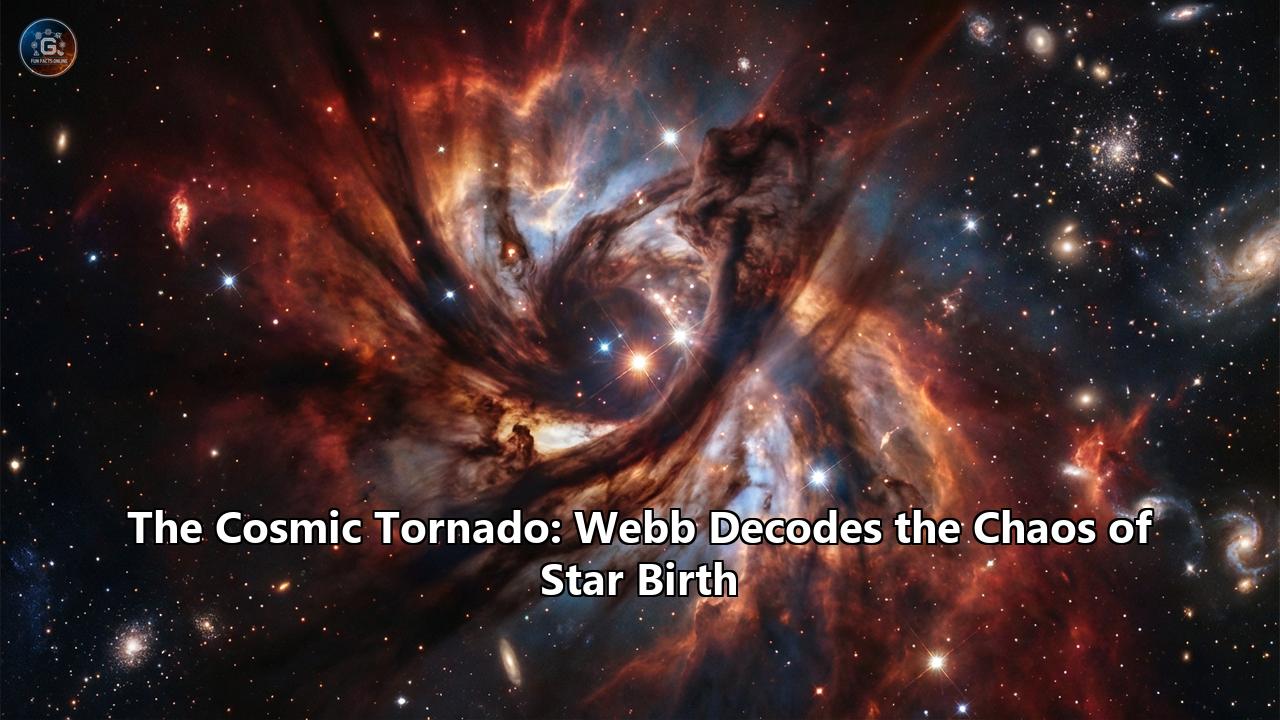

The universe, for all its silent majesty, is not a still painting. It is a roaring, turbulent ocean of creation, nowhere more violent than in the nurseries where stars are born. For decades, astronomers have peered into these dark clouds, catching glimpses of the chaos through the veil of dust. But with the advent of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the veil has not just been lifted; it has been shredded, revealing the violent, supersonic mechanics of stellar birth in terrifyingly beautiful detail. Among the most recent and spectacular of these revelations is a structure that has captured the imagination of the scientific community and the public alike: Herbig-Haro 49/50, now famously dubbed the "Cosmic Tornado."

This towering structure, a helical pillar of energized gas and dust, stands as a testament to the raw power unleashed when a star comes into existence. It is not merely a static sculpture but a snapshot of a supersonic collision, a record of the forces that shape the cosmos on both the grandest and most intimate scales. To understand the Cosmic Tornado is to understand our own origins, for this chaotic tempest is likely a mirror image of the environment that spawned our Sun and Solar System some 4.6 billion years ago.

The Theater of Darkness: The Chamaeleon I Molecular Cloud

To fully appreciate the drama of the Cosmic Tornado, one must first understand the stage upon which it plays. The object resides approximately 625 light-years away in the constellation Chamaeleon, deep within a vast complex known as the Chamaeleon I molecular cloud. To the naked eye, this region is a void—a patch of sky seemingly devoid of stars. But in the infrared eyes of Webb, it lights up as a bustling metropolis of stellar activity.

Molecular clouds are the coldest and densest parts of the interstellar medium. They are the womb of the galaxy, composed primarily of molecular hydrogen and helium, laced with a smattering of heavier elements and dust grains—microscopic flecks of carbon and silicates. These clouds are not uniform; they are turbulent, swirling reservoirs of matter where gravity is constantly fighting against internal pressure. When gravity wins, pockets of gas collapse inward, spinning faster and faster as they shrink, eventually igniting the nuclear fires of a new star.

It is within this darkened theater that the protostar responsible for the Cosmic Tornado resides. The star itself, likely a Class I protostar known as Cederblad 110 IRS4, is effectively invisible in optical light, shrouded by the very cocoon of material from which it is feeding. However, its presence is announced not by its light, but by its fury. As the star feeds, consuming gas from a swirling accretion disk, it suffers from a form of cosmic indigestion. Powerful magnetic fields, twisted by the rotation of the infalling gas, launch jets of ionized matter from the star’s poles. These jets scream into the surrounding cloud at hundreds of thousands of miles per hour, acting as snowplows that carve out cavities and crash into the stationary gas ahead. The Cosmic Tornado is the result of one such collision.

Deconstructing the Tornado: Herbig-Haro 49/50

The term "Herbig-Haro object" (HH object) refers to these specific patches of nebulosity associated with newborn stars. They are transient phenomena, lasting only a few thousand years—a blink of an eye in cosmic time. HH 49/50 is unique among them for its distinct, vertical, tornado-like appearance.

In the high-resolution near-infrared and mid-infrared images captured by JWST’s NIRCam and MIRI instruments, the "tornado" reveals its true nature. It is a series of bow shocks, similar to the waves created by the prow of a ship moving through water. The jet from the protostar pulses over time; it does not flow smoothly like water from a tap but rather "burps" in episodic ejections. Each pulse travels outward, eventually slamming into the slower material ejected previously or the surrounding interstellar medium.

The "ropey" or twisted texture of the tornado suggests that the jet is wandering or precessing. Imagine a spinning top that wobbles as it rotates; if that top were spewing a stream of paint, the pattern on the walls would be a spiral or helix. Similarly, the source star of the Cosmic Tornado is likely wobbling, or perhaps interacting with a binary companion, causing the jet to trace a corkscrew path through space. As this high-speed material collides with the cloud, it generates shockwaves that heat the gas to thousands of degrees. This superheated gas glows, not in visible light, but in the infrared wavelengths that JWST detects.

The colors in the Webb images are scientifically mapped to reveal the chemical composition of the tornado. The fiery oranges and reds typically represent molecular hydrogen (H2) and carbon monoxide (CO) that have been excited by the shocks. These molecules are the cooling agents of the universe; by radiating away the heat generated by the shock, they allow the gas to compress and cool, potentially seeding the formation of future stars or planets in the wake of the turbulence.

The Cosmic Photobomb: An Illusion of Alignment

Perhaps the most striking feature of the new JWST image of HH 49/50 is what sits atop the tornado. Perched perfectly at the summit of the chaotic funnel is a bright, fuzzy object that looks for all the world like the "eye" of the storm or perhaps a companion star being devoured.

For years, observing with less powerful telescopes like Spitzer, astronomers were puzzled by this object. Was it the protostar itself? Was it a massive clump of matter being ejected? Webb has solved the mystery, and the answer serves as a humbling reminder of the vastness of space.

The object is not part of the tornado at all. It is a distant spiral galaxy, located millions of light-years in the background. It is a cosmic coincidence of alignment—a "photobomb" on an intergalactic scale. The galaxy is seen face-on, its spiral arms clearly defined, with a blue central bulge of older stars and reddish knots of star formation in its arms.

This chance alignment provides more than just a pretty picture; it offers a sense of scale. The Cosmic Tornado, for all its immense size—stretching perhaps a light-year in length—is a local event, a microscopic splash in our own galactic backyard. The galaxy in the background is a city of billions of stars, reduced by distance to a mere bauble atop a pillar of dust. It contrasts the mature, ordered structure of an evolved galaxy with the raw, chaotic violence of a single star’s birth.

Decoding the Chaos: The Physics of Outflows

To understand why the Cosmic Tornado looks the way it does, we must delve into the magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) of star formation. Why do stars launch jets in the first place? The answer lies in the problem of angular momentum.

As a cloud of gas collapses to form a star, it begins to spin. This is the same principle as an ice skater pulling in their arms to spin faster. If this spin were unchecked, the centrifugal force would eventually tear the young star apart or prevent it from gathering more mass. The star needs a braking mechanism—a way to shed this excess rotational energy.

The jets are that brake. The protostar is surrounded by an accretion disk of infalling material. This disk is threaded with magnetic field lines. As the disk spins, these field lines get twisted and wound up like a spring. The tension in these magnetic fields becomes so great that it snaps, flinging material out along the rotation axis at supersonic speeds. This ejected material carries away the excess angular momentum, allowing the remaining gas in the disk to safely spiral inward and fall onto the star.

In HH 49/50, Webb has revealed the complexity of this process. The shocks seen in the tornado are not uniform. We see "knots" and "clumps" where the density of the jet varies. This tells us about the accretion history of the star. A bright knot might correspond to a period where the star gorged itself on a massive clump of dust, causing a violent ejection. A fainter gap might represent a period of relative quiet. In this way, the Cosmic Tornado is a historical record, a timeline of the star's feeding habits written in glowing gas.

A Tale of Three Outflows: HH 49/50, HH 211, and HH 797

The Cosmic Tornado does not stand alone. It is part of a "golden age" of protostellar imaging ushered in by JWST. To fully grasp the significance of HH 49/50, we must compare it to its "siblings"—other Herbig-Haro objects recently decoded by Webb, specifically HH 211 and HH 797.

HH 211: If HH 49/50 is a tornado, HH 211 is a supersonic lance. Located in the Perseus molecular cloud, HH 211 is one of the youngest and nearest protostellar outflows known. The Webb images of HH 211 revealed a textbook bipolar jet—two beams of matter shooting out in opposite directions from a central, hidden star. What made this observation revolutionary was the detection of slow-moving molecular shocks. Unlike the high-energy atomic shocks seen in older stars, HH 211 is dominated by molecules like carbon monoxide and silicon monoxide that have survived the violence of the jet. This suggests that in the very earliest stages of star birth (Class 0), the jets are composed of "pristine" molecular material plucked directly from the cloud, rather than processed atomic gas. The "wiggle" seen in the HH 211 jet also hinted at a binary companion, reinforcing the idea that binary stars are the rule, not the exception, in star formation. HH 797: Also in Perseus, HH 797 offers a different flavor of chaos. For years, ground-based observations showed a velocity gradient across the jet—one side was moving towards us, the other away. Astronomers thought this meant the jet was rotating. Webb, however, with its sharper vision, revealed that this was an illusion. HH 797 is not one jet, but two parallel jets flowing side-by-side. This means the source is not just a binary star, but a binary pair where both stars are launching their own independent jets. It is a chaotic dance of dual engines, creating a tangled mess of shocks that looks less like a tornado and more like a cosmic tangled wire.Comparing these to HH 49/50, we see the diversity of stellar birth. HH 49/50 lacks the perfect symmetry of HH 211, suggesting it is interacting with a messier, more inhomogeneous environment. Its "tornado" shape implies a strong precession, perhaps driven by a binary companion on a misaligned orbit. While HH 211 shows us the pristine "start" of the process, and HH 797 shows us the complexity of binary interaction, HH 49/50 shows us the interaction with the environment—the turbulence generated when a jet meets the resistance of the molecular cloud.

The Infrared Revolution: Why Webb?

Why are we only seeing this now? Hubble has imaged Herbig-Haro objects before, and they were spectacular. But Hubble operates primarily in visible and ultraviolet light. In the dense, dusty nurseries of star formation, visible light is blocked. It scatters off the dust grains, creating dark, opaque walls—the "Pillars of Creation" effect.

Webb operates in the infrared. Infrared light has longer wavelengths that can slip past dust grains without scattering. This allows Webb to look inside the clouds. But it’s not just about seeing through the dust; it’s about what the dust and gas are doing.

The instruments used to image the Cosmic Tornado—NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) and MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument)—are tuned to specific "colors" of infrared light that correspond to specific molecules.

- Molecular Hydrogen (H2): This is the dominant component of the jet. When shockwaves hit the cold hydrogen gas, they excite the molecules, causing them to vibrate and emit light at specific infrared wavelengths (e.g., 2.12 microns). Webb’s filters can isolate this light, allowing astronomers to map the exact structure of the shockwaves.

- Carbon Monoxide (CO) and Silicon Monoxide (SiO): These molecules trace the outflow itself. SiO, in particular, is a "shock tracer." It is usually locked up in dust grains (silicates), but powerful shocks shatter these grains, releasing the silicon into the gas phase where it forms SiO. Seeing bright SiO emission is a smoking gun for violent, high-speed collisions.

- Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs): Detected by MIRI, these complex organic molecules trace the boundaries of the cavity, showing where the jet is eroding the surrounding cloud.

By combining these different chemical "layers," astronomers can build a 3D model of the Cosmic Tornado, measuring the temperature, density, and speed of the gas at every point along the structure.

Solar Analogs: A Mirror to the Past

The study of HH 49/50 is not just an exercise in abstract astrophysics. It is a form of archaeology. Our Sun is a middle-aged star, 4.6 billion years old. Its birth records have long been erased. The gas from which it formed is gone, blown away or incorporated into the planets. The turbulence of its nursery has settled into the clockwork stability of the Solar System.

But once, the Sun was a Cederblad 110 IRS4. Once, the Solar System was a chaotic nebula, pierced by a bipolar jet. We know this because of the "scars" left in meteorites—calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions (CAIs) that show signs of having been flash-heated to extreme temperatures. For decades, the source of this heating was debated. Was it a nearby supernova? A fluctuation in the sun?

Observations of objects like the Cosmic Tornado suggest that these jets and their associated bow shocks could be the culprits. As the jet slams into the disk or the surrounding cloud, it creates zones of immense heat and turbulence. Dust grains caught in these "tornadoes" would be melted and re-condensed, forming the CAIs we find in meteorites today. Furthermore, the turbulence generated by these outflows stirs the pot, mixing elements and isotopes throughout the protoplanetary disk.

When we look at HH 49/50, we are watching a solar system being baked. We are seeing the mechanism that mixes the ingredients of life—carbon, oxygen, silicon—ensuring that they are distributed to the regions where planets will eventually form. The "chaos" of the tornado is actually a necessary mixing process, a cosmic blender that ensures the chemical richness of future worlds.

The Dynamics of Destruction and Creation

The interaction between the jet and the cloud is a double-edged sword. On one hand, the jet is destructive. It blasts away the envelope of gas, limiting the final mass of the star. If the jet is too powerful, it might strip the accretion disk entirely, halting the formation of planets. The "cavities" carved by the Cosmic Tornado represent material that will never become part of a star or planet; it is lost to the interstellar medium.

On the other hand, this destruction is creative. The shockwaves compress the surrounding gas. If a shockwave hits a dense clump of gas, it might compress it enough to trigger gravitational collapse. In this scenario, the death throes of one star's formation become the birth pangs of another. This is known as "triggered star formation." The Cosmic Tornado, as it whips through the Chamaeleon cloud, may be setting off a chain reaction, igniting a new generation of stars along its path.

This feedback loop is crucial for the evolution of galaxies. Without jets and outflows, star formation would be inefficient. The gas would simply sit there. The turbulence injected by things like HH 49/50 keeps the galaxy "alive," regulating the rate at which stars form and preventing the gas from collapsing all at once.

Future Horizons: The Movie in the Making

The image of the Cosmic Tornado is just a single frame in a movie that lasts thousands of years. But astronomy is changing. With the precision of JWST, we can hope to see changes on human timescales. By revisiting HH 49/50 in five or ten years, astronomers will be able to measure the "proper motion" of the knots. We will see them move against the background stars. We will see the shockwaves expand and fade.

This "time-domain astronomy" will allow us to measure the exact speed of the jet, the deceleration of the shocks, and the cooling rates of the gas. We will stop guessing at the physics and start measuring it directly.

Furthermore, future observations will focus on the source star itself. Using ALMA (the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) in conjunction with JWST, astronomers can pierce even deeper into the dust, imaging the accretion disk itself. We want to see the connection point—the "launch pad" where the magnetic fields rip the gas from the disk and fling it into the tornado. We want to understand the "battery" that powers this cosmic engine.

Conclusion: The beauty of Understanding

The Cosmic Tornado, HH 49/50, is a masterpiece of nature. Visually, it is stunning—a pillar of fire set against the cold velvet of space, crowned by a distant galaxy. But its true beauty lies in what it tells us. It decodes the chaos of our own origins. It reveals the invisible forces of magnetism and turbulence that sculpt the universe.

Webb has turned the lights on in the nursery. We are no longer stumbling in the dark, guessing at the shapes of the monsters in the room. We see them clearly now. We see the violence, the energy, and the intricate dance of matter that leads to the quiet miracle of a stable star. The Cosmic Tornado is a storm, yes. But it is a storm that leaves behind the calm of creation, a chaotic crucible from which worlds, and perhaps life itself, will eventually emerge. In watching it spin, we are watching the universe breathe, exhale, and create.

Reference:

- https://www.onlygoodnewsdaily.com/post/jwst-snaps-cosmic-tornado-from-star-s-birth

- https://www.sci.news/astronomy/webb-protostellar-outflows-serpens-nebula-13037.html

- https://www.discovermagazine.com/jwst-catches-lucky-alignment-of-the-cosmic-tornado-and-a-spiral-galaxy-47308

- https://www.sci.news/astronomy/webb-herbig-haro-object-hh-30-13647.html

- https://www.techtimes.com/articles/299267/20231130/nasa-james-webb-space-telescope-captures-new-breathtaking-display-star.htm

- https://esawebb.org/news/weic2322/

- https://www.universetoday.com/articles/jwst-reveals-a-newly-forming-double-protostar

- https://www.azoquantum.com/News.aspx?newsID=9804

- https://www.astronomy.com/science/webb-captures-an-infant-stars-outflow/

- https://mashable.com/article/james-webb-space-telescope-herbig-haro-object-images

- https://www.thebrighterside.news/post/nasas-webb-telescope-reveals-cosmic-tornado-in-action/

- https://science.nasa.gov/multimedia/2026-nasa-science-calendar/

- https://www.nasa.gov/missions/webb/webb-telescope-a-prominent-protostar-in-perseus/

- https://www.sci.news/astronomy/young-protostar-molecular-outflows-12269.html

- https://www.space.com/james-webb-space-telescope-herbig-haro-object-nov-2023

- https://www.iflscience.com/incredible-new-jwst-image-looks-like-art-what-does-it-actually-show-71774

- https://www.mpg.de/20841037/0915-astr-jwst-hh211-150980-x