Introduction: The Golden Tiger and the Masked Ancestors

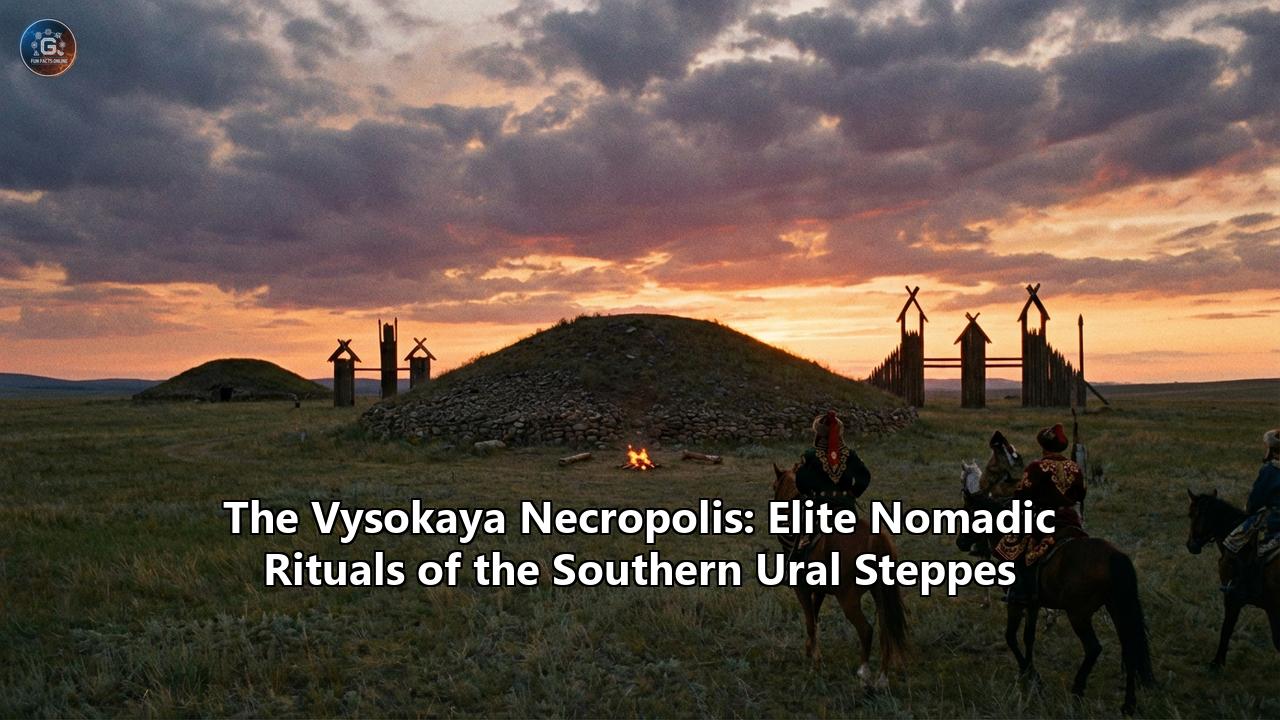

In the vast, wind-swept expanse of the Southern Ural Steppes, where the horizon seems to stretch into infinity, the earth has once again whispered secrets of a forgotten empire of horse lords. For centuries, the burial mounds—known as kurgans—have dotted this landscape like sleeping giants, marking the final resting places of the nomadic elite who once ruled the Eurasian bridge between East and West. They were the masters of the saddle, the inventors of the armored cavalry charge, and the artisans of gold. We know them as the Early Sarmatians.

In the summer of 2025, a team from the Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, led by researchers Sergey Sirotin and D.S. Bogachuk, unearthed a discovery that has fundamentally rewritten our understanding of these ancient people. Excavating at the immense Vysokaya Mogila-Studenikin Mar necropolis in the Orenburg region, they did not find just another grave. Instead, hidden in the "inter-mound" space—the sacred earth between the monuments—they discovered a spectacular sacrificial complex.

It was a treasure trove of ritual intent: rare bronze mask pendants with stylized human faces, a gold plaque depicting the predatory grace of a tiger, silver-overlaid wooden bowls, and complete sets of elite horse tack. These were not mere grave goods buried with the dead; they were offerings left by the living, evidence of complex, recurring rituals designed to honor ancestors and maintain the cosmic order.

This article delves deep into the world of the Vysokaya Necropolis, exploring the 2025 discovery in unprecedented detail. We will journey back to the 4th century BC to understand the lives, beliefs, and artistic genius of the nomadic elites who transformed the Southern Urals into a center of power, trade, and spiritual mystery.

Part I: The Landscape of the Dead

To understand the significance of the Vysokaya discovery, one must first understand the stage upon which this drama played out. The Southern Ural region, specifically the Ural-Ilek interfluve, is a geographic pivot point. To the north lie the forests; to the south, the arid deserts of Central Asia; to the west, the Volga and the path to Europe; and to the east, the boundless steppes leading to the Altai and Mongolia.

The Necropolis of Giants

The Vysokaya Mogila-Studenikin Mar necropolis is not a single site but a sprawling "city of the dead" extending for over six kilometers along a latitudinal axis. It comprises five distinct groups of kurgans, totaling nearly 14 large mounds and numerous smaller ones. These are not subtle features. The largest structure, Kurgan 1, is a monumental feat of prehistoric engineering, measuring an astounding 140 meters in diameter and rising over 7 meters in height—even after thousands of years of erosion.

In the ancient world, such a monument would have been visible for miles, a terraformed statement of power. It signaled to any traveler or rival clan: “Here lie the kings of the steppe. Here is the center of the world.”

The Stratigraphy of History

While the headline-grabbing discoveries date to the Early Sarmatian period (4th–early 3rd century BC), the site itself sits atop a deep well of history. The Southern Urals have been a crucible of nomadic culture for millennia, from the Bronze Age charioteers of the Sintashta culture to the later waves of migration that formed the Scythian and Sarmatian confederations.

The location of Vysokaya Mogila was chosen carefully. In the nomadic worldview, the landscape was alive. Kurgans were often placed on high ground or along river terraces, serving as celestial markers and territorial claims. They were the anchors for a people who were constantly on the move. The return to these necropolises for seasonal rituals provided a sense of permanence and continuity in a life defined by the rhythm of the seasons and the migration of herds.

Part II: The 2025 Discovery – The Sacrificial Pit

For decades, archaeologists focused their efforts on the kurgans themselves, tunneling into the center to find the burial chambers. However, the 2025 excavation season brought a paradigm shift. The team expanded their search to the inter-mound space—the flat ground between the giant tumuli. It was here, to the west and east of the massive Kurgan 1 and near Mound 19, that the soil yielded its surprises.

The Ritual Complex

Initially, the team found scattered fragments in the ploughed soil: iron bits, bronze cheekpieces, and broken pottery. These were the crumbs of a larger feast. Digging deeper, they uncovered a shallow, circular pit that had miraculously escaped the destruction of modern agriculture and ancient looters.

Inside lay a dense, deliberately arranged concentration of artifacts. This was not a trash pit, nor a hidden cache. It was a sacrificial deposit. The objects had been placed there with reverence, likely accompanied by prayers, chants, and the burning of incense.

The inventory of the pit is staggering in its richness and variety:

- Over 100 bronze artifacts, including elaborate horse harness decorations.

- A gold plaque depicting a tiger, a masterpiece of the "Animal Style."

- Bronze mask pendants, a find so rare it has few parallels in the region.

- Silver-mounted wooden vessels, indicators of high-status feasting.

- Boar jawbones, the remnants of a blood sacrifice.

- Over 500 bronze beads, likely sewn onto a ritual cloth or garment that has since disintegrated.

Post-Funerary Rites

The location of this pit is crucial. It was not inside a grave. This suggests that the rituals performed here happened after the funeral, perhaps years or even decades later. We are looking at evidence of a memorial cult. The nomadic elites did not just bury their dead and move on; they returned. They held feasts, sacrificed animals, and deposited precious heirlooms to honor the spirits of the ancestors buried in the great Kurgan 1. This was a way to "recharge" the spiritual power of the site and reaffirm the legitimacy of the ruling clan.

Part III: The Artifacts – A Window into the Elite Mind

The objects found at Vysokaya Mogila are not merely decorative; they are texts written in metal and bone, telling us about the beliefs, trade connections, and social hierarchy of the Sarmatians.

1. The Golden Tiger: Apex Predator of the Steppe

The star of the collection is the gold plaque featuring the head and foreleg of a tiger. In the "Animal Style" art of the steppes, animals were never chosen at random. They represented specific powers, deities, or clan totems.

The tiger is a complex symbol. While tigers existed in Central Asia (the Caspian tiger), they were less common in the Urals than wolves or bears. This rarity made the tiger an exotic symbol of royal power and ferocity.

- The "Animal Style": The plaque is crafted in the classic steppe tradition—fluid lines, exaggerated features, and a dynamic pose that captures the animal's latent energy. The tiger is not sleeping; it is hunting.

- Symbolism: For a warrior aristocracy, the tiger embodied the ultimate martial virtues: stealth, explosive power, and dominance. Wearing or offering such an item was a way to claim these attributes for oneself or the ancestor.

2. The Bronze Masks: The Face of the Spirits

Perhaps the most mysterious finds are the bronze pendants shaped like human faces. These "masks" are small but psychologically imposing.

- Unprecedented Rarity: Anthropomorphic (human-shaped) art is relatively rare in Sarmatian culture compared to animal imagery. Finding a concentration of these masks in a ritual pit is a sensation.

- Shamanic Connections: In many Siberian and Central Asian traditions, masks are the tools of the shaman. They allow the wearer to assume a different identity, to travel between the worlds of the living and the dead. These small bronze masks may have been sewn onto a shaman's costume or hung on a sacred tree or altar during the ritual.

- Ancestral Visages: Alternatively, they could represent the ancestors themselves—stylized portraits of the "Old Ones" watching over the tribe. Their presence in the offering pit suggests a direct communication with the spirit world.

3. The Silver and Wood: The Ritual Feast

The discovery of a wooden bowl with silver overlays is a testament to the importance of feasting. In nomadic society, the "feast" was a political and religious institution. It was where alliances were forged, disputes settled, and gods honored.

- The Vessel: Wood was the material of the steppe (light, durable), but wrapping it in silver elevated it to the divine. The silver fittings were likely decorated with zoomorphic motifs, turning the bowl into a microcosm of the universe.

- The Drink: These bowls were likely used for consuming koumiss (fermented mare's milk) or wine imported from the south. Sharing a cup was a sacred bond. The act of breaking a ceramic vessel (fragments of which were found) and burying a precious bowl suggests a ritual of "killing" the object to send it to the afterlife.

4. The Horse Gear: The Wings of the Nomad

The sheer volume of horse tack—complete bridle sets, iron bits, psalia (cheekpieces), and phalerae (decorative discs)—confirms the centrality of the horse.

- Hooked Terminals & Openwork: The team found browbands with "hooked terminals" and openwork plaques featuring swastikas (a solar symbol in antiquity), birds, and mythical beasts.

- The Horse as Psychopomp: In Indo-Iranian mythology, the horse is the carrier of the soul. It guides the deceased across the threshold of death. By burying elite tack, the living were ensuring the ancestor had the proper mount to ride in the celestial pastures.

Part IV: The People – The Early Sarmatians

Who were the people who left these treasures? The artifacts link Vysokaya Mogila to the Prokhorovka culture (Early Sarmatian) and the famous Filippovka cultural circle.

The Lords of the Steppe

The 4th century BC was a "Golden Age" for the nomads of the Southern Urals. They controlled the trade routes that connected the fur-trapping forests of the north with the silk roads of the east and the Greek colonies of the Black Sea.

- Social Stratification: The size of Kurgan 1 proves that this was a highly stratified society. This was not a simple tribal democracy. There were kings, queens, and a warrior aristocracy that could command the labor of thousands to build these earthen pyramids.

- The Filippovka Connection: The famous Filippovka I kurgans, excavated nearby, yielded the massive "Golden Deer" statues. Vysokaya Mogila is part of this same cultural phenomenon—a network of royal clans who shared a common artistic and religious language.

The Amazons of the Urals

No discussion of Sarmatians is complete without mentioning their women. Archaeological evidence from the region (such as the Pokrovka mounds) has shown that Sarmatian women were often buried with weapons—swords, bows, and armor.

- Warrior Priestesses: The presence of "feminine" jewelry (beads, mirrors) alongside "masculine" ritual gear and weapons in Sarmatian graves suggests that women held high status, potentially serving as war leaders or priestesses. It is entirely possible that the rituals at the Vysokaya sacrificial pit were conducted by, or in honor of, powerful women of the clan.

A Culture of War and Gold

The Sarmatians were the armored tanks of the ancient world. Unlike the lighter Scythian archers, Sarmatian nobles developed the cataphract style of warfare—heavy armor for both man and horse, and the use of the contus, a long lance. The wealth generated by mercenary work and tribute allowed them to commission the exquisite gold and bronze work found at Vysokaya.

Part V: The Ritual Landscape – How the Complex Worked

The findings at Vysokaya Mogila allow us to reconstruct the "theater" of the ritual that took place 2,400 years ago.

Step 1: The GatheringThe clan would gather at the necropolis, likely at a specific time of year (spring or autumn equinox). They would set up their felt yurts in the shadow of the great Kurgan 1, creating a temporary city of the living among the dead.

Step 2: The SacrificeA wild boar—a symbol of ferocity and fertility—was hunted or brought to the site. Its slaughter was the central act. The jawbones found in the pit are the enduring evidence of this blood offering. The meat was likely cooked and eaten in a communal meal, sharing the essence of the animal with the ancestors.

Step 3: The DepositionIn a shallow pit dug into the virgin soil (symbolizing an opening to the underworld), the priest or clan leader would place the offerings.

- The bridles were laid out, perhaps symbolizing a spectral team of horses.

- The gold tiger and bronze masks were carefully arranged, possibly oriented towards the cardinal points or the sun.

- The wooden bowl was placed among them, filled with a final offering of milk or wine.

The pit was covered, but not marked with a mound. It was a secret gift to the earth. The "inter-mound" space thus became a charged field of invisible offerings, transforming the entire area between the kurgans into holy ground.

Part VI: The Wider World – Trade and Connection

The Vysokaya discovery proves that the Southern Urals were not an isolated backwater. They were a hub of globalization in the Iron Age.

- Southern Connections: The technique of the gold work and the silver vessels points to influence from the Achaemenid Empire (Persia) and Central Asia.

- Western Connections: The "openwork" bronze plaques have parallels in the North Caucasus, the Don Basin, and even the Scythian lands of the Northern Black Sea.

- The Fur Route: The nomadic elites likely traded furs, slaves, and horses to the Greeks and Persians in exchange for wine, oil, and the precious metals they used to create their art.

The "tiger" motif itself is a traveler. While tigers roamed the reeds of Central Asia, the artistic rendering often borrows from the "griffin" motifs of the Near East and the "coiled animal" motifs of Siberia. The Vysokaya tiger is a synthesis of these worlds.

Conclusion: The Echoes of Vysokaya

The discovery of the sacrificial complex at Vysokaya Mogila-Studenikin Mar is one of the most significant archaeological events of the decade for steppe studies. It moves the conversation beyond "grave robbing" (finding gold in burials) to "reconstructing religion" (understanding the rituals in the spaces between).

It reveals a society that was deeply spiritual, artistically sophisticated, and fiercely proud. The Early Sarmatians of the Southern Urals were not just wandering barbarians; they were the architects of a complex civilization that honored its past while forging a network that spanned a continent.

As the winds continue to blow over the Orenburg steppe, smoothing the contours of the great Mound 1, we now know that the ground beneath the grass is thick with the memories of feasts, prayers, and the golden glint of the tiger—silent witnesses to the grandeur of the nomad kings.

Key Takeaways for the Enthusiast:

- Site: Vysokaya Mogila-Studenikin Mar (Orenburg Region, Russia).

- Period: Early Sarmatian (4th–3rd Century BC).

- Major Find (2025): Inter-mound sacrificial complex.

- Star Artifacts: Gold tiger plaque, bronze mask pendants, elite horse tack.

- Significance: Proves the existence of elaborate post-funerary memorial cults and extensive trade networks.

Reference:

- https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/eurasian-steppe-sacrificial-complex-00102351

- https://archaeologymag.com/2025/12/sacrificial-complex-unearthed-in-southern-urals/

- https://arkeonews.net/bronze-mask-pendants-tiger-motifs-and-elite-horse-gear-rare-4th-century-bc-ritual-complex-discovered-in-the-southern-urals/

- https://www.evrazstep.ru/index.php/aes/article/download/846/868/1017

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarmatians

- https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/severokavkazskie-donskie-i-podneprovskie-importy-v-uzdechnyh-naborah-iz-kurganov-nekropolya-vysokaya-mogila-studenikin-mar-v

- https://sanxingduiruins.com/bronze-masks/sanxingdui-bronze-masks-exploring-ancient-artifacts.htm

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381378027_DEPICTION_OF_WILD_BOAR_IN_SCYTHIAN_ART

- https://www.horsenation.com/2025/03/06/womens-history-month-scythia-and-sarmatia/

- https://www.zmescience.com/science/archaeology/sarmatian-warrior-tomb-18082015/

- https://ground.news/interest/archaeology

- https://greekreporter.com/2025/12/03/sacrificial-complex-ancient-necropolis-russia/