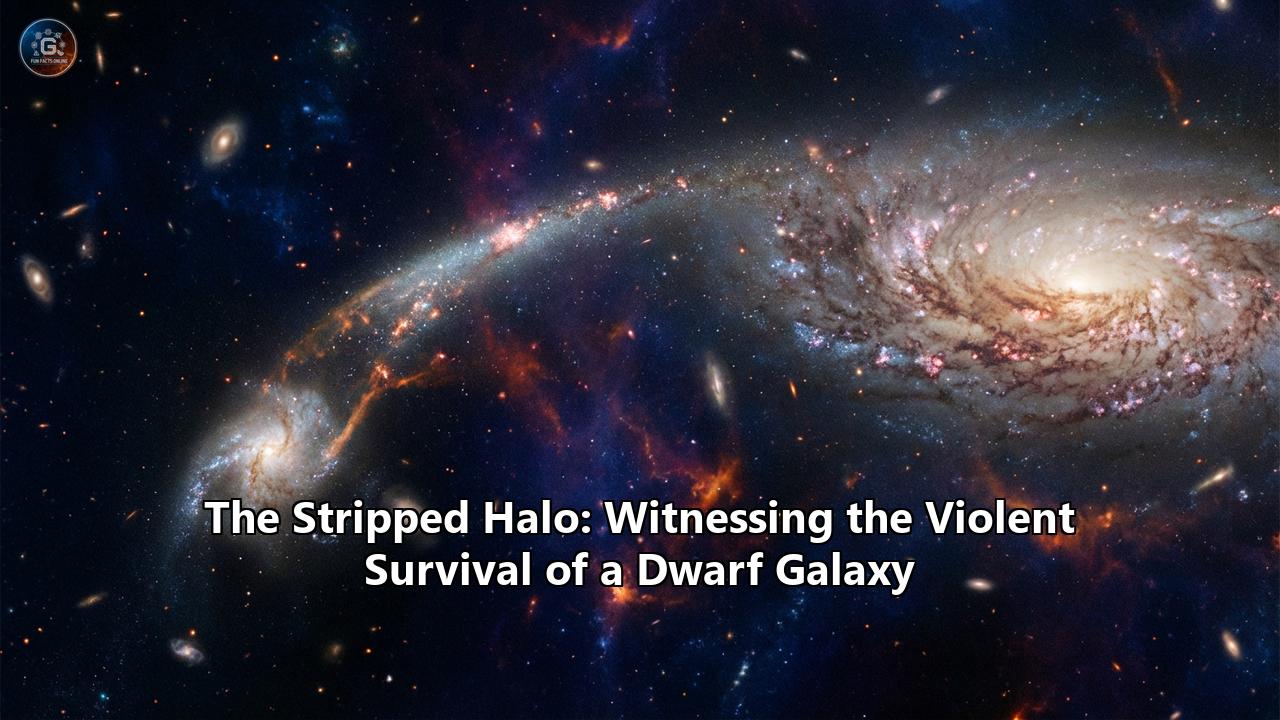

The Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) has long been a familiar smear of light in the southern sky, a satellite companion to our own Milky Way. For centuries, it appeared peaceful—a quiet neighbor merely drifting through the cosmos. But new observations from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope have shattered this serene image, revealing a chaotic history of violence, resilience, and near-destruction. The LMC is not just floating; it is a survivor of a galactic collision that stripped it of its protective shield, leaving it naked but defiant in the face of the Milky Way’s immense power.

The Cosmic Hairdryer: A Violent Encounter

The story begins with a recent, dramatic discovery that has upended our understanding of how dwarf galaxies interact with their massive hosts. Astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope directed their gaze toward the halo of the Large Magellanic Cloud—the invisible, spherical cocoon of gas and dark matter that surrounds most galaxies. In a standard model of galactic evolution, a galaxy of the LMC’s size (about 10% the mass of the Milky Way) should possess a substantial halo, a reservoir of gas fueling future star formation.

What they found, however, was a halo that had been decimated.

The LMC’s gaseous halo is roughly ten times smaller than it should be for a galaxy of its mass. It has been sheared away, blown back like smoke in a wind tunnel. The culprit? The Milky Way itself. As the LMC plunged toward our galaxy on its first-ever close approach, it slammed into the Milky Way’s own vast halo. The pressure of this collision—known as ram pressure stripping—acted like a "cosmic hairdryer," blasting away the LMC’s outer layers of gas.

Imagine driving a car down a highway at high speed and sticking your hand out the window. The force you feel pushing your hand back is ram pressure. Now, scale that up to galactic proportions. The LMC is plowing through the Milky Way’s halo at nearly a million miles per hour. The friction from this passage is so intense that it has physically stripped the dwarf galaxy of its own atmosphere, leaving a trailing wake of gas behind it like the tail of a comet.

The Anatomy of Survival

What makes this event a story of "violent survival" rather than destruction is the fact that the LMC is still here. Smaller dwarf galaxies would have been torn apart by such an encounter. Their stars would have been scattered into the Milky Way’s halo, dissolved into long stellar streams—a fate that has befallen many other satellites, such as the Sagittarius Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy.

The LMC survived because of its mass. It is a "heavyweight" among dwarfs. Its gravitational well is deep enough to hold onto its core stars and a significant portion of its dense gas, even as its outer halo was stripped away. It is a battered prizefighter, bruised and bleeding gas, but still standing in the ring.

This survival is critical for our understanding of the early universe. The LMC is thought to be a proxy for the high-redshift galaxies that populated the cosmos billions of years ago. By witnessing its survival, astronomers are getting a front-row seat to the kind of violent hierarchical merging that built the universe we see today. We are watching a galaxy being "processed"—transformed from an isolated object into a satellite, losing its independence but retaining its identity.

The Invisible Shield: Dark Matter’s Role

While the gas halo was stripped, the LMC’s survival is also a testament to its invisible backbone: dark matter. Every galaxy is embedded in a halo of this mysterious substance, which provides the gravitational glue to hold it together.

The stripping of the baryonic (visible) halo highlights the resilience of the dark halo. While ram pressure can easily push against gas (which interacts via fluid dynamics), it cannot "push" against dark matter, which interacts only via gravity. The LMC’s dark matter halo likely remains largely intact, anchoring the stars and the remaining dense gas.

This connects to another fascinating discovery regarding a different dwarf galaxy, Tucana II. In contrast to the LMC’s stripped state, Tucana II was found to have an extended dark matter halo, three to five times more massive than previously estimated. This discovery, made by tracking distant stars at the galaxy’s edge, proved that even "wimpy" ultrafaint dwarfs possess massive dark matter shields.

Comparing the two gives us a complete picture: Tucana II shows us the "pristine" state of a dwarf galaxy’s halo before it gets too close to a giant, while the LMC shows us the "stripped" aftermath of a violent collision. Together, they illustrate the life cycle of galactic halos—from extended, protective cocoons to stripped, compact remnants.

The Aftermath: Star Formation and Future Mergers

Paradoxically, the violence of the stripping process didn't kill the LMC’s ability to make stars; in some ways, it may have enhanced it. The compression of gas on the leading edge of the galaxy—the "bow shock" where it meets the Milky Way’s halo—can trigger the collapse of gas clouds, sparking new waves of star formation.

The LMC is currently a factory of new stars, notably housing the Tarantula Nebula, one of the most active star-forming regions in our Local Group. This vibrancy is a direct result of its turbulent environment. It is fighting for its life, and in doing so, it is burning brightly.

However, this survival is temporary in cosmic timescales. The LMC is losing angular momentum due to friction with the Milky Way’s halo. It is spiraling inward. In about 2 billion years, the "long embrace" will end in a total merger. The LMC will be consumed, its distinct spiral structure destroyed, and its stars added to the Milky Way’s bulk. The stripped halo we see today is the first casualty of this slow-motion digestion.

A New Era of Galactic Archaeology

The ability to witness this "stripped halo" is a triumph of modern astronomy. It requires instruments sensitive enough to detect the faint, diffuse gas of a halo and the precise movements of stars. The Hubble Space Telescope’s ultraviolet capabilities were essential for seeing the hot gas of the halo, a feat that ground-based telescopes struggle with due to Earth’s atmosphere.

This research marks a shift from studying galaxies as static "island universes" to viewing them as dynamic, evolving systems that are constantly interacting with their environment. We are no longer just taking snapshots of galaxies; we are watching movies of their lives, frame by millions-of-years-long frame.

The "stripped halo" of the Large Magellanic Cloud is more than just a scientific curiosity. It is a scar of battle. It tells us that our galaxy is not a gentle giant but a formidable force of nature, capable of stripping the atmosphere off its neighbors. And it tells us that even in the violent environment of a galaxy cluster, there is resilience. The LMC, battered and stripped, continues to shine, a beacon of survival in the turbulent dark.