An engineering marvel of the ancient world, the Roman aqueduct stands as a silent, monumental testament to the ingenuity and ambition of an empire that shaped Western civilization. For centuries, these conduits of stone and concrete, stretching across vast landscapes, carried the lifeblood of water to bustling cities, opulent baths, and verdant gardens. While their colossal arches and staggering scale have long been admired as feats of construction, a new scientific discipline, paleo-hydrology, is now coaxing these ancient stones to speak, revealing secrets of a world long past. By studying the subtle clues left behind by the very water that once flowed through them, scientists are piecing together an astonishingly detailed history of the Roman world, from its climate and environment to its economic rhythms and the daily lives of its people. This is not merely a story of engineering; it is a story of water, life, and the unraveling of mysteries encoded in stone.

The Veins of the Empire: A Feat of Engineering and Vision

Before delving into the microscopic secrets held within the aqueducts, one must first appreciate the sheer scale and brilliance of their creation. The Romans constructed these extensive water systems throughout their Republic and later Empire, bringing water from distant sources into their urban centers. Rome itself, at the height of its power in the 3rd century AD, was sustained by eleven primary aqueducts. Their combined length is estimated to be between 780 and 800 kilometers (about 485 to 497 miles), a staggering network that supplied a city of over a million people.

The genius of the Roman aqueduct system lay in its elegant simplicity: gravity. Roman engineers, using surprisingly simple surveying tools like the groma and dioptra, meticulously plotted courses that maintained a slight, continuous downward gradient from the water's source to its urban destination. This slope was critical; too steep, and the rushing water would erode the channel, while too shallow a grade would cause the flow to become sluggish and stagnant. The typical gradient was remarkably gentle, often between 1:3000 and 1:4800, meaning the channel might drop only one meter in elevation for every three or more kilometers it traveled.

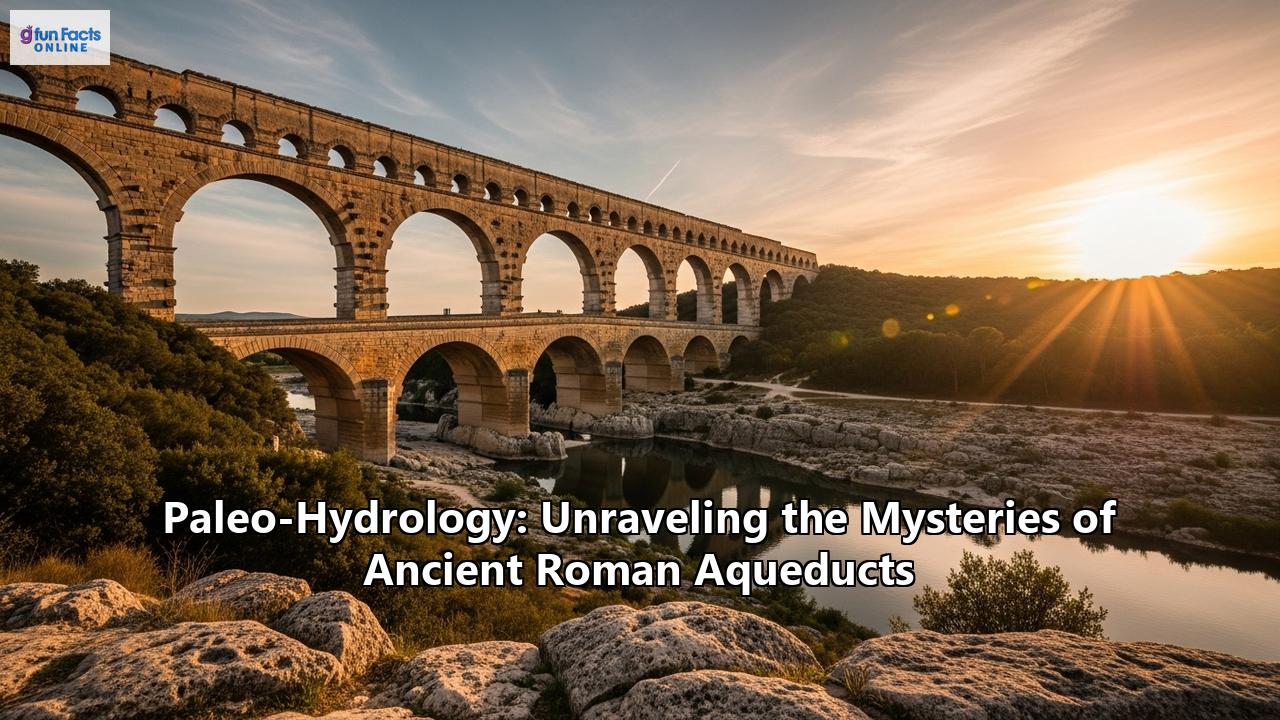

To maintain this precise gradient across the varied Mediterranean landscape, Roman engineers employed a variety of construction techniques. While the enduring image of the aqueduct is of the magnificent arched bridges, like the iconic Pont du Gard in southern France, such structures were the exception rather than the rule. They were used only when necessary to span valleys and lowlands. In fact, the vast majority—nearly 80%—of Roman aqueducts were subterranean. Engineers favored the 'cut and cover' technique, where a trench was dug, a masonry channel was built within it, and then the whole structure was covered over. This protected the water from contamination, evaporation, and potential enemy sabotage. When hills or mountains stood in the way, they were either circumvented by following the contours of the land or, if a more direct route was necessary, tunneled directly through.

The water itself was sourced primarily from pristine springs, often located high in the hills. The Romans understood that groundwater was generally purer than surface water. To maximize the yield from these springs, they would often drive tunnels into the surrounding terrain to tap into a wider network of underground water sources. In some cases, purpose-built dammed reservoirs were also used to supply an aqueduct system.

Once this carefully sourced water reached the city, it was a symbol of Roman power, wealth, and civic life. The water supplied hundreds of public fountains, latrines, and the grand public baths (thermae), which became vibrant social centers. While the wealthiest citizens could pay for a private connection to their homes, the supply to public fountains and baths always took priority. This extravagant use of water for public amenities became a defining characteristic of Roman civilization, a luxury to which cities across the empire aspired.

A Library of Stone: The Science of Aqueduct Carbonates

For all their grandeur, the aqueducts were not static monuments. They were dynamic systems that required constant attention. The hard, spring-fed water that flowed through the channels was rich in dissolved minerals, particularly calcium carbonate. As this water traveled through the open-air (though covered) channels, it would release carbon dioxide, causing the calcium carbonate to precipitate out of the solution and form thick layers of mineral deposits on the walls and floor of the aqueduct. These deposits, known scientifically as calcareous sinter or travertine, were a maintenance headache for the Romans, as they could eventually clog the channel and choke off the water flow.

What was once a nuisance for Roman engineers, however, has become an invaluable archive for modern scientists. These carbonate deposits are, in essence, a library of stone, recording the history of the water that formed them with remarkable fidelity. They function much like other natural climate proxies, such as tree rings or the layers in cave stalagmites, but often with even higher resolution. Because the water in an aqueduct flowed much faster than water dripping in a cave, these sinter layers could grow very quickly—sometimes up to a centimeter per year—creating thick deposits that offer a detailed, year-by-year, and even season-by-season, record of the past.

The field of paleo-hydrology unlocks this archive through a suite of sophisticated analytical techniques, turning these humble limestone deposits into powerful storytellers.

Stable Isotope Analysis: A Thermometer for the Past

At the heart of paleo-hydrological investigation is the analysis of stable isotopes, particularly those of oxygen (δ¹⁸O) and carbon (δ¹³C). The ratio of heavy to light oxygen isotopes in the deposited carbonate is primarily dependent on the temperature of the water at the time of its formation. Water in the aqueduct channel would warm in the summer and cool in the winter, and this seasonal temperature fluctuation is directly mirrored in the δ¹⁸O values of the carbonate layers. Colder water results in a lower δ¹⁸O value, while warmer water leads to a higher value. This creates a distinct, cyclical pattern in the isotope profile, with each cycle representing one year of the aqueduct's operation.

By meticulously sampling the carbonate and analyzing these cycles, scientists can literally count the years the aqueduct was in service between maintenance events. The carbon isotope (δ¹³C) profile often shows a similar, though sometimes more complex, cyclical pattern that can be used to corroborate the annual layering. This isotopic clock is incredibly powerful, allowing researchers to build precise chronologies for aqueduct operation, even in cases where traditional methods like radiocarbon dating are unreliable due to contamination.

Microstructure and Laminae: Reading the Seasons

This chemical fingerprint is complemented by the physical structure of the deposits. The carbonates are typically formed in beautiful, regular layers, or laminae. These often consist of alternating bands of light, dense, coarsely crystalline sparite and darker, more porous, fine-grained micrite. Studies have shown that these couplets correspond to the seasons. The dense sparite layers are generally formed in the winter during periods of higher water flow, while the more porous micrite forms in the warmer, lower-flow summer months, when biological activity (like the growth of algae and biofilms) on the channel walls is more pronounced. The combination of this visible stratigraphy with the isotope data provides a robust, cross-referenced calendar written in stone.

Trace Element Geochemistry: A Fingerprint of the Water's Journey

Beyond isotopes, scientists also analyze the trace elements trapped within the carbonate's crystal lattice. Using techniques like Laser Ablation Inductively-Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS), they can measure minute quantities of elements like magnesium, strontium, barium, and lead. The specific blend of these elements acts as a unique chemical fingerprint for the water's source. This is particularly useful for cities like Rome or Constantinople, which were supplied by multiple aqueducts. By comparing the trace element signature of carbonate deposits found in different parts of a city (for example, in the pipes of a specific bathhouse), researchers can determine which aqueduct supplied that particular area.

Furthermore, changes in the trace element profile over time can signal significant environmental events. For instance, an increase in elements associated with soil runoff could indicate deforestation or increased agricultural activity in the watershed of the aqueduct's source. This allows scientists to reconstruct not just the climate, but also how humans were interacting with and changing their landscape.

The Stories in the Stone: Case Studies from Across the Empire

The application of these paleo-hydrological techniques to aqueducts across the Roman world has revolutionized our understanding of Roman engineering, water management, and daily life. The stones are telling stories that were never recorded in any written history.

Constantinople: Managing the World's Longest Aqueduct

The water supply system of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), built in the 4th and 5th centuries AD, was the most extensive of the ancient world, stretching for an astonishing 426 kilometers. Historical records tell us this system was in use for over 700 years. When scientists first analyzed the carbonate deposits within its channels, they were faced with a puzzle. The layers of sinter they found represented, at most, about 27 years of continuous operation. This was a tiny fraction of the aqueduct's known lifespan.

The inescapable conclusion was that the aqueduct must have been meticulously and regularly cleaned. This raised a critical question: how could the Byzantines shut down the city's primary water supply for the weeks or months required for such large-scale maintenance? The answer was found in the very structure of the aqueduct itself. For a 50-kilometer stretch in the central part of the system, the aqueduct was ingeniously built with a double channel, one stacked on top of the other, running across two-story bridges. This brilliant engineering solution allowed maintenance crews to shut down and clean one channel while the other continued to supply the capital uninterrupted. The paleo-hydrological evidence of minimal sinter buildup, combined with the archaeological evidence of the double channel, paints a vivid picture of a highly sophisticated and organized water management authority in the Byzantine Empire.

The Anio Novus: Gauging the Flow to Rome

In Rome itself, studies of the Anio Novus, one of the city's major aqueducts completed in 52 AD, have rewritten our understanding of its hydraulic capacity. The Anio Novus was known even in Roman times for carrying turbid water sourced from the Anio River. Scientists studying the travertine deposits at a section of the aqueduct in Roma Vecchia used the shape and structure of the crystalline layers, known as "crystal growth ripples," to reconstruct the velocity and rate of water flow.

Their analysis revealed two key things. First, the travertine deposits had significantly reduced the internal volume of the aqueduct channel over time. This meant that the total amount of water the aqueduct could deliver was about 25% less than previous historical estimates had suggested. Second, the crystal growth patterns showed that the flow rate within the aqueduct changed systematically over time, providing a sensitive record of its operational history. This detailed hydraulic reconstruction, made possible by studying the travertine, gives us a far more accurate picture of the amount of water that actually reached the citizens of ancient Rome.

Barbegal: Clocking in at an Industrial Powerhouse

Perhaps one of the most fascinating stories to emerge from carbonate analysis comes from the Barbegal mill complex in southern France. This remarkable site, dating to the 2nd century AD, is considered one of the world's first industrial complexes. It consisted of two parallel rows of eight watermills, all powered by a single aqueduct, with an estimated capacity to produce enough flour to feed a population of over 27,000 people.

For a long time, it was assumed the mills ran continuously. However, scientists analyzing the carbonate deposits that formed on the wooden components of the mills, such as the water wheels and flumes, discovered a different story. The stable isotope profiles of the Barbegal carbonates showed that the cycles were often truncated, indicating that the mills were regularly shut down for several months at a time, mostly during the late summer and autumn. Furthermore, by examining layers of deposits on replaced wooden parts, the researchers could determine the maintenance schedule. The evidence suggests that the wooden structures were replaced approximately every 5 to 10 years, a rhythm likely dictated by the rate of wood decay. This incredibly detailed insight into the operational rhythm and maintenance of an ancient industrial site would have been impossible to obtain without the paleo-hydrological record preserved in the limestone.

A Window into Climate and Society

The secrets held within the aqueduct carbonates extend beyond engineering and maintenance. They provide a high-resolution diary of the climate in which the Romans lived. The δ¹⁸O values, which track water temperature, serve as a proxy for regional air temperatures. Darker, organic-rich layers within the deposits can signal periods of heavy rainfall and increased runoff into the aqueduct's source.

Studies on the aqueduct of Nîmes, which includes the Pont du Gard, used this methodology to document the regional environment between 50 and 275 AD. The findings suggested that the climate was remarkably stable during the first three centuries AD, a period that corresponds with the height of the Roman Empire's power and stability, often referred to as the Roman Climatic Optimum. The data also hinted at changes in vegetation, possibly linked to an increase in land use and agriculture by the local population.

This link between the aqueducts and the broader society is profound. The presence of a well-maintained aqueduct system, evidenced by regular cleaning marks in the carbonate layers, suggests a stable and prosperous urban center with a well-structured civic organization. Conversely, evidence of infrequent or sloppy maintenance can indicate periods of socio-economic stress, political instability, or population decline. In this way, the aqueduct carbonates become a proxy not just for water flow, but for the very health and stability of a Roman town. The eventual decline and abandonment of these magnificent water systems across the empire are intertwined with the complex reasons for the fall of Rome itself, including political upheaval, economic collapse, and a deteriorating climate.

A Legacy in Flow

The Roman aqueducts were far more than just conduits for water. They were instruments of empire, symbols of civic pride, and the arteries that allowed Roman urban civilization to flourish. They enabled a lifestyle of public hygiene and social gathering in the grand baths that was unique in the ancient world. They supplied industries, flushed sewers, and made cities not just habitable, but extravagant.

Today, through the lens of paleo-hydrology, these ancient structures are yielding a new kind of resource: data. The humble limestone deposits, once a maintenance challenge, have become one of our most detailed archives of the Roman world. They are providing unparalleled insights into past climates, helping us to understand the environmental context of major historical events like the rise and fall of the empire. They are revealing the sophisticated strategies of Roman engineers and water managers who, 2,000 years ago, were grappling with challenges of infrastructure maintenance and sustainability that are still familiar today.

The story of paleo-hydrology and the Roman aqueducts is a powerful reminder that history is written not only in texts and artifacts, but is also encoded in the very fabric of the world around us. In the layers of a stone, in the isotopes of an element, the voices of the past can be heard. By learning to listen, we are not just unraveling the mysteries of the Romans; we are gaining a deeper understanding of the intricate dance between civilization, technology, and the environment that continues to shape our own world. The water has long since stopped flowing, but the aqueducts, in their magnificent silence, still have much to teach us.

Reference:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_aqueduct

- https://www.google.com/search?q=time+in+Rome,+IT

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/gea.21853

- https://press.uni-mainz.de/the-aqueduct-of-constantinople-managing-the-longest-water-channel-of-the-ancient-world/

- https://aithor.com/essay-examples/how-the-romans-built-the-aqueducts-and-how-it-led-to-the-collapse-of-rome-research-paper

- https://arkeonews.net/new-insights-from-researchers-about-the-worlds-longest-aqueduct/

- https://ouci.dntb.gov.ua/en/works/45qQOgM4/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257795597_Ruling_the_waters_managing_the_water_supply_of_Constantinople_ad_330-1204

- https://e-docs.geo-leo.de/entities/publication/e2d20081-3b14-4883-a6a9-545ad51ab31c

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7004096/

- https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-ancient-traditions/ancient-water-management-0021096

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326899977_The_Adaptation_of_Architecture_to_the_Climate_during_the_Roman_Period_According_to_Classical_Authors

- https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/books/edited-volume/2351/chapter/132712358/Depositional-and-diagenetic-history-of-travertine

- https://eos.org/articles/ancient-roman-aqueducts-could-spill-climate-secrets

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/252631492_Calcareous_sinter_from_ancient_aqueducts_as_a_source_of_data_in_paleoclimate_tectonics_and_hydrology

- https://ouci.dntb.gov.ua/en/works/9Gxn1JW7/

- https://www.geosciences.uni-mainz.de/publications-gul-surmelihindi/

- https://engineeringrome.org/the-aqueducts-of-ancient-rome-a-deeper-look-at-the-aqua-claudia-anio-novus-and-aqua-virgo-2/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358084533_Travertine_crystal_growth_ripples_record_the_hydraulic_history_of_ancient_Rome's_Anio_Novus_aqueduct

- https://www.livescience.com/51167-water-carried-roman-aqueduct.html

- http://www.romanaqueducts.info/aquasite/arlesb/index.html

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6124920/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/gea.22016

- https://www.mdpi.com/2225-1154/6/4/90

- https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2023-08-04-what-did-romans-do-us-aqueducts-and-art-roman-water-management

- https://www.egu.eu/news/133/waters-role-in-the-rise-and-fall-of-the-roman-empire/

- https://traj.openlibhums.org/article/3712/galley/5679/download/

- https://www.mfo.ac.uk/files/aqueductcarbonatesworkshopprogrammewithabstractspdf