In the sun-scorched expanse of the Khaybar Oasis, surrounded by the stark black basalt of the Harrat Khaybar volcanic field, a ghost has risen from the sands. For millennia, the narrative of the Arabian Peninsula during the Bronze Age was one of wandering nomads and ephemeral campsites, a sharp contrast to the towering ziggurats of Mesopotamia or the pyramids of Egypt rising in the distance. But the recent unearthing of Al-Natah, a fortified town hidden for 4,000 years, has shattered that silence.

This is not merely a discovery of stone and pottery; it is the recovery of a lost chapter of human history. The uncovering of Al-Natah reveals a distinct, indigenous path to civilization known as "slow urbanism," challenging everything we thought we knew about how human society evolved in one of the earth's harshest environments.

The Awakening of Khaybar: A Discovery for the Ages

The story of Al-Natah’s discovery begins not with a single shovel entering the earth, but with a high-tech collaboration that spans continents. The Khaybar Longue Durée Archaeological Project, a joint initiative between the Royal Commission for AlUla (RCU), the French Agency for AlUla Development (AFALULA), and the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), set out to map the human history of the Khaybar Oasis.

Khaybar itself is a geological wonder. It is a verdant speck of green trapped within a sea of volcanic lava flows in northwestern Saudi Arabia. For centuries, it was known for its later Islamic history and its strategic importance as a stopping point on caravan routes. However, beneath the layers of later occupation and the protective blanket of basalt rocks, something far older was waiting.

Led by French archaeologist Guillaume Charloux and Saudi researcher Munirah Almushawh, the team utilized aerial surveying and targeted excavations to peel back the layers of time. In late 2024, their findings were published in the journal PLOS ONE, sending ripples through the global archaeological community. They had identified a distinct, fortified settlement spanning approximately 2.6 hectares (roughly 6.4 acres), occupied from approximately 2400 BCE to 1500 BCE.

They named it Al-Natah.

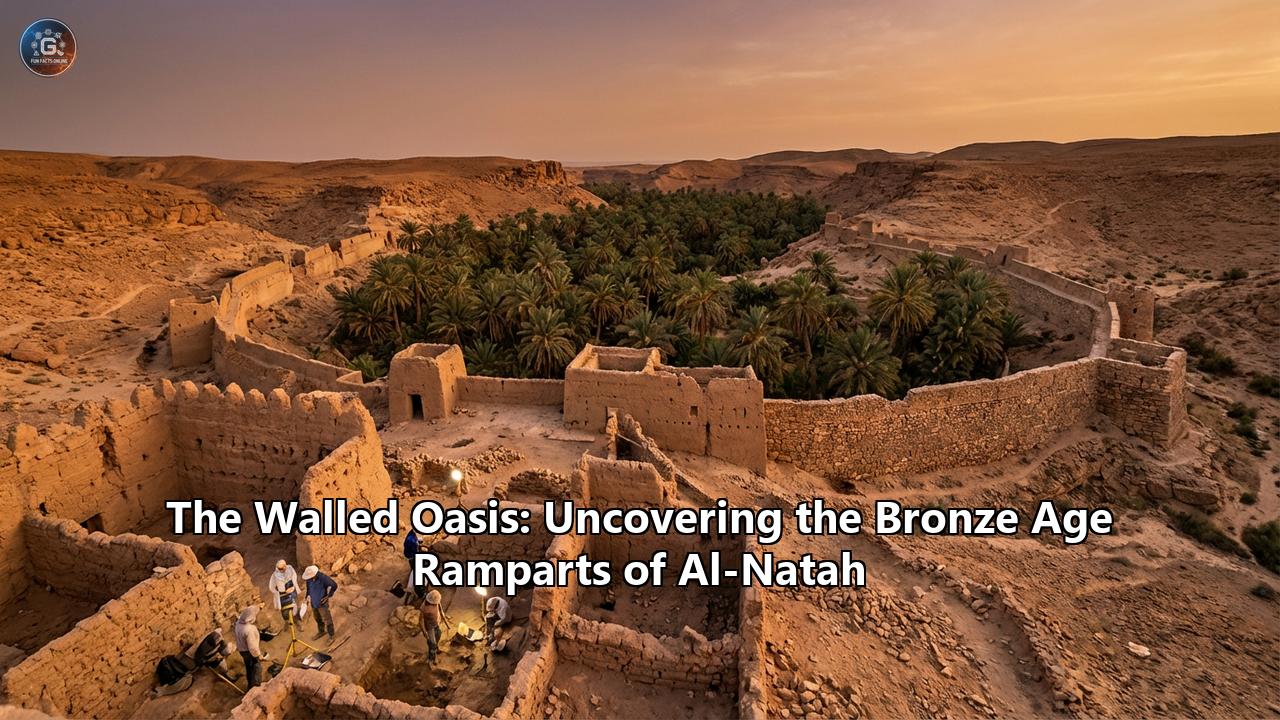

The Fortress in the Oasis: Architectural Marvels of the Bronze Age

To understand the magnitude of Al-Natah, one must visualize the landscape of 2400 BCE. While the empires of the Nile and the Tigris-Euphrates were building monumental temples to god-kings, the people of Al-Natah were engaging in a quieter, yet equally impressive feat of engineering: mastering the desert.

The settlement is not just a cluster of houses; it is a fortress.

The Great Ramparts

The defining feature of Al-Natah is its defensive architecture. The town was protected by massive ramparts that encircled the residential core. These were not simple garden walls but formidable barriers standing up to five meters (16 feet) high and ranging from 3.5 to 6 meters in width.

But the fortification did not stop at the town borders. The discovery revealed a connection to a staggering 14.5-kilometer (9-mile) outer wall that enclosed the entire oasis. This suggests a sophisticated understanding of territorial defense. The people of Al-Natah were not just protecting their homes; they were protecting their livelihood—the fertile soil and water sources of the oasis—from the encroachment of nomadic raiders or rival groups.

Urban Zoning and Planning

Al-Natah defies the stereotype of chaotic tribal settlements. The excavation revealed a high degree of urban planning, a hallmark of civilized society. The town was meticulously divided into distinct functional zones:

- The Residential District: At the heart of the town lay a cluster of roughly 50 dwellings. These homes were built using standard architectural plans, suggesting a unified culture or perhaps a central authority that dictated building codes. Narrow, winding streets connected these homes, creating a close-knit urban fabric where neighbors lived, worked, and socialized in close quarters.

- The Administrative Core: In the central district, archaeologists uncovered the foundations of two larger buildings. Their size and placement suggest they served public or administrative functions—perhaps the seat of a local chieftain, a council meeting place, or a communal storage facility for grain.

- The Necropolis: To the west of the central area lay the city of the dead. This necropolis contained "stepped tower tombs," high circular structures that would have been visible markers of lineage and status. The presence of such elaborate burial sites indicates a society that honored its ancestors and had complex beliefs about the afterlife.

Life Behind the Walls: The People of Al-Natah

Who were the 500 souls that called Al-Natah home? Through the debris of their daily lives—pottery shards, stone tools, and weapons—we can reconstruct a vivid picture of their existence.

A Society in Transition

The population of Al-Natah represents a bridge between two worlds. They were neither fully nomadic wanderers nor residents of a sprawling metropolis like Uruk. They were agropastoralists. While they kept herds of sheep and goats, likely moving them seasonally, they were anchored to the oasis by agriculture.

Soil analysis and finding of grinding stones indicate that they cultivated cereals, likely barley or wheat, right there in the oasis. They baked bread, brewed beer, and stored surplus food for lean times. This ability to store food is the cornerstone of sedentary life, allowing populations to grow and social complexity to deepen.

Craftsmanship and Warfare

The artifacts found in the necropolis paint a picture of a people who were skilled, connected, and armed. The tombs yielded metal weapons, including copper or bronze axes and daggers. This metallurgy confirms that Al-Natah was not isolated; they had access to trade networks that brought metal ores from distant mountains, perhaps from Oman or the Levant.

Alongside weapons, archaeologists found semi-precious stones like agate. These were likely used for jewelry or seals, indicating an appreciation for beauty and status. The pottery found in the residential areas, described by Charloux as "very pretty but very simple," suggests a relatively egalitarian society. Unlike the stratified empires of the north where kings hoarded vast wealth, the people of Al-Natah seem to have shared a more communal standard of living, though the tower tombs hint that some families certainly held more prestige than others.

"Slow Urbanism": Rewriting the Rulebook of Civilization

Perhaps the most significant contribution of the Al-Natah discovery is the theoretical earthquake it has caused in archaeology. For decades, the "urban revolution" was viewed through a single lens: the rapid, explosive growth of cities seen in Mesopotamia and Egypt. In those regions, urbanization was a fast process (archaeologically speaking), driven by massive agricultural surpluses, centralized bureaucracies, and divine kingship.

Al-Natah offers a different model: Slow Urbanism.

In the harsh environment of the Arabian Desert, rapid urbanization was neither possible nor sustainable. Resources were scarce, and the environment was unpredictable. Instead of rushing to build massive cities, the people of Northern Arabia adopted a gradual approach.

- Low Urbanization: Al-Natah was a "small town" of 500 people, not a city of 50,000. It represents a successful adaptation where settlements remained small, manageable, and resilient.

- The Walled Oasis Phenomenon: The town was part of a larger network. We now know that Northwestern Arabia was dotted with these "walled oases" (like Tayma and Qurayyah). They acted as islands of stability in a sea of nomadism, fortified waypoints that facilitated trade and interaction.

- Indigenous Development: This was not a culture imported from Mesopotamia. The architecture, the pottery, and the burial customs are distinct. The people of Al-Natah developed their own solutions to the challenges of their environment, creating a unique Arabian Bronze Age culture.

The Mystery of the Vanishing: Why Was Al-Natah Abandoned?

Around 1500 BCE to 1300 BCE, the streets of Al-Natah fell silent. The roofs collapsed, the ramparts began to crumble, and the desert sands started their slow invasion. The town was abandoned, and for reasons that remain one of the site’s greatest mysteries.

Why did a successful settlement, occupied for nearly a millennium, cease to exist?

- Climate Change: The Bronze Age saw several periods of rapid climate fluctuation. A shift toward even more arid conditions could have dried up the oasis water sources, making agriculture impossible.

- The Shift in Trade: The Late Bronze Age was a time of geopolitical upheaval. The routes that carried copper and stones might have shifted, bypassing Khaybar and cutting off Al-Natah’s economic lifeline.

- Conflict: While the walls were high, they were not invincible. Did a rival group, perhaps early Bedouin tribes or invaders from the north, finally breach the defenses?

- Disease: In a small, enclosed community, an epidemic could have been devastating, forcing the survivors to flee back to the safety of a nomadic lifestyle.

Whatever the cause, the abandonment of Al-Natah serves as a poignant reminder of the fragility of civilization.

Connecting the Dots: Al-Natah and the Future of Heritage

The discovery of Al-Natah is a crown jewel in the Saudi Vision 2030 initiative, which aims to uncover and preserve the Kingdom's rich pre-Islamic heritage. It transforms the Khaybar Oasis from a location known primarily for medieval history into a focal point of ancient human development.

This site connects Northwestern Arabia to the broader tapestry of the ancient world. It shows that while the Pharaohs were building pyramids, the ancestors of the Arabs were building ramparts. They were taming the desert, forging weapons, and laying the groundwork for the trade routes that would eventually carry frankincense and myrrh to the ends of the earth.

Conclusion: The Oasis that Time Forgot

Al-Natah is more than just a ruin; it is a testament to human resilience. It tells the story of a people who looked at a harsh, volcanic landscape and saw a home. They built walls not just to keep enemies out, but to hold a community together.

As archaeologists continue to sift through the sands of Khaybar, we can expect more secrets to emerge. But one thing is already clear: the history of civilization is not just the story of river valleys and empires. It is also the story of the oasis, the rampart, and the slow, steady march of progress in the heart of the desert. The Walled Oasis of Al-Natah has spoken, and the world is finally listening.

Reference:

- https://tribune.com.pk/story/2507389/archaeologists-uncover-4000-year-old-fortified-town-in-saudi-arabia

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39475942/

- https://www.traveldailymedia.com/archaeologists-discover-al-natah-in-the-khaybar-oasis-of-north-west-arabia/

- https://archaeologymag.com/2024/10/bronze-age-settlement-discovered-in-saudi-arabian-oasis/

- https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0309963

- https://www.rcu.gov.sa/en/strategic-initiatives/khaybar-alula

- https://archaeology.org/news/2024/11/01/bronze-age-settlement-excavated-in-saudi-arabia/

- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/bronze-age-town-tombs-hidden-saudi-arabia-oasis-al-natah/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al-Natah

- https://www.jpost.com/archaeology/archaeology-around-the-world/article-827012

- https://www.thenationalnews.com/news/2024/10/30/discovery-of-bronze-age-settlement-suggests-northern-arabia-was-slow-to-urbanise/

- https://revistapesquisa.fapesp.br/en/life-in-an-oasis-during-the-bronze-age/

- https://www.orient-mediterranee.com/activity/a-bronze-age-town-in-the-khaybar-walled-oasis-debating-early-urbanization-in-northwestern-arabia/

- https://www.sci.news/archaeology/bronze-age-town-al-natah-13389.html

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11524520/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392952534_The_Walled_Oases_Complex_in_north-west_Arabia_evidence_for_a_long-term_settlement_model_in_the_desert