The subatomic world is rarely quiet, but few particles have caused as much noise in the halls of modern physics as the muon. For decades, this unstable, heavy cousin of the electron has been at the center of a scientific mystery that threatens—or promises—to unravel our understanding of the universe. This is the story of the Muon $g-2$ (pronounced "g minus two") anomalies, a saga involving a giant superconducting magnet traveling across land and sea, billions of particle decays, supercomputers pushing the limits of calculation, and a stubborn numerical discrepancy that refuses to die.

As we stand in early 2026, following the release of the final results from the Fermilab experiment, we find ourselves at a precipice. The measurement is more precise than ever, yet the theoretical ground beneath it has shifted, leading to a crisis not just of measurement, but of meaning. Are we seeing the footprints of "New Physics"—dark matter particles, supersymmetry, or ghost-like bosons? Or are we witnessing a subtle breakdown in our ability to calculate the behavior of the Standard Model itself?

To understand the stakes, we must journey into the heart of the quantum vacuum, where "empty" space is actually a boiling cauldron of virtual particles, and see how the muon uses this vacuum as a dance floor, wobbling in a magnetic field to a rhythm that might just be slightly off-beat.

Part I: The Heavy Electron and the Quantum Wobble

"Who Ordered That?"

The story begins not with a magnet, but with a question of necessity. In the 1930s, physicists thought they had the building blocks of matter figured out: protons, neutrons, and electrons. The electron was the carrier of charge, the lightweight workhorse of electricity. Then, in 1936, Carl Anderson and Seth Neddermeyer discovered a track in their cloud chamber that didn't fit. It looked like an electron, behaved like an electron, but it was over 200 times heavier.

Nobel laureate Isidor Isaac Rabi famously quipped, "Who ordered that?"

This particle was the muon ($\mu$). It belongs to the second generation of matter, a heavier replica of the first. It is unstable, decaying into an electron and neutrinos in about 2.2 microseconds—a lifetime that, while short to us, is an eternity in the particle world. Because it is charged and has spin (intrinsic angular momentum), the muon acts like a tiny bar magnet. It has a north pole and a south pole.

The strength of this internal magnet is defined by a quantity known as the magnetic moment, often denoted by $\mu$ (not to be confused with the particle name). The relationship between the particle’s magnetic moment, its charge, its mass, and its spin is encapsulated in a dimensionless number called the g-factor.

Dirac’s Prediction and the "2"

In 1928, Paul Dirac formulated the equation that combined quantum mechanics with special relativity. The Dirac equation predicted that for a point-like fermion (like an electron or muon), the g-factor should be exactly 2.

If the universe were simple, $g$ would equal 2, and the story would end there. But in the quantum universe, nothing is simple.

The Anomalous Moment

The "2" in Dirac’s equation assumes the particle is alone in the universe. But in Quantum Electrodynamics (QED), a particle is never alone. As a muon travels through space, it is surrounded by a cloud of "virtual particles" that pop in and out of existence. The muon emits a photon and re-absorbs it; it emits a photon that splits into an electron-positron pair which then annihilates.

These fleeting interactions modify the muon’s properties. They slightly alter how the muon responds to an external magnetic field. Instead of $g=2$, the value is $g = 2(1+a)$, where $a$ is the "anomalous magnetic moment."

Hence, the quantity of interest is:

$$ a_\mu = \frac{g-2}{2} $$

This is the "g minus two." It represents the deviation from Dirac’s classical prediction, caused entirely by the quantum fluctuations of the vacuum. Measuring $a_\mu$ is essentially measuring the vacuum of the universe itself. If the vacuum contains only the particles we know (Standard Model), we get one number. If the vacuum contains hidden monsters—Dark Matter particles, Supersymmetric partners—they will bump into the muon, subtly changing the value of $g-2$.

The muon is the perfect candidate for this probe. The electron is too light; the influence of heavy virtual particles scales with the mass of the probe squared ($m^2$). The muon, being 207 times heavier than the electron, is roughly 43,000 times more sensitive to New Physics. The tau particle is even heavier, but it decays too quickly to be stored in a ring. The muon is the "Goldilocks" particle: heavy enough to feel the unknown, but long-lived enough to be measured.

Part II: The Standard Model Calculation

To claim we found "New Physics," we must first know exactly what the "Old Physics" predicts. The Standard Model prediction for $a_\mu$ is a tapestry woven from three fundamental forces: Electromagnetism (QED), the Weak Force, and the Strong Force (QCD).

1. QED: The Triumph of Perturbation Theory

The electromagnetic contribution is the largest and most precise. It involves the muon exchanging photons and leptons. Julian Schwinger calculated the first correction (the "one-loop" term) in 1948, famously finding it to be $\alpha / 2\pi \approx 0.00116$. Today, theorists have calculated these diagrams up to the fifth order (involving over 12,000 Feynman diagrams). The QED prediction is known to an astounding precision of 1 part in a billion. There is no controversy here.

2. Electroweak: The Heavy Bosons

The contribution from the Weak force involves the exchange of massive $W$, $Z$, and Higgs bosons. Since these particles are heavy, their effect is small, but calculable. This part of the pie is also well-understood.

3. The Hadronic Headache

Here lies the dragon. The Strong Force (QCD) contributions involve quarks and gluons. Unlike QED, we cannot use simple perturbation theory because the strong force is, well, strong. At low energies (where the muon lives), quarks are confined inside hadrons (protons, pions, etc.).

There are two main hadronic components:

- Hadronic Vacuum Polarization (HVP): A photon emitted by the muon turns into a "blob" of hadrons (like a pion pair) before being reabsorbed. This is the biggest source of uncertainty.

- Hadronic Light-by-Light (HLbL): A more complex dance where three photons interact with a loop of hadrons.

Because we cannot calculate HVP easily from first principles (the equations are too hard), physicists historically used a "Data-Driven" approach. They looked at experimental data from particle colliders where electrons and positrons annihilate into hadrons ($e^+e^- \to \text{hadrons}$). By using a mathematical trick called the dispersion relation, they could convert that cross-section data into the HVP contribution for the muon.

This reliance on other experimental data (the "R-ratio") would become the crux of the crisis in the 2020s.

Part III: The Experimental Saga

The quest to measure $g-2$ has been a generational relay race, with the baton passed from CERN to Brookhaven to Fermilab.

CERN (1960s-1970s)

CERN pioneered the storage ring technique. They realized that if you accelerate muons to a specific "magic momentum" (about 3.1 GeV/c), the electric fields used to focus the beam would not disturb the spin measurement. The final CERN experiment confirmed the theory to 7 parts per million (ppm). It was a triumph, but the cracks were not yet visible.

Brookhaven E821 (1997-2001)

In the 1990s, Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) in New York built a superconducting storage ring 14 meters (50 feet) in diameter. The goal was to reach 0.35 ppm precision.

In 2001, BNL released a bombshell: their measurement was higher than the Standard Model prediction by about 3 to 4 standard deviations ($3-4\sigma$). In particle physics, $3\sigma$ is "evidence," while $5\sigma$ is "discovery." It was a tantalizing hint. Was it a statistical fluke? A systematic error? Or the first sign of Supersymmetry?

The BNL experiment ended in 2001 because funding ran out, leaving the physics community hanging from a cliff for two decades.

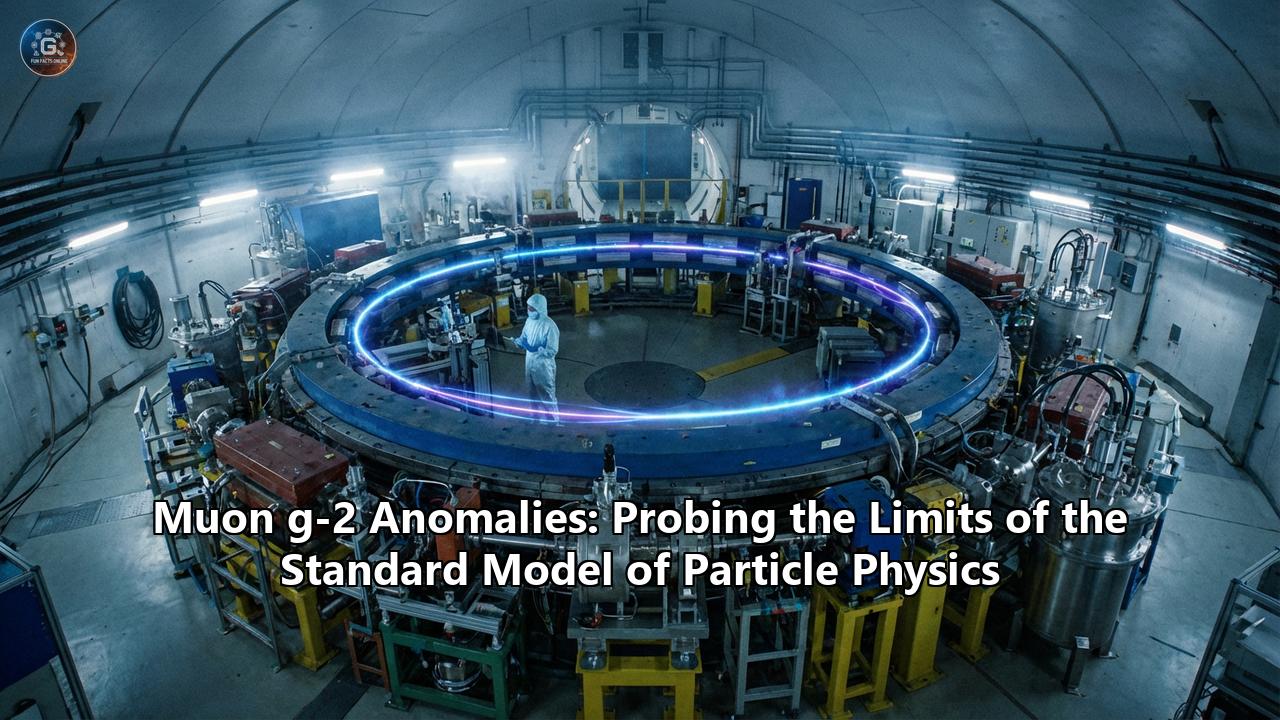

The Big Move (2013)

To check the BNL result, scientists needed a better experiment. Fermilab, near Chicago, had a powerful particle beam that could produce more muons. But building a new magnet of that quality would cost a fortune and take years. The BNL magnet was a masterpiece of engineering; the magnetic field was incredibly uniform.

So, they decided to move it.

In the summer of 2013, the 50-foot, 700-ton electromagnetic ring was lifted intact, placed on a barge, sailed down the East Coast, around Florida, up the Mississippi River to Illinois, and then driven on a specialized truck to Fermilab. It was a logistical opera. If the ring twisted by even a few millimeters, the superconducting coils would snap, and the experiment would be over before it began. It arrived safely.

Part IV: Inside Fermilab E989

The Fermilab experiment (E989) was designed to be a "BNL on steroids." The goal was to reduce the error bars by a factor of four, pushing the precision to 140 parts per billion (ppb).

The Life of a Muon at Fermilab

- Creation: It starts with protons slamming into a target, creating pions. The pions decay into muons.

- Selection: The beam is filtered to select only antimuons ($\mu^+$) with the "magic momentum" of 3.094 GeV/c.

- Injection: The muons enter the storage ring. A "kicker" magnet gives them a swift kick to push them onto a stable circular orbit.

- Storage: The muons circulate in a vacuum chamber, surrounded by the massive superconducting magnet generating a uniform 1.45 Tesla vertical field.

- Precession: As they circle, their internal spins rotate (precess). Because $g \neq 2$, the spin rotates slightly faster than the muon circles the ring. The spin axis drifts.

- Decay: When a muon decays, it emits a positron ($e^+$). The direction of the positron is correlated with the direction of the muon’s spin at the moment of death.

- Detection: 24 electromagnetic calorimeters line the inside of the ring. They detect the positrons and measure their energy and arrival time.

The Wiggle Plot

The raw data is a histogram of positron arrivals over time. Because the muon spin is rotating relative to the detector, the number of high-energy positrons detected oscillates. It goes up and down, carving out a sine wave that sits on top of an exponentially decaying curve (since the muons are dying off).

This is the "Wiggle Plot." The frequency of this wiggle ($\omega_a$) tells us the anomalous magnetic moment directly.

$$ \omega_a = a_\mu \frac{eB}{m} $$

To get $a_\mu$, you need to measure the frequency ($\omega_a$) and the magnetic field ($B$) with excruciating precision.

Blinding the Clock

To prevent "experimenter's bias"—the subconscious tendency to adjust analysis until the result matches the expectation—the Fermilab team used a "blinded" analysis. The master clock of the experiment was set to a secret frequency. A hardware module adjusted the clock ticks by a random offset known only to two people outside the collaboration (and sealed in an envelope).

For years, the physicists analyzed the data in "blinded units." They optimized their software, calculated their systematic errors, and argued over details, all without knowing the real answer. Only when the analysis was frozen did they hold an "unblinding" ceremony to reveal the true frequency.

Part V: The Result and the Theoretical Crisis

The Run 1 Result (2021)

On April 7, 2021, the world watched via Zoom (due to the pandemic) as the Fermilab team unveiled the result from their first run.

The number: $116,592,040(54) \times 10^{-11}$.

It matched the old Brookhaven result perfectly. When combined, the experimental average stood at $4.2\sigma$ away from the Standard Model prediction (based on the "2020 Theory Initiative White Paper"). The physics world exploded with excitement. The anomaly was real. The Standard Model was breaking.

The 2023 Update and the Final 2025 Release

The experiment continued. Runs 2 and 3 reduced the uncertainty further. Finally, in June 2025, the collaboration released the definitive analysis of the full dataset (Runs 1 through 6).

The precision achieved was 127 ppb, beating the design goal. The central value remained high, solidifying the experimental measurement.

If we compare this 2025 experimental number to the 2020 Theory White Paper, the discrepancy is over $5\sigma$. In any normal timeline, this would be a Nobel Prize-winning discovery of New Physics.

But this is not a normal timeline.

The Plot Twist: Lattice QCD and CMD-3

While the experimentalists were refining their machines, the theorists were having a civil war.

Recall that the Standard Model prediction relies on the Hadronic Vacuum Polarization (HVP).

- The Old Way (R-ratio): Uses data from $e^+e^-$ colliders (like KLOE in Italy and BaBar in the US). These experiments measured the cross-section of electron-positron annihilation into pions. They generally agreed with each other and predicted a low HVP value, which leads to the $5\sigma$ discrepancy.

- The New Way (Lattice QCD): Lattice QCD simulates the strong force on a supercomputer by dividing space-time into a grid. For decades, it was too imprecise to be useful for $g-2$. But in 2021, the BMW Collaboration (Budapest-Marseille-Wuppertal) published a stunning result in Nature. Their Lattice calculation claimed a precision below 1%.

To make matters worse, in 2023, a new experiment called CMD-3 at the Budker Institute in Novosibirsk, Russia, released their measurement of the $e^+e^-$ cross-section. Unlike previous experiments (CMD-2, KLOE), the CMD-3 data showed a higher cross-section.

- Old $e^+e^-$ data $\rightarrow$ Low HVP $\rightarrow$ Anomaly ($5\sigma$)!

- CMD-3 data $\rightarrow$ High HVP $\rightarrow$ No Anomaly!

- Lattice QCD (BMW) $\rightarrow$ High HVP $\rightarrow$ No Anomaly!

By 2026, the situation is a "theoretical purgatory." The experimental measurement of the muon is rock solid. But we don't know what to compare it to. The disagreement between the old $e^+e^-$ data and the new CMD-3 data is uncomfortably large (over 5 standard deviations in some energy regions). Until this experimental discrepancy in the input data is resolved, we cannot say for sure if the muon is breaking the Standard Model.

Part VI: The "Hybrid" Hope and Window Observables

Physicists are clever. Facing this deadlock, they developed a "Hybrid" approach.

The HVP contribution comes from different energy scales (distances). Lattice QCD is very good at short distances (high energy) and intermediate distances, but struggles with long distances (low energy) due to computational noise. The $e^+e^-$ data is very good at long distances.

The "Window" method isolates specific distance ranges.

- Intermediate Window: This is the battleground. Both Lattice and Data-driven methods should work well here.

- Results: The Lattice calculations for the "Intermediate Window" are incredibly precise and consistent across different groups (BMW, Mainz, RBC/UKQCD). They all predict a value higher than the old $e^+e^-$ data.

This strongly suggests that the old $e^+e^-$ data (KLOE, BaBar) might have subtle systematic errors that underestimated the hadronic contribution. If the Lattice view of the "Intermediate Window" is adopted, the significance of the Muon $g-2$ anomaly drops from a discovery-level $5\sigma$ to a mere $2\sigma$ curiosity.

As of 2026, the consensus is shifting. The "Anomaly" might not be a sign of New Physics particles, but rather a sign that we underestimated the complexity of the Strong Force in our earlier calculations.

Part VII: What If It Is New Physics?

Let us suspend the skepticism for a moment. Assume the old data was right, the Lattice is wrong, and the $5\sigma$ discrepancy is real. What could be causing it?

The beauty of the muon anomaly is that it is "model-independent." It just tells you something is there. Theorists have proposed a zoo of candidates:

1. Supersymmetry (SUSY)

The grand dame of New Physics. SUSY predicts that every particle has a heavier "superpartner." A "smuon" (super-muon) and a "neutralino" could circulate in the vacuum loop alongside the muon. If these particles have masses around 200-500 GeV, they would generate exactly the shift we see in $g-2$. However, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) has hunted for SUSY for 15 years and found nothing. The "SUSY parameter space" that fits $g-2$ is shrinking, but it's not dead yet.

2. The Dark Photon ($Z'$)

What if there is a "Dark Sector" of the universe that doesn't interact with light? A "Dark Photon" would be a force carrier for this dark sector. It could mix very slightly with the regular photon. If the muon interacts with this Dark Photon, it would push the $g-2$ value. This model is attractive because it explains Dark Matter and the anomaly simultaneously.

3. Leptoquarks

These are hypothetical particles that can turn a lepton (like a muon) into a quark. They act as a bridge between the two families of matter. A leptoquark loop could easily solve the $g-2$ puzzle. Interestingly, leptoquarks were also proposed to explain other anomalies seen in B-meson decays (the "flavor anomalies"), though some of those have faded recently.

4. Two-Higgs Doublet Models (2HDM)

The Standard Model has one Higgs field. Why not two? A second Higgs doublet adds new scalar bosons that would interact with the muon.

Part VIII: The Future - J-PARC and the Muon Collider

Science does not stop at a stalemate. While theorists fight over HVP, experimentalists are building the next check.

The J-PARC E34 Experiment

In Japan, at the J-PARC facility, a completely different experiment is under construction.

The Fermilab/BNL method uses the "magic momentum" (3.1 GeV) to cancel out electric field effects. This requires a large 14-meter ring.

The J-PARC team said, "What if we don't use the magic momentum?"

They plan to use ultra-cold muons. They will stop muons in a target, cool them down until they are almost stationary, and then re-accelerate them to a lower energy. Because the beam is so "cold" (low emittance), they don't need strong electric focusing fields. This allows them to use a much smaller magnet (only about 66 cm diameter) and a completely different storage technique.

If Fermilab and J-PARC agree, the experimental value is indisputable. If they disagree, we have a whole new problem. J-PARC is expected to start data taking around 2027.

The Muon Collider Dream

The technology developed for $g-2$—cooling muons, storing them, manipulating their spins—is the stepping stone to the ultimate dream machine: a Muon Collider.

Smashing muons is better than smashing protons (which are messy bags of quarks) and better than electrons (which lose energy via synchrotron radiation). A Muon Collider could reach 10 TeV energies in a compact footprint, potentially discovering the particles that the LHC missed. The $g-2$ anomaly, whether real or not, has revitalized the muon community, pushing the technology forward by decades.

Part IX: Conclusion - The Legacy of the Wobble

As we view the landscape in 2026, the Muon $g-2$ anomaly remains the most tantalizing "maybe" in physics.

The Fermilab experiment has performed a masterpiece of measurement, locking down the value of the muon's magnetic moment to 127 parts per billion. It is one of the most precise measurements in the history of humanity.

However, the "discovery" of New Physics is currently held hostage by the disagreement between Lattice QCD and data-driven theory.

- If the Lattice is right, the Standard Model survives, proving remarkably resilient yet again. The "anomaly" was just a calculation error in the difficult hadronic sector.

- If the Lattice is wrong, and the historical data holds, then the muon is indeed feeling the phantom touch of a hidden universe.

In either case, the result is profound. If it’s New Physics, we have opened a door to the Dark Sector. If it’s Standard Model, we have mastered the Strong Force to an unprecedented level of precision, validating our theory of the universe down to the decimal points.

The muon, that heavy, unstable, unwanted cousin, has proven to be the most faithful guide we have. It wobbles in the dark, and by measuring that wobble, we are slowly, painfully, but surely, mapping the invisible fabric of reality.

Detailed Technical Breakdown

(In the following sections, we will dive deeper into the specific mechanisms that allow for such precision, intended for the reader who wants to understand the "how" behind the "what".)1. The Magic Momentum

Why 3.094 GeV/c?

The equation for the spin precession frequency relative to the momentum ($\omega_a$) in the presence of both magnetic ($\vec{B}$) and electric ($\vec{E}$) fields is given by the Thomas-BMT equation:

$$ \vec{\omega}_a = -\frac{e}{m} \left[ a_\mu \vec{B} - \left( a_\mu - \frac{1}{\gamma^2 - 1} \right) \frac{\vec{\beta} \times \vec{E}}{c} \right] $$

The second term involves the electric field $\vec{E}$. In a storage ring, you must use electric fields (Quadrupoles) to keep the beam focused vertically; otherwise, the muons would drift up or down and hit the ceiling/floor.

However, we want to measure $a_\mu$ using only $\vec{B}$. We don't want to know $\vec{E}$ perfectly.

Notice the term in the parenthesis: $\left( a_\mu - \frac{1}{\gamma^2 - 1} \right)$.

If we choose the muon velocity $\gamma$ such that this term is zero, the electric field effect vanishes!

$$ a_\mu = \frac{1}{\gamma^2 - 1} \implies \gamma = \sqrt{1 + \frac{1}{a_\mu}} \approx 29.3 $$

This $\gamma$ corresponds to a momentum of $p = 3.094$ GeV/c. This is the "Magic Momentum." It allows the experiment to use strong electric focusing without ruining the magnetic measurement.

2. The Magnetic Field Shimming

The magnet at Fermilab had to be uniform to roughly 15 parts per million (ppm) before analysis corrections. To achieve this, the team used tiny pieces of iron and steel foils, some as thin as a human hair, placed at specific locations around the 45-meter circumference. This process, called "shimming," involved thousands of iterations.

During the experiment, a "trolley" filled with NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) probes broke the vacuum and traveled around the ring every few days to map the field. In between trolley runs, 378 fixed NMR probes monitored the drift. The result was a map of the magnetic field averaged over the muon distribution known to better than 70 parts per billion.

3. The Pile-up and Gain Stability

One of the biggest systematic errors is "pile-up." If two low-energy positrons hit the calorimeter at the exact same time, the detector sees them as one high-energy positron. This distorts the energy spectrum and the time distribution. The Fermilab team developed sophisticated algorithms to disentangle these pulses using the shape of the light signal in the crystals.

Furthermore, the gain of the photodetectors can change if a lot of particles hit them at once (like a camera flash blinding you for a second). A laser calibration system fired light pulses into the detectors to monitor their stability 24/7, ensuring the gain was constant to better than $10^{-4}$.

4. The Beam Dynamics Corrections

Even with the Magic Momentum, not every muon is exactly at 3.094 GeV/c. There is a spread. This means the electric field term isn't exactly zero for everyone. This is the "E-field correction."

Also, the muons don't travel in a perfect circle; they oscillate horizontally (betatron motion). This is the "Pitch correction."

These corrections are small (parts per billion), but when you are chasing 127 ppb precision, they are huge. The detailed tracking of the beam profile using straw trackers (gas-filled tubes that detect passing charged particles) allowed the physicists to calculate these corrections with high confidence.

The Human Element

We must not forget the human effort. The Fermilab Muon $g-2$ collaboration consists of nearly 200 scientists from 7 countries. Graduate students spent nights in the control room, fueled by coffee, watching the "wiggle" appear in real-time. Postdocs spent years writing code to align the detector stations by millimeters. Senior scientists bet their careers on the validity of the Blind Analysis.

The release of the 2025 result was the culmination of a 20-year journey that began when the BNL magnet was turned off in 2001. It is a testament to the persistence of curiosity. Whether the anomaly survives the theoretical reckoning or not, the experiment stands as a monument to precision.

Summary of the Current Status (2026 Snapshot)

| Quantity | Value / Status | Notes |

| :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Experimental $a_\mu$ | 0.001 165 920 705 | Precision: 0.127 ppm (Fermilab Final). |

| SM Prediction (R-ratio) | ~0.001 165 918 100 | Based on old $e^+e^-$ data. Tension: $>5\sigma$. |

| SM Prediction (Lattice) | ~0.001 165 920 000 | Based on BMW 2025. Tension: < 1.5$\sigma$ (Agreement). |

| The Discrepancy | Ambiguous | Depends on whether you trust $e^+e^-$ data or Lattice QCD. |

| Next Step | J-PARC E34 | Independent check with different systematics (~2027). |

| Theoretical Goal | Resolve HVP | Clarify the CMD-3 vs. Radiative Return data conflict. |

The muon continues to spin. The physicists continue to calculate. And the universe keeps its secrets, for now, hidden in the decimal points.

Reference:

- https://www.particlebites.com/?p=8972

- https://www.innovationnewsnetwork.com/muon-g-2-experiment-final-results-confirm-magnetic-anomaly-in-muons/58745/

- https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-Muon-G-2-anomaly-in-physics-and-why-should-you-care

- https://arxiv.org/html/2503.03364v1

- https://cerncourier.com/a/new-muon-g-2-result-bolsters-earlier-measurement-2/

- https://physicsworld.com/a/the-muons-magnetic-moment-exposes-a-huge-hole-in-the-standard-model-unless-it-doesnt/

- https://news.liverpool.ac.uk/2025/06/03/muon-g-2-announces-most-precise-measurement-of-the-magnetic-anomaly-of-the-muon/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360650805_Muon_g-2_BMW_calculation_of_the_hadronic_vacuum_polarization_contribution

- https://www.energy.gov/science/articles/muon-g-2-announces-most-precise-measurement-magnetic-anomaly-muon

- https://indico.in2p3.fr/event/33627/contributions/155007/

- https://physicsworld.com/a/muon-g-2-achieves-record-precision-but-theoretical-tensions-remain/

- https://muon-gm2-theory.illinois.edu/2023-status/

- https://g-2.kek.jp/overview/

- https://web.tdli.sjtu.edu.cn/kimsiang84/2025/07/14/final-results-from-the-muon-g-2-experiment-at-fermilab/

- https://indico.global/event/8004/contributions/72202/attachments/35340/65898/J-PARCMuong2_PPC2024_241014.pdf

- https://agenda.infn.it/event/35353/contributions/239268/attachments/125774/185763/MS_240924_gm2_RICAP24-compresso.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=huLvw-_qkgg

- https://indico.cern.ch/event/1370980/contributions/6372383/contribution.pdf

- https://agenda.infn.it/event/30580/contributions/172256/attachments/97156/134045/ogawa_fccp2022.pdf

- https://indico.global/event/15366/