The Arabian Peninsula, today a vast expanse of hyper-arid deserts and shifting sand dunes, was once a verdant paradise. Where the scorching sun now beats down on the An-Nafud and Rub’ al Khali, lush savannahs once swayed in the breeze, fed by monsoonal rains and dotted with permanent lakes. This is the lost world of "Green Arabia," a dramatic climatic anomaly that persisted for thousands of years, allowing Neolithic human populations to thrive in the heart of the desert.

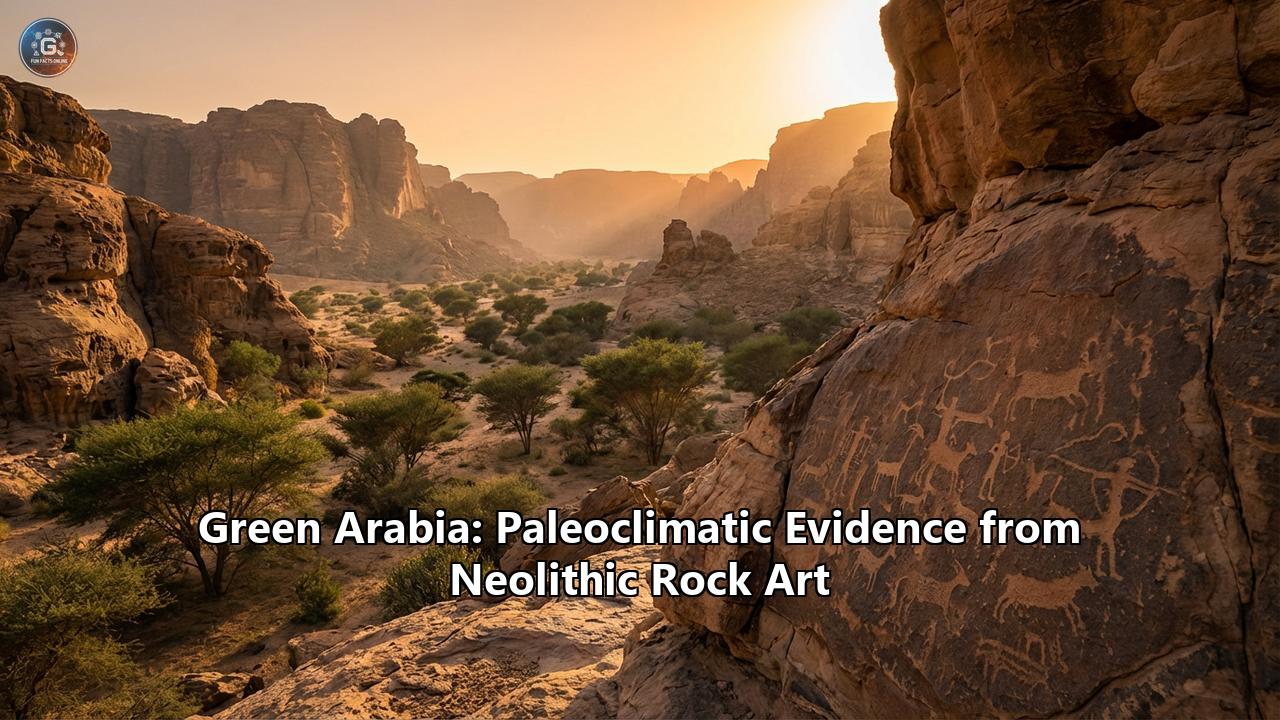

The most compelling evidence for this lost Eden does not come from textbooks, but from the rocks themselves. Carved into the sandstone escarpments of Saudi Arabia are thousands of intricate petroglyphs—ancient messages in stone that depict a landscape teeming with life. From life-sized camels to hunting scenes involving lions and leopards, these images serve as a paleoclimatic archive, freezing a wet and vibrant moment in time that vanished millennia ago.

The 2025 Breakthrough: Giants of the Nefud

In late 2025, the archaeological world was shaken by a monumental discovery in the southern Nefud Desert. At sites like Jebel Arnaan, Jebel Misma, and Jebel Mleiha, researchers uncovered a series of rock art panels that fundamentally rewrote the timeline of human habitation in the region. These were not the crude sketches of passing nomads, but monumental, life-sized reliefs of camels and wild equids, carved with astonishing realism and depth.

Dating back approximately 12,000 years to the Pleistocene-Holocene transition, these carvings predate the well-known Neolithic pastoral scenes. They depict wild camels—ancestors of the domesticated dromedary—in their winter coats, with detailed fur textures and biological features that suggest the artists had intimate, year-round knowledge of these animals. The sheer scale of the artwork, with some figures measuring up to three meters in length, implies a society with the surplus time and resources to create "monumental" public art, a hallmark of a stable and thriving culture.

Crucially, these carvings were found near ancient dry lake beds, or playas. Sediment analysis confirmed that during the time these artists were at work, these depressions were filled with water, creating seasonal oases that supported not just the camels, but a diverse ecosystem of grazers and predators.

The Holocene Humid Phase: A Window of Life

The "Green Arabia" phenomenon was driven by a northward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and the Indian Ocean Monsoon. Between roughly 10,000 and 6,000 years ago, this shift brought heavy, regular rainfall to the Arabian interior. This period, known as the Holocene Humid Phase, transformed the desert into a mosaic of grasslands, river networks, and freshwater lakes.

The geological evidence is incontrovertible. Ancient lake beds at Jubbah and Mundafan contain fossilized remains of freshwater snails, reeds, and even fish. Deep inside caves like Hoti in Oman and the recently analyzed Dahul Al-Summan system near Riyadh, stalagmites (speleothems) have grown in layers that act like tree rings, recording pulses of rainfall that span millions of years. These mineral archives confirm that the "Green Arabia" of the Neolithic was not a fluke, but part of a cyclical climate pattern that has occurred repeatedly over the last 8 million years.

Reading the Rocks: Fauna of a Lost Savannah

The rock art of Saudi Arabia acts as a biological inventory of this humid period. By analyzing the species depicted, archaeologists can reconstruct the environment with remarkable precision.

1. The Water Buffalo and Aurochs:Perhaps the most startling evidence comes from sites like Musayqirah (Graffiti Rocks) near Riyadh, where carvings clearly depict the Bubalus—the wild water buffalo. Unlike camels or gazelles, water buffalo are physiologically incapable of surviving in arid environments. They require daily access to water and wallowing mud. Their presence in the rock art of central Arabia is a "smoking gun" for a wet climate with permanent water sources. Similarly, depictions of the Aurochs (wild cattle) suggest ample grazing lands, as these massive bovines needed vast quantities of grass to survive.

2. The Predators:A healthy population of large herbivores supports a hierarchy of predators. The rock art at Shuwaymis and Jubbah is replete with dynamic scenes of lions, leopards, and hyenas. In one famous panel at Shuwaymis, a lion is shown attacking a wild donkey, a scene that could easily belong on the Serengeti plains of today. The presence of these apex predators confirms a biomass richness that the current desert ecosystem could never support.

3. The Hunters and Their Dogs:Human figures in these panels are often shown hunting with bows and arrows, accompanied by packs of dogs. In fact, the rock art at Shuwaymis and Jubbah contains some of the earliest evidence of dog domestication in the world. These dogs are depicted with leashes, assisting in the hunt of ibex and gazelle. The "Jubbah style" of human figures—elongated, with distinct clothing and hairstyles—suggests a distinct cultural identity that flourished alongside these animals.

Key Sites of the Neolithic Revolution

Two sites in the Hail region of Saudi Arabia stand out as the crown jewels of this prehistoric archive and have been recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Jubbah (Jebel Umm Sanman):Once an island in a vast paleolake, Jebel Umm Sanman ("Two Camel Hump Mountain") overlooks the modern town of Jubbah. The rock faces here are a palimpsest of thousands of years of history. The Neolithic carvings are characterized by their size and detail, often depicting cattle with distinct horn shapes and markings. As the lake began to dry up around 6,000 years ago, the art style changed, becoming more schematic and focusing more on camels—creatures of the encroaching desert—rather than the cattle of the vanishing savannah.

Shuwaymis (Jabal Al-Manjor and Jabal Raat):Located in a remote area of volcanic lava fields and sandstone escarpments, Shuwaymis remained undiscovered by modern science until 2001. Its isolation preserved it perfectly. The site is famous for its incredibly long panels of carvings that follow the course of an ancient wadi (river valley). Here, the density of predator depictions is higher, and the hunting scenes are visceral and chaotic. The "Lion of Shuwaymis" panel is a masterpiece of Neolithic art, capturing the tension and violence of the natural world.

The Great Desiccation

Around 6,000 years ago, the monsoons retreated south. The lakes of Jubbah and Mundafan evaporated, leaving behind salt flats. The grasslands withered, and the great herds of aurochs and water buffalo vanished, either dying out or migrating to the few remaining river valleys in Mesopotamia and the Levant.

The rock art records this tragedy. Later panels from the Bronze Age and Iron Age (Thamudic period) show a shift in focus. The naturalistic, life-sized animals are replaced by smaller, stylized stick figures. The diverse menagerie of the savannah is replaced almost exclusively by the camel—the "ship of the desert"—essential for survival in the new, harsh reality. The "Green Arabia" was gone, but its memory was etched into the stone, waiting for the shifting sands to reveal it once more.

Implications for Human History

The discovery of Green Arabia challenges the traditional narrative of human migration. Rather than a barrier to be avoided, the Arabian Peninsula was a lush corridor connecting Africa to Eurasia. The stone tools found associated with the rock art—distinct from those in the Levant or Africa—suggest that Arabia was not just a highway, but a destination; a place where unique Neolithic cultures developed, innovated, and thrived for millennia before the desert reclaimed their home.

Today, as we stand before the "monumental" camels of Jebel Misma or the hunting lions of Shuwaymis, we are not just looking at art. We are looking at data—irrefutable, beautiful proof that the Earth's climate is a dynamic, ever-changing force, and that the deserts of today were the gardens of yesterday.

Reference:

- https://saudi-archaeology.com/sites/jubbah/

- https://www.bna.bh/En/SaudiArabiasancientcavestudyrevealsgreenpastspanningeightmillionyears.aspx?cms=q8FmFJgiscL2fwIzON1%2BDjYUoXCYzJJ3RbfFUvmuRZ8%3D

- https://archaeologymag.com/2025/10/ancient-life-size-rock-art-in-saudi-arabia/

- https://www.aramcolife.com/en/publications/the-arabian-sun/articles/2021/week-14/jubbah-art-rock

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251546572_Holocene_and_Pleistocene_pluvial_periods_in_Yemen_southern_Arabia

- https://saudipedia.com/en/article/1427/history/landmarks-and-monuments/rock-art-in-hail-province

- https://www.iflscience.com/ancient-rock-art-reveals-arabia-was-once-home-to-some-unexpected-animals-45984