The wind in Patagonia does not blow; it scours. It is a living force, a relentless westerly gale that is born in the Pacific, shreds itself against the jagged peaks of the Andes, and then screams across the arid steppe until it crashes into the Atlantic Ocean. Here, on the southeastern edge of Argentina, where the dry earth crumbles into the sea, an ecological collision is taking place that has captivated scientists, thrilled travelers, and rewritten the rules of the wild.

It is a scene that defies the standard logic of nature documentaries. In the popular imagination, penguins are creatures of the ice, huddled against Antarctic blizzards, pursued by leopard seals and orcas. Pumas, the "ghosts of the Andes," are solitary stalkers of the mountains and high grasslands, ambushing guanacos among the scrub. They belong to different worlds: one to the freezing ocean, the other to the dusty earth.

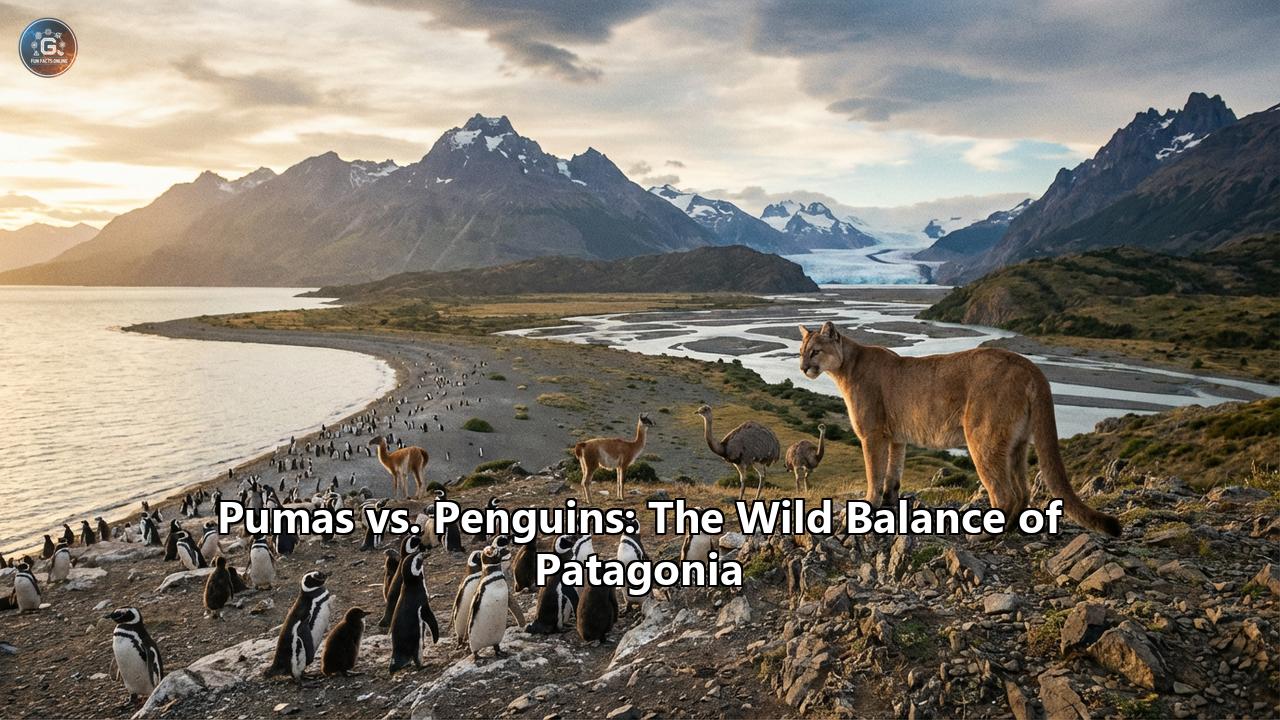

But in Monte León National Park, these two worlds do not just meet; they collide in a violent, fascinating dance of predator and prey. Here, the tawny desert cat stalks the black-and-white seabird. It is a phenomenon found almost nowhere else on Earth, a wild experiment born from the recovery of nature after a century of silence. This is the story of the wild balance of Patagonia.

The Theater of the Wild: Monte León

To understand this unique interaction, one must first understand the stage upon which it plays out. Monte León National Park is a place of stark, haunting beauty. Located in the Santa Cruz province of Argentina, it protects roughly 62,000 hectares of steppe and 40 kilometers of coastline. It is a landscape of extremes.

The steppe here is not a flat, empty table. It is a rolling sea of yellow coirón grass, punctuated by thorny calafate bushes and low, scrubby neneo plants that cling to the gravelly soil. It is a land that looks barren at first glance but is teeming with life adapted to the aridity. Herds of guanacos—wild relatives of the llama—graze on the tough grasses, their cinnamon-colored coats blending perfectly with the dusty hills. Choiques, the lesser rhea, sprint across the plains on prehistoric legs, looking like miniature ostriches.

As you move east, the steppe ends abruptly. The land falls away into the sea, carved into dramatic sandstone cliffs that glow ochre and gold in the sunrise. Tides here are immense, retreating hundreds of meters to reveal vast, glistening mudflats and rocky resting places. The most famous landmark, the Cabeza del León (Lion’s Head), is a rock formation sculpted by wind and water that resembles a sphinx-like feline gazing out over the Atlantic—a geological foreshadowing of the biological drama unfolding beneath it.

This interface—where the arid desert meets the nutrient-rich South Atlantic—is a "biogeographical ecotone," a transition zone of immense productivity. The sea here is cold, fed by the Malvinas Current, and teeming with krill, squid, and anchovies. This richness attracts the birds. Cormorants, terns, and gulls paint the cliffs white with guano. But the stars of this coastline are the Magellanic penguins.

The Commuters: Magellanic Penguins

Unlike their Antarctic cousins, Magellanic penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus) are temperate birds. They do not slide on ice; they walk on dust. Every September, roughly 60,000 of them arrive at Monte León to breed. They are commuters, splitting their lives between the open ocean and the dry land.

For a penguin, Monte León is both a sanctuary and a challenge. They come here to nest, not on the surface, but underground. The soft, clay-like soil of the coastal cliffs and the shrubby steppe is perfect for digging. A mated pair will reclaim their burrow from the previous year or excavate a new one, using their feet and beaks to carve out a shelter from the roasting sun and the freezing wind.

Walking through the penguin colony—known as a pingüinera—is a sensory assault. The first thing that hits you is the sound. It is not the cute chirping depicted in cartoons; it is a raucous, donkey-like braying. Thousands of birds call out simultaneously, a cacophony of brays, honks, and trills that serves as a GPS system, allowing mates to find each other in the chaotic sprawling city of burrows.

Then, there is the smell. It is a thick, musky scent of ammonia, rotting fish, and wet feathers. To a human nose, it is pungent; to a predator, it is a dinner bell ringing across the steppe.

Life for these penguins is a grueling marathon. They are "central place foragers," meaning they are tethered to their burrows. One parent must stay with the eggs or chicks to keep them warm and protect them from gulls and skuas, while the other walks down the beach, plunges into the surf, and swims tens of kilometers offshore to hunt. They return bloated with fish, waddling up the beach, navigating the labyrinth of bushes to regurgitate food for their young. They are awkward on land, their legs set far back on their bodies for hydrodynamic efficiency, making them stumble over roots and rocks.

For millennia, this clumsiness didn't matter much. On offshore islands, they were safe. But on the mainland, the rules are different. And at Monte León, the rules are being enforced by a predator they never evolved to fear.

The Return of the King: The Patagonian Puma

The puma (Puma concolor) is the most successful large cat in the Americas, ranging from the Canadian Yukon to the tip of the Andes. In Patagonia, they are the undisputed apex predator. These are not the elusive, ghost-like cats of the North American forests. The Patagonian puma is a beast of the open country. They are large, muscular, and bold, evolved to chase down guanacos—animals that weigh up to 120 kilograms—at high speeds.

For most of the 20th century, the puma was an enemy of the state in Patagonia. European settlers arrived in the late 1800s, bringing with them millions of sheep. To a puma, a sheep is a slow, stupid guanaco that cannot run away. The cats feasted, and in retaliation, the ranchers waged a war of extermination. Pumas were shot, trapped, and poisoned. They were driven into the most inaccessible corners of the Andes, erased from the open steppe.

But the story of Patagonia is changing. In the 1990s, the wool market collapsed. The harsh climate, overgrazing, and economic shifts led to the abandonment of massive estancias (ranches). The fences rusted; the sheep disappeared. And slowly, silently, the pumas came back.

When Monte León was converted from a sheep ranch to a National Park in 2004—thanks to the vision of conservationists like Doug and Kris Tompkins—the pumas found a paradise waiting for them. The sheep were gone, but the guanacos had returned in numbers. And on the coast, they found something else: a city of 60,000 flightless birds.

The Clash: When Cat Meets Bird

The interaction between pumas and penguins at Monte León is a fascinating study in behavioral adaptability. Pumas are generally specialists; they learn to hunt specific prey from their mothers. A puma that hunts guanacos might ignore a hare. But pumas are also opportunists, and the penguin colony represents a calorie bonanza that is hard to ignore.

Biologists studying this phenomenon have pieced together a gruesome but natural narrative. Pumas typically hunt at night or in the twilight hours. They use the low scrub of the steppe to stalk. For a penguin, whose eyes are adapted for underwater vision and whose main predators come from below or the sky, a terrestrial stalker is a nightmare.

The penguin’s defense mechanism against a land threat is simple: run to the burrow. But a penguin running is no match for a cat that can sprint at 80 kilometers per hour.

When the pumas first began targeting the colony, researchers were baffled by the body count. They would find dozens of penguin carcasses in a single morning. Often, the birds were killed but not eaten, or only the breast muscle was consumed. This behavior, known as "surplus killing," is often misunderstood as cruelty. In ecological terms, it is a response to an overabundance of prey. A predator triggered by the "chase" instinct may kill repeatedly if the prey is abundant and easy to catch, intending to cache the food for later, though they often cannot consume it all.

This predation has created a unique "landscape of fear" within the colony. Penguins, usually wary only of the shoreline where sea lions patrol, now have to watch the bushes. Yet, they continue to return. The drive to breed is stronger than the fear of predation.

The Buffet Effect: Changing Puma Society

Perhaps the most groundbreaking discovery to come out of Monte León is not that pumas eat penguins, but how the penguins are changing the pumas.

Pumas are famously solitary. Adult males are territorial and intolerant of rivals; they will fight to the death over a hunting ground. Females are equally protective of their home ranges. But in Monte León, the rules of feline society are bending.

Recent studies using GPS collars and camera traps have revealed that pumas near the penguin colony are tolerating each other in ways never seen before. The density of pumas in the park is exceptionally high—some estimates suggest it is among the highest in the world.

Why? Because the food source is so abundant and concentrated that there is no need to fight for it. The penguin colony acts like a "seasonal buffet." When the penguins are present (September to April), multiple pumas can feed from the same general area without competing. They have been seen sharing the beach, walking past one another without aggression. This "tolerance" is a behavioral shift driven entirely by resource abundance, similar to how grizzly bears congregate peacefully at a salmon run.

This has profound implications for our understanding of big cats. It suggests that their "solitary" nature is not hard-wired but is a result of resource scarcity. Give them a penguin city, and they become almost social.

The Marine-Terrestrial Nutrient Loop

The impact of this interaction extends far beyond the cats and the birds. It is reshaping the chemistry of the soil itself.

The ocean is a nutrient sink. Nitrogen and phosphorus wash off the land and settle in the sea. Getting those nutrients back onto land is difficult—usually the work of seabirds dropping guano or salmon swimming upstream. At Monte León, the pumas are acting as a biological conveyor belt.

By catching penguins—who have fed on high-calorie ocean fish—and dragging them inland to eat or cache, the pumas are transporting marine nutrients into the arid steppe. The carcasses that are left behind decompose, releasing nitrogen into the soil. Scavengers like the Andean condor, the crested caracara, and the grey fox feast on the remains. Insects thrive on the carcasses, which in turn feed smaller birds and lizards.

In a land defined by its poverty of soil, the puma-penguin connection is a fertilization event. The "bloody" work of the puma is actually fueling the bloom of the steppe grasses and the health of the entire terrestrial ecosystem.

The Human History: From Extinction to Rewilding

This wild balance is, ironically, a result of human history. To walk the trails of Monte León is to walk through layers of time.

Indigenous groups, the Aonikenk (Tehuelche), lived here for thousands of years. They were nomads, hunters of the guanaco, who lived in harmony with the predators. They left behind "chenques" (burial sites) and arrowheads in the dunes, silent testaments to a time when humans were part of the food web, not its master.

Then came the era of the estancias. The Braun family, one of the most powerful wool dynasties in Patagonia, owned the land that is now the park. For a century, the primary goal was the production of wool. This meant the removal of the puma and the fox. It was a monoculture of sheep. Interestingly, during the peak of sheep farming, the penguin colonies on the mainland were smaller. Without predators, one might think they would thrive, but human disturbance and egg harvesting kept their numbers in check.

When the Tompkins Conservation foundation purchased the land in 2001 to donate it to the Argentine state, the goal was "rewilding"—restoring the missing pieces of the ecosystem. The removal of the sheep was the first step. The removal of the fences was the second.

The return of the puma was natural, but it brought a "conservation dilemma." We created a park to protect the Magellanic penguin. But by restoring the ecosystem, we also brought back the penguin’s deadliest enemy. Park rangers and biologists had to ask a difficult question: Should they intervene?

If pumas killed too many penguins, would the colony collapse? Studies conducted by Rewilding Argentina and the National Research Council (CONICET) provided the answer. While the predation is dramatic and bloody, it is not the primary threat to the penguins. Climate change, overfishing in the Atlantic, and oil spills pose far greater risks to the species than the cats. The pumas take a toll, but the colony has remained stable. Nature, it seems, can manage its own balance better than we can.

The Visitor Experience: Into the Wind

For the modern traveler, a trip to Monte León is a journey into the raw heart of Patagonia. It is not as manicured as Torres del Paine in Chile or as famous as the Perito Moreno Glacier. It is wilder, lonelier, and more intense.

The journey usually begins in the town of Puerto Santa Cruz or Rio Gallegos. Driving along National Route 3, the asphalt ribbon that cuts through the emptiness of the steppe, the sky feels overwhelmingly big. When you turn onto the gravel road into the park, the silence descends.

A visit here is not a passive experience. The wind is a constant companion. It buffets the car, whips your hair, and tastes of salt and dust.

The Penguin Trail:The hike to the penguin colony is a pilgrimage. You walk through the steppe, the smell of the sea growing stronger with every step. Signs warn you to stay on the path—not just to protect the fragile burrows, but because this is puma country.

When you reach the boardwalks overlooking the colony, the sight is mesmerizing. Thousands of penguins stand like sentinels outside their burrows. Some are grooming, others are scolding their neighbors. You can watch the "penguin highways"—worn paths through the scrub—where commuters waddle back and forth to the sea.

If you are lucky, you might spot a grey fox trotting through the periphery, looking for a neglected egg. And if you are very lucky—or perhaps, if you have a sharp-eyed guide—you might see a shape moving in the tall grass. A twitch of a tail. A pair of amber eyes. The puma is rarely seen by the casual tourist during the day, but its presence is felt. The tension in the colony is palpable.

The Coast:Down on the beach, at low tide, the landscape turns alien. The sandstone cliffs loom high, riddled with caves that were once used by the Aonikenk. The tide pools are full of crabs, anemones, and small fish. Here, you might see the other "giants" of the coast. Southern Sea Lions haul out on the rocks, their barks competing with the penguins. In the waves, the Commerson’s dolphin—a striking black-and-white dolphin known as the "panda of the sea"—plays in the surf.

And always, there is the chance of the "impossible" photo: a puma walking on the sand, the Atlantic waves crashing behind it, a surreal juxtaposition of mountain cat and ocean.

The Broader Picture: Patagonia's Big Five

Monte León helps cement Patagonia’s reputation as one of the world’s premier wildlife destinations. Enthusiasts now talk of the "Patagonian Big Five," a list of species that rival the famous African safari animals:

- The Puma: The apex predator.

- The Guanaco: The ubiquitous herbivore and primary prey.

- The Andean Condor: The king of the skies, with a 3-meter wingspan, often seen circling over puma kills.

- The Magellanic Penguin: The charismatic commuter of the coast.

- The Huemul (South Andean Deer) or The Rhea (Choique): Depending on whether you are in the forests or the steppe.

While Torres del Paine in Chile is famous for pumas hunting guanacos against a backdrop of granite towers, Monte León offers the grittier, coastal version of this drama. It is a reminder that Patagonia is not just mountains; it is also the sea.

The Future of the Wild Coast

The story of the pumas and penguins of Monte León is a story of hope. It demonstrates that nature is resilient. If you remove the pressure—if you take away the sheep, the fences, and the guns—the wild returns. It returns with a vengeance, complex and sometimes violent, but undeniably alive.

The "conflict" between the puma and the penguin is not a problem to be solved; it is a process to be admired. It is the engine of evolution at work. The penguins that survive are the fastest, the most alert, the ones who choose the best burrows. The pumas that survive are the ones who learn to navigate the tides and the thorns.

As climate change alters the oceans, moving the fish stocks further offshore, the penguins face an uncertain future. But for now, on this lonely stretch of Argentine coast, the dance continues. The wind screams, the waves crash, the penguins bray, and the puma waits in the shadows, a golden ghost watching over its kingdom of sand and sea.

This is the wild balance of Patagonia—brutal, beautiful, and perfectly complete.

Reference:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monte_Le%C3%B3n_National_Park

- http://osu-wams-blogs-uploads.s3.amazonaws.com/blogs.dir/3439/files/2019/06/Chapter-Outline-Patagonian-Steppe.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patagonian_Desert

- https://en.wikivoyage.org/wiki/Monte_Leon_National_Park

- https://www.oneearth.org/ecoregions/patagonian-steppe/

- https://national-parks.org/argentina/monte-leon/

- https://www.tompkinsconservation.org/explore/monte-leon-national-park/

- https://www.chipchick.com/2025/03/pumas-massacred-thousands-of-penguins-in-a-park-created-to-protect-them

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sKQXy3-n2lE

- https://www.discovermagazine.com/poop-on-a-stick-tests-penguins-sense-of-smell-34530

- https://trans-americas.com/monte-leon-park-argentina-patagonia-travel/

- https://www.idealx.org/live/10-177354-pumas-penguins/

- https://www.ecocamp.travel/blog/tracking-pumas-in-torres-del-paine

- https://www.wildlifeworldwide.com/tour-reports/Patagonias_pumas_and_orcas_tour_report_22_mar_2024.pdf

- https://www.flashpackerconnect.com/blog/puma-tracking-tours-in-torres-del-paine-offer-you-a-nearly-100-chance-of-puma-spotting