For over half a century, the backbone of our digital civilization has been silica. From the first blurry transmissions of the 1970s to the hyper-connected, cloud-native world of the 2020s, the Standard Single-Mode Fiber (SMF) has been the unshakeable monarch of telecommunications. It is a marvel of materials science: a strand of ultra-pure glass, doped with germanium, capable of trapping light via Total Internal Reflection and guiding it across oceans.

But glass, for all its purity, has a fundamental flaw. It is matter. And when light travels through matter, it pays a tax. It slows down—trudging through silica at roughly two-thirds the speed of light in a vacuum. It scatters—colliding with the microscopic density fluctuations inherent in the glass structure (Rayleigh scattering), which sets a hard physical limit on how clear a solid fiber can ever be. And it distorts—succumbing to nonlinear effects like the Kerr effect when intensities get too high, turning clear signals into noise.

For decades, engineers hit a wall. They had refined silica to its atomic limits. They had dropped attenuation to 0.14 dB/km, a number that hadn't budged significantly since the 1980s. The "Glass Ceiling" was reached.

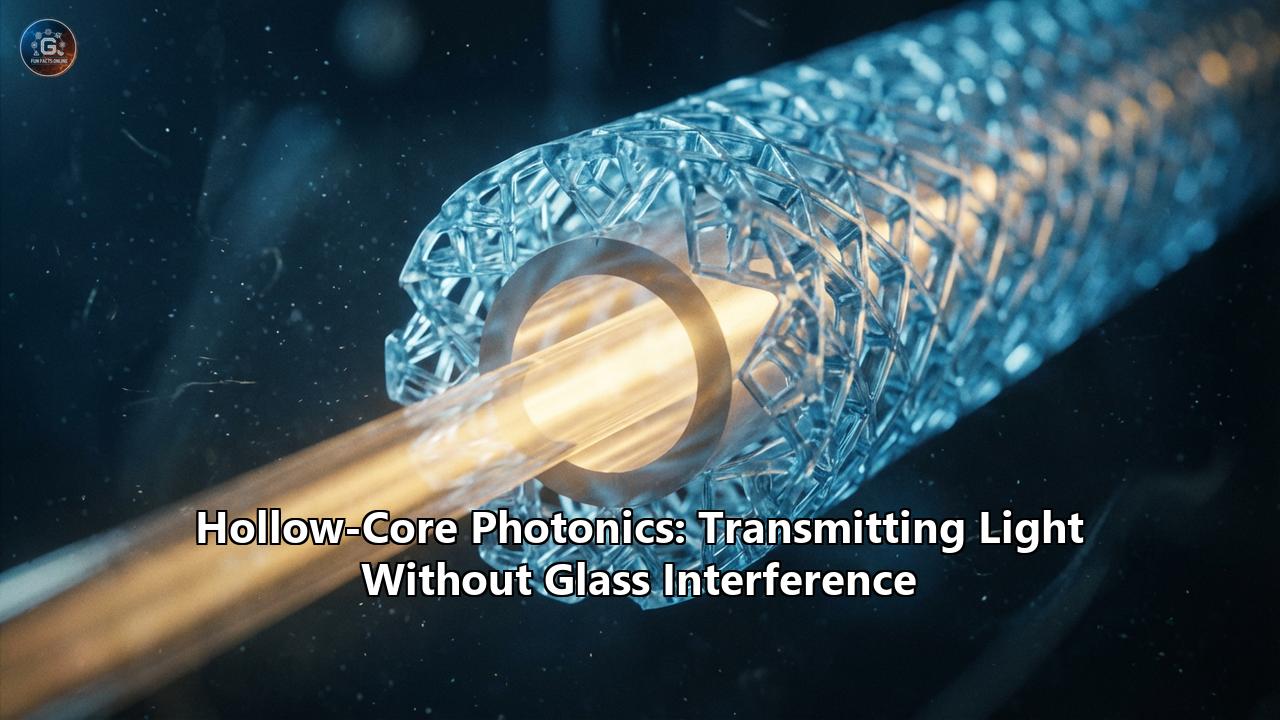

Then, a radical idea took hold: What if the best medium for transmitting light wasn't a better glass, but no glass at all?

Enter the world of Hollow-Core Photonics. This is the story of how scientists learned to guide light through a vacuum, breaking the speed limit of the internet, shattering the theoretical limits of signal loss, and opening the door to a new era of quantum computing, industrial power, and artificial intelligence.

Chapter 1: The Physics of Nothing

To understand why hollow-core fiber (HCF) is revolutionary, one must first understand the difficulty of the task. Light, by its nature, wants to spread out. In a vacuum or air, there is no "cladding" with a lower refractive index to bounce the light back into the core, as there is in traditional solid fibers. If you shine a laser down a simple copper pipe or a glass capillary, the light grazes the walls, is absorbed by the material, and dies out within centimeters.

To trap light in an air core for kilometers requires tricking the photons. Over the last thirty years, three distinct mechanisms have been developed to achieve this, evolving from complex theory to commercially viable reality.

1. The Photonic Bandgap (PBG) Effect

The first major breakthrough came in the 1990s with the invention of the Photonic Crystal Fiber (PCF). Early designs used a "bandgap" effect. Imagine a honeycomb lattice of air holes in glass surrounding a hollow core. This periodic structure acts like a crystal for photons. Just as a semiconductor crystal forbids electrons from having certain energies (an electronic bandgap), this periodic glass-air structure forbids light of certain wavelengths from existing in the cladding.

When light of the correct color tries to escape the hollow core, it hits the cladding and finds it "forbidden." Unable to propagate through the lattice, it is forced back into the core. PBG fibers were the first to demonstrate true air-guiding, but they suffered from narrow bandwidths (they only worked for specific colors) and relatively high scattering loss due to surface roughness at the core-cladding interface.

2. The Anti-Resonant Reflecting Optical Waveguide (ARROW)

As research progressed, a more robust mechanism emerged: Anti-Resonance. Instead of relying on a perfect crystal lattice, these fibers rely on the constructive and destructive interference of light passing through thin glass membranes.

Think of the thin glass wall surrounding the air core as a Fabry-Perot resonator. For specific wavelengths (resonant wavelengths), the glass wall is transparent, and light leaks out. But for other wavelengths (anti-resonant), the glass wall acts as a highly perfect mirror, reflecting the light back into the air core. This is the Anti-Resonant Hollow-Core Fiber (AR-HCF).

Unlike PBG fibers, AR-HCFs have enormous transmission windows—spanning from the ultraviolet to the mid-infrared. The light isn't trapped by a crystal lattice; it is trapped by a "cage" of thin glass mirrors.

3. The Endgame: NANF and DNANF

The modern champion of this technology is the Nested Antiresonant Nodeless Fiber (NANF).

Early anti-resonant designs had a problem: "nodes." These were points where the glass tubes touching the outer cladding created junctions. Nodes are lossy; they allow light to couple into the glass and leak away. The solution was the "Nodeless" design—a ring of non-touching glass tubes floating inside the outer jacket.

But light could still leak through the tubes. The solution to that was "Nesting." By placing a smaller tube inside each outer tube (like a Russian doll), researchers created a second reflective barrier. If light manages to tunnel through the first mirror, the second mirror catches it and bounces it back.

This evolved into the Double Nested Antiresonant Nodeless Fiber (DNANF). In this geometry, the light is confined so effectively that less than 1 part in 10,000 of the optical power travels in the glass. The rest travels in pure air (or vacuum). This structure recently allowed researchers at the University of Southampton (and later Microsoft's Lumenisity) to achieve loss rates of 0.091 dB/km—shattering the fundamental limit of solid silica.

Chapter 2: A History of Holes

The journey to the 0.091 dB/km record was not a straight line; it was a winding path of accidental discoveries and stubborn persistence.

It began in 1991, at a conference in the United States. Philip Russell, a professor at the University of Southampton (and later founding director of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Light), had a moment of inspiration. While bored during a talk, he sketched a honeycomb structure of glass and air, wondering if the newly theorized "photonic bandgaps" could be applied to optical fibers.

Russell’s sketch led to the fabrication of the first "holey" fiber, or Photonic Crystal Fiber (PCF), later that decade. However, the first PCFs were solid-core; the holes merely lowered the cladding's refractive index. It wasn't until 1999 that Russell’s team successfully guided light in a hollow core using the bandgap effect. It was a scientific marvel: the core glowed with a brilliant, unearthly mode of light, guided by air.

However, the "Loss Wars" had just begun. Early hollow-core fibers had losses measured in decibels per meter—millions of times worse than standard telecom fiber. They were scientific curiosities, useless for long-distance communication.

Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, two camps emerged. The PBG Camp tried to perfect the honeycomb lattice, achieving losses around 1.2 dB/km. But they hit a wall; the surface scattering from the intricate honeycomb was too high. The Kagome Camp (named after the Star of David basket-weave pattern) explored anti-resonance. The Kagome fibers were broadband but lossy.

The turning point came around 2014-2015, when Francesco Poletti and his team at Southampton proposed the NANF structure. They abandoned the complex honeycomb and the Kagome lattice in favor of simplified, non-touching tubes. Theory predicted this would decouple the light from the noisy glass almost entirely.

It took years to figure out how to manufacture these delicate "nested" structures without them collapsing, but by the early 2020s, the prediction held true. The loss numbers plummeted: from 1 dB/km, to 0.28 dB/km, and finally, in 2024/2025, breaking the 0.1 dB/km barrier. The "useless curiosity" had beaten the reigning champion of materials science.

Chapter 3: The Need for Speed (Latency)

While the low-loss record is the scientific crown jewel, the speed of hollow-core fiber is what instantly captivated the financial and computing industries.

In standard glass fiber, light travels at $c/n$, where $c$ is the speed of light in a vacuum and $n$ is the refractive index. For silica, $n \approx 1.45$. This means light lumbers along at roughly 200,000 km/s.

In a hollow-core fiber, the light travels through air ($n \approx 1.0003$). The speed is effectively $c$, or roughly 300,000 km/s.

This is a 47% speed increase.In terms of latency, this equates to a saving of roughly 1.5 microseconds for every kilometer of cable. To a human, this is nothing. To a High-Frequency Trading (HFT) algorithm, it is an eternity.

The Wall Street Race

The first adopters of early (and expensive) hollow-core fibers were HFT firms. In the ruthless world of arbitrage, if you can see a price change in Chicago and execute a trade in New York faster than your competitor, you print money. Firms spent millions digging straighter trenches to shave off microseconds. Hollow-core fiber offered a way to slash milliseconds without moving mountains. A hollow-core link between London and Frankfurt, or New Jersey and Chicago, became the "gold standard" of trading infrastructure.

The AI Interconnect

However, the niche HFT market was just the proving ground. The explosive rise of Artificial Intelligence created a new, far larger demand for low latency.

Modern AI models (like GPT-4 and its successors) are trained on massive clusters of GPUs—tens of thousands of processors acting as a single supercomputer. These GPUs must constantly exchange vast amounts of data (gradients, parameters) to stay synchronized. If the network connecting them is slow, the expensive GPUs sit idle, waiting for data.

This is why Microsoft acquired Lumenisity in late 2022. They realized that to build the Azure supercomputers of the future, they needed to eliminate the "glass latency" within the data center. By deploying hollow-core fibers to connect racks and data halls, Microsoft reduces the "tail latency" of training runs, making their AI clusters significantly more efficient. The announcement of a 15,000 km deployment of hollow-core fiber in 2024 was not just an upgrade; it was a change in the fundamental physics of the cloud.

Chapter 4: Power, Purity, and the Spectrum

Beyond speed and loss, hollow-core fibers possess "superpowers" that solid glass can never emulate.

1. The Power of Air

In a solid fiber, if you pump too much laser power, the glass heats up. Eventually, it melts or shatters (thermal fuse). Even before that, the high intensity triggers nonlinear effects. The Kerr effect causes the refractive index of the glass to change with intensity, muddling the signal. Brillouin scattering causes the light to reflect backward, potentially destroying the laser source.

In HCF, the light travels through air. Air is thousands of times less nonlinear than glass. You can pump kilowatts of peak power—enough to cut steel—through a hair-thin HCF, and the fiber remains cool. This makes HCF ideal for industrial laser delivery. Currently, high-power cutting lasers rely on complex mirror arms or bulky fibers. HCF allows flexible, robot-mounted delivery of ultra-short pulse lasers (femtosecond lasers) for precision micro-machining, eye surgery, and drilling, without the pulse stretching or distorting.

2. The Full Spectrum

Silica glass is transparent in the visible and near-infrared, but it turns opaque in the mid-infrared (beyond 2 microns) and the ultraviolet. It absorbs those wavelengths heavily.

Because HCF guides light in a hole, the material of the cladding matters much less. Light that would normally be absorbed by glass can be guided through an HCF with minimal loss because it barely touches the walls. This opens up the Mid-Infrared window (2μm - 10μm), a region critical for identifying chemical signatures (molecular fingerprinting) and thermal imaging. HCFs are now enabling laser surgeries using wavelengths (like the 2.94 μm Er:YAG laser) that are absorbed by water and bone but couldn't previously be delivered via flexible fiber.

Chapter 5: Manufacturing the Impossible

How do you build a glass tube that contains smaller glass tubes, which contain even smaller glass tubes, all suspended in a specific geometry, drawn out to the thickness of a human hair, over kilometers of length?

The manufacturing of NANF and DNANF is a feat of engineering that rivals semiconductor fabrication.

The Stack-and-Draw Technique

The process often starts with "stack-and-draw." Engineers hand-assemble a "preform" on a macroscopic scale. They take glass tubes (centimeters in diameter) and stack them inside a larger glass tube to create the desired geometry (the nesting, the anti-resonant tubes).

This preform, which might be nearly a meter long and 5-10 cm wide, is placed in a fiber draw tower. It is heated to roughly 2000°C. Gravity takes over. The glass softens and drips, pulling the structure down into a thin thread.

The Pressure Control Challenge

The nightmare of HCF fabrication is keeping the holes open. Surface tension wants to collapse the molten glass into a solid wire. To prevent this, manufacturers must pressurize the internal holes with inert gas during the draw.

But not all holes are the same. The central core needs one pressure; the cladding tubes need another. If the pressure is too high, the tubes blow up like balloons. If too low, they collapse. The "recipe" for drawing a Double Nested Antiresonant Nodeless Fiber involves precise, active control of multiple pressure zones while the fiber is being pulled at speeds of tens of meters per minute.

The Splicing Nightmare

Once the fiber is made, you have to connect it. Splicing standard fiber involves pushing two glass rods together and melting them with an electric arc. If you do that to HCF, you melt the delicate micro-structure, collapsing the holes and blocking the light.

This was a major hurdle for commercialization. The solution involved developing specialized splicers that use lower temperatures, "tack" fusion (fusing only the outer ring), or glue-free mechanical connectors. Additionally, to stop air and moisture from entering the core (which would degrade performance), the ends must often be hermetically sealed or angled-cleaved to prevent back-reflections.

Chapter 6: The Quantum and Sensing Frontier

Hollow-core fiber is not just a pipe; it is a test tube. Because the core is empty, it can be filled.

Gas Sensing

By pumping a gas (like methane or carbon dioxide) into the core and shining a laser through it, the fiber becomes a sensor. Because the light travels inside the gas for kilometers, the interaction path is incredibly long. This allows for the detection of trace gases at parts-per-billion concentrations—vital for environmental monitoring or breath analysis for disease detection.

Quantum Computing

Perhaps the most sci-fi application is in quantum technologies. Researchers are filling these fibers with alkali metal vapors (like Rubidium or Cesium). When laser light interacts with these atoms inside the confined core, it can generate "Rydberg states"—highly excited atoms that are sensitive to electric fields.

This setup creates a room-temperature quantum memory or a high-precision quantum sensor. Instead of requiring a room-sized vacuum chamber and optical table to trap atoms, the "experiment" is contained inside a flexible fiber that can be coiled into a small box. This is a critical step toward miniaturizing quantum computers and quantum internet repeaters.

The Ultimate Gyroscope

Fiber Optic Gyroscopes (FOGs) are used to navigate aircraft, submarines, and satellites. They work by sending light in two directions around a coil; rotation causes a phase shift (Sagnac effect). Standard FOGs suffer from thermal drift because the refractive index of glass changes with temperature.

HCFs are "thermal insensitive." Air's refractive index barely changes with temperature. HCF-based gyroscopes are proving to be vastly more stable than their solid-core counterparts, promising a new generation of inertial navigation systems that allow submarines to navigate for months without surfacing for GPS.

Chapter 7: The Commercial Landscape

The transition from lab bench to global infrastructure is currently underway, driven by heavyweights.

Lumenisity (Microsoft): The current leader in low-loss HCF. Their acquisition by Microsoft was the signal to the industry that HCF is "real." They are currently manufacturing the DNANF cables being laid in Azure data centers. OFS / Furukawa: A titan of the optical fiber world, OFS has deep research into hollow-core designs, particularly for industrial laser delivery and sensing applications. NKT Photonics: Based in Denmark, they are pioneers in Photonic Crystal Fibers. While they focus heavily on the "supercontinuum" laser market (generating white laser light), their hollow-core technology is standard for scientific and medical research. Corning & Heraeus: The sleeping giants have awoken. Corning, the inventor of low-loss silica fiber, is now partnering with Microsoft to scale the manufacturing of hollow-core preforms and fibers. Heraeus provides the ultra-pure silica tubes required for the preforms. The supply chain is industrializing. China Mobile / YOFC: In late 2024, Chinese manufacturers announced their own record-breaking deployments and lab results, signaling that the race for "air-guiding supremacy" is now a geopolitical tech race.Chapter 8: The Future Outlook

Will hollow-core fiber replace all fiber?

Probably not. The cost of manufacturing HCF—with its complex preforms and slow draw speeds—is significantly higher than standard SMF, which is drawn at speeds of 2-3 km per minute and costs pennies per meter. For connecting your home to the internet (FTTH), standard glass is good enough and cheap enough.

However, HCF will likely become the standard for:

- Data Center Interconnects (DCI): Where latency and massive bandwidth density are king.

- Backbone Networks: The "super-highways" between major cities where the 30% latency reduction is worth the premium.

- Transoceanic Cables (Future): While not yet ready for the pressure of the ocean floor, the low-loss record suggests that future transatlantic cables could be hollow, shaving roughly 15-20 milliseconds off the London-NY round trip—a lifetime in the digital economy.

There are still hurdles. Cabling HCF is tricky (it's sensitive to being crushed). Connector standards need to be written. But the physics is settled. The era of relying solely on solid glass is over.

Conclusion: The Age of Air

We are witnessing a rare event in technology: a fundamental shift in the physical medium of communication. For 50 years, we improved the glass. Now, we are removing it.

Hollow-core photonics represents the ultimate optimization. By guiding light through air, we have returned to the medium it travels best in, while retaining the guidance and control of a fiber. It is a technology that combines the speed of radio waves with the bandwidth of fiber optics.

As Microsoft lays thousands of kilometers of these "hollow threads" to power the AI revolution, and as quantum physicists use them to trap atoms, the hollow-core fiber stands as a testament to human ingenuity. We found the limit of nature's best material, and when we couldn't break the material, we simply removed it. The future of light is empty, and it is faster than ever.

Reference:

- https://www.tomshardware.com/tech-industry/hollow-core-fiber-research-smashes-optical-loss-record

- https://www.networkworld.com/article/4049666/microsofts-hollow-core-fiber-delivers-the-lowest-signal-loss-ever.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=akE2zp-687Q

- https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10059694/1/Hollow%20Core%20Fibres%20and%20their%20Applications.pdf

- https://validate.perfdrive.com/?ssa=cc5c09c1-89b3-43b5-3a55-85c4aecd36a4&ssb=46898231276&ssc=https%3A%2F%2Fopg.optica.org&ssi=b9294fc8-d3hy-d09b-eefe-fdc6a6dc212d&ssk=botmanager_support@radware.com&ssm=57790752710394377136400881984004&ssn=a796c8fcb6922736d6752e98451722b022c3e76ddbf0-6642-8136-ba5547&sso=0885b36-b408-3e0b15506ec8ed9593c355f173395d3e141279a599b95db0&ssp=33866276011768780317176875868269718&ssq=82338568279133426408582790890965954113021&ssr=MTI0LjIxNy4xODkuMTE5&sst=python-requests%2F2.32.3&ssv=&ssw=

- https://www.techspot.com/news/109324-new-hollow-core-fiber-outperforms-glass-pushing-data.html

- https://techblog.comsoc.org/2022/12/13/microsoft-acquires-lumenisity-hollow-core-fiber-high-speed-low-latency-leader/

- https://www.fierce-network.com/broadband/microsoft-strikes-new-deal-corning-boost-its-hollow-core-fiber

- https://www.cordacord.com/news_view.php?id=20241121043014

- https://www.fcst.com/Development-Of-Hollow-Core-Optical-Fiber-Technology-For-Communications-And-Challenges-In-Engineering-Applications-id41375885.html

- https://www.thorlabs.com/hollow-core-photonic-crystal-fibers

- https://cablecommllc.com/fibersplicingchallenges/

- https://ausoptic.com.au/blog/hollow-core-fibre-splicing-low-latency-optical-communication/

- https://www.zion-communication.com/nested-anti-resonant-nodeless-hollow-core-fiber-nanf-guide.html