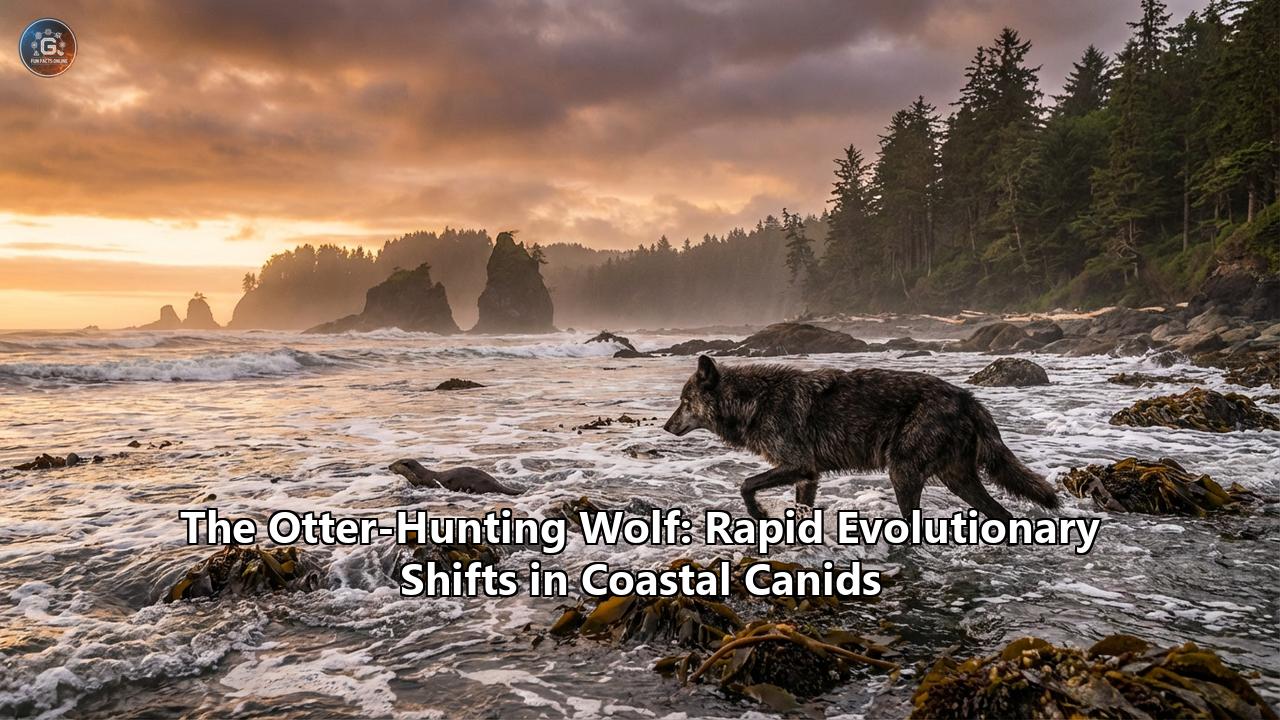

The mist clings low to the water in the fractured archipelago of Southeast Alaska, a landscape where the distinction between forest and ocean is more a suggestion than a rule. Here, the Tongass National Forest—the largest temperate rainforest on Earth—spills directly into the frigid, nutrient-rich waters of the Pacific. It is a place of ancient giants: massive Sitka spruce trees, humpback whales breaching in the channels, and brown bears patrolling the estuaries. But in recent years, a new and unexpected ghost has emerged from the treeline to claim the tide as its own.

On the isolated shores of Pleasant Island, near Glacier Bay, a biological revolution is taking place in real-time. The gray wolf (Canis lupus), the quintessential icon of the terrestrial wilderness, the phantom of the timber, has turned its golden gaze toward the sea. In a span of less than a decade, a specific population of wolves has undergone a behavioral shift so rapid and so profound that it challenges our fundamental understanding of predator adaptability. They have decimated their traditional prey and, rather than starving, have turned to a creature that no wolf was supposed to hunt as a primary food source: the sea otter.

This is not merely a story of survival; it is a glimpse into the gears of evolution turning at breakneck speed. It is a saga of ecological cascades, ancient indigenous knowledge, toxic legacies, and the fluid boundary between the land and the deep. This is the story of the otter-hunting wolf.

Part I: The Siege of Pleasant Island

To understand the magnitude of this shift, we must first understand the stage upon which it played out. Pleasant Island is a rugged, 20-square-mile landmass separated from the Alaskan mainland by the icy, turbulent waters of Icy Strait. For centuries, it was a biological fortress, lush with vegetation and supporting a healthy population of Sitka black-tailed deer.

In 2013, a small group of wolves swam the channel from the mainland. This in itself was not unusual; wolves are strong swimmers, capable of crossing miles of open water. But these colonizers found a paradise. The island was a deer nursery with no resident predators. The wolves did what apex predators do: they feasted. They reproduced. The pack grew, and the deer population began to plummet.

By 2015, the biological bill came due. The deer population on Pleasant Island had crashed. Historical ecological models—and common sense—dictated what should happen next. Having exhausted their food source, the wolves should have either starved, fought each other to the death, or swum back to the mainland in search of better hunting grounds. It is the classic boom-and-bust cycle of predator-prey dynamics, famously observed in the moose and wolf populations of Isle Royale.

But the Pleasant Island pack did not leave. They did not starve. They stayed.

Researchers from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) and Oregon State University, monitoring the pack with GPS collars and scat analysis, watched in disbelief as the wolves’ diet underwent a transformation that was statistically staggering. In 2015, deer constituted roughly 75% of the wolves' diet. By 2017, just two years later, deer made up only 7% of their intake.

Filling the void was the sea otter.

In 2015, sea otters were a minor curiosity in the wolf’s diet, perhaps scavenged from carcasses washed ashore. By 2017, they comprised nearly 60% of the pack’s consumption. In just twenty-four months, a terrestrial hyper-carnivore had effectively become a marine mammal hunter. This was not occasional scavenging; this was a systematic, learned, and culturally transmitted shift in predation. The wolves had looked at the ocean, teeming with formidable, sharp-toothed mustelids, and decided it was a grocery store.

Part II: The Mechanics of the Hunt

Hunting a deer is a chase; hunting a sea otter is a puzzle.

Sea otters are not helpless floating plush toys. They are large mustelids, closely related to wolverines, capable of weighing nearly 100 pounds. They possess powerful jaws capable of crushing clams and sea urchins, and they are armed with sharp teeth and claws. More importantly, they live in the water. A wolf in the ocean is slow, vulnerable, and out of its element. A sea otter in the water is an acrobat.

So how does a wolf catch an otter?

The Pleasant Island wolves developed a strategy of ambush and patience that relied on the tides. They learned to patrol the intertidal zone—the rocky, slick no-man's-land exposed at low tide. Sea otters often haul out onto these rocks to rest or conserve heat. The wolves, moving with the silent, ghost-like stealth of their forest ancestors, would creep through the kelp-strewn rocks.

Researchers have documented wolves waiting for hours, watching for an otter to distance itself just a few meters too far from the safety of the deep water. When the moment was right, the attack was explosive. The wolf would rush the gap, cutting off the otter's retreat to the ocean.

But they didn’t stop at the shoreline. GPS data and eyewitness accounts began to confirm even more audacious behavior: wolves swimming into the water to engage otters. While a wolf cannot outswim an otter, they can herd them, or catch them in shallow inlets where the otter’s maneuverability is limited.

This behavior is a prime example of behavioral plasticity—the ability of an organism to change its behavior in response to changing environmental conditions. It is the first step in the evolutionary process. While their genes had not yet changed, their culture had. The older wolves taught the pups not to track hoofprints in the moss, but to watch the bobbing heads in the kelp beds.

*Part III: The Evolutionary Ghost — Canis lupus ligoni---

While the diet shift on Pleasant Island was sudden, the wolves of this region were already biologically primed for a life on the edge of the sea. These are not the massive timber wolves of the Yukon or the buffalo-hunters of the Great Plains. These are the Alexander Archipelago wolves (Canis lupus ligoni), a subspecies (though taxonomically debated) distinct to Southeast Alaska.

Smaller, darker, and more compact than their interior cousins, these "rainforest wolves" have evolved in isolation for thousands of years. Genetic studies suggest they are descended from a migration that occurred long before the modern gray wolf domination of North America, possibly remnants of a wave of wolves that crossed the Bering Land Bridge and were isolated by ice sheets.

They are swimmers by nature. Their range is a fractured puzzle of over 1,000 islands. To find a mate or a new territory, an Alexander Archipelago wolf must swim. They have been recorded crossing distances of up to eight miles in freezing, current-ripped waters.

In British Columbia, their counterparts are known as "Sea Wolves." These wolves are so genetically distinct from mainland wolves that they are considered by some to be in the early stages of speciation. They live with two paws in the ocean, digging for clams, catching salmon, and cracking open crabs.

The Pleasant Island event, therefore, was not a freak anomaly but an acceleration of a latent potential. It was evolution pressing the "fast forward" button. The genetic hardware for marine adaptability was there; the starvation pressure on Pleasant Island just installed the software update.

Part IV: The Toxic Trap

There is a dark twist to this tale of survival.

In 2020, a female wolf from the Pleasant Island pack, known to researchers as Wolf 202006, was found dead. She was emaciated, having lost a third of her body weight. Her death was a mystery. She was young, the pack was successfully hunting otters, and there were no signs of injury or typical disease.

When researchers analyzed her tissues, they found the culprit. Her liver contained lethal levels of mercury.

The ocean is not just a pantry; it is a sink. Industrial pollution, coal-burning emissions, and mining runoff travel through the atmosphere and settle into the world’s oceans. There, mercury is converted by bacteria into methylmercury, a potent neurotoxin that bioaccumulates.

It starts with the plankton, which are eaten by filter feeders like clams and mussels. Sea otters eat the clams and mussels by the truckload—up to 25% of their body weight a day. The mercury that was diluted in the water becomes concentrated in the clam, and then super-concentrated in the otter.

When the wolf eats the otter, it inherits the toxic legacy of the entire food chain.

The wolves of Pleasant Island had swapped starvation for poisoning. The mercury levels found in the coastal wolves were some of the highest ever recorded in the species—orders of magnitude higher than their interior counterparts who eat moose or caribou. Mercury attacks the nervous system; it affects reproduction, motor skills, and immune function.

This discovery adds a tragic complexity to the evolutionary narrative. The very adaptation that saved them—switching to marine prey—may be slowly killing them. It is an "evolutionary trap," a scenario where an animal’s adaptive choice leads to a maladaptive outcome due to rapid environmental changes caused by humans.

Part V: Rewiring the Ecosystem — The Trophic Cascade

The wolf’s shift to sea otters does not happen in a vacuum. It sends shockwaves through one of the most famous ecological interactions in science: the Trophic Cascade.

In the classic textbook example, the sea otter is the hero.

- Sea Otters eat Sea Urchins.

- Sea Urchins eat Kelp.

- Therefore, Sea Otters protect Kelp Forests.

Kelp forests are vital. They sequester carbon, protect coastlines from erosion, and serve as nurseries for thousands of fish species. When fur traders hunted sea otters to near-extinction in the 1800s, the urchins exploded in number, mowing down the kelp forests and creating "urchin barrens"—underwater deserts. The return of the sea otter in the 20th century allowed the kelp to return.

Enter the Wolf.

If wolves start eating sea otters in significant numbers, they are adding a fourth level to this trophic cascade.

Wolf -> Otter -> Urchin -> Kelp.Theoretically, if wolves reduce the otter population, urchins could rise again, and kelp forests could fall. However, the situation on Pleasant Island is nuanced. The sea otter population in Southeast Alaska has been exploding since their reintroduction in the 1960s. In some areas, they are so dense that they have exhausted their own shellfish resources.

In this context, the wolf may be acting as a necessary stabilizer. By predating on otters, they may prevent the otters from stripping the local bays of all shellfish, actually maintaining a balance that had been lost. We are witnessing the assembly of a "novel ecosystem"—a new food web that hasn't existed in this form for centuries, perhaps millennia.

Part VI: Indigenous Wisdom and the "Wasgo"

To the Tlingit and Haida people of the Pacific Northwest, the idea of a wolf entering the sea is not a shocking scientific discovery; it is an affirmation of ancient truth.

Oral histories and mythology of the region are rich with the concept of transformation and the fluid boundary between worlds. The Gonakadet (often associated with the "Sea Wolf" or "Wasgo" in Haida mythology) is a legendary creature, a monster of the deep that is part wolf, part orca (or whale).

In the stories, the Wasgo is a creature of immense power, capable of hunting whales and bringing wealth to those who see it. While the mythological Sea Wolf is a supernatural being, its existence in the cultural consciousness points to a deep, observational understanding of the wolf’s dual nature.

Indigenous elders have long spoken of wolves swimming between islands, scavenging the beaches, and interacting with the marine world. The western scientific "discovery" of sea wolves is, in many ways, a catching-up to knowledge that has been held in the cedar clan houses of the coast for generations.

Interestingly, there is a cultural divergence in consumption. While the wolves have turned to otters, modern Tlingit people generally do not eat sea otter meat, considering it unpalatable or culturally taboo in terms of subsistence, though the fur is highly prized and culturally significant for regalia. The wolves, unburdened by palate preferences, have found sustenance where humans have not.

Part VII: Into the Future — The Aquatic Canid?

Evolution is rarely a straight line, but it is fun to speculate where this line leads. If we fast-forward a million years, could the pressure of the coastal environment produce a true marine canid?

We have seen this movie before. Fifty million years ago, a small, deer-like hoofed mammal called Pakicetus began venturing into the water to escape predators or find food. Over millions of years, its legs shortened, its nostrils moved back, and it became the whale.

The sea wolves of British Columbia and Alaska are already showing physical changes. Some studies suggest they have slightly different dentition (teeth) suited for crushing shells rather than just shearing flesh. Their fur is distinct. Their behaviors are almost entirely marine-centric.

If the deer populations remain unstable and the sea otters remain plentiful (and if the wolves can survive the mercury), natural selection will continue to favor the best swimmers, the best breath-holders, and the best crab-crackers. We might expect to see wolves with webbing between their toes becoming more pronounced, their coats becoming oilier and denser, and their ears becoming smaller to reduce heat loss in the water.

While the "Whale-Wolf" is science fiction, the "Seal-Wolf"—a semi-aquatic scavenger and hunter—is already here.

Conclusion: The Phantom’s Lesson

The otter-hunting wolves of Pleasant Island are a testament to life's tenacity. They stripped their island bare of its "proper" food, and faced with the abyss of extinction, they turned around and plunged into the sea.

They teach us that "wildness" is not a static painting to be preserved in a museum; it is a dynamic, violent, and creative force. It breaks rules. It jumps barriers. It eats the wrong things.

But their story is also a warning. The mercury in their veins is a signal flare that no ecosystem is truly isolated from human impact. Even in the pristine fjords of Alaska, where the spruce trees loom like cathedral spires and the fog erases the world, the industrial ghosts of our civilization haunt the blood of the wild.

For now, the Phantom of the Saltwater swims on. A wolf in the waves, hunting the otter, tying the forest to the sea in a knot of blood and survival that we are only just beginning to untangle.

Reference:

- https://www.hcn.org/articles/life-lessons-from-a-coastal-wolf-pack/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IYaWmQgof4o

- https://www.worldwildlife.org/resources/explainers/wildlife-climate-heroes/sea-otters-and-kelp-a-tale-of-cute-charisma-and-otterly-amazing-climate-heroism/

- https://www.britannica.com/video/what-is-trophic-cascade/-284819

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hRGg5it5FMI

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MnL6VJ7KeHU

- https://sharkallies.org/oceans-knowledge-base/kelp-forests-urchins-and-sea-stars-a-delicate-balance

- https://www.oneearth.org/sea-otters-fight-climate-change-by-guarding-kelp-forests/

- https://www.sfu.ca/ipinch/project-components/community-based-initiatives/SHI-sea-otter-project/