For nearly forty years, the human imagination has held a distinct and vivid picture of the outer solar system. It is a picture painted in the collective consciousness by a single, heroic robotic explorer: Voyager 2. In this mental gallery, the two outermost sentinels of our sun’s domain, Uranus and Neptune, stand in stark contrast to one another.

Uranus has long been the "pale" sibling—a featureless, placid ball of aquamarine, often described as a robin’s egg blue or a soft cyan. It sits quietly on its side, a static sphere of frozen gas. Neptune, by comparison, has been the dramatic, brooding giant. In textbooks, documentaries, and the mind's eye of every space enthusiast born after 1989, Neptune is a deep, rich royal blue. It is the color of the deep ocean, fitting for a world named after the Roman god of the sea. This deep azure orb was famously punctuated by the Great Dark Spot, a storm system that seemed to stare back at us like a cosmic eye, swirling in a violently turbulent atmosphere.

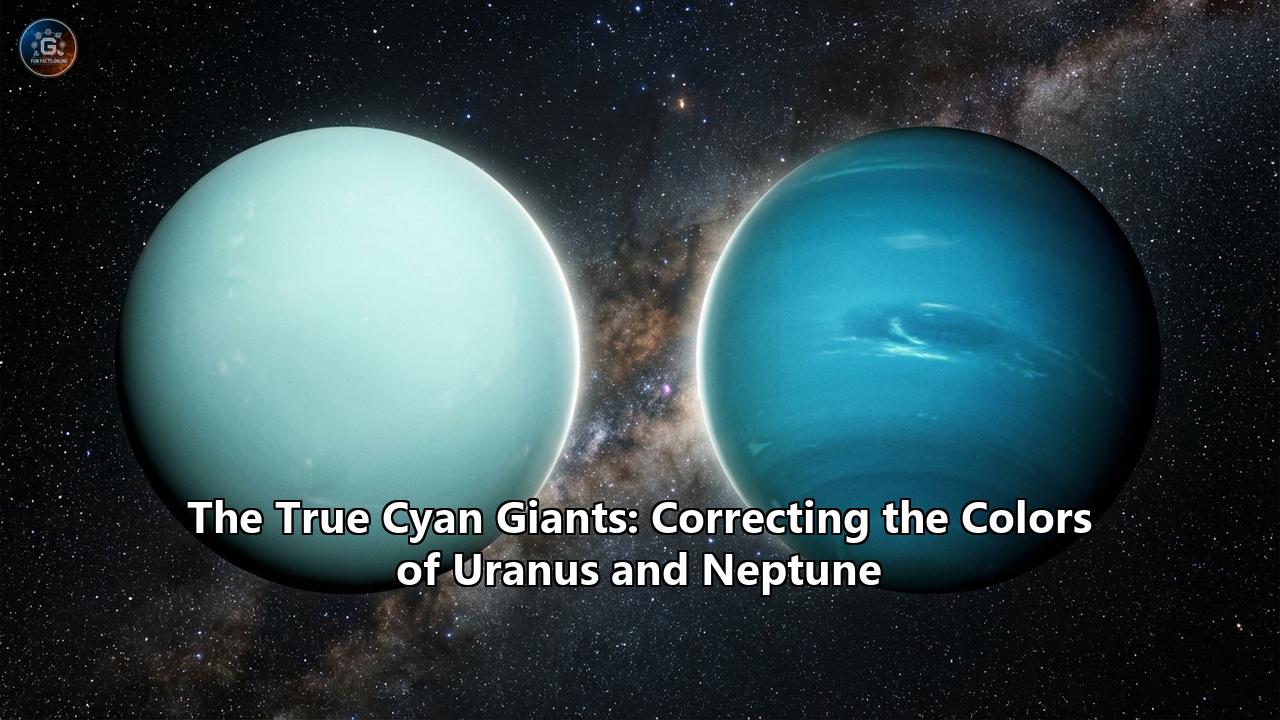

This chromatic dichotomy—the pale cyan Uranus versus the deep cobalt Neptune—became a fundamental fact of planetary science for the general public. It influenced science fiction art, planetary models in museums, and the way we visualized the formation of the solar system. It suggested a profound chemical or physical difference between these two worlds. If they are "twins"—both roughly four times the size of Earth, both composed of similar ices and gases—why would one be a ghostly green and the other a saturated, bruised blue?

The answer, revealed definitively in early 2024, is startlingly simple: They aren't.

The deep blue Neptune we have known for decades was an illusion. It was not a lie, exactly, but a misunderstanding—a scientific visualization tool that escaped the laboratory and became canon. A ground-breaking study led by Professor Patrick Irwin of the University of Oxford has stripped away the layers of image processing and historical inertia to reveal the true face of the Ice Giants.

The truth is that Neptune is not deep blue. It is, like its sibling Uranus, a pale, greenish-blue cyan. The two planets are nearly indistinguishable to the naked eye, veritable identical twins separated by a billion miles of dark vacuum. This revelation does not merely correct a color palette; it forces us to rewrite the history of our exploration, understand the limitations of our technology, and dive deep into the physics of light, atmosphere, and the very nature of human perception.

Chapter 1: The Voyager Legacy

To understand how we got the colors wrong, we must first understand how we got the images at all. The story begins with the Voyager 2 spacecraft, one of the most successful and enduring feats of human engineering. Launched in 1977, Voyager 2 was destined for the "Grand Tour," a once-in-a-lifetime alignment of the outer planets that allowed a single probe to swing past Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, using the gravity of each to slingshot to the next.

By the time Voyager 2 reached the Ice Giants, it was a tired but resilient traveler. It had survived the intense radiation belts of Jupiter and the complex orbital dance of Saturn’s moons.

The 1986 Uranus EncounterIn January 1986, Voyager 2 swept past Uranus. It was humanity's first close encounter with an Ice Giant. The data that streamed back across nearly 2 billion miles was perplexing. The planet appeared to be a blank slate. The visible light images showed a sphere that was almost completely featureless, a soft blue-green ball with very little contrast. There were no massive bands like Jupiter’s, no stunning rings like Saturn’s (though faint rings were detected).

The scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) were tasked with processing these images for public release. The cameras on Voyager, known as the Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS), did not take color photographs in the way a modern smartphone does. They were equipped with monochrome (black and white) detectors—vidicon tubes, essentially early television camera technology. To create a color image, the spacecraft would take three separate exposures of the same target through three different colored glass filters: usually blue, green, and orange (or violet).

Back on Earth, these three grayscale images were assigned their respective colors and stacked on top of one another to produce a "composite" color image. For Uranus, the resulting composite was a pale, green-blue cyan. This was relatively close to what the human eye would see, as the planet’s atmosphere was genuinely hazy and lacked high-contrast features. The public accepted this image: Uranus was the "Boring Planet."

The 1989 Neptune FlybyThree years later, in August 1989, Voyager 2 arrived at Neptune. This was the mission’s grand finale. Scientists were desperate to avoid a repeat of the "bland" Uranus encounter. They wanted to see weather, they wanted to see dynamics, and they wanted to see the storms that their models predicted might exist.

Neptune did not disappoint. As Voyager closed in, it spotted the Great Dark Spot, a massive anticyclonic storm large enough to swallow the Earth. It saw high-altitude cirrus clouds casting shadows on lower cloud decks. The winds were clocked at supersonic speeds, the fastest in the solar system. Neptune was alive.

But there was a problem with the images. Neptune is 30 times farther from the Sun than Earth. The sunlight there is 900 times dimmer than high noon on our planet. Capturing details in such low light, while the spacecraft was moving at tens of thousands of miles per hour, was a technical nightmare. The raw images were dark and low in contrast.

To visualize the atmospheric features—the bands, the clouds, the spots—the imaging team at JPL had to perform "contrast stretching." Imagine taking a photo on your phone that looks gray and dull, then using an editing app to crank up the saturation and contrast until the faint details pop out. The scientists did exactly this. They boosted the contrast to make the faint Great Dark Spot visible against the background atmosphere.

Furthermore, they used a specific combination of filters. To penetrate the methane haze and see the deeper clouds, they relied heavily on the blue and green filters, and even ultraviolet data. When they composited these images, the "stretched" contrast turned the naturally pale cyan planet into a deep, saturated blue.

The scientists knew this color was artificial. When the images were released at the press conferences in 1989, the captions explicitly stated that the color had been enhanced to bring out cloud features. One caption read: "The color has been stretched to show the subtle details of the cloud deck."

But nuance is often the first casualty of history. The public, the media, and the textbook publishers saw the stunning, deep blue marble and fell in love with it. The caption was ignored; the image became the reality. Over the next three decades, the "enhanced" false-color version of Neptune became the only version of Neptune. The "true color" caveat was forgotten, buried in the archives of the Planetary Data System, leaving us with a blue myth that would persist for 35 years.

Chapter 2: The Art of Space Imaging

The controversy over Neptune’s color opens a window into a little-known aspect of astronomy: the philosophy of image processing. There is a common accusation among conspiracy theorists that NASA "fakes" images. The reality is more complex: NASA "constructs" images, and the intent is usually scientific clarity, not deception.

The Human Eye vs. The CCDThe human eye is a biological sensor evolved to see sunlight filtered through Earth's nitrogen-oxygen atmosphere. We see a narrow band of the electromagnetic spectrum, from roughly 380 nanometers (violet) to 700 nanometers (red).

Spacecraft cameras, however, are radiometers. They measure the intensity of light. They don't "see" color; they count photons. When a spacecraft like Voyager, Hubble, or the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) looks at a planet, it captures data in specific wavelengths. Some of these are visible to humans, but many are not (Ultraviolet, Infrared, X-ray).

True Color vs. False Color- True Color: This attempts to simulate what a human astronaut would see if they were looking out the window of a spacecraft. To make a true-color image, you mix Red, Green, and Blue filtered images in the exact proportions that the human eye responds to them. This is often disappointing scientifically. True-color planets are often hazy, washed out, and low contrast.

- False Color (or Enhanced Color): This maps invisible wavelengths to visible colors or stretches the dynamic range of the image. For example, mapping an Infrared filter to the "Red" channel of a monitor might reveal heat sources. In Neptune’s case, the scientists mapped the filters in a way that deepened the blue to create contrast between the dark storms and the lighter clouds.

The problem with the 1989 Neptune images was not just the filter choice, but the dynamic range processing. The raw data showed a planet where the difference in brightness between the darkest storm and the brightest cloud was minimal. By stretching the "histogram" (the distribution of light and dark pixels), the darks became black and the lights became white. When you stretch the luminance (brightness) of a blue object, you inevitably increase its saturation.

The result was striking. The Great Dark Spot looked like a black hole in a sea of indigo. The high-altitude clouds looked like white puffy cotton against a summer sky. It was beautiful. It was dramatic. And it was scientifically useful because it allowed meteorologists to track wind speeds and cloud evolution.

However, without a constant reminder that "this is enhanced," the public perception drifted. We began to assign physical meaning to the color. We assumed Neptune had a different chemical composition than Uranus. We speculated about "deep oceans" or unique "blue ices." In reality, the difference was entirely in the digital darkroom.

Chapter 3: The Irwin Revelation

Fast forward to 2024. Professor Patrick Irwin of the University of Oxford, a veteran of planetary physics, led a team to finally set the record straight. They didn't just want to "fix" a picture; they wanted to build a comprehensive atmospheric model that could explain the observations from the last 40 years.

The MethodologyIrwin’s team didn't send a new spacecraft. Instead, they used "archaeological" data mining combined with modern high-precision observations.

- The Historic Data: They went back to the original Voyager 2 raw data files—the actual zeroes and ones beamed back in 1986 and 1989.

- The Modern Reference: They used data from the Hubble Space Telescope’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) and the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile.

The modern instruments provided something Voyager could not: a continuous spectrum. While Voyager only had discrete filters (a slice of blue, a slice of green), the MUSE instrument captures the full "rainbow" of light reflecting off the planet for every single pixel. This allowed the team to know exactly how much red, green, and blue light is actually coming from Uranus and Neptune today.

The Re-Balancing ActUsing the precise spectral data from Hubble and the VLT as a "truth anchor," the team re-processed the old Voyager images. They mathematically adjusted the Voyager filter data to match the known spectral reality.

It was like restoring an old, faded photograph (or in this case, an old, over-saturated photograph) using a modern, color-calibrated reference card.

The ResultWhen the computer finished crunching the numbers, the "new" Voyager images appeared on the screen.

- Uranus: It looked largely the same—a pale, greenish-blue ball.

- Neptune: The transformation was shocking. The deep azure vanished. In its place was a pale, washed-out, greenish-blue sphere.

Placed side by side, the two planets were nearly identical. Neptune was slightly—very slightly—bluer, but the difference was subtle, like the difference between two shades of eggshell paint. If you squinted, you couldn't tell them apart.

The "true" Neptune was still interesting. You could still see the Great Dark Spot, but it wasn't a gaping maw of darkness; it was a subtle, gray-blue bruise on the pale cyan surface. The clouds were still there, but they were softer. The planet looked like a real physical object, a ball of gas wrapped in haze, rather than a piece of CGI art.

Chapter 4: The Physics of Cyan

Why are they this color? If the deep blue was a lie, what creates the pale cyan reality? The answer lies in the chemistry of the Ice Giants.

The CompositionDespite the name "Ice Giants," these planets are not solid balls of ice. They are composed mostly of a hot, dense fluid of "icy" materials—water, methane, and ammonia—surrounding a small rocky core. Above this fluid mantle lies a thick atmosphere dominated by Hydrogen and Helium (like Jupiter and Saturn).

However, unlike Jupiter and Saturn, Uranus and Neptune have a significant amount of Methane (CH4) in their upper atmospheres—about 2% to 5% by volume.

The Methane FilterMethane is the artist of the outer solar system. It is a potent absorber of red light. When sunlight (which contains all colors of the rainbow) hits the atmosphere of Uranus or Neptune, it dives through the upper cloud layers.

- Scattering: The hydrogen and helium gas scatters the shorter wavelengths (blue) effectively, via Rayleigh scattering (the same mechanism that makes Earth’s sky blue).

- Absorption: The methane gas greedily absorbs the longer wavelengths—the red, orange, and even some yellow light.

Because the red light is absorbed and trapped, it never bounces back to our eyes. The light that does reflect back is the light that survived the journey: the blue and green wavelengths.

Green vs. BlueIf they were pure methane and hydrogen, they might look a deeper blue. However, the color is modified by aerosols. These are tiny solid or liquid particles suspended in the atmosphere—smog, essentially.

- Rayleigh Scattering (Gas): Scatters blue light strongly (Directionless).

- Mie Scattering (Aerosols/Clouds): Scatters all light equally (making things look white/grey).

The interplay between the blue-scattering gas, the red-absorbing methane, and the white-scattering haze results in the specific "cyan" or "teal" color we see. It is the color of sunlight that has been stripped of its warmth (reds) and diffused through a thick layer of photochemical smog.

Chapter 5: The Tale of Two Hazes

If both planets are made of the same stuff, why was there ever a difference at all? And why is Neptune slightly bluer in the corrected images? The Irwin study provided a detailed atmospheric model to explain this, involving three distinct layers of haze.

The Aerosol ModelThe researchers proposed a model with three main aerosol layers:

- Aerosol-1 (Deep Layer): A thick layer of mist composed of mix of hydrogen sulfide ice and photochemical haze. This is deep down, where the pressure is high.

- Aerosol-2 ( The Chromatic Layer): This is the game-changer. It is a layer of photochemical haze found in the stratosphere.

- Aerosol-3 (Upper Haze): A very thin, tenuous mist high in the atmosphere.

The key difference between Uranus and Neptune lies in Aerosol-2.

On Uranus, the atmosphere is relatively stagnant. The planet has a very low internal heat source; it is the coldest planetary atmosphere in the solar system. Because the atmosphere is sluggish, the haze particles in the Aerosol-2 layer tend to accumulate. They build up into a thicker, more opaque layer. This thick haze scatters more "white" light, which mixes with the blue from the methane to create a paler, greener hue. Think of it as adding milk to blue food coloring; it becomes a lighter, pastel cyan.

On Neptune, the atmosphere is turbulent. Neptune has a strong internal heat source (it radiates 2.6 times as much energy as it receives from the Sun). This heat drives violent weather and vertical convection. The turbulence constantly churns the atmosphere, and methane snow precipitates out more efficiently. This "weather" effectively scrubs the Aerosol-2 layer, keeping it thinner. Because the haze layer is thinner, we see deeper into the pure, methane-rich atmosphere. Less white scattering means a slightly more saturated, bluer color.

So, the subtle difference—Neptune being "true blue" and Uranus being "pale green"—is essentially a difference in air quality. Uranus is smoggy; Neptune is clear.

Chapter 6: The Chameleon Planet

One of the most fascinating puzzles solved by the 2024 study was not just the color of Neptune, but the changing color of Uranus.

For decades, astronomers noticed a strange pattern. When Uranus approached its solstice (when the pole points at the Sun), it appeared greener. When it approached its equinox (when the equator points at the Sun), it appeared bluer. This color shift was subtle, but persistent in the data record from the Lowell Observatory and Hubble.

The Solstice MysteryUranus has the most extreme axial tilt in the solar system: 98 degrees. It rolls around the Sun on its side like a bowling ball. This means that for 21 years, the north pole is bathed in continuous sunlight, while the south pole is in darkness, and vice versa.

The Irwin study utilized their new aerosol model to explain the color shift.

- The Equator (Blue Mode): The equator of Uranus is relatively clear of deep haze. It has a higher abundance of methane gas in the upper troposphere. Methane absorbs red; therefore, the equator looks bluer. During the equinox, the Sun shines directly on the equator, so we see more of this blue face.

- The Poles (Green Mode): The poles of Uranus are covered in a "Polar Hood"—a thickened cap of icy haze (likely methane ice crystals). This hood is highly reflective. It reflects more long-wavelength light (green and red) before the methane gas has a chance to absorb it. Furthermore, the actual abundance of methane gas is lower at the poles (it is frozen out or depleted by dynamics).

So, when Uranus moves toward its solstice, its pole points directly at Earth and the Sun. We are looking squarely at the "Polar Hood." We see less methane absorption (blue) and more haze reflection (white/green). The result: The planet turns green.

When the planet moves to equinox, the Sun illuminates the equator. We are looking at the methane-rich, haze-poor mid-latitudes. The result: The planet turns blue.

This mechanism—the "Chameleon Effect"—is unique to Uranus because of its insane tilt. It adds a dynamic character to a planet long thought to be static. Uranus is not just a boring blue ball; it is a breathing, shifting world that changes its skin every 42 years.

Chapter 7: Beyond the Visible

While the "true color" revelation is vital for public understanding, astronomers rarely stop at the visible spectrum. The 2024 study also relied on UV (Ultraviolet) and IR (Infrared) data, which tell a much more violent story.

The Ultraviolet ViewIn UV light, the "pale" Uranus often lights up with auroras. Because its magnetic field is tilted 60 degrees off its rotation axis, the auroras of Uranus are not neat rings at the poles; they are chaotic splotches that dance across the planet.

On Neptune, UV imaging reveals the structure of the high hazes. The "background" gas disappears, and the high-altitude distinct clouds pop out as bright white features against a black background.

The Infrared ViewThis is where the "Ice Giants" truly come alive. In the Near-Infrared, methane is so dark (it absorbs so much light) that the planet looks almost black. However, high-altitude clouds that sit above the methane layer reflect sunlight brilliantly.

In IR images, Neptune looks like a starry night sky—a dark sphere dotted with bright, transient cloud systems. These clouds are moving at 1,200 miles per hour, breaking the sound barrier.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) recently turned its golden eye toward the Ice Giants. Its infrared images of Uranus showed the ring system in shocking detail—bright, glowing loops of dust that are invisible in the Voyager optical images. It also revealed the "North Polar Cap" as a glowing white dome, confirming the haze density theories of the Irwin study.

The "True Color" is just the skin; the UV and IR views are the bones and muscle of the planet.

Chapter 8: Rethinking the Ice Giants

The correction of Neptune’s color is more than a trivial aesthetic fix. It has profound implications for how we categorize and understand planets, both in our solar system and beyond.

The "Twin" NarrativeFor years, the visual difference (Green vs. Dark Blue) drove a scientific narrative that Uranus and Neptune were fundamentally different. Scientists wasted decades looking for exotic mechanisms to explain why Neptune would have "extra" blue absorbers. Was it deep oceans of liquid diamond? Was it unique tholins (organic compounds)?

The revelation that they are the same color simplifies the science. It supports the "Twin" hypothesis: that these two planets formed in similar locations, from similar materials, and migrated out to their current positions together. The differences between them (internal heat, weather intensity) are secondary evolutionary traits, not fundamental compositional differences.

Exoplanet ImagingWe are entering the era of Direct Imaging of exoplanets. As we begin to snap photos of worlds orbiting other stars, we will be relying on single-pixel dots of light. We will have to infer their composition, weather, and "color" from spectral data—just like Irwin did.

The Neptune/Uranus mix-up serves as a cautionary tale. If we can misinterpret the color of a planet in our own backyard for 35 years, we must be incredibly careful when interpreting the "color" of a Super-Earth 50 light-years away. A "blue" exoplanet might not be a water world; it might just be a methane-rich gas giant with a thin haze layer.

The Value of Re-AnalysisThis event highlights the importance of "Data Archaeology." In the rush to launch new missions (like the Mars Rovers or Europa Clipper), we often forget the treasure trove of data sitting on hard drives from the 1970s and 80s. The Voyager data is a finite resource; we will likely not visit the Ice Giants again until the 2040s. Irwin’s study proves that we can still make major discoveries by applying new mathematical techniques to old data.

Epilogue: The Pale Green Dots

There is a certain melancholy in losing the "Blue Neptune." The deep, azure world was mysterious, beautiful, and distinct. It looked like a sapphire hanging in the void. The new Neptune—the pale, cyan ghost—is less visually striking. It looks, quite frankly, a bit like a slightly washed-out version of Uranus.

But there is beauty in the truth. The universe is not obligated to be high-contrast or saturated for our amusement. The reality of the Ice Giants is a subtle, pastel reality. They are worlds of soft hues, where the violence of the wind and the cold of the void are masked by a delicate veil of hydrocarbon mist.

The "True Cyan Giants" remind us that our perception of the universe is filtered—through our eyes, through our cameras, and through our cultural expectations. By correcting the colors of Uranus and Neptune, we have wiped the dust off the telescope lens. We see them now as they truly are: siblings, partners in the cold dark, wrapped in the same cloak of methane mist, guarding the edge of our cosmic neighborhood.

As we look forward to the proposed Uranus Orbiter and Probe mission (prioritized by the National Academies for the next decade), we can now imagine the view as we approach. We will not see a boring green ball or a cartoonish blue marble. We will see a complex, shifting world of sea-foam green and electric cyan, a world of diamond rains and supersonic winds, waiting to reveal secrets that no color filter could ever capture.

The azure myth is dead. Long live the Cyan Giants.

Reference:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hdx1Jkl5bOI

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKSWcFCMrGU

- https://earthsky.org/space/seasons-of-uranus-strange-sideways-world/

- https://www.skyatnightmagazine.com/space-science/why-neptune-blue

- https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2024-01-05-new-images-reveal-what-neptune-and-uranus-really-look-0

- https://scitechdaily.com/astronomical-illusions-new-images-reveal-what-neptune-and-uranus-really-look-like/

- https://tollbit.chron.com/news/space/article/neptune-uranus-colors-18595881.php

- https://www.krvs.org/2024-01-11/dont-look-so-blue-neptune-now-astronomers-know-this-planets-true-color

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neptune

- https://universemagazine.com/en/the-real-color-of-neptune-turns-out-to-be-not-blue/

- https://www.opb.org/article/2024/01/05/don-t-look-so-blue-neptune-now-astronomers-know-this-planet-s-true-color/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/spaceporn/comments/18zyawd/voyager_2iss_images_of_uranus_and_neptune/

- https://science.nasa.gov/gallery/neptune-gallery/

- https://ras.ac.uk/news-and-press/research-highlights/new-images-reveal-what-neptune-and-uranus-really-look

- https://www.ctpublic.org/2024-01-05/dont-look-so-blue-neptune-now-astronomers-know-this-planets-true-color

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Six_Voyager_2_images_of_Neptune_through_different_filters_(5277460787).jpg.jpg)

- https://www.skyatnightmagazine.com/news/images-uranus-neptune-true-colours