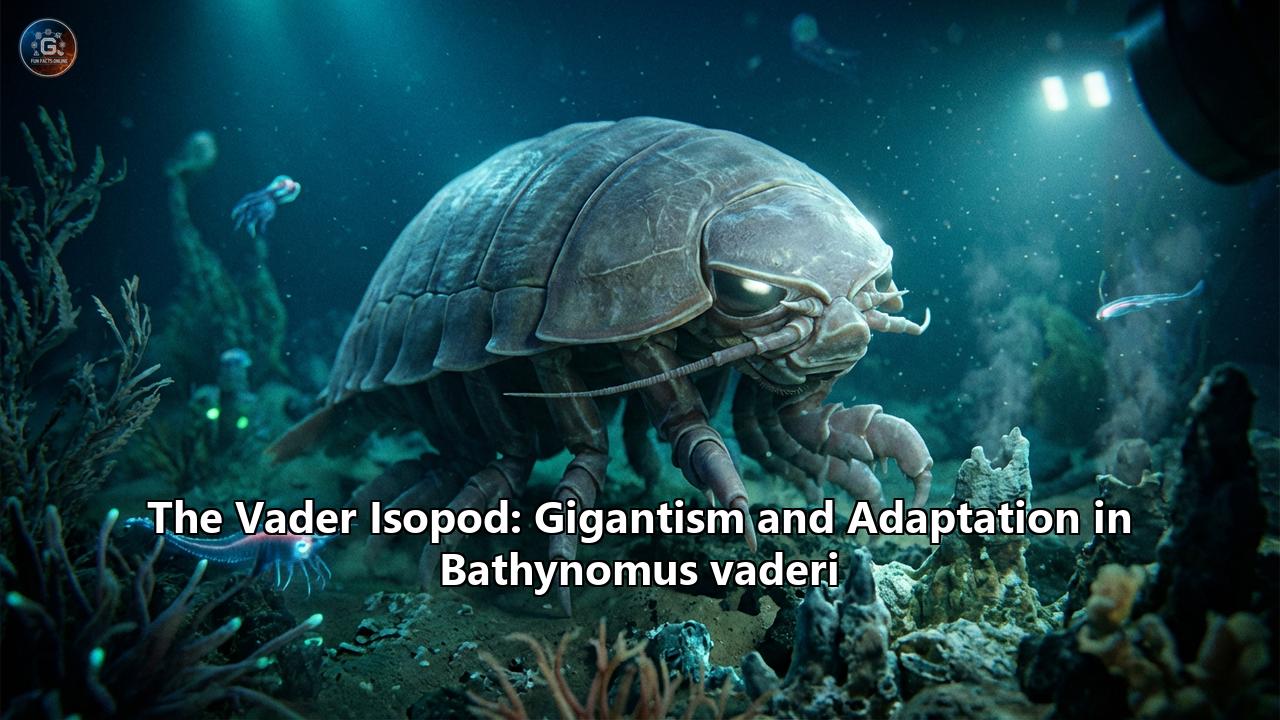

In the eternal twilight of the bathypelagic zone, where the pressure is crushing and the temperature hovers near freezing, a silhouette moves across the silt. It is an armored giant, a creature of segmented plating and ancient design, scavenging the ocean floor with the silent determination of a machine. For millions of years, this lineage has existed in the dark, unseen and unnamed by human tongues. But in early 2025, a team of scientists pulled this leviathan from the depths of the South China Sea and saw something familiar in its visage. They looked upon its broad, helmet-like cephalon and saw not just a crustacean, but an icon of pop culture villainy. They named it Bathynomus vaderi.

The "Vader Isopod" is more than just a biological novelty with a catchy name; it is a "supergiant" testament to the power of evolutionary adaptation. Discovered off the coast of Vietnam near the Spratly Islands, Bathynomus vaderi represents a significant addition to the genus Bathynomus, a group of isopods that have fascinated marine biologists since their first discovery in the 19th century. Reaching lengths of over 30 centimeters (12 inches) and weighing more than a kilogram, this creature is a titan among its kind, dwarfing the common garden pillbugs to which it is distantly related.

The discovery of B. vaderi highlights a golden age of deep-sea exploration, where technology allows us to peer into the planet's last frontiers. But it also comes at a time of strange paradoxes. While scientists marvel at its genomic adaptations and evolutionary history, the very same creature has found itself the center of a culinary craze in Southeast Asia, grilled and served as a high-end delicacy. Simultaneously, its habitat in the South China Sea is the stage for intense geopolitical tension and environmental degradation, raising urgent questions about the conservation of species we are only just beginning to understand.

This article delves into the world of the Vader Isopod, exploring the science of deep-sea gigantism, the genetic secrets of survival in the abyss, the creature’s ancient evolutionary lineage, and the complex relationship it now shares with the human world—from the laboratory to the dinner plate.

II. The Discovery: A New Face in the AbyssThe story of Bathynomus vaderi begins not on a high-tech research vessel, but in the bustling chaos of a Vietnamese port. For years, fishermen operating deep-sea trawlers in the South China Sea had been hauling up massive, armored "sea bugs" (known locally as bọ biển). These creatures were largely considered bycatch, strange curiosities from the deep that were occasionally sold for a pittance or discarded. However, as the global appetite for exotic seafood expanded, these isopods began appearing more frequently in markets in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.

It was amidst this commercial trade that science caught up with commerce. A team of researchers from the National University of Singapore (NUS), the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), and the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology recognized that the "giant isopods" being sold were not all the same. While Bathynomus jamesi and Bathynomus kensleyi were known to inhabit the region, some specimens stood out.

In 2023, the team, led by renowned carcinologist Peter Ng, began a detailed morphological examination of specimens collected near the Spratly Islands. They noticed distinct features that set these individuals apart from known species. The most striking characteristic was the shape of the cephalon (head) and the anterior margin. It possessed a high, arching structure and specific biological contours that gave it a hooded, helmeted appearance.

When the team looked at the specimen head-on, the resemblance was undeniable. The sloping, armored head shield, the large, reflective compound eyes, and the grim, mandibles created a visage eerily reminiscent of Darth Vader’s mask. In the taxonomy of biology, names are often descriptive (like giganteus) or honorific (like jamesi), but occasionally, they are cultural. The team embraced the resemblance, and in their paper published in the journal ZooKeys in January 2025, they officially christened the species Bathynomus vaderi.

Taxonomic DistinctionMorphologically, B. vaderi is distinguished by more than just its sci-fi resemblance. It belongs to the "supergiant" group of the genus. In the world of Bathynomus, size matters for classification. "Giants" are generally considered adults between 8 and 15 centimeters. "Supergiants" are those massive adults that exceed 17 centimeters, often growing well past 30 centimeters.

B. vaderi is differentiated from its closest relative, Bathynomus jamesi, by several subtle but crucial anatomical features:- The Cephalic Ridge: B. vaderi possesses a unique bony ridge protruding from its coracoid bone, a feature absent in other supergiants.

- Hip Bone Depression: There is a pronounced depression in the hip bone (coxa) of the pereopods (legs), which serves as a diagnostic marker.

- Upwardly Curved Spines: The pleotelson (tail armor) features upwardly curved caudal spines, a defensive adaptation that gives the tail a serrated, weaponized look.

These physical traits are not merely aesthetic; they are the result of millions of years of fine-tuning to a life of scavenging in the soft, silty bottom of the bathypelagic zone.

III. The Phenomenon of Deep-Sea GigantismTo understand Bathynomus vaderi, one must understand the biological rule-breaking environment it calls home. The most common question asked when people see a foot-long isopod is: Why are they so big?

This phenomenon is known as abyssal gigantism or deep-sea gigantism. It is observed across various taxa—from the colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni) to the Japanese spider crab (Macrocheira kaempferi) and the seven-armed octopus (Haliphron atlanticus). For isopods, the contrast is stark. Their terrestrial cousins, the woodlice (pillbugs), rarely exceed a centimeter in length. B. vaderi is over 20 times their size.

Several converging theories explain this massive growth:

1. Kleiber’s Rule and Metabolic EfficiencyKleiber's Law states that an animal's metabolic rate scales to the ¾ power of its mass. In the deep sea, food is scarce. The environment is oligotrophic, meaning nutrient levels are low. A larger body size confers a metabolic advantage. Larger animals have a lower metabolic rate per unit of mass compared to smaller ones. This allows B. vaderi to operate on a highly efficient energy budget. It can swim for longer distances in search of food and survive longer periods of starvation—a critical adaptation when your next meal might be a whale carcass that falls once every decade.

2. Bergmann’s Rule and TemperatureBergmann’s rule, originally formulated for warm-blooded animals, observes that populations of larger size are found in colder environments. While isopods are ectotherms (cold-blooded), a similar principle applies. The near-freezing temperatures of the deep ocean (typically 4°C or 39°F) slow down cell proliferation and metabolism. This slow life history allows for continuous, indeterminate growth. Unlike many terrestrial animals that stop growing upon reaching maturity, deep-sea crustaceans often continue to grow throughout their extended lifespans. B. vaderi does not live fast and die young; it lives slowly and grows massively.

3. The Cell Size HypothesisResearch into deep-sea crustaceans suggests that their large size is not just due to having more cells, but having larger cells. Low temperature increases blood viscosity and makes oxygen transport more difficult. Larger cells have a more favorable surface-area-to-volume ratio for certain metabolic processes in cold environments. Furthermore, in the high-oxygen environment of cold deep water, gigantism is less constrained by respiratory limits.

4. Ecological ReleaseIn the shallow waters, a slow-moving, foot-long crustacean would be an easy snack for large predatory fish, sharks, and marine mammals. The deep sea, however, has lower predation pressure. While predators exist, they are fewer and farther between. This "ecological release" allows the isopod to grow to sizes that would be evolutionarily suicidal in the reef zones above. The heavy armor of B. vaderi is likely sufficient defense against many of the smaller, energy-conserving predators of the abyss.

IV. Genomic Giants: Secrets in the DNAThe physical adaptations of Bathynomus vaderi are mirrored by equally impressive genetic adaptations. While the specific genome of B. vaderi is still being analyzed following its 2025 discovery, we can draw direct inferences from the fully sequenced genome of its "sister" supergiant, Bathynomus jamesi.

In 2022, a groundbreaking study led by the Chinese Academy of Sciences sequenced the B. jamesi genome, revealing the largest genome of any crustacean sequenced to date—approximately 5.89 Gigabases. It is highly probable that B. vaderi shares these genomic characteristics.

The "Jumping Genes" of Stress AdaptationThe supergiant isopod genome is riddled with transposable elements (TEs), often called "jumping genes." These are sequences of DNA that can move around the genome. In B. jamesi, TEs make up a staggering 84% of the genome. Why so much "junk" DNA? Scientists believe this is an evolutionary toolkit. The proliferation of TEs promotes genetic plasticity. It allows the genome to change more rapidly, potentially helping the organism adapt to the extreme stressors of the deep sea—crushing pressure (up to 100 atmospheres), darkness, and hypoxia.

Hormonal Control of GigantismThe genome analysis also identified expanded gene families related to thyroid and insulin hormone signaling pathways. In other animals, these pathways are critical regulators of growth and body size. The expansion of these specific genes in Bathynomus suggests a genetic "foot on the gas" pedal for growth. The metabolic pathways are tuned for lipid (fat) accumulation. B. vaderi is essentially a biological battery; its body is packed with lipid reserves, stored in a specialized "fat body" distributed throughout its tissues. This inefficient lipid degradation is a feature, not a bug—it allows the animal to hoard energy from a single meal to fuel its massive body for years.

V. Habitat and Ecology: The South China Sea Abyss Bathynomus vaderi has, so far, been exclusively identified in the deep waters surrounding the Spratly Islands and the broader South China Sea basin. To understand its life, we must visualize its home.The South China Sea is a marginal sea with a deep oceanic basin that plunges to depths of over 5,000 meters. The Spratly Islands are the tips of submerged mountains and reefs, but surrounding them are abyssal plains and continental slopes where B. vaderi roams. This region is a "marine snow" biome.

The Scavenger’s Role B. vaderi is a facultative scavenger. Its primary food source is marine snow—the ceaseless shower of organic detritus (dead plankton, fecal pellets, decaying matter) falling from the productive sunlit waters above. However, its massive size requires more substantial bonanzas.The Vader Isopod is a "necrophage," a specialist in eating the dead. They are the vultures of the deep. Their sensory adaptations are tuned for this specific purpose.

- Chemoreception: They possess two pairs of antennae. The shorter pair is chemosensory, capable of detecting the chemical plume of a decaying carcass from miles away in the currentless dark.

- Vision: Despite the total darkness, they have enormous, triangular compound eyes with a reflective tapetum lucidum (similar to a cat's eye). This suggests they may utilize bioluminescence—either to spot glowing prey or to recognize conspecifics.

The defining event in the life of a Bathynomus vaderi is a "whale fall." When a cetacean dies and sinks to the bottom, it creates a temporary ecosystem. Bathynomus are among the first responders. They are "gorgers." Their physiology is adapted to eat catastrophic amounts of food in a single sitting.

A B. vaderi can distend its stomach to fill almost its entire body cavity. It will eat until it is physically unable to move, anchoring itself to the carcass with its hooked legs. Once full, it may enter a state of semi-torpor, digesting its meal for months or even years. In captivity, giant isopods have famously survived for over five years without a single meal, a testament to their metabolic efficiency.

Predation and DefenseWhile they are the eaters of the dead, they must also avoid becoming the dead. Their primary defense is their exoskeleton. The overlapping, calcified segments allow them to roll up into a ball (volvation), similar to a pillbug, protecting their softer, ventral underbelly. This "Vader helmet" is not just for show; it is a shield. Their upwardly curved tail spines (uropods) also serve to make them difficult to swallow for deep-sea fish like gulper eels or sleeper sharks.

VI. Evolutionary Odyssey: A Living Fossil?To look at Bathynomus vaderi is to look back in time. The order Isopoda dates back to the Carboniferous period, some 300 million years ago. This was a time before the dinosaurs, when the earth was covered in swamp forests and the seas were ruled by primitive sharks and ammonites.

The genus Bathynomus itself has a fossil record stretching back to the Mesozoic, approximately 160 million years ago. Fossils found in Japan and the Americas show Bathynomus species that look remarkably similar to the modern B. vaderi. This morphological stability has earned them the moniker "living fossils."

The Shallow-to-Deep MigrationEvolutionary biologists have long debated the origins of deep-sea fauna. Did they evolve in the deep, or did they migrate there? The evidence for isopods points to a "polar submergence" or general shallow-water origin. The ancestors of B. vaderi likely lived in shallow, coastal waters.

As competition in the shallow seas increased—perhaps with the rise of modern predatory bony fish—these ancestors were pushed into deeper, colder, and darker waters. This transition likely occurred in high-latitude (polar) regions where the temperature difference between shallow and deep water is minimal (isothermal water columns). Over eons, they adapted to the pressure, lost their pigmentation (though B. vaderi retains a pale lilac/pink hue), and gained their immense size.

The existence of B. vaderi in the South China Sea supports the theory of widespread dispersion of these "supergiants" across the Indo-Pacific basins, isolated by underwater topography that allows for speciation—one lineage becoming jamesi, another kensleyi, and in the isolated deep basins off Vietnam, vaderi.

VII. From the Deep Sea to the Dining TableIn a twist of fate that Darth Vader himself might find ironic, the "Vader Isopod" has become a sought-after commodity not for its scientific value, but for its taste.

Since around 2017, a culinary trend has emerged in Vietnam, Taiwan, and parts of Japan for consuming giant isopods. In Vietnam, they are marketed as "bọ biển" (sea bugs) or "dragons of the sea." The discovery of B. vaderi was essentially a retroactive one; the species had been served on plates in Quy Nhon, Da Nang, and Hanoi for years before scientists gave it a name.

The Culinary ExperienceRestaurants specializing in exotic seafood display live B. vaderi in tanks, often highlighting their "alien" appearance to attract adventurous diners and social media influencers. The creatures are typically prepared by steaming or grilling.

- The Taste: Gastronomes describe the meat as resembling lobster or crab, but with a unique texture. It is sweeter than shrimp but denser, often compared to monkfish. The taste is reportedly intense, a concentration of the deep ocean's briny essence.

- The Price: Due to the difficulty of trawling at depths of 500+ meters, B. vaderi is expensive. A single large specimen can fetch prices upwards of $50 to $100 USD in high-end Hanoi seafood markets.

The visual shock value of the isopod—legs, armor, and "Vader" face intact—has made it a viral sensation on platforms like TikTok and Instagram. Diners often pose with the steamed creature, its pale purple shell glistening, before cracking it open. This commercialization has shifted the status of the isopod from "trash fish" to "luxury product."

However, this popularity raises ethical and health concerns. As scavengers, isopods can bioaccumulate heavy metals (like cadmium and mercury) found in the deep-sea sediment. Furthermore, their digestive tracts often contain whatever fell to the ocean floor, including plastics. A study of Bathynomus in other regions found significant amounts of microplastics in their stomachs, a grim reminder of human pollution reaching the deepest places on Earth.

VIII. Conservation and the Future of the AbyssThe formal description of Bathynomus vaderi comes with a warning. The South China Sea is one of the most contested and ecologically stressed bodies of water on the planet.

The Threat of TrawlingThe primary method for catching B. vaderi is bottom trawling. This fishing method involves dragging heavy weighted nets across the sea floor. It is indiscriminate and destructive. It plows through the benthic sediment, destroying the delicate habitats of deep-sea corals, sponges, and other slow-growing organisms.

While B. vaderi is not currently listed as endangered (mostly due to being "Data Deficient"), its biological traits make it highly vulnerable.

- Low Fecundity: Deep-sea giants reproduce slowly. Females brood their eggs in a marsupium (pouch) for months. They produce relatively few offspring compared to shallow-water crustaceans.

- Slow Growth: It takes years, perhaps decades, for a supergiant isopod to reach reproductive maturity.

Removing large adults from the population for the seafood trade could lead to a rapid collapse of the stock, similar to the "boom and bust" cycles seen in other deep-sea fisheries like the Orange Roughy.

Habitat DestructionBeyond fishing, the South China Sea is undergoing massive physical alteration. The construction of artificial islands and dredging for military infrastructure destroys reefs and alters sedimentation patterns. While B. vaderi lives deeper than most of this construction, the cascading effects of sedimentation and pollution affect the entire water column.

Furthermore, the prospect of deep-sea mining for polymetallic nodules poses a future threat. The extraction of these minerals from the seabed would obliterate the benthic layer where B. vaderi lives, creating sediment plumes that could choke their gills and bury their food sources.

The Call for Sustainable ManagementThe researchers who discovered B. vaderi—Ng, Sidabalok, and their colleagues—emphasize the "urgent need" to understand deep-sea biodiversity before it is lost. The fact that a 30cm predator went undescribed until 2025 is a humbling reminder of our ignorance. They argue for better regulation of deep-sea fisheries, the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) in the deep basins, and more research into the baseline population health of these unique animals.

IX. Conclusion: The Face Behind the Mask Bathynomus vaderi is a creature of dualities. It is a monster of the abyss and a marvel of evolution. It is a scavenger of the dead and a feeder of the living. It is a scientific triumph and a commercial commodity.Naming it after Darth Vader was a stroke of genius, not just for the physical resemblance, but for the thematic resonance. Like the Star Wars villain, the isopod is armored, mysterious, and dwells in the "dark side" of the biosphere. But unlike the Sith Lord, B. vaderi is not a villain. It is a vital component of the planetary ecosystem, a recycler of energy that keeps the deep ocean functioning.

As we stare into the compound eyes of the Vader Isopod, we are staring into a mirror of our own making. We see our pop culture reflected in its name, our consumption reflected in its fate, and our scientific curiosity reflected in its discovery. The challenge now is to ensure that this "Dark Lord of the Deep" continues to reign in its abyssal kingdom, rather than becoming just another ghost in the fossil record.

The discovery of Bathynomus vaderi is not the end of the story; it is the opening crawl of a new chapter in our exploration of the final frontier on Earth. And as any good story tells us, there is always more lurking in the dark, waiting to be found.

Reference:

- https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/giant-sea-bug-species-discovered-in-vietnam-named-after-darth-vader

- https://www.reddit.com/r/food/comments/1mwg92r/i_ate_bathynomus_giganteus_with_fried_and_spring/

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/researchers-identified-a-new-supergiant-crustacean-with-14-legs-and-they-named-it-after-darth-vader-180985900/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301894457_New_Fossil_Record_of_the_Genus_Bathynomus_Crustacea_Isopoda_Cirolanidae_from_the_Middle_and_Upper_Miocene_of_Central_Japan_with_Description_of_a_New_Supergiant_Species

- https://ipdefenseforum.com/2025/03/china-primary-cause-of-marine-habitat-damage-in-south-china-sea-report-says/

- https://hakaimagazine.com/news/how-giant-isopods-got-supersized/

- https://scispace.com/pdf/the-deep-sea-isopods-a-biogeographic-and-phylogenetic-1o55ypmvgt.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233367849_The_deep-sea_isopods_A_biogeographic_and_phylogenetic_overview

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9107163/

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2026/jan/06/squid-argentina-coast-guard-overfishing-ecosystems-animal-cruelty-human-rights-china

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isopoda

- https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/darth-vader-giant-isopod-sold-widely-as-seafood-raises-concerns-about-overfishing

- https://www.orfonline.org/research/in-deep-water-current-threats-to-the-marine-ecology-of-the-south-china-sea

- https://features.csis.org/environmental-threats-to-the-south-china-sea/

- https://news.mongabay.com/2024/04/island-building-and-overfishing-wreak-destruction-of-south-china-sea-reefs/