The ocean has a memory. It remembers the cities it has swallowed, the forests it has drowned, and the voices it has silenced. For thousands of years, the people of Brittany—that rugged, wind-battered peninsula on the western edge of France—have told stories of a golden city lost beneath the waves. They call it Ys. They tell of King Gradlon and his wild daughter Dahut, of golden gates and a stolen key, and of a catastrophic flood that punished a sinful civilization.

For centuries, scholars dismissed Ys as a fairy tale, a Celtic variation of the Atlantis myth designed to teach Christian morality. But the ocean, it seems, has finally decided to speak.

In a groundbreaking discovery that has sent shockwaves through the archaeological world, researchers have found a 7,000-year-old stone wall submerged off the coast of Brittany. It is not a natural formation. It is a massive, engineered structure, built by human hands at a time when history tells us only "primitive" hunter-gatherers roamed the land. This discovery does not just rewrite the history of Stone Age Europe; it whispers a terrifying possibility: The legends are true.

This is the story of the Atlantis of Brittany.

Part I: The Ghost in the Sonar

The discovery did not begin with a treasure map, but with a glitch in the data.

In 2017,

Yves Fouquet, a geologist with the French research institute Ifremer, was scanning the seabed off the Île de Sein, a tiny, treeless island perched at the treacherous tip of the Pointe du Raz. This area is known to sailors as one of the most dangerous stretches of water in Europe. The currents here rip through the rocky channels with violent force, capable of crushing modern vessels, let alone ancient ones.Fouquet was studying the bathymetry—the underwater topography—of the region using high-resolution multibeam sonar. As the colorful 3D maps materialized on his screen, stripping away the blue veil of the Atlantic, something caught his eye.

Nature, generally, hates straight lines. Underwater landscapes are chaotic: jagged reefs, rolling sandbanks, scattered boulders. But there, on the screen, was a line. A perfect, deliberate line.

It was a ridge, about 120 meters (nearly 400 feet) long, sitting at a depth of 9 meters (30 feet). It didn't meander like a submerged riverbed or crumble like a rockfall. It cut across a submerged terrace with the stubborn geometry of human will.

"It looked like a wall," Fouquet would later tell reporters. "But at that depth, it shouldn't exist."

For five years, the data sat, a tantalizing anomaly. It wasn't until 2022 that a team of divers and archaeologists, led by

Yvan Pailler of the University of Western Brittany (UBO) and the CNRS (French National Centre for Scientific Research), finally descended into the cold, green gloom to touch the ghost.The Dive into Deep Time

Diving off the coast of Brittany is not like diving in the Caribbean. The water is cold, the visibility is often poor, and the currents are a constant physical assault. The team had to wait for the slack tide—the brief, quiet window between the ocean's inhalation and exhalation—to safely inspect the site.

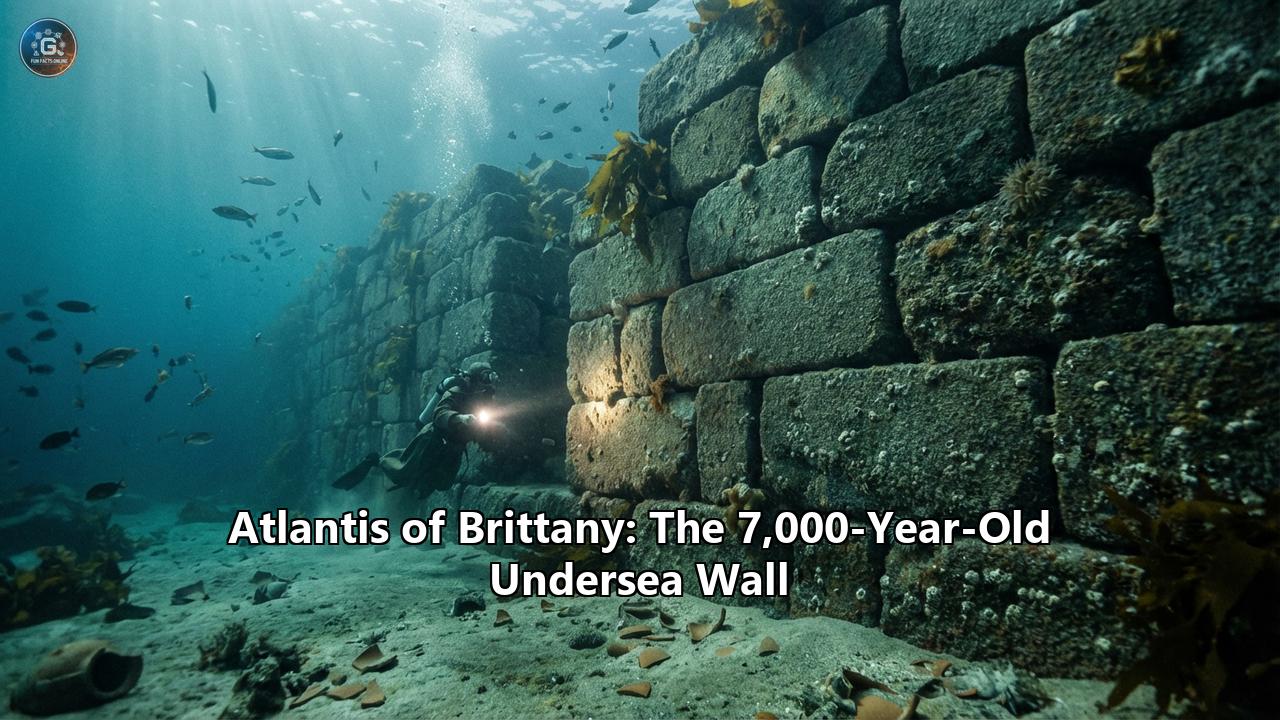

When they reached the bottom, the sonar's promise was fulfilled in stone.

Looming out of the murky twilight was a

megalithic wall. It was built from large granite blocks, some weighing several tons. But it wasn't just a pile of rocks. It was architectural.As the divers swam along its length, their flashlights cutting through the gloom, they realized they were looking at something that defied the standard timeline of history. This wasn't a Roman ruin or a Medieval pier. The depth of the water and the geological history of the region meant this wall had to be

much older.Radio-carbon dating and sea-level analysis confirmed the impossible. This structure was built between 5800 and 5300 BC.

That is 7,000 years ago.

To put that in perspective:

- It is 2,500 years older than the Great Pyramid of Giza.

- It is 500 years older than the famous standing stones of Carnac, just a few miles down the coast.

- It was built when mammoths were recently extinct, and humanity was supposedly just figuring out how to plant seeds.

This was the work of a sophisticated, organized, and powerful society—a society that lived on a coast that no longer exists.

Part II: The Drowned World of the Mesolithic

To understand why this wall is so shocking, we have to travel back in time. We have to strip away the water and look at Brittany as it was in 5500 BC.

This was the

Mesolithic-Neolithic transition*, a pivotal moment in human history. The Ice Age was over, but its shadow still lingered. The massive glaciers that had once crushed northern Europe were melting, and the global sea level was rising.But it hadn't risen

fully yet.In 5500 BC, the map of Europe looked different. Britain was likely just becoming an island, separated from the mainland by a rising channel. The coast of Brittany extended kilometers further out into the Atlantic than it does today. The Île de Sein was not an island, but a granite hill overlooking a vast, lush coastal plain.

This was a paradise. The plain was covered in forests of oak, elm, and hazel. Rivers meandered through grassy marshes, teeming with waterfowl. The forests were alive with red deer, roe deer, and wild boar. And the sea—the rising, encroaching sea—was exploding with life: seals, salmon, shellfish, and whales.

The People of the Shells

Archaeologists call the people who lived here the Téviec and Hoëdic cultures, named after two small islands where their spectacular cemeteries were found.

For a long time, we thought of Mesolithic people as simple nomads—small bands of hunter-gatherers scraping by, moving constantly to survive. The underwater wall shatters that image. You don't build a 120-meter-long, 3,000-ton granite wall if you are a nomad. You build it because you are staying.

The discovery suggests these people were sedentary hunter-gatherers. They were masters of their environment. They didn't need to farm because the ocean provided a harvest more bountiful than any wheat field.

Isotope analysis of bones from the era reveals their diet was rich in marine protein. They were people of the tide. They ate seals, seabirds, and massive quantities of fish. They wore jewelry made of intricate cowrie shells. They buried their dead in elaborate stone-lined graves, crowned with antlers of red deer, sprinkling them with red ochre—a symbol of blood and life.

But their life was not just peaceful fishing. The graves at Téviec tell a darker story. Some of the skeletons found there—including two women buried together under a roof of antlers—show signs of extreme violence. One had an arrowhead embedded in her spine. Another had suffered multiple blows to the head.

This was a violent, crowded, complex world. As the sea rose, it pushed people inland, compressing territories. The wall off the Île de Sein may have been born from this tension.

What Was the Wall?

Why build a massive wall on the beach? Archaeologists have two main theories, and both are fascinating.

Theory 1: The Ultimate Fish TrapIn a world before supermarkets, catching fish was life. The wall might have been part of a massive tidal fish weir. The builders would have constructed the stone wall to create a barrier. At high tide, fish would swim over the wall or through gaps to feed in the shallow lagoon behind it.

As the tide receded, the water would rush out, but the fish would be trapped behind the stone barrier (perhaps aided by wooden wicker fences or nets strung between the monoliths).

This would have been an industrial-scale food engine, capable of feeding hundreds of people. It required communal effort to build and maintain—proof of a complex social hierarchy.

Theory 2: The First SeawallThis is the more haunting theory.

The sea was rising. The elders of the tribe would have remembered a time when the beach was miles away. The younger generation would have seen the high tide creeping closer to their village every year. Storms would have become more destructive, the surges swallowing the land.

Was this wall a desperate attempt to hold back the ocean?

Was it a dyke, built to protect a freshwater lagoon or a settlement from the saltwater that was slowly poisoning their world? If so, it is a monument to a losing battle. It represents the first time humans tried to fight climate change with engineering.

And they lost.

*Part III: The Legend of Ys – The Echo of Trauma

“Voulc'h a-barz er ger a Is? (Do you hear the bells of Ys?)” — Old Breton saying.The science tells us that 7,000 years ago, a sophisticated culture in Brittany was slowly drowned by the rising sea, forcing them to abandon their stone monuments and retreat inland.

The folklore tells us exactly the same thing.

There is no legend in Brittany more famous, or more tragic, than that of Ker-Ys, the City of Lowlands. It is a story that has been told around peat fires for over a thousand years. When you read the legend alongside the archaeological report, the parallels are spine-chilling.

The Story of the Golden City

According to the myth, Ys was the most beautiful city in the world. It was built on the coast of Cornouaille (southwestern Brittany), in the Bay of Douarnenez—just a few miles from where the underwater wall was found.

The city was built below sea level. To protect it, the King, Gradlon the Great, constructed a massive dyke—a golden wall that encircled the city. The only way in or out was through a single great gate.

Gradlon possessed the only key to this gate, a silver key that he wore on a chain around his neck at all times.

Ys was a marvel of wealth and commerce. Its ships traded with the furthest corners of the earth. But wealth brought corruption. The citizens of Ys turned away from the old gods (or the new Christian God, depending on the version) and embraced debauchery.

At the center of this decadence was Princess Dahut, King Gradlon's daughter.

Dahut is one of the most complex figures in Celtic mythology. In Christian retellings, she is a villain—a sorceress, a sinner, a woman who took a new lover every night and had him killed by morning. But in older, pagan echoes of the story, she is a priestess of the sea, a guardian of the old ways who refused to bow to the encroaching new religion.

She loved the ocean. She felt that the dyke separated the city from its true source of power.

One night, a mysterious stranger arrived in Ys. He was dressed in red (often interpreted as the Devil, or a Red Knight). He seduced Dahut, whispering to her of the freedom of the waves. He convinced her that the gate should be opened, just a crack, to let the love of the ocean in.

While her father slept, Dahut crept into his chamber. She gently lifted the silver key from around his neck.

She went to the great sea gate. She turned the key.

The Deluge

It was not a gentle opening. The Atlantic Ocean, held back for so long by human arrogance, roared in like a ravenous beast. The dyke collapsed. A wall of black water, higher than the tallest tower, crashed into the city.

King Gradlon was awakened by Saint Gwenolé (a local holy man), who shouted,

"Flee, King! The wrath of God is upon us!"Gradlon mounted his magical horse, Morvarc'h (Sea Horse), and galloped toward the higher ground, with Dahut clinging to his waist.

But the water was faster. The waves nipped at the horse's hooves. The animal struggled, weighed down by the double burden. The ocean was claiming its due.

Saint Gwenolé rode up beside them and screamed,

"Throw the demon down! The ocean wants her, not you!"In the most heartbreaking moment of Breton mythology, Gradlon looked at his daughter. He looked at the drowning city. And he pushed her off.

Dahut fell into the boiling surf. Immediately, the waves calmed. The ocean was satisfied. Dahut did not die, however; she was transformed into a Morgane (a mermaid), destined to haunt the waves forever, singing of her lost city.

Gradlon reached the safety of the shore at Douarnenez. He looked back, but Ys was gone. Only the tips of the spires remained for a moment before vanishing into the grey Atlantic.

Part IV: When Myth Meets Science

For centuries, the story of Ys was treated as a metaphor. It was a sermon on the dangers of lust and the inevitability of divine punishment.

But the discovery of the

Sein Island Wall changes the conversation.We now have physical proof of:

This is not a coincidence. This is what experts call

Geomythology—the preservation of real geological events in oral tradition.The Trauma of the "Transgression"

The period when the wall was built (5800–5300 BC) coincides with the end of the

Flandrian Transgression*. This was the rapid rise in sea levels following the last Ice Age.For the people of the Mesolithic, the end of the world was not a sudden explosion; it was a slow, relentless drowning.

Imagine you are a child in 5000 BC. Your grandfather takes you to the beach and points to a reef a mile offshore. "When I was a boy," he says, "that was a forest. We hunted deer there."

By the time you are an old man, the water is lapping at the foundations of your own house. The massive wall your ancestors built to trap fish or hold back the tide is now submerged, useless. The "monoliths" that marked your territory are disappearing under the waves.

This loss would have been traumatic. It would have shattered their worldview.

Why is the ocean eating our land? Did we offend the spirits?These questions would have been codified into stories. The "sin" of Ys is just a later rationalization for the "punishment" of the flood. The "dyke" of King Gradlon is a folk memory of the actual stone barriers (like the one just discovered) that their ancestors built to try and stop the water.

Dahut, the princess who "opened the gate," is the personification of the breach—the moment the ocean finally won.

The "Atlantis" of the North

This phenomenon isn't unique to Brittany. All along the Atlantic façade of Europe, there are stories of drowned lands.

- Cornwall (Lyonesse): Just across the channel, the Cornish tell of the Kingdom of Lyonesse, a rich land that connected Land's End to the Scilly Isles, swallowed by the sea in a single night.

- Wales (Cantre'r Gwaelod): The "Sunken Hundred." A legendary kingdom protected by dykes. The keeper of the sluice gates, Seithenyn, got drunk and forgot to close them, drowning the land. (Sound familiar?)

- Doggerland: We now know a vast landmass connected Britain to Europe. It drowned around 6000 BC. While no specific "city" legend survives, the trauma of its loss is likely baked into the collective psyche of Northern Europe.

The Sein Wall is the first time we have touched the

hardware of these myths. We have found the actual stones laid by the people who inspired the stories.Part V: The Time Capsule

Today, the wall sits in 9 meters of water. It is a haven for marine life. Crabs scuttle over the granite blocks that human hands shaped 7,000 years ago. Seaweed waves from the monoliths like the hair of the drowned Princess Dahut.

The site is difficult to visit. The currents around the Île de Sein are ferocious, and the weather is unpredictable. It is a protected archaeological zone, guarded by the very ocean that destroyed it.

But its significance cannot be overstated.

Conclusion: The Bells Still Ring

There is a local legend in Brittany that says the City of Ys is not dead, only sleeping. It is said that on calm nights, you can still hear the bells of the cathedral ringing beneath the waves. The prophecy says that

"Pa vo beuzet Paris, Ec'h adsavo Ker Is" ("When Paris is swallowed, Ys will rise again").We may not have found a cathedral of gold. But we have found something even more precious. We have found the truth.

The 7,000-year-old wall of Brittany is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit. It is the footprint of a lost civilization that refused to go quietly into the dark water. It is the real Atlantis. And thanks to the work of modern science, it has finally risen.

* (Note to Reader: This discovery is part of ongoing research by the SAMM (Société d'Archéologie et de Mémoire Maritime) and the CNRS. As divers continue to map the "Sentinels of the Deep," who knows what other secrets are waiting in the silence of the Atlantic?)*Reference:

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/europe/opens-up-new-prospects-ancient-underwater-wall-discovered-off-french-coast-hints-at-coastal-societies/articleshow/125947030.cms

- https://journals.openedition.org/geomorphologie/10386

- https://www.discovermagazine.com/prehistoric-underwater-wall-hints-at-sophisticated-human-engineering-7-000-years-ago-48404

- https://www.labrujulaverde.com/en/2025/12/the-oldest-and-deepest-stone-structures-in-europe-built-by-hunter-gatherers-7900-years-ago-found-submerged-off-the-coast-of-brittany/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%C3%A9viec

- https://www.ancient-origins.net/history/makeshift-casket-sea-shells-and-antlers-6500-year-old-grave-unfortunate-ladies-t-viec-007705

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388508368_Holocene_paleoenvironmental_reconstructions_in_western_Brittany_Bay_of_Brest_Part_II_-_A_7_kyr_human-environment_story_with_a_focus_on_the_Neolithic-Bronze_Age_transition

- https://bcd.bzh/becedia/en/the-mesolithic-necropolis-of-teviec