that rival human domestication of animals.

The Bodyguard FrogDeep in the Amazon rainforest, the massive Colombian Lesserblack Tarantula (Xenesthis immanis) shares its burrow with a tiny, humming creature: the Dotted Humming Frog (Chiasmocleis ventrimaculata).

In a normal scenario, a tarantula of this size would view a frog as a snack. But Xenesthis has a specific recognition code for this frog. The tarantula allows the frog to live in its burrow, even crawling under the spider’s massive fangs for shelter. In return, the frog acts as a specialized pest control agent.

Tarantulas are plagued by small invertebrates—ants, mites, and parasitic flies—that attack their eggs and spiderlings. The massive spider is too clumsy to catch these tiny invaders. The frog, however, specializes in eating ants and flies. The spider protects the frog from snakes and large predators; the frog protects the spider’s lineage from micro-predators. This is a mutualistic symbiosis embedded within a world of parasitism.

The Bacterial Shield of the ScorpionScorpions are ancient survivors, and part of their success may be due to their internal microbiomes. Recent genomic studies on scorpions like Vaejovis smithi have revealed specific lineages of Mycoplasma bacteria living in their guts and, surprisingly, their telsons (stinger segments).

Phylogenetic analysis suggests a pattern of cospeciation—the bacteria and the scorpions have been evolving together for millions of years. Unlike pathogenic Mycoplasma in humans, these scorpion symbionts likely play a role in nitrogen recycling (allowing scorpions to survive in nutrient-poor deserts) or even in the synthesis of venom precursors. The scorpion is not just a stinging animal; it is a walking fermentation tank, reliant on its bacterial "parasites" to survive.

V. Evolutionary Implications: The Arms Race

The existence of these hyper-symbiotic networks drives evolution at a breakneck pace. This is the Red Queen Hypothesis in overdrive: every organism must constantly evolve just to stay in the same place.

- Defense: Spiders evolve tougher cuticles to stop mites; mites evolve sharper chelicerae. Spiders evolve unpredictable behavior to confuse wasps; wasps evolve more potent neurotoxins to override that behavior.

- Complexity: The pressure of parasitism drives the evolution of sociality. Some theories suggest that social spiders (who build communal webs) evolved sociality partly to form a "guard caste" that can remove parasites from the colony—a collective immune system.

- Speciation: When a parasite becomes specialized on a host, and that host splits into two species, the parasite often splits too. But in hyper-symbiosis, a split in the host (spider) forces a split in the parasite (wasp), which forces a split in the hyperparasite (wasp-parasitizing wasp). This creates a "cascade of speciation," generating biodiversity at an exponential rate.

Conclusion: The Arachnid as a World

To study "Hyper-Symbiosis" is to realize that there is no such thing as a solitary organism. An arachnid is a node in a vast, invisible network. When a tarantula walks across the forest floor, it is a mobile city:

- Carrying phoretic mites on its legs.

- Housing mutualistic frogs in its home.

- Fighting off parasitoid flies that want to turn it into food.

- Hosting gut bacteria that help it digest that food.

- And potentially carrying fungal spores that are waiting for the right trigger to turn it into a zombie.

We must stop looking at the arachnid and start looking into the ecosystem it represents. In the end, the arachnid world is not just about eight legs and venom; it is about the millions of years of negotiations, thefts, alliances, and hijackings that have allowed these creatures—and their riders—to conquer the earth.

Reference:

- https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:174175

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/43507388_Do_parasitic_flies_attack_mites_Evidence_in_Baltic_amber

- https://www.naturespot.org/family/acroceridae

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gibellula_pulchra

- https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/insects-invertebrates/gibellula-attenboroughii-ireland

- https://entospace.substack.com/p/phoresis-and-phoretic-mites