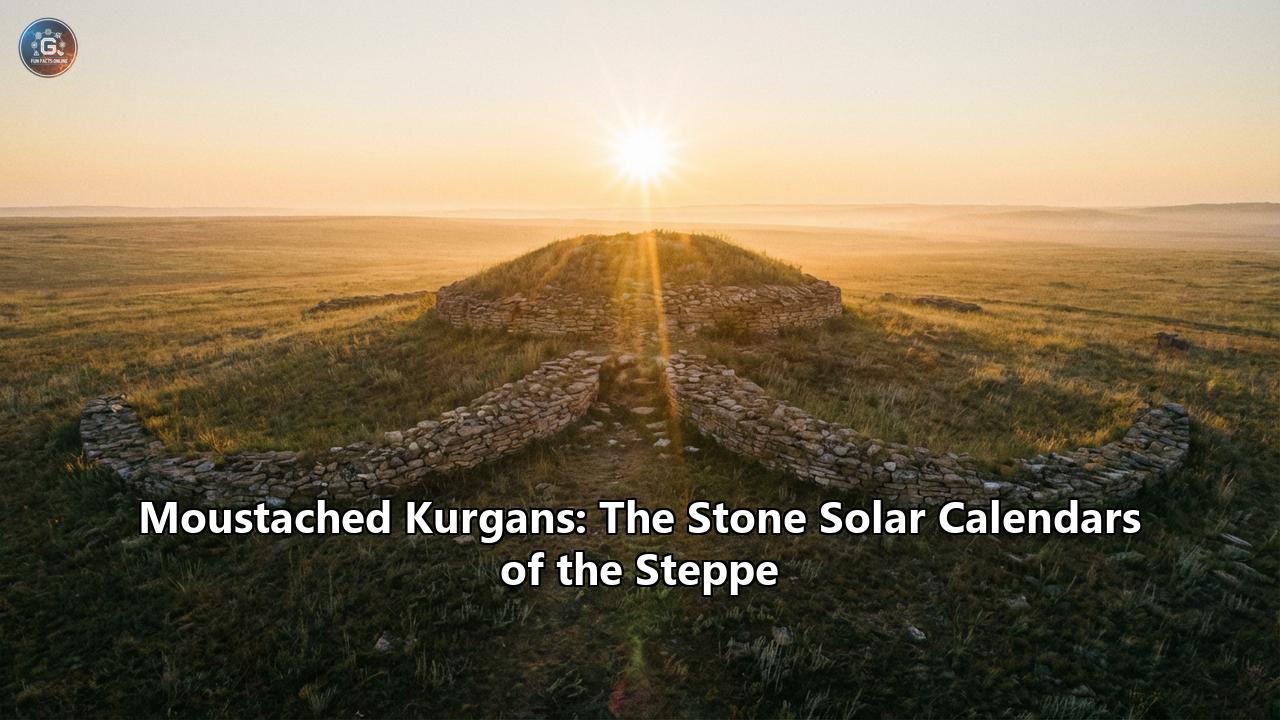

The wind on the Saryarka steppe does not just blow; it scours. It rushes across the endless, golden plains of Central Kazakhstan, whispering through the feather grass and eroding the memory of empires that once called this vast ocean of land home. But amidst this emptiness, defying the erasing wind, lie peculiar formations of stone that have puzzled travelers and shepherds for centuries. From the ground, they appear as mere piles of rubble, chaotic and formless. But seen from above—or through the eyes of the ancient astronomers who built them—they reveal a stunning geometry: a central mound flanked by two long, elegant arcs of stone curving eastward, like the whiskers of a great beast or the wings of a soaring bird.

These are the "Moustached Kurgans," the stone solar calendars of the steppe. For decades, they were dismissed as mere curiosities of the ancient nomadic world. Today, however, archaeology is revealing them to be one of the most sophisticated Archaeoastronomical instruments of the ancient world—a monumental testament to a people who navigated the sea of grass by reading the map of the stars.

The Anatomy of a Mystery

To understand a Moustached Kurgan, one must first discard the image of a simple grave. While they are indeed burial sites, their architecture suggests a function far more complex than a mere container for the dead.

The classic complex, primarily associated with the Tasmola culture of the Early Iron Age (8th–5th centuries BC), follows a strict and fascinating blueprint. It begins with a primary burial mound, or kurgan, often built of stone and earth. To its immediate east, there is frequently a smaller satellite mound. But the defining feature—the "moustache"—extends from this eastern side.

Two distinct ridges of stone, sometimes paved and curbed with larger slabs, curve outward and eastward from the central mounds. These ridges can range from a modest 20 meters to a staggering 200 meters in length. At their eastern terminals, they often end in small circular stone constructions or "discs."

When viewed from the air, the shape is unmistakable. Some see a moustache, hence the name. Others see a heart shape, a pair of horns, or a bird in flight. But for the Tasmola architects, this shape was not merely aesthetic; it was a machine made of rock.

The Stone Compass of the Tasmola

The Saryarka region is a land of extremes. Winters are brutal and freezing; summers are scorching. For the nomadic pastoralists of the Tasmola culture, survival depended entirely on timing. Moving herds to the wrong pasture too early could mean starvation in a late frost; moving too late could mean withered grass and drought. They needed a clock that never failed.

They built one into the earth itself.

Archaeologists and astronomers have spent years measuring the alignments of these stone ridges. The results are undeniable. In many of the examined complexes, the "moustaches" function as a solar observatory.

If an observer stands at the western edge of the complex—usually atop the primary burial mound—and looks down the length of the curved stone ridges, they are looking at a calendar.

- The Winter Solstice: One ridge often aligns perfectly with the point on the horizon where the sun rises on the shortest day of the year.

- The Summer Solstice: The opposing ridge points to the sunrise on the longest day of the year.

- The Equinoxes: The central axis between the two ridges often marks the sunrise on the days when night and day are equal—the crucial turning points of spring and autumn.

This was not primitive guesswork. It was precision engineering. By marking these specific solar events, the Tasmola chieftains could predict the changing of the seasons with absolute certainty, signaling the time for the great seasonal migrations that kept their society alive.

The Lords of the Steppe

Who were the architects of these stone computers? The Tasmola culture was a distinct branch of the broader Saka (Scythian) world—the fearsome, gold-adorned horse lords who dominated the Eurasian steppe for centuries.

Excavations at sites like Taldy-2 and Karashoky have peeled back the layers of history to reveal a society of immense wealth and artistry. These were not destitute wanderers. The kurgans often contain elite burials: warriors laid to rest with iron daggers and bronze arrowheads, and nobles adorned in gold.

The "Animal Style" art found in these tombs is breathtaking. Gold plaques depict crouched stags with exaggerated antlers, coiled snow leopards, and griffins—predators and prey locked in an eternal, golden dance. This art reflects their reality: a world of motion, violence, and natural beauty.

Interestingly, many Moustached Kurgans are cenotaphs—empty tombs. They contain pottery, evidence of ritual fires, and horse skeletons (sacrificed to carry the master to the afterlife), but no human body. This suggests that the "Moustached" complex was perhaps a shrine to a fallen hero whose body was lost in a distant war, or a purely ritualistic site dedicated to the sun god, where the "burial" was symbolic—a temple rather than a tomb.

The Medieval "Renaissance"

The story of the Moustached Kurgans has recently become even more intriguing. For a long time, it was believed that this tradition died out with the Saka tribes before the Common Era. However, discoveries in the Ulytau region in 2024 have thrown a wrench into the timeline.

Archaeologists uncovered "moustached" kurgans dating not to the Iron Age, but to the Medieval period (6th–15th centuries AD). These later constructions, built by Turkic nomads or their successors before the Mongol conquest, show a fascinating evolution of the form. Some of these medieval mounds feature ridges that cross the mound in an "X" pattern, differing from the classic eastern arcs of the Tasmola.

This discovery implies a profound cultural continuity. It suggests that the nomads of the Middle Ages, though separated from the Tasmola builders by a thousand years, still looked at the landscape with the same eyes. They respected the old monuments, perhaps reusing them or mimicking their sacred architecture to claim legitimacy and connection to the ancestors of the land. The "moustache" was not just a tool; it had become a symbol of power and memory that transcended time.

Guardians of Time

Today, over 400 of these stone complexes have been documented across Central Kazakhstan. They stand silent, their ridges often sunken into the turf, visible only as subtle undulations in the grass.

They remind us that the "empty" steppe was never truly empty. It was a landscape alive with meaning, mapped by the stars and anchored by stone. The Moustached Kurgans were the cathedrals and the universities of the nomad. They were places where the sky touched the earth, where the sun was tamed, and where the people of the wind anchored themselves in the flow of eternity.

When you look at a Moustached Kurgan, you are not just looking at a grave. You are looking through the viewfinder of an ancient camera, focused on the horizon, waiting for a sunrise that has been greeted with reverence for three thousand years.

Reference:

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Tasmola-Kurgans-in-Aiyrtas-Valley-in-Central-Beisenov-Shashenov/304a996969619610eaa39237a6c57dae024f032d

- https://archaeologymag.com/2024/09/centuries-old-mustached-burial-found-in-kazakhstan/

- https://www.livescience.com/archaeology/mustached-burial-mounds-from-the-middle-ages-found-in-kazakhstan

- https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/mustached-kurgans-0021386