In the cold, compacted soil of Henan Province, just east of where the great imperial palace of Luoyang once cast its shadow, the earth has finally yielded a secret it kept for fifteen centuries. It did not appear as gold, nor jade, nor the skeletal remains of a forgotten emperor. It appeared as a geometric anomaly—a phantom grid etched into the stratigraphic layers of the Yellow River floodplains.

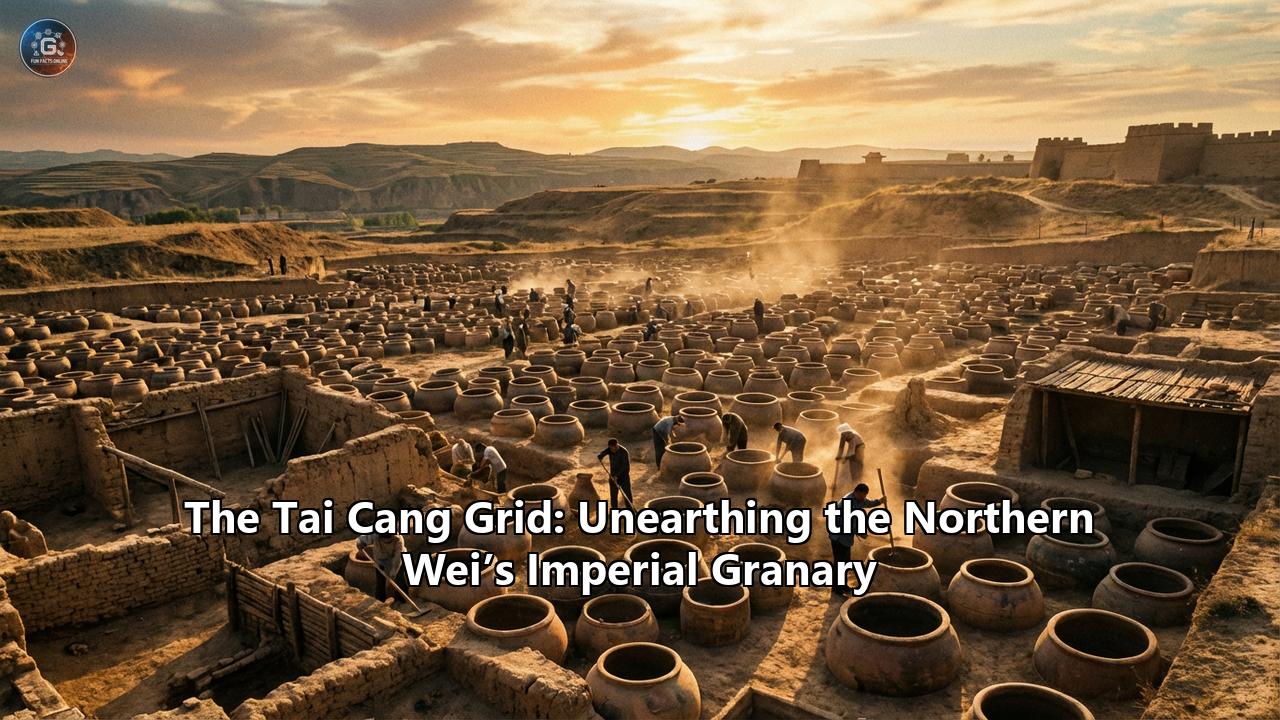

To the untrained eye, it was merely a variation in soil color. To the archaeologists of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, it was a revelation. As the spades dug deeper, removing the overburden of modern industry and the dust of the Tang and Song dynasties, a pattern emerged with startling clarity: row upon row of massive circular pits, aligned with the precision of a military phalanx. Fourteen columns. Twelve rows. One hundred and sixty-eight subterranean silos, silent and empty, staring up at the sky like the eyes of a dormant giant.

This is the Tai Cang—the "Great Granary" of the Northern Wei Dynasty.

For decades, historians have read the Wei Shu (Book of Wei) and the Luoyang Jialan Ji (Record of the Monasteries of Luoyang), dreaming of the city that was once the center of the world. They read of its golden pagodas, its bustling silk markets, and its armies that thundered across the Central Plains. But the logistical heart of that empire—the engine that fed the million souls of Luoyang and fueled the ambitions of the Tuoba emperors—remained a ghost.

Now, the ghost has a shape. It is a grid of 168 circles, a testament to a moment in human history when a nomadic people descended from the steppes, embraced the civilization of the plough, and built a machine of statecraft so vast that its ruins alone are enough to stagger the imagination.

Part I: The Geometry of Survival

The discovery of the Tai Cang is not merely an archaeological footprint; it is a window into the mind of the Northern Wei state. The sheer scale of the excavation site challenges our understanding of ancient engineering.

The 168 pits are not haphazard holes dug by desperate farmers. They are architectural marvels of the 5th century. Each pit measures between 9 and 11 meters in diameter and plunges 4 meters into the earth. In the ancient world, where labor was the primary fuel of construction, the removal of this volume of earth—roughly 60,000 cubic meters of soil—was a monumental undertaking, comparable to the raising of a small pyramid.

But it is the grid that captivates. The silos are arranged with a cardinal precision that mirrors the city of Luoyang itself. In the Northern Wei worldview, order was not just an aesthetic preference; it was a cosmic duty. The emperor, the Son of Heaven, was responsible for aligning the human world with the order of the stars. The Tai Cang, with its strict 14x12 layout, was not just a warehouse; it was a statement of control. It said to the chaotic world of the Northern and Southern Dynasties: Here, there is order. Here, there is a plan.

Inside these pits, the "blood" of the empire was stored. Not blood, but millet—the golden, drought-resistant grain that had sustained Chinese civilization for millennia.

Based on the volumetric analysis of the thirteen pits excavated so far, archaeologists estimate that a single pit could hold approximately 100 cubic meters of grain. In weight, this translates to roughly 120 tonnes of millet per silo. Multiply this by 168. The Tai Cang, when fully stocked, held over 20,000 tonnes of grain.

To put this in perspective: the standard ration for a soldier or a laborer in the Northern Wei was roughly one sheng (about 0.6 liters) of grain per day. The Tai Cang alone could feed a standing army of 100,000 men for nearly a year. It was a strategic reserve of nuclear proportions in an age where famine was the ultimate weapon of mass destruction.

But why bury it?

The genius of the Tai Cang lies in its subterranean design. The Central Plains of China are subject to wild temperature fluctuations—scorching, humid summers and biting, dry winters. Above-ground timber barns were vulnerable to fire, mold, rats, and the rot of humidity. But four meters down, the earth acts as a thermal battery. The temperature remains stable, cool, and dark.

While the organic lining of the Tai Cang pits has largely decayed, comparative analysis with the later Hanjia Granary (built by the Sui and Tang) suggests a sophisticated preservation technology. The walls would have been fire-hardened to create a ceramic-like crust, preventing groundwater seepage. The floor was likely layered with wooden planks, straw mats, and chaff to create an air gap, keeping the grain dry. Finally, the grain itself—millet—is legendary for its longevity. When kept dry and cool, millet can remain edible for decades.

The Tai Cang was not a grocery store; it was a time capsule. It was the empire’s insurance policy against the whims of the Yellow River and the droughts of the heavens. It was the physical manifestation of the Mandate of Heaven—the promise that the Emperor could control time itself, saving the harvest of the fat years to survive the lean ones.

Part II: The Tuoba’s Dream

To understand the Tai Cang, one must understand the men who built it.

The Northern Wei was not a "Chinese" dynasty in the traditional Han sense. It was founded by the Tuoba, a clan of the Xianbei people—nomadic warriors from the steppes of what is now Inner Mongolia and Manchuria. For centuries, their currency was cattle, their home was the yurt, and their god was the open sky.

By the late 5th century, however, the Tuoba had conquered the shattered remnants of northern China. They found themselves ruling over millions of Han Chinese farmers, a people whose lives were dictated not by the migration of herds, but by the sowing and reaping of grain.

The Tuoba rulers faced a crisis of identity and governance. To rule the steppe, you needed a fast horse and a strong bow. To rule the Central Plains, you needed bureaucracy, tax rolls, and, above all, granaries.

Enter Emperor Xiaowen (r. 471–499), one of the most fascinating and radical figures in Chinese history.

Xiaowen was a visionary who believed that for his dynasty to survive, it had to cease being Xianbei and become Chinese. He launched a program of aggressive Sinicization. He banned the wearing of Xianbei clothing at court. He outlawed the Xianbei language for officials under the age of thirty. He forced the Tuoba nobility to adopt Chinese surnames—the royal house of Tuoba became the House of Yuan.

But his boldest move was geographical. In 493 AD, under the pretense of a military campaign against the south, Xiaowen moved his entire court and hundreds of thousands of his people from the northern capital of Pingcheng (modern Datong) to the ancient, ruined capital of Luoyang.

It was a move of staggering audacity. Pingcheng was safe, close to the steppe power base. Luoyang was in the heart of the flood-prone plains, surrounded by potential enemies. But Luoyang was the symbolic center of the universe, the capital of the Eastern Han. To rule from Luoyang was to claim the mantle of legitimate succession to the ancient empires.

The construction of the Tai Cang was a direct result of this move.

When Xiaowen arrived, Luoyang was a shadow of its former self. He ordered it rebuilt on a scale that would dwarf even Rome or Constantinople. The new Luoyang was designed as a grid of perfection. The "Palace City" sat in the center-north, the "Inner City" housed the officials, and the "Outer City" contained the markets and the masses.

But a city of a million people—which Luoyang quickly became—is a hungry beast. The immediate hinterlands could not feed such a population, especially one swollen with non-producing courtiers, soldiers, and Buddhist monks. (By the end of the dynasty, Luoyang boasted over 1,300 Buddhist temples, including the towering Yongning Pagoda, a wooden skyscraper said to be 136 meters tall).

The Tai Cang was the solution. It was the terminal point of a massive logistical network that drew grain from the fertile fields of Hebei, Shandong, and Henan. It was the battery that powered the Emperor’s dream. Without the Tai Cang, Xiaowen’s Sinicization would have ended in starvation and revolt. The granary was the anchor that allowed the nomadic Tuoba to finally settle down.

Part III: The Architecture of the Equal Field

How did the Northern Wei fill 168 massive pits with millet? The answer lies in an economic revolution known as the Equal Field System (Juntian Zhi).

Before the Northern Wei, land ownership in the north was chaotic. Warlords and powerful aristocratic families hoarded vast estates, turning free peasants into serfs and hiding them from the tax collectors. The state was starving while the rich got fatter.

In 485 AD, at the urging of the Empress Dowager Feng (Xiaowen’s regent and grandmother), the state issued a decree: All land belongs to the Emperor.

The government then redistributed the land to the peasantry. Every able-bodied man was given a set amount of land (roughly 40 mu for crop growing) and a smaller plot for mulberry trees (for silk production). In exchange, the peasant owed the state three things:

- Zu (Grain Tax): A fixed amount of millet.

- Diao (Textile Tax): A fixed length of silk or hemp cloth.

- Yong (Labor Tax): 20 days of service to the state per year.

The Tai Cang was the recipient of the Zu.

Imagine the scene in the autumn of 496 AD. The harvest is in. All across the Central Plains, carts creak under the weight of millet sacks. The roads to Luoyang are choked with dust and oxen.

Farmers from the surrounding commanderies arrive at the collection points. State officials, dressed in the flowing Han-style robes mandated by Emperor Xiaowen, inspect the grain. They plunge bamboo probes into the sacks, checking for rot, for sand mixed in to cheat the weight, for pests.

The grain is measured using the standard dou and sheng measures—bronze vessels cast by the imperial mint to ensure uniformity. (Archaeologists often find these measures in granary sites, the tools of the bureaucrat's trade).

Once accepted, the grain is transported to the Tai Cang. This was a high-security zone. The "Great Granary" was likely surrounded by its own walls and guarded by elite troops. Stealing imperial grain was a capital offense.

Laborers—perhaps peasants fulfilling their Yong labor tax—heave the sacks to the edge of the pits. The millet is poured in, a golden cascade disappearing into the dark earth. As the pit fills, workers might descend to stomp it down, compacting it to remove air pockets that could harbor beetles.

When a pit was full, it was sealed. A layer of reed mats, then clay, then perhaps a mound of earth to shed rain. A wooden marker or stone tablet would be placed on top, recording the date, the origin of the grain, and the official responsible.

This system was more than just taxation; it was social engineering. The Equal Field System broke the power of the local warlords and created a direct link between the peasant and the Emperor. The peasant fed the Emperor, and the Emperor (through the Tai Cang) promised to feed the peasant in times of disaster.

The Tai Cang, therefore, was the physical bank vault of the Equal Field System. It proved that the system worked.

Part IV: The Granary at War

While the Tai Cang served a benevolent purpose in famine relief, its primary function was martial. The Northern Wei was a state perpetually at war. To the north, the Rouran nomads threatened the frontier. To the south, the Chinese Southern Dynasties (the Qi and later the Liang) were constant rivals for legitimacy.

An army marches on its stomach, and the Northern Wei army was massive. Cavalry requires not just grain for men, but vast amounts of fodder for horses. A single warhorse can consume ten times the grain of a human. The Tuoba cavalry, the iron fist of the dynasty, was a logistical nightmare.

The Tai Cang was the strategic hub for these campaigns. When Emperor Xiaowen launched his southern expeditions, the grain from these pits was loaded onto barges on the Luo River, which flowed into the Yellow River, and from there to the Grand Canal networks that were beginning to take shape.

The discovery of the Tai Cang in the eastern part of the palace complex is significant. It places the granary near the transport networks of the Luo River, facilitating the rapid movement of supplies.

In 503 AD, during the reign of Emperor Xuanwu (Xiaowen's successor), the Northern Wei launched a massive offensive against the Southern Liang. Hundreds of thousands of troops were mobilized. The Tai Cang would have been a hive of activity, with columns of grain carts exiting the gates day and night, fueling the war machine that pushed the Wei borders all the way to the Huai River.

In this context, the 168 pits were not just silos; they were the ammunition dumps of the ancient world.

Part V: The Grid and the City

The Tai Cang cannot be viewed in isolation from the city of Luoyang itself. The "Grid" of the granary mirrored the grid of the city, which was the most cosmopolitan place on earth at the time.

Northern Wei Luoyang was a city of startling contrasts. It was a city of devout Buddhism, where the chants of monks from the 1,300 temples mingled with the cries of merchants from Persia, Sogdia, and India. The markets of Luoyang were flooded with goods from the Silk Road: glassware from Rome (Daqin), silver from Sassanid Persia, and jade from Khotan.

The Tai Cang stood as the silent, stoic guarantor of this opulence. While the courtiers in the Palace City debated Buddhist sutras and drank wine from glass goblets, the granary ensured that the basic caloric needs of the metropolis were met.

The location of the granary—east of the Palace—is also symbolic. In Chinese cosmology, the East is associated with spring, growth, and wood. It is the direction of life. Placing the grain reserve in the east aligned with the feng shui of renewal and sustenance.

However, the city was also a pressure cooker. The forced Sinicization had alienated the conservative Xianbei military elites who remained in the northern garrisons. They saw Luoyang as a sinkhole of decadence, where soft, Chinese-speaking courtiers grew fat on the grain that they—the warriors—had secured.

The Tai Cang, filled with the taxes of the peasantry, became a symbol of this disparity. It was feeding the capital, but the soldiers on the frontier were going hungry.

Part VI: The Fire and the Fall

The glory of Northern Wei Luoyang was brief—a supernova that burned bright and died violently.

In 523 AD, the Rebellion of the Six Garrisons erupted. The northern frontier troops, furious at their neglect and the "softness" of the Luoyang court, rose up. The rebellion tore the empire apart.

By 528 AD, the warlord Erzhu Rong—a brutal general from the north—marched on Luoyang. He captured the Dowager Empress Hu and the young emperor, and in a horrific act known as the Incident at Heyin, he slaughtered over 2,000 court officials, throwing their bodies into the Yellow River.

The city of Luoyang was sacked. The magnificent Yongning Pagoda was struck by lightning and burned to the ground in 534 AD, a fire that reportedly lasted for three months.

What happened to the Tai Cang during these cataclysms?

Archaeology provides a somber clue. The granaries of this era were often the first targets of rebels and invading armies. If you control the food, you control the city. If you cannot hold the city, you burn the food.

While the current excavation reports do not explicitly detail a layer of ash in every pit, the abandonment of the site coincides with the violent end of the Northern Wei. In 534 AD, the empire split into Eastern and Western Wei. The capital was moved to Ye and Chang'an, respectively.

Luoyang was abandoned. The bustling metropolis, which had housed over half a million people, became a ghost town. The Tai Cang was left to the elements. The wooden superstructures rotted away. The pits, perhaps emptied by looting soldiers or desperate refugees, slowly filled with the silts of the flooding Luo River.

The grid was buried. The "Great Granary" was forgotten, sleeping beneath the wheat fields of the Tang, Song, Ming, and Qing dynasties, until the 21st century.

Part VII: The Echo in the Earth

The unearthing of the Tai Cang is a major milestone in Chinese archaeology, rivaling the discovery of the Hanjia Granary (Sui/Tang dynasty) in the 1970s.

The Hanjia Granary, also in Luoyang, is famous for its carbonized grain—blackened, fossilized millet that was found still inside the pits. The Tai Cang predates Hanjia by over a century. It is the grandfather of the imperial storage system.

The discovery validates the descriptions in the Weishu. It proves that the Northern Wei possessed a state capacity that rivaled the Roman Empire at its height. The ability to extract, transport, and store 20,000 tonnes of grain requires a level of bureaucratic sophistication—mathematics, record-keeping, standardization—that dispels the old notion of the "Barbarian" dynasties as chaotic interludes between the Han and the Tang.

The Tai Cang shows us that the Northern Wei were not just warriors; they were master builders and administrators. They laid the groundwork for the reunification of China. The systems they refined—the Equal Field, the militia system, the centralized granaries—were inherited by the Sui and Tang dynasties.

When we look at the grid of the Tai Cang, we are looking at the blueprint of the Golden Age of China.

Conclusion: The Empty Silos

Today, the Tai Cang pits are empty. The millet that once fed the armies of Xiaowen is long gone, turned to dust or eaten by the ancestors of the people who now live in modern Luoyang.

But the emptiness is profound. Standing at the edge of one of these 11-meter wide abysses, one feels the weight of history. You can almost hear the creak of the ox-carts, the shout of the tax inspectors, the rustle of the dry grain pouring like water.

The Tai Cang Grid is a monument to the fundamental truth of civilization: before there can be art, before there can be philosophy, before there can be emperors or armies, there must be bread. Or, in the case of the Northern Wei, there must be millet.

The Tuoba clan rode out of the steppe and realized that to build an empire, they had to stop moving. They had to dig. And in digging these pits, they planted the seeds of a legacy that would outlast their stone steles and their wooden pagodas. They built a bank vault for the harvest, a fortress against hunger, and in doing so, they etched their ambition into the very geology of China. The Tai Cang has been unearthed, and with it, the undeniable grandeur of a dynasty that bridged the worlds of the nomad and the farmer.

Reference:

- https://english.news.cn/20260119/c776fe6e332846cbac354df679c82bac/c.html

- https://en.people.cn/n3/2026/0119/c90000-20416163.html

- https://www.weareiowa.com/article/news/local/plea-agreement-reached-in-des-moines-murder-trial/524-3069d9d4-6f9b-4039-b884-1d2146bd744f?y-news-28229594-2026-01-16-caxino-chronicles-significant-discovery-north-wei-national-granary-luoyang

- https://news.az/news/ancient-northern-wei-imperial-granary-found-in-luoyang

- https://www.weareiowa.com/article/news/local/plea-agreement-reached-in-des-moines-murder-trial/524-3069d9d4-6f9b-4039-b884-1d2146bd744f?y-news-28227418-2026-01-16-fezbet-celebrates-archaelogical-discovery-of-northern-wei-national-granary-at-luoyang-site

- https://ca.okfn.org/index.html%3Fp=16.html?y-news-28227418-2026-01-16-fezbet-celebrates-archaelogical-discovery-of-northern-wei-national-granary-at-luoyang-site

- https://www.j.u-tokyo.ac.jp/coelaw/COESOFTLAW-2005-5.pdf

- https://www.straitstimes.com/paid-press-releases/luoyangs-historical-legacy-where-ancient-art-meets-modern-innovation-20250522

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/cambridge-history-of-china/northern-economy/628CBB089FD8B642C7DB5858D5F6E1BF

- http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Division/beiwei-econ.html

- https://www.weareiowa.com/article/news/local/plea-agreement-reached-in-des-moines-murder-trial/524-3069d9d4-6f9b-4039-b884-1d2146bd744f?y-news-28227448-2026-01-16-betfair-reports-breakthrough-with-discovery-of-northern-wei-national-granary-at-luoyang-site

- http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Tang/tang-econ.html