On a frigid Wednesday morning, January 14, 2026, the recycled air of the excavation shelter over Pit No. 2 of the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum grew heavy with a distinct, electrified silence. For over five decades, since the peasant farmers of Lintong first struck the clay head of a warrior in 1974, the Terracotta Army has spoken to the world in the language of motion. The infantry marches; the archers kneel in preparation; the cavalry stands ready to mount. It is an army frozen in the nanosecond before the charge.

But the discovery announced today by the Emperor Qinshihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum changes that conversation.

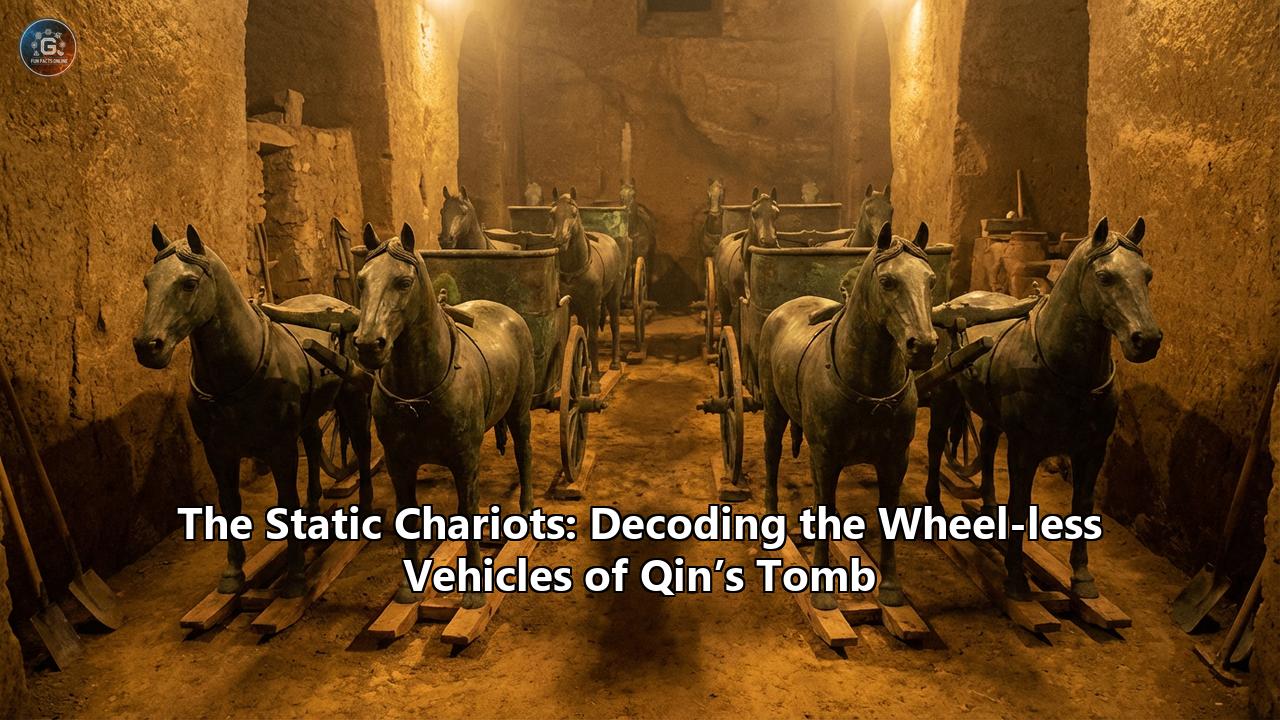

In the newly excavated eastern section of Passage 9, deep within the complex military formation of Pit 2, archaeologists have unearthed two wooden chariots that defy the logic of the entire necropolis. They are large, intricate, and laden with the tell-tale bronze fittings of high status. They are hitched to terracotta horses that strain against their harnesses. Yet, they are fundamentally different from the 140 other chariots found in the pits to date.

They have no wheels.

These are not vehicles that have lost their wheels to the decay of millennia, nor are they the victims of ancient looting. The soil strata tell a forensic truth: these chariots were deliberately, methodically buried without their primary means of movement. They were placed on the earth not as vehicles of transport, but as monuments of stasis. They are the "Static Chariots" of Qin, an anomaly that has sent ripples through the sinological community, challenging our understanding of the First Emperor’s vision of the afterlife.

This article delves into the heart of this new mystery, exploring the anatomy of these wheel-less wonders, the strategic genius of Pit 2, and the profound theological implications of a vehicle designed to never move.

Section I: The Anatomy of Stillness

To understand the magnitude of this discovery, one must first appreciate the engineering marvel that was the Qin chariot. The standard war chariot of the Qin Dynasty was a triumph of standardization and lethal efficiency. Typically drawn by four horses, it featured a single draught pole, a rectangular carriage box (about 1.5 meters wide), and two massive wooden wheels, each boasting 30 spokes—a number symbolizing the days of the lunar month.

When archaeologists excavate these wooden behemoths, the wood itself has long since disintegrated. What remains is a "soil ghost"—a perfect negative impression left in the packed earth, often preserved by the fine-grained loess soil of Shaanxi. By pouring plaster or specialized binding agents into these hollows, researchers can recover the exact dimensions of the spokes, the felloes (rims), and the hubs.

The Forensic Evidence

In the case of the newly discovered Static Chariots, the "soil ghost" told a different story.

Project leader Zhu Sihong and his team found the clear impressions of the draught poles. They found the rectangular carriage boxes, preserved with enough fidelity to show the texture of the wood grain and the lacquer that once coated them. They found the bronze wei (linchpins) and yi (handrails), gleaming green with 2,000 years of oxidation.

But where the great wheels should have been—flanking the carriage box, supporting the axle—there was only undisturbed, compacted earth. The axles themselves were present, protruding from the carriage body, but they ended abruptly. There were no hubs. No spokes. No rims.

Furthermore, the carriage boxes were not tilted or slumped as they would be if the wheels had been removed haphazardly or stolen. They sat perfectly level, supported by wooden blocking that had also left its faint trace in the soil. This indicates a careful, engineered placement. These vehicles were "docked" in the afterlife, raised on plinths or resting on their chassis, intended to remain exactly where they were placed for eternity.

The Bronze Clues

The layout of the artifacts around these chariots provides further clues. Unlike the war chariots in Pit 1, which are often surrounded by scattered weaponry suggesting the chaos of battle readiness, the Static Chariots of Pit 2 are surrounded by ceremonial artifacts.

The bronze components found—over 15 pieces of intricate horse and chariot gear—are of a higher grade than those found on common infantry chariots. Some fittings are inlaid with gold and silver, a technique usually reserved for the Emperor’s personal vehicles or those of the highest-ranking generals. The horses, too, show subtle differences; their terracotta bodies are slightly more robust, their grooming more meticulous, suggesting the stable of the imperial household rather than the cavalry of the line.

Section II: Pit 2 — The Tactical Labyrinth

To decode the function of the Static Chariots, we must look at their geography. Pit 2 is widely considered the "special forces" unit of the Terracotta Army. While Pit 1 is the massive infantry square—the sledgehammer of the Qin army—Pit 2 is the scalpel.

Shaped like a carpenter’s square or an "L," Pit 2 covers 6,000 square meters and contains a complex, mixed-arms formation. It is divided into four distinct units:

- The Archer Array: A projecting square of kneeling and standing crossbowmen, the vanguard designed to rain death from a distance.

- The Cavalry Array: A mobile force of horses and riders, the rapid-response team.

- The Chariot Phalanx: A dense block of 64 chariots, the heavy armor of the ancient world.

- The Mixed Unit: A sophisticated combination of infantry, chariots, and cavalry.

The Static Chariots were found in Passage 9, located in the mixed unit section, near the "joint" of the L-shape. In ancient Chinese military strategy, the joint of a formation is its most critical point—the hinge upon which the army swings. It is the command and control node.

The Stationary Command Post

The location strongly supports the theory that these wheel-less vehicles served as Command Chariots (zhihui che). In the chaos of a battlefield, the commander needed a stable platform from which to observe the field, issue orders via flags and drums, and remain visible to his troops.

However, command chariots in the field still needed wheels to advance or retreat. The fact that these specific command vehicles were buried without wheels suggests a shift from "field command" to "eternal command." In the context of the tomb, the battle has already been won, or perhaps the nature of the defense is static. The commander in Pit 2 does not need to maneuver; he needs to hold the line forever. The removal of the wheels signifies an absolute refusal to retreat. It is a physical manifestation of the order: "Stand your ground."

Section III: The Chariot in the Chinese Cosmos

The wheel is not just a mechanical invention in Chinese culture; it is a cosmological symbol. The round canopy of the chariot represents Heaven; the square carriage box represents Earth. The chariot is a microcosm of the universe, moving through space and time.

The Ritual of the Broken Vehicle

The burial of wheel-less vehicles is rare, but not entirely unprecedented in the broader context of ancient Chinese mortuary rites. In the Shang and Zhou dynasties (preceding the Qin), "killing" grave goods was a common practice. Bronze vessels were sometimes smashed, and weapons bent, before being placed in the tomb. This ritual destruction, or po, was believed to release the spirit of the object, allowing it to function in the shadow world (yinjian).

Perhaps the removal of the wheels was a form of ritual "killing" for the chariot. A chariot that cannot roll in the mortal world is perhaps freed to fly in the spiritual one.

The "Cloud Chariot" Theory

Some sinologists speculate that the Static Chariots align with the Taoist and mythological concepts of the "Cloud Chariot" (yunche). In the mythology of the Warring States period, immortals and deities traveled in vehicles that did not require roads. They rode on clouds, wind, or dragons.

Qin Shi Huang was obsessed with immortality. He sent Xu Fu to the eastern seas to find the Elixir of Life; he consumed mercury in hopes of transmuting his flesh. It is plausible that these wheel-less chariots were intended not for the terrestrial roads of the Qin Empire, but for the celestial highways of the heavens. By removing the terrestrial wheels, the vehicle was symbolically converted into a palanquin or a celestial barge, ready to be lifted by the spirits rather than pulled by horses across the dirt.

Section IV: The Psychology of the First Emperor

The discovery of the Static Chariots offers a terrifying glimpse into the mind of Qin Shi Huang. This was a man who standardized the width of chariot axles across his empire to ensure that all vehicles could travel in the same ruts. He was a ruler obsessed with mobility, inspection, and the unification of space.

Why, then, would he bury immobile vehicles?

Paranoia and Defense

The Emperor survived multiple assassination attempts, including a famous incident where a musician swung a lead-weighted lute at him, and another where his carriage was ambushed by a strongman hurling a massive iron hammer (which hit the wrong carriage).

This trauma bred a deep paranoia. In his later years, he moved through his palaces via secret underground tunnels to avoid detection. The Static Chariots in Pit 2 might represent the ultimate defensive counter-measure. A wheeled chariot can be hijacked; it can be driven away. A wheel-less chariot is a bunker. It is a fortress. By burying his spectral commanders in immovable vehicles, Qin Shi Huang was ensuring that his underground guard could never abandon their posts, nor could his own escape vehicles be used against him by mutinous spirit-soldiers.

The Weight of Eternity

The absence of wheels also speaks to the permanence of death. Wheels imply transit; they imply a journey with a beginning and an end. The Qin Mausoleum was not a waystation; it was the final destination. The Emperor built a replica of the universe underground, complete with mercury rivers and constellation ceilings. In such a perfect, self-contained world, travel becomes unnecessary. The Static Chariots are symbols of arrival. The conquest is over. The Emperor is home.

Section V: A Technical Marvel of Conservation

The excavation of the Static Chariots in 2026 represents a triumph of modern archaeological technology. In the 1970s and 80s, excavators often struggled with the fragile "soil ghosts" of wood. Today, the team at the Emperor Qinshihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum employs multi-spectral imaging and 3D laser scanning before a single grain of dirt is moved.

For the Static Chariots, this technology allowed the team to detect the absence of the wheels before they fully exposed the chassis. This prevented the accidental destruction of the wooden blocking that supported the carriage boxes.

The conservationists are now facing a unique challenge: how to display a "negative space." Plans are underway to create holographic projections that overlay the excavated pits, showing the chariots as they would have looked—floating just above the ground on their supports, the "phantom wheels" highlighted to emphasize their deliberate absence.

Conclusion: The Empire of Shadows

The discovery of the Static Chariots in Pit 2 is a humbling reminder that after 50 years, the Terracotta Army still has secrets to tell. We have long looked at the faces of the warriors, admiring their individuality. Now, we must look at their machines and the empty spaces where function used to be.

These wheel-less vehicles challenge the simplistic view of the Terracotta Army as a mere replica of a living army. They reveal it to be something far more complex: a ritual machine, designed with a logic that blends military strategy with theological necessity.

The Static Chariots stand as silent sentinels to a paradox: the Emperor who built the roads to unify China chose to face eternity in a vehicle that could never move. In the silence of Pit 2, they offer a final, motionless salute to a ruler who believed that his power was so absolute, it no longer needed wheels to turn the world.