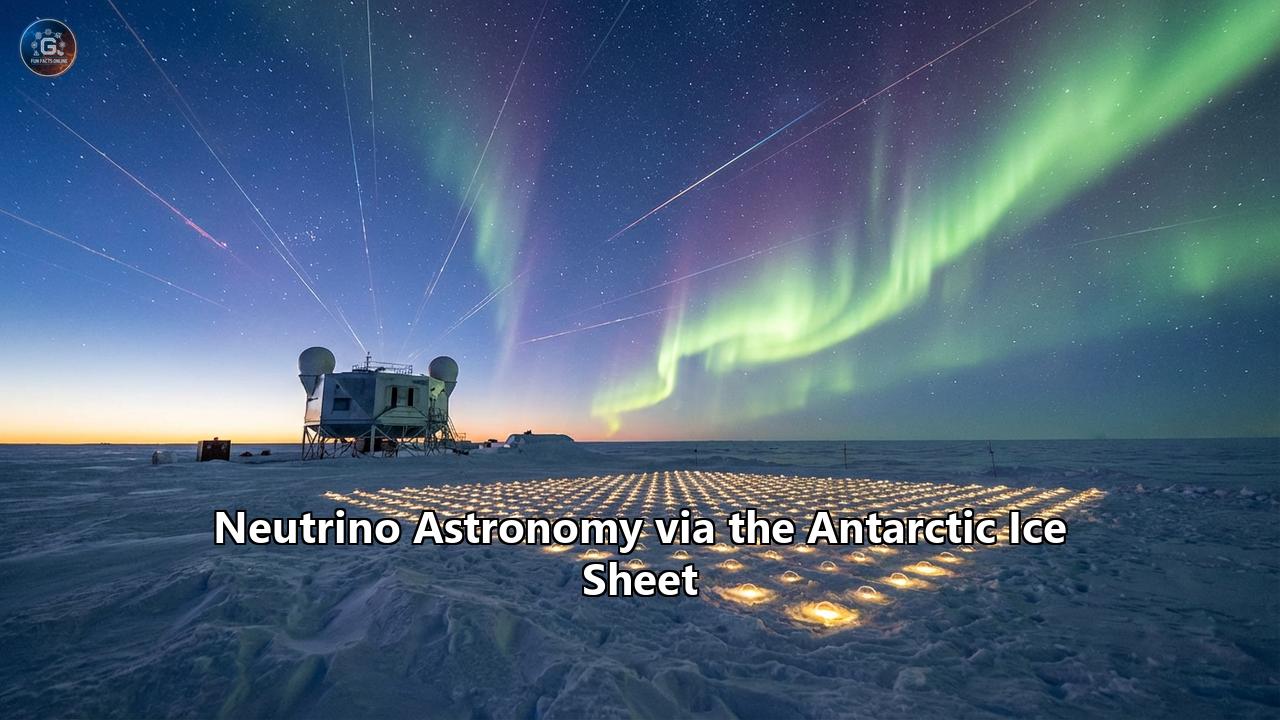

Deep within the pristine, frozen heart of Antarctica, where temperatures plunge to levels that can freeze breath instantly and the sun disappears for six months at a time, lies one of humanity’s most audacious scientific achievements. It is a telescope that does not look up at the stars with mirrors or lenses, but looks down into the ice, waiting for invisible messengers from the most violent corners of the cosmos. This is the story of Neutrino Astronomy via the Antarctic Ice Sheet—a discipline that has turned the Earth’s most inhospitable continent into a window onto the universe’s deepest secrets.

The following comprehensive guide explores the physics, history, engineering marvels, groundbreaking discoveries, and future of this extraordinary field.

Part I: The Elusive Messenger

To understand why we build massive observatories in the ice, we must first understand the quarry: the neutrino.

1.1 The Ghost Particle

Neutrinos are often called "ghost particles" for a reason. They are the second most abundant particle in the universe (after photons), yet they are notoriously difficult to detect. Born in nuclear reactions—like those in the sun’s core, supernova explosions, or the hearts of active galaxies—neutrinos have almost no mass and no electric charge. This allows them to travel in straight lines across the universe, passing through gas, dust, planets, and stars as if they weren't there.

Every second, about 100 trillion neutrinos pass through your body. You don't feel them, and they don't stop. To a neutrino, a block of lead a light-year thick is as transparent as glass. This property makes them the ideal astronomical messenger. Unlike light, which can be blocked by dust clouds, or charged cosmic rays, which are bent by magnetic fields, neutrinos point directly back to their source. They carry information from the "engines" of the universe—black holes and neutron stars—that no other particle can escape.

1.2 The Detection Challenge

The very property that makes neutrinos valuable—their refusal to interact with matter—makes them a nightmare to detect. To catch even a handful of them, you need two things:

- A colossal target: You need enough matter that, statistically, a few neutrinos will crash into an atomic nucleus.

- A transparent medium: When that collision happens, it produces a tiny flash of light. You need a medium clear enough to see that flash from hundreds of meters away.

Water is good. But to build a detector large enough to catch high-energy astrophysical neutrinos, you need something bigger than any man-made tank. You need a cubic kilometer of material. This brings us to the bottom of the world.

1.3 The Antarctic Advantage

Antarctica offers a unique solution. The ice sheet at the South Pole is over 2,500 meters (1.5 miles) thick. It has been built up over 100,000 years, layer by layer, compressing into a solid, ultra-pure block.

- Clarity: At depths below 1,500 meters, the immense pressure squeezes out all air bubbles. The ice becomes arguably the clearest solid on Earth. Blue light can travel for hundreds of meters without being absorbed.

- Darkness: Buried a mile deep, the ice is totally dark. It is shielded from the sun and from most cosmic radiation that bombards the surface.

- Structure: Unlike liquid water in the ocean, the ice is rigid. Once you place a sensor, it stays there, allowing for precise geometric reconstruction of particle tracks.

Part II: The Physics of Frozen Light

How do you "see" a particle that is invisible? The answer lies in a phenomenon known as Cherenkov Radiation.

2.1 The Sonic Boom of Light

When a high-energy neutrino finally slams into an atom of oxygen or hydrogen in the ice, it disintegrates the nucleus and creates a shower of secondary particles. These particles (like muons, electrons, or taus) are electrically charged and travel at incredible speeds.

In a vacuum, nothing travels faster than light. But light travels slower through ice than it does through a vacuum. It is possible for these high-energy particles to travel through the ice faster than the phase velocity of light in that medium. When this happens, they emit a "shock wave" of blue light—analogous to the sonic boom created by a supersonic jet. This blue glow is called Cherenkov radiation.

2.2 Reading the Signals

The detectors buried in the ice, called Digital Optical Modules (DOMs), watch for these faint blue flashes. By recording the exact nanosecond a photon hits each sensor, computers can reconstruct the event:

- Tracks: A muon neutrino interacting with the ice produces a muon. Muons are heavy and travel long distances in straight lines, leaving a long "track" of light. These events are excellent for pointing back to a source (angular resolution < 1 degree).

- Cascades: An electron neutrino produces an electron, which scatters quickly, creating a spherical ball of light called a "cascade." These are harder to point, but excellent for measuring the total energy of the neutrino.

- Double Bangs: A tau neutrino creates a tau particle, which travels a short distance and then decays. This creates two distinct flashes (one at creation, one at decay), a "double bang" signature that is the holy grail for identifying tau neutrinos.

Part III: From AMANDA to IceCube

The road to a cubic-kilometer detector was paved with skepticism and enormous engineering challenges.

3.1 AMANDA: The Proof of Concept

In the 1990s, a pioneering group of physicists launched the Antarctic Muon And Neutrino Detector Array (AMANDA). They drilled holes using hot water and lowered strings of sensors. AMANDA proved two critical things:

- The optical properties of the deep ice were even better than expected.

- It was possible to do complex particle physics in the harshest environment on Earth.

AMANDA detected atmospheric neutrinos (those created by cosmic rays hitting Earth's atmosphere) but was too small to reliably catch the rare, high-energy "cosmic" neutrinos from deep space. A bigger net was needed.

3.2 Constructing the IceCube Colossus

IceCube was approved to transform a full cubic kilometer of ice into a detector. The construction, spanning from 2004 to 2010, was a logistical masterpiece.

- The Drill: The Enhanced Hot Water Drill (EHWD) was a 5-megawatt beast. It heated water to nearly boiling and pumped it through a high-pressure hose to melt a hole 60 cm wide and 2,500 meters deep.

- The Pace: The drillers worked in shifts, 24 hours a day. It took about 48 hours to drill a hole. Once the drill was removed, the deployment team had to lower a cable with 60 sensitive DOMs before the water in the hole froze back solid. They never lost a string to freezing.

- The Scale: In total, 86 strings were deployed, holding 5,160 sensors. The final sensor was lowered in December 2010, completing the world’s largest neutrino telescope.

Part IV: Major Discoveries & The New Era of Astronomy

Since its completion, IceCube has rewritten textbooks, validating the dream of neutrino astronomy.

4.1 The First Cosmic Neutrinos (2013)

In 2013, IceCube announced the detection of two ultra-high-energy events, affectionately nicknamed "Bert" and "Ernie." These were the first neutrinos confirmed to originate from outside our solar system. They carried energies in the PeV (peta-electronvolt) range—a million times more energetic than the neutrinos produced by the sun. This marked the official birth of high-energy neutrino astronomy.

4.2 The Rosetta Stone: TXS 0506+056 (2017)

On September 22, 2017, a single high-energy neutrino (IceCube-170922A) triggered an automated alert. Within 43 seconds, telescopes around the world swung to look at the patch of sky the neutrino came from.

They found a blazar—a supermassive black hole shooting a jet of particles directly at Earth—called TXS 0506+056. The blazar was flaring in gamma rays at the exact same time. This was the first time a specific object was identified as a source of high-energy neutrinos and cosmic rays, resolving a century-old mystery about where cosmic rays come from. It was the "Rosetta Stone" event for multi-messenger astronomy (combining light and particles).

4.3 The Glashow Resonance (2016/2021)

In 1960, physicist Sheldon Glashow predicted that an anti-neutrino with a specific massive energy (6.3 PeV) would interact with an electron in a unique way, creating a W boson via "resonance." It was a prediction that required energies far beyond any particle accelerator on Earth.

In 2021, IceCube confirmed that on December 8, 2016, it had detected this exact event. A "hydrangea" of light blossomed in the detector, releasing energy exactly consistent with Glashow’s prediction. It was a stunning confirmation of the Standard Model of particle physics using the cosmos as the accelerator.

4.4 A Neutrino Map of the Milky Way (2023)

For years, our own galaxy was a puzzle. We could see it in light, X-rays, and radio, but in neutrinos, it was surprisingly dim. The problem was "noise"—atmospheric neutrinos created by cosmic rays hitting Earth's atmosphere drowned out the signal from the galactic plane.

In June 2023, researchers used advanced machine learning (AI) to filter through 10 years of data (over 60,000 cascade events). The AI successfully separated the signal from the noise, revealing the first-ever "neutrino image" of the Milky Way. It appeared as a ghostly diffuse glow, confirming that our galaxy is a source of high-energy particle acceleration, likely from the interaction of cosmic rays with interstellar dust and gas.

Part V: Life at the Bottom of the World

Operating a telescope at the South Pole is a human challenge as much as a scientific one.

5.1 The Winterovers

While summer at the South Pole (November–February) is bustling with 150 scientists and support staff, winter is a different story. From February to October, the station is physically cut off from the world. Temperatures drop to -70°C (-100°F) and below. Fuel turns to jelly; planes cannot land.

A "skeleton crew" of about 40-50 people, known as Winterovers, stays behind. Among them are usually two IceCube operators. Their job is to keep the servers running and the detector recording. They live in 24-hour darkness for six months, seeing only the Southern Lights (Aurora Australis) and the unparalleled glory of the Milky Way overhead.

5.2 The 300 Club

To cope with the isolation, traditions have emerged. The most famous is the "300 Club."

To join, you must wait for a day when the outside temperature hits -100°F (-73°C). You heat the station's sauna to +200°F (+93°C). You sit in the heat until you can't take it anymore, then run naked (wearing only boots) out the airlock to the geographic South Pole marker, circle it, and run back. The temperature differential is 300 degrees. It is a brutal, freezing, exhilarating rite of passage that bonds the winter crew together.

Part VI: The Future – IceCube-Gen2

Science does not stand still. The success of IceCube has paved the way for an even larger successor: IceCube-Gen2.

6.1 Ten Times the Volume

Gen2 is designed to be an order of magnitude larger than the current detector. It will instrument 10 cubic kilometers of ice. This massive increase in volume will allow scientists to:

- Detect 10 times as many high-energy neutrinos.

- Pinpoint sources with much higher precision.

- Detect even fainter sources that are currently invisible.

6.2 The Radio Array

For the absolute highest energy neutrinos (EeV scale)—those that carry the energy of a well-hit tennis ball in a single subatomic particle—optical detection isn't enough. The ice isn't clear enough over the kilometers of distance required to catch them.

Gen2 will add a massive Radio Array. It utilizes the Askaryan Effect: when ultra-high-energy neutrinos crash into the ice, the resulting particle shower emits a pulse of coherent radio waves. Radio waves travel much further in ice than light. By burying radio antennas shallowly in the ice over a huge area (500 square kilometers), Gen2 will listen for these radio "clicks," opening up the highest energy frontier in the universe.

6.3 Timeline

The IceCube Upgrade (7 new, densely packed strings) is already underway, serving as a technology pathfinder. The full Gen2 construction is expected to begin later in the decade, taking about 10 years to complete. It ensures that the South Pole will remain the capital of neutrino astronomy for decades to come.

Conclusion: A Window into the Invisible

Neutrino astronomy via the Antarctic ice sheet is a triumph of imagination. It turned a barren, frozen wasteland into a scientific instrument of unprecedented power. It has proven that with enough ingenuity, we can see the invisible.

Every time a sensor flashes in the dark ice below the South Pole, it captures a story that has traveled billions of years to reach us—a story of black holes, exploding stars, and the fundamental forces that bind the universe together. As IceCube continues its watch and Gen2 rises on the horizon, we are only just beginning to read the library of the cosmos. The ice is listening.

Reference:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SkrmqlvZRCc

- https://indico.cern.ch/event/1439855/contributions/6461638/attachments/3046016/5381992/IceCube_Gen2_European_Strategy_for_Particle_Physics_White_Paper_v3.pdf

- https://www.livescience.com/physics-mathematics/particle-physics/ghost-particle-image-is-the-1st-view-of-our-galaxy-in-anything-other-than-light

- https://icecube.wisc.edu/news/press-releases/2023/06/our-galaxy-seen-through-a-new-lens-neutrinos-detected-by-icecube/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=35YUzuhadOs

- https://www.universetoday.com/articles/icecube-makes-a-neutrino-map-of-the-milky-way

- https://grokipedia.com/page/300_Club

- https://www.southpolestation.com/winter/300club.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/300_Club

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/the-ceremonial-south-pole-antarctica

- https://indico.kit.edu/event/4558/contributions/17743/attachments/8181/13225/IceCube-Gen2_FIS_KAT_18102024_v3.pdf