Deep beneath the North American continent, where the bedrock seems solid and immutable, a quiet revolution is taking place. It is not a revolution of politics or culture, but of geology. Two massive scars in the Earth’s crust—one an ancient, healed wound and the other a still-festering tear—are forcing scientists to rethink the continent’s energy potential. These are the Great Rifts of North America: the dormant, billion-year-old Mid-Continent Rift and the active, stretching Rio Grande Rift.

For decades, these subterranean giants were curiosities for academic geologists. Today, they are the subjects of a modern gold rush. But this time, the treasure isn't gold—it is heat and hydrogen. From the high deserts of New Mexico to the iron-rich depths of the Great Lakes, these ancient rifts are "warming" North America in a way that has nothing to do with climate change and everything to do with a clean energy future.

Part I: The Living Tear – The Rio Grande Rift

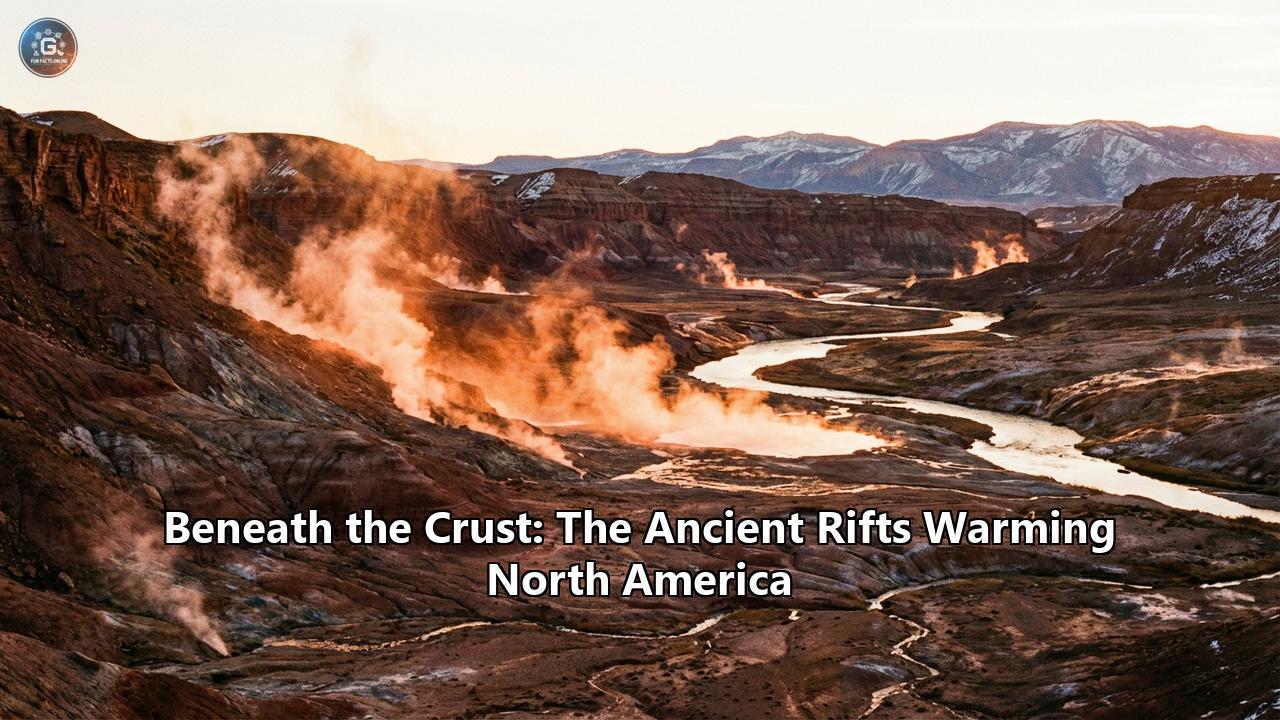

To understand the heat beneath our feet, one must first look to where the Earth is still moving. Stretching from the towering peaks of Leadville, Colorado, down through New Mexico and into the dust of Chihuahua, Mexico, lies the Rio Grande Rift. It is one of the few places on Earth where a continent is actively pulling itself apart.

The Geology of a Breakup

The Rio Grande Rift is a tectonic infant compared to the rest of the continent, having begun its slow stretch only about 29 to 35 million years ago. As the Colorado Plateau pulls away from the Great Plains, the Earth's crust thins, stretching like taffy. In most places, the continental crust is 40 kilometers thick. Beneath the Rio Grande Rift, it has thinned to as little as 30 kilometers.

This thinning has a profound consequence: it brings the hot, churning mantle closer to the surface.

"The Earth is a heat engine, and the Rio Grande Rift is one of its exhaust pipes," explains Dr. Sarah Miller, a geophysicist specializing in extensional tectonics. "Because the crust is so thin here, the natural radioactive heat from the Earth's core and mantle doesn't have far to travel. It literally warms the ground from below."

The Geothermal Corridor

This geological reality has turned the rift zone into a hotbed—literally—for geothermal energy. The state of New Mexico, which sits squarely atop the rift, has long been famous for its hot springs. Towns like Truth or Consequences were renamed for their thermal baths, fed by waters heated deep underground and forced to the surface through fault lines.

But the potential goes far beyond spa tourism. The high heat flow makes the region a prime candidate for Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS). Unlike traditional geothermal energy, which requires naturally occurring pockets of steam (like The Geysers in California), EGS involves drilling deep into hot, dry rock and injecting water to create artificial steam.

In the San Luis Basin and the Albuquerque Basin, the geothermal gradient is steep. While the average temperature of the Earth increases by about 25°C per kilometer of depth, in the rift zone, it can rise by 40°C to 50°C or more. This "superheated" basement rock means that clean, baseload electricity—power that runs 24/7, unlike wind or solar—is accessible at shallower, cheaper depths than almost anywhere else in the US.

Already, facilities like the Lightning Dock Geothermal Plant in New Mexico are proving the concept. By tapping into the rift’s fracture network, they are harvesting the heat of the mantle to power thousands of homes. As drilling technology advances, experts predict the Rio Grande Rift could become the "Saudi Arabia of Geothermal," providing gigawatts of carbon-free heat.

Part II: The Sleeping Giant – The Mid-Continent Rift

If the Rio Grande Rift is a visible, active heat source, the Mid-Continent Rift (MCR) is its silent, mysterious ancestor. Buried under miles of sedimentary rock and glacial till, this rift curves like a massive scar for 1,800 miles from Kansas, up through Lake Superior, and down into Michigan.

The Rift That Failed

1.1 billion years ago, North America nearly split in two. A massive plume of magma rose from the mantle, tearing the continent apart. Lava poured out in volumes that are hard to comprehend—millions of cubic kilometers of basalt, layer upon layer, creating a volcanic pile 20 miles thick. Then, for reasons geologists are still debating, the rifting stopped. The continent healed, compressing the rift and burying the volcanic rock.

For a century, the MCR was known primarily for copper. The Keweenaw Peninsula in Michigan, formed by the rift’s exposed spine, was the epicenter of a copper boom in the 1800s. But recently, the MCR has revealed a new secret, one that is generating a different kind of "heat" in the scientific community: Geologic Hydrogen.

The Serpentinization Engine

The volcanic rocks that fill the Mid-Continent Rift are rich in iron and magnesium—specifically, a mineral called olivine. When olivine meets water under high pressure and temperature, it undergoes a chemical reaction called serpentinization.

This reaction is remarkable for two reasons:

- It is Exothermic: The reaction releases heat. While not enough to melt rock, it warms the surrounding fluids, creating a self-sustaining reactor deep underground.

- It Produces Hydrogen: As the water reacts with the iron in the rock, the oxygen is stripped away to form new minerals (serpentinite and magnetite), leaving pure hydrogen gas ($H_2$) as a byproduct.

"We used to think hydrogen couldn't exist in the ground," says Dr. Geoffrey Ellis, a research geologist with the USGS. "We thought it was too small a molecule, that it would escape or be eaten by microbes. But we were wrong. The Mid-Continent Rift is essentially a giant hydrogen battery that has been running for a billion years."

The "Gold Hydrogen" Rush

This naturally occurring hydrogen is often called "gold hydrogen" or "white hydrogen" to distinguish it from "green hydrogen" (made from electrolysis) or "grey hydrogen" (made from natural gas). It is the holy grail of energy: carbon-free fuel that is produced continuously by the Earth itself.

In 2019, a serendipitous discovery in a test well in Nebraska—drilled right into the southern arm of the MCR—revealed hydrogen concentrations orders of magnitude higher than expected. This sparked a frenzy. Geologists realized that the MCR’s unique structure—iron-rich rocks capped by thick, impermeable seals of sedimentary stone—is the perfect geological trap.

The "warming" here is economic and chemical. The serpentinization process is continuously generating energy deep beneath the cornfields of Iowa and the forests of Minnesota. If this hydrogen can be tapped, it could power the heavy industry of the Midwest—steel mills, trucking fleets, and fertilizer plants—without emitting a single gram of CO2.

Part III: A Tale of Two Rifts

The Rio Grande Rift and the Mid-Continent Rift tell the story of North America’s tectonic struggle, but they also offer complementary solutions to the climate crisis.

| Feature | Rio Grande Rift | Mid-Continent Rift |

| :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Status | Active, stretching | Ancient, failed (1.1 Ga) |

| Location | CO, NM, TX, Mexico | KS, NE, IA, MN, WI, MI |

| Primary Resource | Geothermal Heat (Electricity & Direct Use) | Geologic Hydrogen (Fuel & Chemical Feedstock) |

| Mechanism | Mantle upwelling & crustal thinning | Chemical reaction (Serpentinization) |

| "Warming" Type | Physical thermal heat | Exothermic reaction & clean fuel potential |

The Convergence of Technologies

Interestingly, the technologies needed to harvest these resources are converging. The drilling techniques developed for the shale oil boom are now being adapted for the high heat of the Rio Grande and the deep, hard rock of the Mid-Continent Rift.

Furthermore, the two rifts could work in tandem. The excess heat from the Rio Grande Rift could be used to drive high-efficiency electrolysis, creating green hydrogen to supplement the geologic hydrogen from the north. Conversely, the hydrogen pipelines of the future could connect the industrial hubs of the Midwest (fed by the MCR) to the growing cities of the Southwest (powered by the Rio Grande).

Part IV: The Environmental Imperative

The discovery of these "warming" rifts comes at a critical moment. As North America seeks to decarbonize, the limitations of wind and solar—intermittency and land use—are becoming apparent. The rifts offer what the grid desperately needs: firm, clean power.

Geothermal energy runs 24 hours a day. Geologic hydrogen can be stored in salt caverns and burned when needed, acting as a clean battery for the grid. Tapping into these ancient geological features requires a minimal surface footprint compared to sprawling solar farms or wind arrays.

However, the path is not without challenges. Drilling deep is expensive. There are concerns about induced seismicity (man-made earthquakes) if fluid injection isn't managed carefully, particularly in the active faults of the Rio Grande. In the Mid-Continent Rift, the challenge is exploration—finding the "sweet spots" where hydrogen accumulates in extractable quantities.

Conclusion: The Heat Beneath Us

For millions of years, the heat of the Rio Grande Rift has been dissipating into the desert air, and the hydrogen of the Mid-Continent Rift has been trickling slowly through the cracks of the crust. We walked above them, unaware that the ground beneath us held the keys to a new industrial age.

"The Ancient Rifts Warming North America" is not a headline about catastrophe, but about opportunity. It is the story of a continent that is geologically alive, offering up its ancient heat and its hidden chemistry to power the future. As drills bite deeper into the basalt and the granite, we are finally learning to tap into the pulse of the planet itself. The rifts nearly broke the continent apart once; now, they may be the very thing that holds our energy future together.

Reference:

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321857813_A_Geodynamic_model_for_melt_generation_and_evolution_of_the_Mid-Continental_Rift

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serpentinization

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251729685_Serpentinization_and_heat_generation_constraints_from_Lost_City_and_Rainbow_hydrothermal_systems1