The phenomenon you are asking about is one of the most spectacular and consequential events in modern glaciology. Below is a comprehensive, deep-dive article exploring the hydraulic mysteries of the Greenland Ice Sheet, written for a 2026 audience.

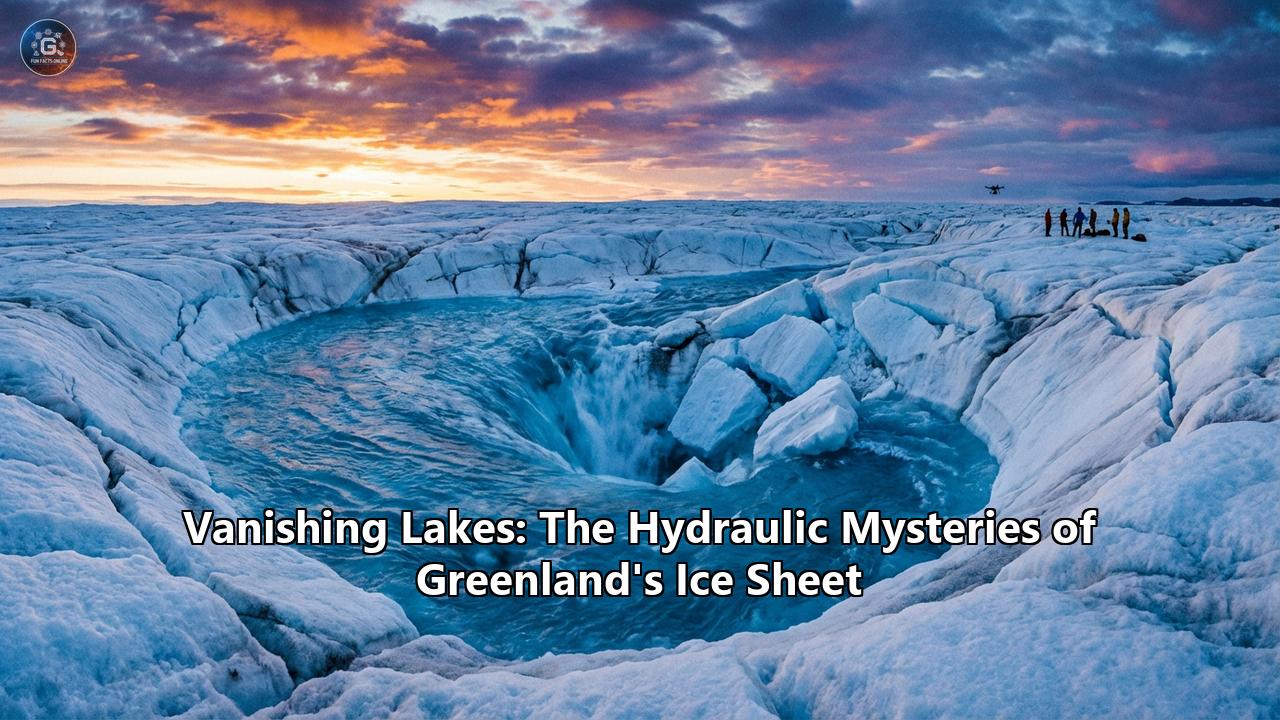

The sapphire jewels of the Greenland Ice Sheet are fleeting. In the height of the Arctic summer, thousands of supraglacial lakes—vast pools of meltwater spanning kilometers—dot the ablation zone, their deep blue hues standing in stark contrast to the blinding white of the surrounding ice. To an observer flying overhead, they appear permanent, serene features of a frozen landscape. But to the glaciologists who camp on the ice, they are ticking time bombs.

One day, a lake holding billions of gallons of water is there. The next day, it is gone.

This is not a slow evaporation or a gentle trickle. It is a violent, cataclysmic event known as rapid lake drainage. In a matter of hours, a lake the size of a city can empty entirely, punching a hole through a kilometer of solid ice and sending a Niagara-scale torrent plunging to the bedrock below. The energy released is equivalent to a tactical nuclear weapon, lifting the entire ice sheet off the ground and sliding it toward the ocean.

For decades, the mechanics of these vanishing lakes were a mystery. Today, in 2026, thanks to a convergence of satellite radar, brave field expeditions, and advanced hydraulic modeling, we finally understand the "plumbing" of the Greenland Ice Sheet. It is a story of stress, fracture, and a hidden hydraulic web that controls the fate of the northern hemisphere’s largest ice mass.

Part I: The Anatomy of a Disappearance

To understand how a lake vanishes, one must first understand the ice itself. Ice is a solid, but on the scale of a continent, it flows like a slow, viscous honey. However, when subjected to sudden stress, it behaves like glass—brittle and prone to cracking.

Every summer, as air temperatures rise, the surface of the Greenland Ice Sheet melts. This water trickles down slopes, collecting in depressions to form supraglacial lakes. Some of these lakes are small ponds; others are behemoths, covering 5 to 10 square kilometers and reaching depths of 20 meters or more. They are beautiful, but they are also heavy. A large lake can weigh millions of tons.

For years, scientists believed this sheer weight was what cracked the ice. The theory was simple: the water gets too heavy, the ice beneath it bows, and eventually, it snaps. But this "hydrostatic" theory failed to explain why some small lakes drained while larger, deeper ones nearby remained stable for the entire season.

The breakthrough came when researchers realized the trigger wasn't just the weight of the lake—it was the movement of the ice around it.

The Hydro-Fracture Mechanism

The process begins not in the lake, but near it. As meltwater streams flow across the ice surface, they often disappear into moulins—vertical shafts that carry water into the glacier’s interior. This water doesn't just vanish; it travels through englacial channels to the bed of the ice sheet.

When this initial pulse of water hits the bedrock, it acts as a hydraulic jack. It lifts the ice sheet slightly—perhaps only a few centimeters—but that is enough. This uplift creates a "bulge" in the ice surface. As the ice bends over this pressurized blister of water, the surface comes under immense tension. It stretches.

Ice is weak under tension. When the stretching force exceeds the strength of the ice, a crack opens. If this crack forms beneath a supraglacial lake, the consequences are immediate and catastrophic.

The water in the lake, previously held in check, rushes into the new fissure. This is where the physics of "hydro-fracture" takes over. Water is denser than ice. As it fills the crack, it exerts an outward pressure that is greater than the pressure of the ice trying to close the crack. The water essentially acts as a wedge, driving the fracture deeper and deeper at supersonic speeds.

A crack can propagate from the surface to the bed—a distance of over 1,000 meters (3,300 feet)—in minutes. Once the connection is made, the lake drains in a vortex of power. The flow rate can exceed the discharge of the Amazon River. In the famous "North Lake" event documented in the early 2000s, 12 billion gallons of water drained in less than two hours.

Part II: The Subglacial Hydraulic Web

Where does the water go?

This question has plagued scientists for a century. We now know that the Greenland Ice Sheet sits atop a complex, dynamic drainage system that evolves throughout the season. This subglacial world is the hidden engine of ice dynamics.

Efficient vs. Inefficient Drainage

The subglacial drainage system is not a static network of pipes. It is a shapeshifter.

In the winter and early spring, the weight of the ice sheet crushes any channels at the bed. The drainage system is "inefficient"—a distributed network of linked cavities and thin films of water. When the first summer meltwater (or a sudden lake drainage) hits this system, it has nowhere to go. The water pressure spikes violently, lifting the ice and lubricating the bedrock. This leads to the "spring speed-up," where the glacier accelerates as it slides on this high-pressure water cushion.

However, as the summer progresses and meltwater supply becomes continuous, the physics flips. The rushing water begins to melt the ice at the bed through frictional heat. It carves out large, semi-circular tunnels known as R-channels (Röthlisberger channels). These tunnels are "efficient." They can transport vast quantities of water at low pressure.

Once these channels form, the water pressure drops. The ice sheet settles back down, increasing friction with the bedrock. This is why, paradoxically, the ice sheet often slows down in late summer, even as melting is at its peak. The plumbing has become too good at its job.

The Lake Drainage "Shock"

Rapid lake drainages disrupt this orderly seasonal evolution. A draining lake delivers a massive shock pulse to the subglacial system. It overwhelms the efficient channels (if they exist) or forces open new pathways in the inefficient system.

Recent studies from 2024 and 2025 have shown that these events can trigger a "cascade." The drainage of one lake can destabilize the stress field of the surrounding ice so significantly that it triggers the drainage of neighboring lakes. This domino effect can clear large swaths of the ablation zone of water in a matter of days, sending a synchronized pulse of freshwater into the ocean.

Part III: The "Missing" Water Mystery

For years, mass balance models—the accounting ledgers of the ice sheet—couldn't account for all the water. Satellite imagery would show a lake draining, but gauges at the glacier's terminus (where the water exits into the ocean) wouldn't register a corresponding spike in outflow.

Where was the water hiding?

The answer lies in the "cryo-hydrologic" storage capacity of the ice sheet. We now understand that the ice sheet is like a sponge.

- Englacial Storage: Not all fractures reach the bed. Some arrest midway, creating vast, hidden reservoirs of water inside the ice. These "englacial aquifers" can store water year-round, insulating it from the winter cold.

- Subglacial Cavities: When a lake drains, the water can spread out laterally at the bed, filling cavities and depressions in the topography rather than flowing immediately to the ocean. This water can remain trapped for months or even years, slowly leaking out over time.

- Refreezing: As water sits in the cold interior of the ice sheet, some of it refreezes. This releases latent heat, which softens the surrounding ice. This "cryo-warming" makes the ice less viscous, allowing it to deform and flow faster, independent of basal sliding.

Part IV: The Inland Expansion – A New Threat

Perhaps the most concerning discovery of the mid-2020s is the migration of these lakes.

As the Arctic warms, the "melt line"—the elevation on the ice sheet where temperatures rise above freezing—is climbing higher. Lakes are now forming in the upper ablation zone and even the lower accumulation zone, areas that were previously too cold for liquid water.

This inland expansion poses a unique threat. The ice in the interior is colder, thicker, and stiffer. The subglacial drainage system here is almost entirely inefficient.

When lakes drain in these high-elevation regions, the water encounters a bed that has no capacity to handle it. The result is a more pronounced and sustained lubrication effect. Furthermore, the thick interior ice has a higher potential energy. If this ice begins to slide faster, the volume of mass loss could increase exponentially.

Recent satellite data has revealed "triangular fracture fields" in these inland areas—scars left by attempted lake drainages that didn't quite make it to the bed, or "failed" hydro-fractures. These features suggest that the ice sheet is trying to adapt to this new stress, but the structural integrity of the inland ice is degrading.

Part V: The Future of the Ice Sheet

The vanished lakes of Greenland are more than just a hydraulic curiosity; they are a key variable in the equation of sea-level rise.

The debate over whether basal lubrication (sliding) or surface melt (runoff) is the dominant driver of mass loss has largely been settled. It is not an "either/or" scenario; it is a feedback loop. Lubrication speeds up the ice, moving more of it into the lower, warmer elevations where it melts faster. The rapid drainage of lakes is the spark plug in this engine.

Looking ahead to the late 2020s and 2030s, models predict a nonlinear response. As lakes proliferate inland, they will access new areas of the bed. We may see the activation of "ghost" drainage networks—ancient river valleys buried beneath the ice that have not seen flowing water for ten thousand years.

The mystery of the vanishing lakes has transitioned from a puzzle of how they drain to a warning of what their drainage means. The hydraulic system of Greenland is waking up, and its veins are flowing with the meltwater of a warming world. Every vanished lake is a pulse, a heartbeat of a changing climate, signaling that the giant is on the move.

Reference:

- https://www.livescience.com/51071-how-greenland-lakes-vanish.html

- https://www.bgr.com/1940597/greenland-ice-sheets-subglacial-lake-report/

- https://climatecosmos.com/blog/greenlands-ice-sheet-is-melting-faster-than-expected-scientists-warn/

- https://en.tempo.co/read/675790/scientists-uncover-mystery-of-greendlands-vanishing-ice-lake

- https://www.sci.news/othersciences/geophysics/science-greenland-supraglacial-lakes-02876.html

- https://www.earth.ox.ac.uk/article/stress-mapping-reveals-secrets-coupled-supraglacial-lake-drainages-hydro-fracture

- https://www.lakescientist.com/research-brief-investigating-the-causes-of-rapid-supraglacial-lake-drainages/

- https://www.antarcticglaciers.org/glaciers-and-climate/changing-greenland-ice-sheet/supraglacial-hydrology-of-the-greenland-ice-sheet/

- https://www.whoi.edu/press-room/news-release/trigger-for-glacial-lake-drain/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323758169_Cascading_lake_drainage_on_the_Greenland_Ice_Sheet_triggered_by_tensile_shock_and_fracture

- https://eesm.science.energy.gov/sites/default/files/highlights/original-article/andrews-nature.pdf

- https://ladailypost.com/lanl-meltwater-from-ice-sheet-less-severe-for-sea-level-rise-than-feared/