Whispers from the Stone: The Enduring Symbolism of Sardinia's Neolithic "Fairy Houses"

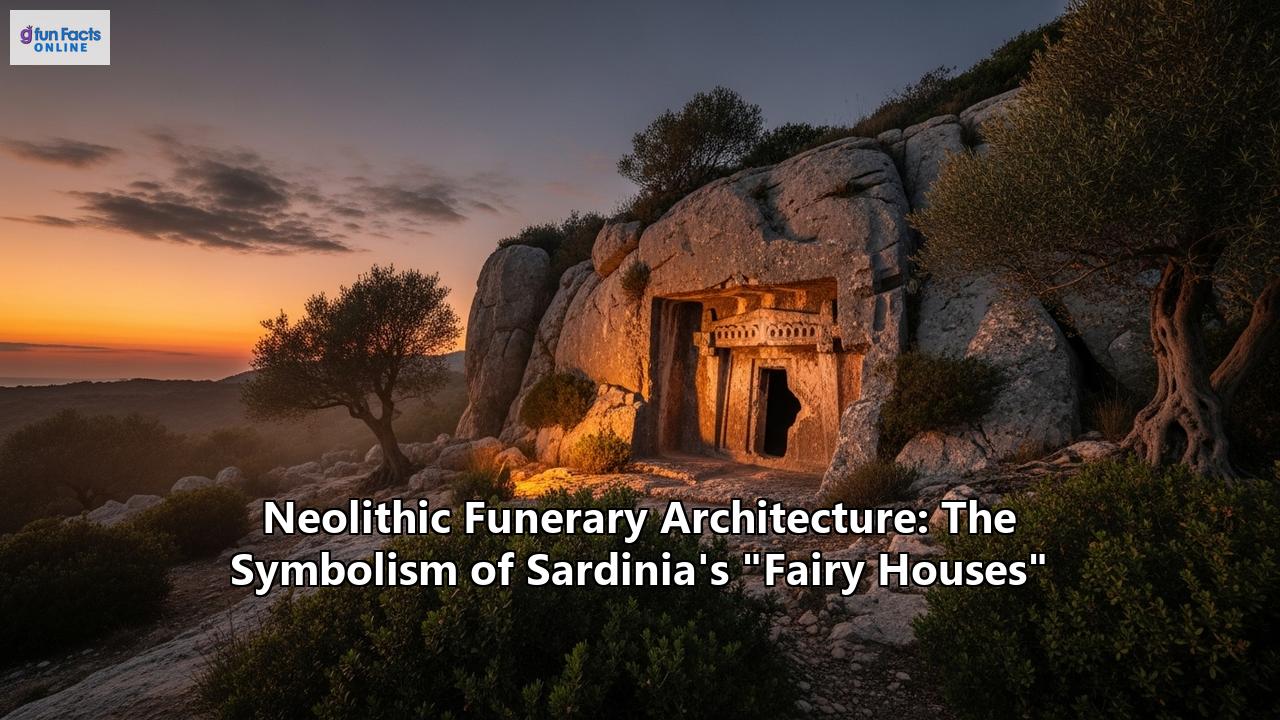

Beneath the sun-drenched landscapes and windswept shores of Sardinia lies a subterranean world, a silent testament to a sophisticated prehistoric civilization that flourished thousands of years ago. Scattered across the island like sleeping giants, more than 3,500 rock-cut tombs, known as Domus de Janas, puncture the stone, offering a profound glimpse into the Neolithic heart of the Mediterranean. To later generations who stumbled upon these diminutive, intricately carved entrances, they were not tombs, but the mystical dwellings of miniature, magical beings. They called them "Houses of the Fairies." This enduring folklore, born from a mixture of awe and forgotten history, cloaks one of Europe's most remarkable forms of funerary architecture in a veil of enchantment, inviting us to explore not just tombs, but the very worldview of the people who created them. Recently recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site in July 2025, the Domus de Janas are more than just graves; they are cosmic landscapes, architectural wombs, and enduring symbols of a belief system centered on the eternal cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

From Legend to Archaeology: Unveiling the True Inhabitants

For centuries, the true purpose of these enigmatic structures was lost to time, replaced by the rich tapestry of Sardinian myth. Legend tells of the Janas, ethereal beings who were both beautiful fairies and powerful witches. These nocturnal creatures, said to possess delicate, pale skin that could be harmed by the sun, would emerge from their stone homes only at night. Some tales describe them as skilled weavers, creating magnificent fabrics on golden looms, their songs so melodic they could enchant any mortal who heard them. Other stories cast them as arbiters of fate, visiting the cradles of newborns to determine their destiny, capable of bestowing both great fortune and terrible misfortune. This dual nature, a blend of benevolence and mischief, captured the imagination of the Sardinian people, providing a fantastical explanation for the thousands of mysterious, house-like openings carved into the island's rock faces.

It was not until the advent of modern archaeology that the "fairies" were revealed to be the ancestors of the Sardinians themselves. These rock-cut chambers were, in fact, collective burial sites, meticulously excavated by the island's prehistoric inhabitants between the Late Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age, primarily between 3400 and 2700 BCE. The majority of these tombs are attributed to the Ozieri culture, a sophisticated and largely peaceful society that represents the apex of Sardinia's Neolithic development. The name "Domus de Janas," however, has persisted, a poetic and fitting title for structures that so intimately blend the world of the living with the mystery of the dead.

The Ozieri Culture: The Master Builders of the Afterlife

To understand the Domus de Janas is to understand the Ozieri people who envisioned and built them. Flourishing from approximately 3200 to 2800 BCE, the Ozieri culture was a marvel of the Neolithic world. Theirs was a society rooted in a mixed economy of agriculture, animal husbandry, and hunting. They cultivated crops like wheat and barley and raised cattle, pigs, sheep, and goats, allowing for the growth of stable, permanent settlements.

These settlements consisted of villages made up of small stone huts, often circular, which would have supported wooden frames and thatched roofs. Unlike the later, formidable Nuragic civilizations, Ozieri villages were typically unwalled, and the scarcity of weapons found in their tombs suggests they were a remarkably peaceful people. Their society appears to have been well-organized and specialized, with evidence of early metallurgy, including the working of copper and silver, found alongside a vast array of stone tools.

What truly set the Ozieri culture apart was their exceptional artistry and their extensive trade networks. They produced highly refined pottery, with elegant, slender forms and complex, incised geometric patterns, a style so unique and advanced it was previously thought to be typical of distant Crete and the Cyclades. This connection is not coincidental. Sardinia is rich in obsidian, the volcanic glass prized throughout the ancient world for creating sharp tools. The Ozieri people were heavily involved in the obsidian trade, which brought them into contact with other Eastern Mediterranean civilizations, facilitating a vibrant exchange of goods, technologies, and, most importantly, ideas. This is evidenced by the discovery of foreign items like a copper awl from southern France and a British-style axe within the tombs, showcasing a surprisingly international reach. This cultural dynamism and spiritual depth found its ultimate expression in their complex beliefs about death and the afterlife, made manifest in the architecture of their tombs.

Houses for Eternity: The Architecture of Rebirth

The fundamental principle guiding the design of the Domus de Janas is the belief in the continuity of existence after death. These were not just repositories for the dead but eternal homes, carefully constructed to mirror the dwellings of the living. This concept of a "house for the dead" was realized with astonishing architectural detail, all painstakingly carved from the living rock using rudimentary tools like stone picks and hammers.

The tombs vary greatly in complexity, from simple, single-chamber cells to sprawling, labyrinthine complexes with over a dozen interconnected rooms. Many necropolises, like the famed Anghelu Ruju and Sant'Andrea Priu, are vast underground cemeteries, with dozens of tombs clustered together. Access to these subterranean homes could be through a vertical, well-like shaft or, more commonly, a horizontal corridor known as a dromos, which often descended via steps into an antechamber. This antechamber served as a liminal space, a threshold between the world of the living and the realm of the ancestors, likely used for collective ceremonies and funerary rituals. From here, a central chamber would open up, giving access to smaller, individual burial cells.

Inside, the level of detail is breathtaking. The Neolithic artisans carved features that explicitly mimicked the timber-and-thatch homes of their villages. Ceilings are often sculpted to represent sloping, double-pitched roofs with wooden beams and joists. Pillars and pilasters, carved from the rock, appear to support the structure. Even domestic features like hearths, often surrounded by concentric circles, were carved into the floor of the main chamber. This meticulous recreation of a domestic environment was central to their funerary beliefs, ensuring that the deceased would continue their existence in a familiar, comfortable setting, a true home for eternity.

A Lexicon of Symbols: Carving the Cosmic Journey

The walls of the Domus de Janas are a canvas of sacred art, a visual language of symbols that communicated the core tenets of Neolithic spirituality. These carvings and paintings were not mere decorations but powerful religious expressions designed to protect the deceased and facilitate their journey into the afterlife.

The Bull and the Mother Goddess: A Divine UnionThe most dominant symbol found within the tombs is the bull, or more specifically, the taurine horn or head (bucranium). Carved in relief, often framing doorways or adorning walls, the bull was a potent symbol of male strength, power, and fertility. In the context of the tomb, the bull god was seen as a protector of the dead and a symbol of regeneration. He was the divine consort to the Mother Goddess, the supreme female deity who governed the cycles of life and death. The act of burial within the rock was a symbolic return to the womb of this Earth Mother, and the bull's presence ensured the fertilization that would lead to rebirth. Statuettes of the Mother Goddess, often with exaggerated feminine features, have been found within many tombs, underscoring her central role in the promise of life beyond death.

The False Door: A Gateway to the BeyondAnother key architectural and symbolic feature is the "false door." Typically carved on the back wall of the main chamber, this motif represents a metaphysical threshold—a gateway between the world of the living and the spirit world. While mortals could not pass through it, the false door provided a symbolic passage for the soul of the deceased to journey into the afterlife. These doorways were often elaborately framed and sometimes surmounted by a series of carved bull horns, reinforcing the sacred nature of this portal.

Spirals and Concentric Circles: The Rhythms of EternitySpirals and concentric circles are recurring geometric motifs, often painted or incised near entrances or on the ceilings of the chambers. These symbols are universally understood to represent the cycles of life, death, and rebirth. The spiral, with its continuous, evolving line, can be seen as a map of the soul's journey, a representation of cosmic energy, and the cyclical nature of the seasons and life itself. When arranged in pairs, these circles are sometimes interpreted as the eyes of the Mother Goddess, watching over her children as they undergo their transformation in the tomb.

Red Ochre: The Blood of LifeA profound and recurring feature of the Domus de Janas is the extensive use of red ochre. This natural pigment, an iron oxide mineral, was used to paint the tomb walls, the symbolic carvings, and even the bodies of the deceased. The color red is universally linked to blood, the very essence of life. By covering the deceased and their eternal home in red ochre, the Neolithic people were not mourning death but actively invoking life. It was a ritual act intended to ensure regeneration and resurrection, symbolically re-infusing the body with the lifeblood needed for its rebirth in the next world.

The Funerary Ritual: A Journey Back to the Womb

The arrangement of the tombs and the artifacts found within provide clues about the funerary rituals of the Ozieri people. These were collective tombs, used over many generations. Archaeological evidence suggests two possible burial practices. One theory posits that the deceased were placed in a fetal position within the tomb, symbolizing a return to the womb for rebirth. Another theory suggests a secondary burial practice, where the body was first left to decompose in the open air until only the skeleton remained, which was then interred in the tomb.

The deceased were not sent into the afterlife empty-handed. They were buried with grave goods that reflected their life on earth: fine ceramic vessels, stone tools like obsidian arrowheads, and personal ornaments such as necklaces and bracelets. Interestingly, the very stone picks used to excavate the tomb were often left inside as part of the grave goods, imbued with the sacred value of having shaped the womb of Mother Earth. The placement of these items, along with the remains of what appear to be funerary meals consumed within the tombs, suggests a deep and ongoing connection between the living community and their ancestors.

A Tour of the Great Necropolises

While Domus de Janas are found all over Sardinia, several major necropolises stand out for their scale, complexity, and remarkable state of preservation.

The Necropolis of Anghelu Ruju: Located near Alghero, this is the largest prehistoric necropolis in Sardinia, comprising 38 individual tombs. Discovered accidentally in 1903, the tombs here showcase a wide range of designs, from simple pit tombs to complex, multi-chambered structures accessed by a dromos. Anghelu Ruju is particularly famous for its rich array of symbolic carvings, including numerous bull protomes and false doors. The sheer number of tombs and the vast collection of artifacts spanning from the Ozieri culture through the Bell Beaker and Bonnanaro cultures (c. 3200-1600 BCE) make it a crucial site for understanding the long-term evolution of Sardinian funerary practices. The Necropolis of Sant'Andrea Priu: Situated near Bonorva, this spectacular complex consists of about 20 Domus de Janas carved into a massive trachyte outcrop. It is renowned for its monumental tombs, most notably the "Tomb of the Chief" (Tomba del Capo). This colossal hypogeum is one of the largest in the Mediterranean, featuring a maze-like layout of eighteen rooms. Its interior is a masterpiece of rock-cut architecture, with pillars, pilasters, and a stunning semicircular vestibule ceiling carved to perfectly replicate the wooden-beamed roof of a hut. Sant'Andrea Priu also tells a story of cultural continuity, as several tombs, including the Tomb of the Chief, were later reused and redecorated as Christian churches in the Byzantine and medieval periods, with frescoes of apostles and biblical scenes painted over the Neolithic red ochre. The recent discovery of three new tombs at this site in 2025 continues to add to its historical richness.The Legacy in Stone: From Fairy Houses to Giants' Tombs

The tradition of creating Domus de Janas lasted for well over a millennium, but as Sardinian society evolved, so too did its funerary architecture. During the Early Bronze Age, a growing trend towards megalithism began to influence the design of these rock-cut tombs. Some Domus de Janas show clear evidence of this transition, with entrances being modified to include features that anticipate the next great phase of Sardinian monumental building: the Tombe di Giganti, or "Giants' Tombs." These later structures were massive, above-ground gallery graves with a distinctive facade of standing stones arranged in a semicircular exedra, often said to resemble the horns of a bull. The sacred symbolism of the bull, so central to the Domus de Janas, was thus carried forward, transformed into a new, monumental architectural form that would dominate the landscape of the Nuragic era.

The Domus de Janas of Sardinia are far more than ancient burial grounds. They are architectural marvels, sacred texts written in stone, and a profound expression of a deeply spiritual people. They reveal a worldview where death was not an end but a transformation, a return to the cosmic womb of the Earth Mother for the promise of rebirth. The legends of the Janas, the fairy-witches who inhabited these stone houses, serve as a beautiful, albeit unintentional, metaphor. For just as the Janas were guardians of treasure and weavers of destiny, so too are these tombs the guardians of Sardinia's deepest history, weaving a story of life, art, and belief that continues to enchant and inspire us thousands of years later. They are a timeless reminder that even in the silence of stone, the whispers of our ancestors can still be heard.

Reference:

- https://thebrainchamber.com/domus-de-janas-sacua-e-is-dolus/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pre-Nuragic_Sardinia

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domus_de_Janas

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domus_de_janas

- https://www.google.com/search?q=time+in+Provincia+di+Sassari,+IT

- https://www.saporietesoriozieri.it/en/history-of-ozieri/

- https://www.indaginiemisteri.it/en/the-ancient-symbology-of-the-spiral/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ozieri_culture

- https://kindredmedia.org/2024/06/the-spiral-an-ancient-model-useful-for-contemporary-times/

- https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/11594163

- https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100259600?print

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Sardinia

- https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-mesolithic-period/a-woman-and-a-child-from-goengehusvej/why-is-ochre-found-in-some-graves/

- https://socialscienceresearch.org/index.php/GJHSS/article/view/1692/5-Did-the-Spiral-Engravings_JATS_NLM_xml

- https://www.indaginiemisteri.it/en/the-domus-de-janas-and-the-sardinian-hypogeic-tombs/

- https://www.sardegnaturismo.it/en/itineraries/domus-de-janas-dwellings-eternity

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kp80w2PNcjw

- https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/files/25219308/Robin_CAJ_2016_Art_and_death_in_Late_Neolithic_Sardinia.pdf