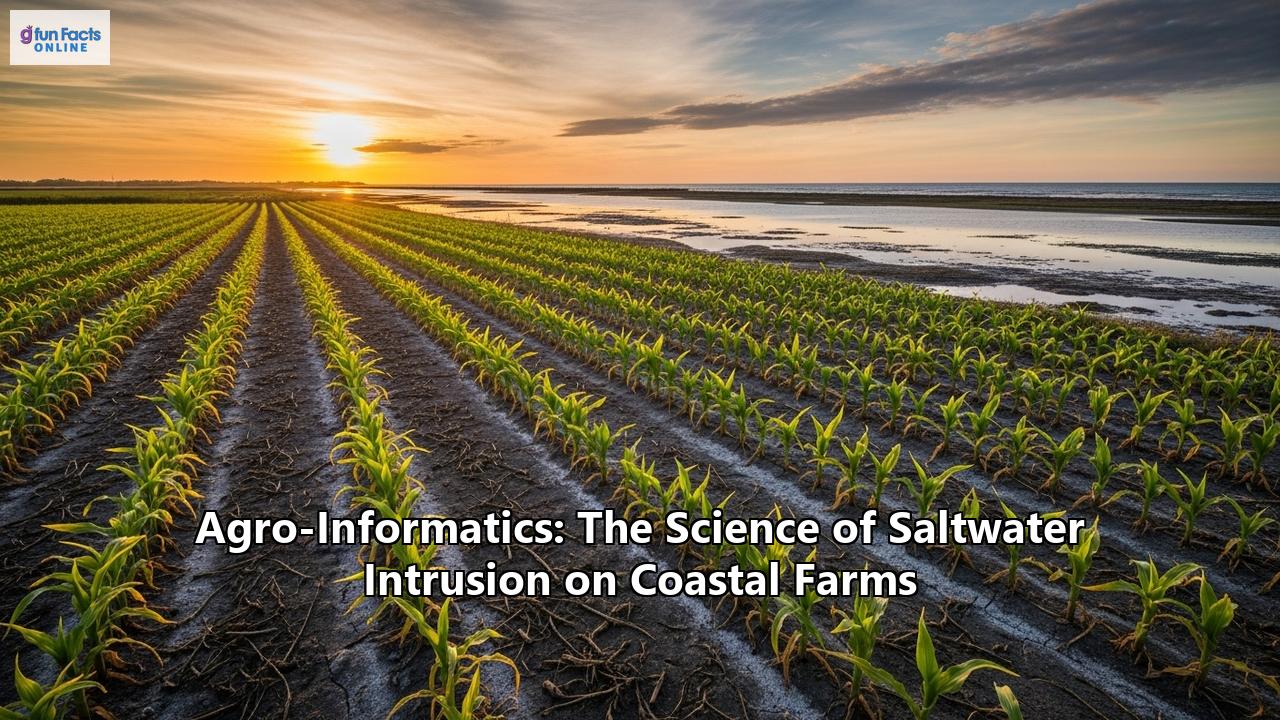

In the picturesque landscapes of coastal farms, a silent and often invisible threat is steadily advancing. This threat, known as saltwater intrusion, is the landward movement of seawater into freshwater aquifers and soils. It poses a significant and growing danger to global food security. As the planet grapples with the escalating impacts of climate change, rising sea levels, and increasing demand for freshwater, the problem of saltwater intrusion on coastal agricultural lands has become a critical area of concern.

Enter the burgeoning field of Agro-informatics, a powerful confluence of agriculture, information science, and technology. This interdisciplinary science is emerging as a crucial ally in the fight against saltwater intrusion. It offers innovative tools and data-driven strategies to monitor, predict, and mitigate its devastating effects. By harnessing the power of remote sensing, geographic information systems (GIS), sensor networks, big data analytics, and precision agriculture, agro-informatics is revolutionizing our understanding of this complex environmental challenge. It empowers farmers to build more resilient and sustainable coastal farming systems.

This comprehensive article delves into the intricate science of saltwater intrusion, exploring its causes and its profound impacts on coastal agriculture. It also examines the transformative role of agro-informatics in safeguarding these vital food-producing regions. We will journey through the technological innovations, the scientific breakthroughs, and the practical applications that are defining the future of coastal farming in a changing world.

The Creeping Tide: Understanding Saltwater Intrusion

Saltwater intrusion is a natural process that occurs in coastal areas where freshwater from rivers and underground aquifers meets the saltwater of the ocean. In a balanced system, the pressure of the freshwater flowing towards the sea keeps the denser saltwater at bay. However, this delicate equilibrium can be easily disrupted by a variety of factors, both natural and human-induced.

The Ghyben-Herzberg Relation: A Balancing ActThe fundamental principle governing the relationship between freshwater and saltwater in coastal aquifers is described by the Ghyben-Herzberg relation. This principle illustrates that for every unit of freshwater above sea level, there are approximately 40 units of freshwater below sea level in the aquifer. This is due to the density difference between freshwater and saltwater. When the freshwater table is lowered, the saltwater interface rises significantly, moving further inland.

Drivers of Saltwater Intrusion:- Sea-Level Rise: As global temperatures rise, glaciers and ice sheets melt, and ocean water expands, leading to a steady increase in global sea levels. This rise in sea level directly pushes the saltwater interface further inland, increasing the risk of intrusion into freshwater sources.

- Over-extraction of Groundwater: Coastal regions are often densely populated, leading to high demand for freshwater for domestic, industrial, and agricultural purposes. The excessive pumping of groundwater from coastal aquifers reduces the freshwater pressure, allowing the denser saltwater to advance and fill the void. This is one of the most significant anthropogenic drivers of saltwater intrusion.

- Storm Surges and Coastal Flooding: Extreme weather events, such as hurricanes and cyclones, are becoming more frequent and intense due to climate change. These events can create powerful storm surges that inundate low-lying coastal areas with large volumes of saltwater. This leads to rapid and widespread contamination of surface soils and shallow aquifers.

- Tidal Fluctuations and Seasonal Variations: The natural ebb and flow of tides can cause temporary and localized saltwater intrusion. During high tides, saltwater can move further up estuaries and tidal creeks. Seasonal variations in rainfall and river discharge also play a crucial role. During dry seasons, reduced freshwater flow is less effective at repelling saltwater.

- Land Subsidence: The sinking of coastal land, often caused by the extraction of groundwater, oil, or gas, can exacerbate the effects of sea-level rise and increase the vulnerability of coastal areas to saltwater intrusion.

- Modifications to Coastal Landscapes: The construction of shipping channels, drainage canals, and other coastal infrastructure can alter natural water flow patterns. This can create new pathways for saltwater to penetrate inland.

The Salty Scourge: Impacts on Coastal Agriculture

The consequences of saltwater intrusion on coastal farms are far-reaching and can be devastating. Salt is a silent killer of crops, degrading soil health, reducing yields, and ultimately threatening the livelihoods of coastal farming communities.

1. Soil Salinization:When saltwater infiltrates agricultural land, the salt, primarily sodium chloride (NaCl), accumulates in the soil. This process, known as soil salinization, has several detrimental effects:

- Altered Soil Structure: High concentrations of sodium ions can disperse soil aggregates, leading to a loss of soil structure. This results in compacted soils with poor drainage and aeration. This makes it difficult for plant roots to penetrate and access water and nutrients.

- Nutrient Imbalance: Excess sodium can displace essential plant nutrients like calcium, magnesium, and potassium from the soil, creating nutrient deficiencies for crops.

- Reduced Water Infiltration: The breakdown of soil structure reduces the rate at which water can infiltrate the soil. This leads to increased surface runoff and waterlogging in some areas.

The presence of excess salt in the soil and irrigation water directly impacts plant growth and productivity through several mechanisms:

- Osmotic Stress: High salt concentrations in the soil create a higher osmotic potential. This makes it more difficult for plant roots to absorb water. Even when the soil is moist, plants can experience "physiological drought" because the water is too salty for them to take up. This leads to wilting, stunted growth, and reduced yields.

- Ionic Toxicity: Specific ions, particularly sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl-), can be toxic to plants at high concentrations. These ions can interfere with essential metabolic processes, damage cell membranes, and inhibit enzyme activity. Symptoms of ionic toxicity include leaf burn, necrosis (tissue death), and premature leaf drop.

- Nutrient Uptake Inhibition: The high concentration of sodium ions in the soil solution can compete with the uptake of essential nutrients like potassium (K+). Potassium is vital for many physiological functions in plants. This can lead to potassium deficiency and further impair crop growth.

The tolerance of crops to salinity varies significantly. Some crops, like rice, corn, and strawberries, are highly sensitive to salt. Others, such as barley, cotton, and certain varieties of asparagus and spinach, are moderately to highly tolerant. However, even salt-tolerant crops will experience yield reductions beyond a certain salinity threshold. The increasing salinization of coastal agricultural lands is forcing many farmers to abandon traditional crops and seek out more salt-tolerant alternatives. These may not always be as profitable or marketable.

3. Economic and Social Consequences:The agricultural impacts of saltwater intrusion ripple outwards, affecting the economic and social fabric of coastal communities:

- Reduced Farm Income: Lower crop yields and the potential for complete crop failure directly translate to reduced income for farmers. This can lead to financial hardship, debt, and the inability to invest in farm improvements.

- Land Abandonment: In severe cases, the land may become so degraded by salt that it is no longer viable for agriculture. This forces farmers to abandon their land. This can lead to the loss of generational farming knowledge and a decline in rural populations.

- Threats to Food Security: Coastal agriculture is a significant contributor to global food production. The loss of productive agricultural land due to saltwater intrusion poses a direct threat to local, regional, and even national food security.

- Loss of Livelihoods: The entire agricultural value chain, from farmworkers to input suppliers and food processors, can be negatively affected by the decline of coastal farming.

The Agro-Informatics Revolution: A New Frontier in Coastal Farm Management

In the face of this mounting crisis, the field of agro-informatics offers a beacon of hope. By integrating advanced technologies and data-driven approaches, agro-informatics provides a powerful toolkit for understanding, monitoring, and managing saltwater intrusion. Agro-informatics is the application of innovative ideas, techniques, and scientific knowledge from computer science to agriculture. It connects information technology with the management, analysis, and application of agricultural data to design more accurate and targeted interventions.

Core Components of Agro-Informatics for Saltwater Intrusion Management: 1. Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Systems (GIS):- Eyes in the Sky: Satellite imagery and aerial photography provide a large-scale, synoptic view of coastal agricultural landscapes. Multispectral and hyperspectral sensors on satellites can detect changes in vegetation health, soil moisture, and even soil salinity levels. By analyzing spectral indices like the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), scientists and land managers can identify areas that are under stress from salinity.

- Mapping the Threat: GIS is a powerful tool for integrating and analyzing various spatial datasets. Layers of information—such as elevation, land use, soil type, groundwater levels, and salinity measurements—can be combined to create detailed maps that visualize the extent and severity of saltwater intrusion. These maps are invaluable for identifying high-risk areas, planning mitigation strategies, and communicating the problem to stakeholders.

- Monitoring Land Use Change: Remote sensing and GIS can be used to track changes in land use over time. An example is the conversion of agricultural land to aquaculture (shrimp farming), which can often exacerbate saltwater intrusion.

- Real-Time Data from the Field: A network of sensors deployed in the field can provide continuous, real-time data on key environmental parameters. These sensors can measure:

Soil Salinity and Moisture: Electrical conductivity (EC) sensors buried in the soil can provide direct measurements of salinity levels.

Groundwater Salinity and Depth: Sensors placed in monitoring wells can track the level of the water table and its salinity. This provides an early warning of saltwater intrusion into the aquifer.

Surface Water Salinity: Sensors in rivers, estuaries, and irrigation canals can monitor the movement of saltwater inland.

- The Internet of Things (IoT) in Agriculture: These sensor networks are often connected to the internet, creating an "Internet of Things" for agriculture. This allows for the remote and automated collection of data, which can be transmitted to a central server for analysis and visualization.

- Making Sense of the Data: The vast amounts of data collected from remote sensing and sensor networks require sophisticated analytical techniques to extract meaningful insights. Big data analytics and machine learning algorithms can be used to:

Identify Patterns and Trends: Analyze historical data to understand the dynamics of saltwater intrusion and identify the key factors driving it in a particular location.

Predict Future Intrusion: Develop predictive models that can forecast the future extent and severity of saltwater intrusion under different climate change and water management scenarios. These models can help policymakers and farmers make proactive decisions.

Develop Early Warning Systems: By integrating real-time sensor data with predictive models, it is possible to create early warning systems that can alert farmers to an impending saltwater intrusion event. This gives them time to take protective measures.

- Numerical Modeling: Sophisticated numerical models, such as variable-density groundwater flow models (e.g., SEAWAT), can simulate the complex interactions between freshwater and saltwater in coastal aquifers. These models are essential for understanding the underlying physical processes and for evaluating the effectiveness of different management strategies.

- Targeted Interventions: The insights gained from agro-informatics can be used to implement precision agriculture techniques. Instead of applying water and other inputs uniformly across a field, farmers can use data to make targeted interventions:

Variable Rate Irrigation: Apply freshwater strategically to areas with higher salinity to help leach salts from the root zone.

Precision Fertilization: Apply nutrients only where they are needed, avoiding waste and reducing the risk of nutrient imbalances caused by salinity.

- Empowering Farmers with Information: Decision Support Systems (DSS) are software tools that integrate data, models, and expert knowledge to provide farmers with recommendations for managing their farms. A DSS for saltwater intrusion management might provide advice on:

Optimal irrigation scheduling.

The most suitable salt-tolerant crop varieties to plant.

* Land management practices to improve soil health.

Agro-Informatics in Action: Case Studies and Real-World Applications

The application of agro-informatics to combat saltwater intrusion is not just a theoretical concept; it is being actively implemented in vulnerable coastal regions around the world.

- The Mekong Delta, Vietnam: This low-lying delta is one of the world's most productive agricultural regions, but it is also highly vulnerable to saltwater intrusion. Researchers and government agencies are using a combination of remote sensing, GIS, and in-situ monitoring to track the movement of saltwater up the Mekong River and its distributaries. This information is used to inform the operation of sluice gates and to provide farmers with advisories on when to irrigate and what crops to plant. Machine learning models are being developed to provide more accurate and timely forecasts of salinity intrusion.

- The Netherlands: With a significant portion of its land below sea level, the Netherlands has centuries of experience in water management. Today, they are at the forefront of using agro-informatics to manage saltwater intrusion. A dense network of sensors monitors groundwater levels and salinity, providing real-time data for sophisticated water management models. This allows for the precise control of water levels in polders and the strategic use of freshwater resources to keep saltwater at bay.

- Bangladesh: In the coastal regions of Bangladesh, where millions of smallholder farmers are threatened by rising salinity, agro-informatics is being used to promote climate-resilient agriculture. GIS mapping has helped to identify areas at high risk of salinization. This information is being used to target interventions such as the introduction of salt-tolerant rice varieties and the promotion of alternative livelihoods like crab fattening in saline ponds.

- The Pajaro Valley, California: The coastal agricultural sector in this region is threatened by limited surface water and saltwater intrusion into its coastal aquifers, both of which are exacerbated by climate change. To address this, the Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency has implemented a managed aquifer recharge program. Hydrologic and water quality data from sensors throughout the slough network, and offshore conditions from ocean buoys and tide gauges, are being used to inform adaptive freshwater management strategies.

Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies Informed by Agro-Informatics

Agro-informatics does not just help us understand the problem of saltwater intrusion; it also provides the foundation for developing and implementing effective mitigation and adaptation strategies.

1. Enhanced Water Management:- Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR): This involves intentionally recharging coastal aquifers with freshwater from other sources, such as treated wastewater or excess surface water during the rainy season. Agro-informatics can help to identify the most suitable locations for MAR projects and to monitor their effectiveness.

- Optimized Irrigation: By using real-time soil moisture and salinity data, farmers can optimize their irrigation practices to use water more efficiently and to minimize the risk of waterlogging and salinization.

- Conjunctive Use of Surface Water and Groundwater: Agro-informatics can help to develop strategies for the integrated management of surface water and groundwater resources. This ensures that groundwater is used sustainably.

- Leaching of Salts: In areas where salinization has already occurred, the application of excess freshwater can be used to leach salts from the root zone. Agro-informatics can help to determine the optimal amount of water to apply for leaching without causing waterlogging.

- Improving Soil Health: The application of organic matter, such as compost and manure, and other soil amendments like biochar and gypsum can help to improve soil structure, increase water retention, and mitigate the negative effects of sodium on the soil.

- Land Leveling and Grading: Precision land leveling, guided by GPS technology, can improve surface drainage and prevent the ponding of saline water on fields.

- Promoting Salt-Tolerant Crops: Agro-informatics can help to identify areas that are suitable for growing salt-tolerant crops. This information can be disseminated to farmers through extension services and decision support systems.

- Integrated Agriculture-Aquaculture Systems: In some areas, it may be more sustainable to transition from traditional agriculture to integrated systems that combine the cultivation of salt-tolerant crops with saline aquaculture (e.g., shrimp or fish farming). GIS and remote sensing can be used to identify suitable areas for these systems.

- Informed Policymaking: The data and models generated through agro-informatics provide a strong scientific basis for the development of policies and regulations. These policies aim at managing groundwater extraction, protecting coastal ecosystems, and promoting climate-resilient agriculture.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Visualizations and decision support tools derived from agro-informatics can be powerful tools for engaging with stakeholders. These stakeholders include farmers, policymakers, and the public. They can raise awareness about the threat of saltwater intrusion and build consensus on the need for action.

The Road Ahead: Challenges and Opportunities

Despite its immense potential, the widespread adoption of agro-informatics for saltwater intrusion management faces several challenges:

- Cost and Accessibility: The technologies involved, such as remote sensing data and sensor networks, can be expensive. They may not be accessible to smallholder farmers in developing countries.

- Data Gaps and Quality: In many regions, there is a lack of long-term, high-quality data on groundwater levels, salinity, and other key parameters.

- Technical Expertise: The use of sophisticated data analysis and modeling tools requires specialized technical expertise. This may be lacking in many agricultural extension agencies.

- Bridging the Gap between Science and Practice: There is often a disconnect between the scientific research conducted in universities and research institutions and the practical needs of farmers on the ground.

However, the opportunities for advancing the field and overcoming these challenges are equally significant:

- Decreasing Costs of Technology: The cost of sensors, drones, and satellite data is steadily decreasing, making these technologies more accessible.

- Advances in Artificial Intelligence: Rapid advances in AI and machine learning are enabling the development of more powerful and accurate predictive models.

- Open-Source Data and Tools: The increasing availability of open-source satellite data and open-source software for GIS and data analysis is democratizing access to these powerful tools.

- Collaborative Platforms: The development of web-based platforms and mobile applications can help to bridge the gap between scientists and farmers. This can provide them with timely and actionable information.

Conclusion: A Call for a Data-Driven Future for Coastal Agriculture

Saltwater intrusion is a complex and insidious threat to coastal agriculture. It is a silent tide that is being pushed ever further inland by the forces of climate change and human activity. The stakes are incredibly high, with the livelihoods of millions of farmers and the food security of entire regions hanging in the balance.

In this high-stakes battle, agro-informatics has emerged as a game-changing ally. By providing the tools to see the unseen, to understand the complex interplay of forces at work, and to predict the future trajectory of this threat, agro-informatics is empowering us to move from a reactive to a proactive stance. It is enabling a shift towards a more precise, data-driven, and resilient form of coastal agriculture.

The journey ahead will require a concerted effort from scientists, policymakers, extension agents, and farmers themselves. It will require continued investment in research and development, a commitment to building local capacity, and a willingness to embrace new technologies and new ways of thinking. But with the power of agro-informatics as our guide, we can navigate the challenges of saltwater intrusion. We can work towards a future where coastal farms not only survive but thrive, continuing to nourish a growing world population for generations to come. The fusion of data and the delta is not just a scientific curiosity; it is an essential strategy for survival in the 21st century.

Reference:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saltwater_intrusion

- https://dropconnect.com/what-is-saltwater-intrusion/

- https://www.eesi.org/articles/view/saltwater-intrusion-a-slow-onset-climate-crisis-jeopardizing-americas-coastal-farms

- https://www.gmri.org/projects/understanding-saltwater-intrusion/

- https://www.vaia.com/en-us/explanations/environmental-science/geology/saltwater-intrusion/

- https://journals.plos.org/water/article?id=10.1371/journal.pwat.0000121

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39908905/

- https://www.quora.com/What-is-agro-informatics

- https://www.iibs.edu.in/news/importance-of-agro-informatics-abm-colleges-in-bangalore-931

- https://www.inf.elte.hu/dstore/document/1796/agroinformatics-zentai6%20%281%29.pptx

- https://www.fao.org/agroinformatics/en

- https://www.kisangates.com/agro-informatics.html

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381892216_Assessment_of_the_vulnerability_of_coastal_agriculture_to_seawater_intrusion_using_remote_sensing_GIS_and_Multi-Criteria_Decision_Analysis

- https://core.ac.uk/download/525100926.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359711417_Managing_Saltwater_Intrusion_and_Agricultural_Practices_along_the_Bogacay_River_Turkey_Effects_from_Excavation_and_Land_Source_Pollution

- https://climateadapt.ucsd.edu/helping-water-managers-and-farmers-address-saltwater-intrusion/

- https://www.studysmarter.co.uk/explanations/environmental-science/geology/seawater-intrusion/

- https://iwaponline.com/jwcc/article/12/5/1327/76653/Potential-management-practices-of-saltwater

- https://portal.nifa.usda.gov/web/crisprojectpages/1015143-adapting-agroecosystems-to-saltwater-intrusion-and-mitigating-nutrient-losses-from-coastal-farmlands.html