Sunken Secrets of the Alps: The Rise of Industrial Archaeology in Mountain Lakes

The serene, crystalline waters of the great Alpine lakes, cradled by the monumental peaks of Europe, guard a history far deeper than their measured depths. For centuries, these vast bodies of water—including Lake Constance, Lake Geneva, Lake Garda, and Lake Lucerne—were not merely idyllic landscapes for poets and painters, but bustling highways of industry and commerce. Long before modern highways and rail tunnels carved through the mountains, these lakes were the lifeblood of regional economies, their surfaces plied by a vast array of vessels carrying everything from stone and timber to salt and grain. Today, a unique and challenging field of study, industrial archaeology, is plumbing these cold, dark waters to uncover the remarkably preserved remains of this bygone era, revealing a submerged heritage that is rewriting the history of European industry and transportation.

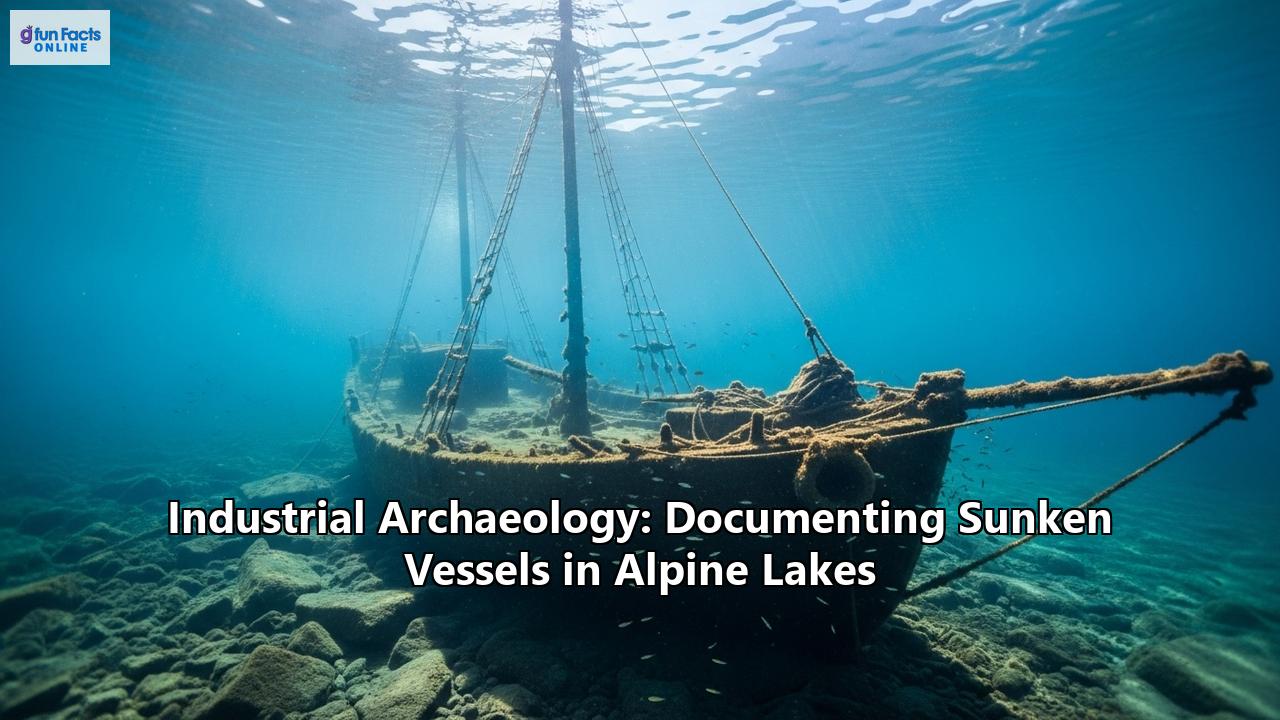

The vessels that now lie in the silent abyss of these lakes are more than just shipwrecks; they are time capsules. From majestic paddle steamers that once ferried tourists and goods in the Belle Époque to humble, workhorse barges that were the backbone of trade for centuries, each discovery offers a tangible link to the past. The exceptional preservation conditions of the cold, low-oxygen freshwater environments of these deep lakes mean that many of these wrecks are found in a state that is almost unimaginable in marine settings. Wooden hulls remain intact, masts stand tall, and in some cases, even the cargo lies undisturbed in the hold, offering archaeologists an unprecedented glimpse into the life and work of the people who relied on these waters.

This burgeoning field of underwater industrial archaeology in the Alps is being driven by technological advancements that are allowing researchers to explore these challenging environments with greater precision and safety than ever before. Teams of dedicated archaeologists, armed with side-scan sonar, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), and sophisticated 3D photogrammetry techniques, are systematically mapping the lakebeds and bringing these sunken stories back to the surface, not by raising the wrecks themselves, but by creating incredibly detailed digital models that can be studied and shared with the world. As these silent giants of the Alpine lakes are documented, they are revealing a rich and complex history of innovation, trade, and everyday life, a history that was, until recently, lost to the depths.

The Liquid Highways: A History of Industry and Transport on Alpine Lakes

The industrial history of the Alpine region is inextricably linked to its great lakes. For millennia, these bodies of water served as natural conduits for the movement of people and goods, overcoming the formidable barrier of the mountains. From the Roman era, when vessels transported stone from quarries and goods for trade, to the medieval period, when powerful families and city-states vied for control of these lucrative waterways, the lakes were central to the economic and political landscape of the region.

The advent of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century transformed the scale and nature of this lacustrine transport. The arrival of steam power heralded a new age of efficiency and reliability. The first steamboats, often with their engines and even hulls imported from industrial powerhouses like Great Britain, began to appear on the lakes in the early 1820s. These vessels, with their churning paddle wheels and plumes of smoke, revolutionized not only the transport of goods but also gave rise to a new industry: tourism. Grand paddle steamers, such as those operated by the Compagnie Générale de Navigation sur le lac Léman (CGN) on Lake Geneva, became floating monuments to the elegance and engineering prowess of the Belle Époque, ferrying thousands of tourists eager to experience the sublime beauty of the Alps.

Beneath the glamorous veneer of passenger travel, however, a more robust and essential industrial transport system thrived. On Lake Constance, for instance, a sophisticated network of train ferries was established in the mid-19th century by the railway companies of the surrounding states of Baden, Württemberg, and Bavaria. These specialized vessels could carry entire freight wagons, creating a seamless link between the burgeoning rail networks on either side of the lake and avoiding a long and arduous overland journey. This integration of water and rail transport was a critical component of the region's industrial development, facilitating the movement of everything from raw materials to manufactured goods.

The cargo transported on these lakes was as varied as the industries they served. On Lake Lucerne, barges and steamers moved vast quantities of stone from quarries around the lake, providing the building materials for the growing towns and cities of central Switzerland. In other areas, timber logged from the mountain forests was floated or barged across the lakes to sawmills and construction sites. The lakes were also crucial for the transport of agricultural products, such as wine and grain, connecting the fertile shores and hinterlands with wider markets. Even everyday goods and mail were delivered by boat, a tradition that continues to this day on Lake Geneva with its famous mailboat.

The decline of this industrial age on the lakes was gradual, brought about by the very forces of technological advancement that had once fueled its growth. The expansion of the railway network around the lakes and, later, the rise of road transport in the 20th century, offered faster and more direct routes for many goods. The once-indispensable lake transport became a slower, more cumbersome alternative. Many of the great steamships were decommissioned, and the freight barges were replaced by lorries and trains. Some vessels were simply abandoned, others were deliberately scuttled, and many met their end through storms or accidents, sinking to the lakebed to await a new era of discovery.

Voices from the Deep: Case Studies in Alpine Underwater Archaeology

The cold, dark depths of the Alpine lakes are a museum of this industrial past, and in recent years, a series of remarkable discoveries have brought the stories of these sunken vessels to light.

Lake Constance: A Fleet of Ghosts

One of the most ambitious and fruitful projects in Alpine underwater archaeology has been the recent systematic survey of Lake Constance (known as the Bodensee in German). This vast lake, bordering Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, has always been a major hub for trade and travel. Initiated by the State Office for Monument Preservation in Baden-Württemberg, the "Wrecks and Deep Sea" project has employed a battery of modern technologies to create a comprehensive inventory of the lake's submerged cultural heritage.

Using high-resolution bathymetric data to identify anomalies on the lakebed, researchers then deployed side-scan sonar, ROVs, and divers to investigate potential targets. The results have been astonishing, with 31 previously unknown shipwrecks being identified.

Among the most significant finds are the hulks of two pioneering paddle steamers, believed to be theSD Baden--- and the SD Friedrichshafen II---. The Baden, launched in 1871 as the Kaiser Wilhelm, was the first saloon steamer on the lake and could carry up to 600 passengers. After a long career, she was decommissioned in 1930 and eventually sank. The Friedrichshafen II, commissioned in 1909, met a more violent end, being destroyed in a World War II air raid and subsequently scuttled in 1946. The discovery of these once-mighty vessels provides a direct link to both the golden age of steam navigation and the turmoil of the 20th century.

Perhaps the most remarkable discovery in Lake Constance, however, is a fully preserved wooden cargo sailing ship. Found with its mast and yardarm still intact, this vessel is a "rarity in underwater archaeology" and offers a unique insight into the shipbuilding techniques and sailing technology of a much earlier era of trade on the lake. The exceptional state of preservation, down to visible clamps on the bow and mooring pins, makes this wreck an invaluable reference for researchers. In another part of the lake, a field of at least 17 well-preserved wooden barrels, some still sealed, hints at a lost cargo, though the ship that carried them remains a mystery.

Lake Garda: From Venetian Warships to World War II Tragedies

Lake Garda, Italy's largest lake, has a history of maritime activity that stretches back centuries, and its depths hold the evidence of both ancient conflicts and modern warfare. One of the most fascinating discoveries is the wreck of a Venetian galley, which lies near the town of Lazise. Sunk in the early 16th century during the wars of the League of Cambrai, the vessel was part of a small Venetian fleet that was scuttled to prevent it from falling into enemy hands. The cold, dark, and muddy conditions at the bottom of the lake have preserved this Renaissance-era warship in excellent condition, offering a rare glimpse into the naval technology of the Venetian Republic.

In stark contrast to this ancient warship, another wreck in Lake Garda tells a story from the final days of the Second World War. In 2012, the wreck of an American DUKW, an amphibious military vehicle, was located at a depth of over 270 meters. The DUKW sank during a storm on the night of April 30, 1945, while transporting soldiers of the 10th Mountain Division. Tragically, 24 of the 25 soldiers on board lost their lives, just days before the war in Europe ended. The discovery of the wreck, sitting upright on the lakebed, brought a measure of closure to a long-unsolved mystery and serves as a poignant memorial to those who perished. The local community, in collaboration with the families of the soldiers, has since made plans to recover the vehicle and preserve it as a public monument.

Lake Geneva: The Belle Époque and a Tragic Swallow

Lake Geneva, shared by Switzerland and France, was a hub of steam navigation in the 19th and 20th centuries. The elegant paddle steamers of the CGN fleet are legendary, and while many still grace the lake's surface, others have found a permanent home at the bottom.

One of the most famous wrecks in Lake Geneva is the Hirondelle ("The Swallow"), a paddle steamer that sank in 1862. Her story is a dramatic one, involving a collision and a rapid descent into the depths. Today, she lies in deep water, a silent testament to the perils of 19th-century steam travel. The wreck was discovered by chance by divers in the 1960s and has since become a site of great interest for underwater archaeologists.

Another notable vessel is the Genève, the oldest paddle ship on the lake, built in 1896. While she did not sink in the traditional sense, her story is intertwined with a famous historical event. In 1898, Empress Elisabeth of Austria, the beloved "Sissi," was assassinated on the quay in Geneva just as she was about to board the Genève. After a long career, which included a conversion from steam to diesel power, the Genève was decommissioned in 1973. Saved from the scrapyard, she is now moored in Geneva and serves as a floating restaurant and social space, a living link to the lake's rich past.

Lake Lucerne and Lake Thun: Glimpses into Deeper History

While the larger lakes have yielded more spectacular industrial-era wrecks, the waters of Lake Lucerne and Lake Thun in central Switzerland are also revealing their secrets. In Lake Thun, the wreck of the steamer 'Bellevue' lies in the silt, 120 meters down. After its steam engine was removed in 1860, it was used as a tugboat until it sank in a storm in 1864.

More recently, archaeological work in both lakes has uncovered evidence of much older human activity. In Lake Lucerne, the construction of a pipeline led to the discovery of a submerged Bronze Age settlement, dating back to around 1000 BC. The find consisted of wooden piles from stilt houses, which had been preserved in the low-oxygen environment of the lakebed. This discovery pushed back the known history of settlement in the Lucerne area by some 2,000 years. Similarly, in Lake Thun, the remains of Bronze Age pile dwellings are being rescued by archaeologists from erosion caused by river currents and boat traffic. These prehistoric sites, while not "industrial" in the modern sense, demonstrate the long and continuous history of human reliance on these Alpine lakes, a history that the later industrial vessels were a part of.

The Archaeologist's Toolkit: Technology in the Depths

The documentation of sunken vessels in the challenging environment of Alpine lakes would be impossible without a sophisticated array of modern technologies. The great depths, cold temperatures, and often limited visibility of these lakes present a unique set of obstacles that require specialized tools and techniques.

Finding the Lost: Sonar and Bathymetry

The first step in any underwater archaeological project is to locate potential sites. Given the vastness of the Alpine lakes, this is a monumental task. The process often begins with the analysis of bathymetric data, which are detailed maps of the lakebed's topography. These maps can reveal anomalies—sudden changes in elevation or unusual shapes—that might indicate the presence of a shipwreck or other man-made structure.

Once a potential area of interest is identified, archaeologists employ side-scan sonar. This technology involves towing a "fish" behind a boat that emits fans of acoustic pulses, or "pings," down towards the lake floor. The returning echoes are used to create detailed, almost photorealistic images of the lakebed, revealing the outlines of any objects that lie there. This technique was instrumental in the recent project on Lake Constance, allowing researchers to sift through over 250 identified anomalies to pinpoint the 31 actual shipwrecks. For even more detailed subsurface mapping, other geophysical techniques like ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and seismic reflection profiling can be used to see what lies beneath the sediment.

Eyes in the Deep: Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs)

Many of the wrecks in the Alpine lakes lie at depths that are beyond the safe reach of human divers. Lake Constance, for example, reaches depths of over 800 feet (about 250 meters), and Lake Lucerne is even deeper. This is where Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) become essential. These unoccupied underwater robots, tethered to a surface vessel, are equipped with high-definition cameras, powerful lights, and manipulator arms.

Piloted by operators on the boat who watch the video feed in real-time, ROVs can be sent down to investigate sonar targets and provide the first visual confirmation of a wreck. They can survey the site in detail, recording video footage and taking high-resolution still photographs. This technology allows archaeologists to "visit" these deep-water sites safely and cost-effectively, gathering crucial data without having to mount complex and dangerous diving operations. The documentation of the deep-water wrecks in Lake Constance, such as the paddle steamers and the intact cargo ship, was heavily reliant on the use of ROVs. However, the effectiveness of ROVs can be hampered by factors like dense algal blooms, which can severely reduce visibility.

Rebuilding in the Digital Realm: 3D Photogrammetry

One of the most transformative technologies in modern underwater archaeology is 3D photogrammetry. This technique involves taking hundreds, or even thousands, of overlapping digital photographs of a wreck from multiple angles. This can be done by divers or, more commonly in deep lakes, by cameras mounted on an ROV.

This massive dataset of images is then fed into powerful software that analyzes the photos, identifies common points, and triangulates their positions in three-dimensional space. The result is a stunningly detailed and accurate 3D model of the shipwreck and its surrounding environment. These models are not just visually impressive; they are precise scientific instruments. Archaeologists can take measurements directly from the model, study the construction of the vessel, and analyze the distribution of artifacts on the site, all from the comfort of their lab.

This technology has several key advantages. It minimizes the time spent in the water, which is a major consideration in the cold and deep conditions of Alpine lakes. It creates a permanent, non-invasive record of the site "as is," which is crucial as these wrecks can be fragile and subject to degradation. And importantly, these 3D models can be used for public outreach, allowing anyone with a computer to take a virtual dive on a wreck that is physically inaccessible, bringing this hidden heritage to a global audience. The process is so advanced that it is now possible to create interactive 3D tours of wreck sites, with additional information and videos embedded within the model.

Guardians of the Depths: Preservation and Legal Frameworks

The discovery of a rich industrial heritage at the bottom of the Alpine lakes has brought with it a host of complex questions regarding preservation, ownership, and management. These wrecks are non-renewable cultural resources, and protecting them for future generations is a major priority for the archaeologists and authorities involved.

The Perfect Time Capsule: Preservation in Freshwater

One of the most remarkable aspects of the sunken vessels in the Alpine lakes is their extraordinary state of preservation. The unique conditions of these deep, cold freshwater environments create a near-perfect time capsule. Unlike in saltwater, where chemical corrosion and wood-boring organisms can rapidly destroy a wreck, the cold temperatures and low oxygen levels in the depths of the Alpine lakes inhibit the biological and chemical processes of decay.

This is why archaeologists in Lake Constance were able to find a wooden sailing vessel with its mast still standing and why the Venetian galley in Lake Garda has survived for five centuries in such good condition. However, these sites are not entirely immune to threats. The introduction of invasive species, such as the quagga mussel, which can colonize and obscure wreck sites, is a growing concern. Furthermore, changes in the lake environment, such as those brought about by climate change, could potentially alter the stable conditions that have preserved these wrecks for so long.

A fundamental principle of modern underwater archaeology, particularly in these environments, is in-situ preservation—that is, leaving the wrecks on the lakebed rather than raising them. The process of recovering a large, waterlogged wreck is not only incredibly expensive but also poses a massive conservation challenge. Once removed from the stable underwater environment, the waterlogged wood and metal can quickly deteriorate if not subjected to lengthy and complex chemical stabilization treatments. As Dr. Julia Goldhammer, the leader of the Lake Constance project, has emphasized, the focus is on documentation and long-term preservation, not salvage.

A Web of Laws: International and Cross-Border Agreements

The legal framework for protecting this underwater cultural heritage is complex, particularly as many of the largest Alpine lakes are trans-boundary waters, shared between multiple nations. This necessitates a high degree of international cooperation.

A key international treaty is the UNESCO 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. This convention establishes a legal framework for the protection of all traces of human existence that have been underwater for at least 100 years, promoting in-situ preservation and prohibiting the commercial exploitation of such sites. The ratification of this convention by Switzerland in 2019 was a significant step in strengthening the protection of the numerous prehistoric and industrial-era sites in its lakes.

For the trans-boundary lakes, a web of bilateral and multilateral agreements governs everything from water quality to navigation and fishing. On Lake Geneva, for example, a series of conventions between France and Switzerland addresses issues like pollution control and navigation. A specific agreement from 1980 governs fishing rights, which has implications for the protection of the lakebed from potentially damaging activities like trawling. While these agreements may not have been specifically designed for the protection of shipwrecks, they provide a foundation for cross-border cooperation in managing the lake's resources, including its cultural heritage.

Similarly, Lake Constance is managed through cooperation between Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, often through bodies like the International Lake Constance Conference (IBK). These bodies address issues of common concern, from environmental protection and spatial planning to the promotion of cultural heritage. The recent archaeological project on the lake is a prime example of this kind of cross-border collaboration in action, with researchers from different nations working together to document a shared heritage. The existence of these agreements is crucial for ensuring that the sunken vessels of the Alpine lakes are not caught in a jurisdictional limbo, but are instead treated as a shared European heritage that requires a unified approach to its protection and study.

The Human Element: Stories from the Age of Steam and Steel

Beyond the technical marvels of their construction and the economic data they provide, the sunken vessels of the Alpine lakes are, at their core, human stories. They are stories of the skilled engineers and shipwrights who built them, the captains and crews who piloted them through all weather, the passengers who traveled on them for business and pleasure, and in some cases, the tragic final moments of those who went down with their ships.

The era of steam navigation on the Alpine lakes, from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century, was a time of great change and activity. The paddle steamers were more than just a mode of transport; they were a part of the social fabric of the lakeside communities. They carried mail, supplies, and people, connecting the often-isolated villages along the shore. For many, a trip on one of the grand saloon steamers was a major event, an experience of modern luxury and speed.

We can catch glimpses of this life through historical records and personal accounts. In a letter written on April 10, 1912, from aboard the Titanic, passenger Juliette Laroche described the scene in the reading room: "an orchestra is playing next to me: one violin, two cellos, and one piano." It is easy to imagine similar scenes of elegance and leisure playing out on the great steamers of Lake Geneva or Lake Constance, which were designed to cater to a wealthy tourist clientele.

The work of the crews, however, was far from leisurely. Captaining one of these large vessels required immense skill and a deep, intuitive knowledge of the lake's often-treacherous conditions. As Captain Olivier Chenaux of the Lake Geneva General Navigation Company (CGN) explains, navigating the lake is about more than just charts and instruments; "you have to feel how the boat reacts, how it moves, it's instinctive." This sentiment is echoed by his predecessor, Aldo Heymoz, who emphasized the importance of listening and learning from everyone on board. These captains were responsible for the lives of hundreds of passengers and valuable cargo, a responsibility that weighed heavily.

Tragically, not all voyages ended safely at the dock. The historical accounts of sinkings, while often sparse on details, speak to the power of the Alpine storms and the fragility of these man-made machines in the face of nature. The collision of the Genève and the Rhône on Lake Geneva in 1928, which resulted in the death of a passenger, was a stark reminder of the dangers of lake travel. The sinking of the DUKW in Lake Garda in 1945, with the loss of 24 young soldiers, is a story of a wartime tragedy that lay hidden for nearly 70 years. Each of these wrecks is a memorial, a site of human loss that commands respect and solemnity.

The industrial barges and cargo vessels that were the workhorses of the lakes have their own human stories, though they are often harder to uncover. The men who worked on these vessels, transporting stone, timber, and other bulk goods, were engaged in hard, physical labor. Their lives were tied to the rhythms of the lake and the demands of the industries they served. While their stories are not often recorded in the grand histories of the region, the discovery and documentation of their vessels—the tools of their trade—give a voice to these forgotten workers of the Alpine industrial age. The remarkably preserved cargo ship in Lake Constance, with its simple, functional design, speaks volumes about the pragmatic and hardworking world of lake-based commerce, a world away from the gilded luxury of the passenger steamers.

As archaeologists continue to study these wrecks, they are not just documenting wood and steel; they are piecing together the lives of the people who inhabited this now-submerged world. Every artifact, from a broken piece of ceramic to a well-worn tool, is a fragment of a human story, waiting to be told.

The Future of the Past: A New Frontier in European Heritage

The exploration of the sunken industrial heritage of the Alpine lakes is a field still in its infancy, yet it has already yielded spectacular results and fundamentally altered our understanding of the region's history. The projects on Lake Constance and other Alpine lakes have demonstrated that these cold, deep waters are a vast and incredibly well-preserved museum of our industrial past, a museum whose collection is only now beginning to be cataloged.

The continued development of underwater technologies will undoubtedly open up new possibilities for exploration and documentation. More advanced ROVs, more sensitive sonar systems, and increasingly sophisticated 3D modeling techniques will allow archaeologists to survey larger areas with greater accuracy and to extract ever more information from the wrecks they discover. The ability to create photorealistic, interactive digital models means that this heritage can be shared with a global audience, allowing for virtual tourism and research that would have been unimaginable just a few decades ago.

However, this burgeoning field also faces significant challenges. The threats of invasive species, the potential impacts of climate change, and the ongoing pressures of tourism and development on the lakeshores all pose risks to the long-term preservation of these submerged sites. The need for robust legal frameworks and continued international cooperation between the nations that share these lakes will be paramount in ensuring that this heritage is protected.

The work of industrial archaeologists in the Alps is more than just an academic pursuit; it is an act of recovery and remembrance. It brings back into the light a vital chapter of European history that was thought to be lost. The stories of the steamships that united communities, the barges that fueled economies, and the people who lived and worked on these "liquid highways" are an essential part of the modern European identity. These sunken vessels are not just relics of a bygone era; they are a reminder of the ingenuity, the industry, and the deep connection to the natural world that has shaped the heart of the continent. As the exploration of these Alpine depths continues, we can be sure that many more secrets, and many more stories, are still waiting to be discovered.

Reference:

- https://www.ancientbeat.com/p/ancient-beat-163-domestication-the

- https://archaeology.org/news/2025/08/20/sunken-vessels-in-alpine-lake-documented/

- https://greekreporter.com/2025/08/15/lake-constance-shipwrecks-underwater-archaeology/

- https://dan.org/alert-diver/article/bringing-shipwrecks-to-life/

- https://opil.ouplaw.com/display/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e1311?d=%2F10.1093%2Flaw%3Aepil%2F9780199231690%2Flaw-9780199231690-e1311&p=emailAc3.Ol%2FwqNyiA

- https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/bi215408.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paddle_steamer_Gen%C3%A8ve

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224556937_Underwater_3D_mapping_and_pose_estimation_for_ROV_operations

- https://lettresdubrassus.blancpain.com/en/issue-13/steamers

- https://archive.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/LAKES%20Annex2c_Regional_report%20Constance.pdf

- https://opentug.com/blog/the-history-of-the-barge

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375088317_Late_Nineteenth-Century_Bulk_Trade_and_Barges_An_Historical_Overview_and_the_Likely_Context_of_Two_Deep-Water_Shipwrecks_in_the_Gulf_of_Mexico

- https://www.mdpi.com/2571-9408/6/1/21

- https://2001convention-uch.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/CMAS_Protection-of-underwater-cultural-heritage-27.3.24.pdf

- https://news.artnet.com/art-world/lake-constance-31-shipwrecks-2677596

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6Y2I4rm3sA

- https://3deepmedia.com/3d-shipwreck-modelling-visualisations/

- https://www.sia-web.org/

- http://www.worldlii.org/int/other/treaties/UNTSer/1978/68.pdf

- https://industrial-archaeology.org/

- http://www.paddlesteamers.info/LakeGenevaHistorical.htm

- https://iwlearn.net/documents/legal-frameworks/franco-swiss-genevese-aquifer

- https://www.greatlakesvesselhistory.com/

- https://industrial-archaeology.org/aia-awards/archaeological-report-award/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Constance_train_ferries

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387468930_Monitoring_Aquatic_Debris_in_a_Water_Environment_Using_a_Remotely_Operated_Vehicle_ROV_A_Comparative_Study_with_Implications_of_Algal_Detection_in_Lake_Como_Northern_Italy

- https://dspace.lib.cranfield.ac.uk/bitstreams/7df3b289-1581-49fb-9f91-08cdb301707c/download

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330505742_Encyclopedia_entry_Historical_Shipwrecks_Archaeometry_of

- https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/edu/materials/rov-challenges-exploration-notes.pdf

- https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3298/12/1/3

- https://glsps.clubexpress.com/content.aspx?page_id=22&club_id=625896&module_id=383413

- https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/bi-17479E.pdf

- https://www.bodenseekonferenz.org/bausteine.net/f/9631/2023-06-29-IBK-PositionspapierEU-endgEN.pdf?fd=0

- https://www.reddit.com/r/RMS_Titanic/comments/nrn7l9/letter_written_by_2nd_class_passenger_juliette/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376363204_Shipwreck_archaeology_in_the_past_10_years