The Baltic Sea is a graveyard of landscapes. Beneath its cold, brackish waves lie not just the wrecks of wooden ships and the rusted hulks of modern wars, but entire worlds—forests that once rustled in the wind, river valleys where herds of giant elk grazed, and lakeshores where the smoke of hearth fires curled into the pale prehistoric sky. For millennia, these realms have been lost to the rising waters, their stories erased by the slow, inexorable grind of the post-glacial thaw.

But in the autumn of 2021, the sea gave up a secret.

Roughly 10 kilometers off the coast of Rerik, Germany, in the Bay of Mecklenburg, a team of researchers and students from Kiel University were conducting a routine training exercise. They were there to map the seafloor, to teach the next generation of geophysicists how to read the topography of the abyss. As the research vessel Alkor cut through the chop, its multibeam sonar painted a picture of the bottom, 21 meters below. The display should have shown the chaotic scatter of glacial till—the random debris left behind by the retreating ice sheets.

Instead, it showed a line.

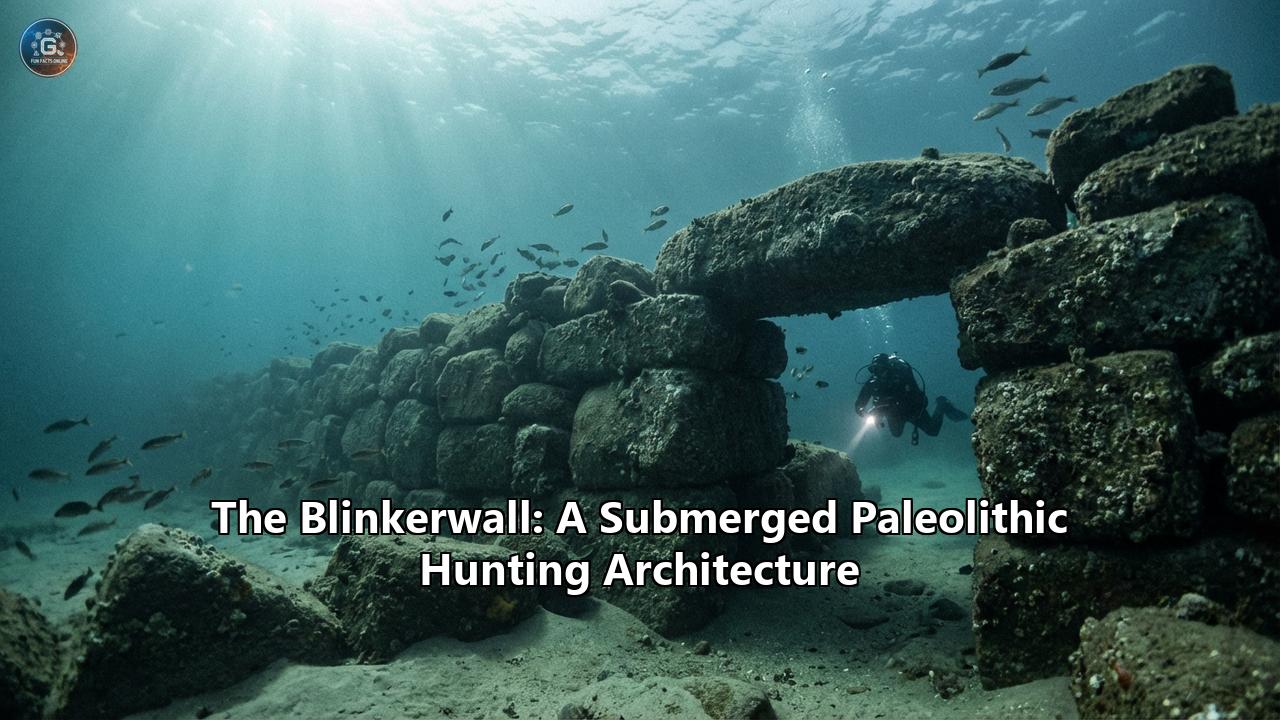

It was faint at first, a subtle anomaly in the acoustic data. But as the resolution sharpened, the randomness of nature fell away, replaced by the unmistakable order of intent. There, stretching for nearly a kilometer across the drowned ridge, was a wall. It was not a towering fortification of empire, but a low, deliberate ribbon of stone, constructed with a precision that defied the chaos of the ice age.

This was the Blinkerwall. And as the world would soon learn, it was not just a pile of rocks. It was a message from the deep past, a 10,000-year-old architectural marvel that would rewrite our understanding of the Stone Age, revealing a society of sophistication, cooperation, and engineering prowess that had been hidden in plain sight for eighty-five centuries.

Part I: The Accidental Discovery

The history of archaeology is often written by accident. The Rosetta Stone was found by soldiers reinforcing a fort; the Terracotta Army was discovered by farmers digging a well. The Blinkerwall belongs to this lineage of serendipity.

When Dr. Jacob Geersen and his colleagues first stared at the sonar images, the excitement was tempered by scientific skepticism. The Baltic seafloor is a messy place. The Weichselian glaciation, which covered this region in kilometers of ice until about 12,000 years ago, was a messy sculptor. It left behind moraines, eskers, and erratic boulders—giant rocks dropped by melting icebergs. A straight line of stones could, in theory, be a "push moraine," a ridge shoved up by the advancing ice.

But the more they looked, the less natural it seemed. Nature rarely draws straight lines, and it almost never arranges stones by size. The sonar revealed a pattern: large, immovable boulders, too heavy for humans to shift, were spaced out at irregular intervals. But connecting these heavy anchors were thousands of smaller stones, football-sized rocks that had been carefully collected and placed to form a continuous barrier.

To confirm their suspicions, the team returned. They deployed autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) to glide just meters above the structure, capturing high-resolution optical images. They sent down divers, who swam through the gloom to touch the stones with their own hands.

What they found was undeniable. The wall ran for 971 meters (roughly 0.6 miles). It was less than a meter high, a low hurdle rather than a fortress wall. It didn't enclose anything; it didn't circle a village or protect a camp. It simply ran, purposeful and distinct, along the flank of a submerged ridge.

The most damning piece of evidence against a natural origin was the "angle of repose." In natural ridges, stones tumble and pile up chaotically. Here, the smaller stones were packed intentionally between the larger boulders. If a glacier had done this, it would have smeared the stones across the landscape. If a tsunami had done it, the stones would be sorted by weight in a completely different way.

This was built. And based on the geological history of the Bay of Mecklenburg, the builders had walked this land when it was dry tundra, long before the Baltic Sea swallowed it whole.

Part II: The Drowned World of the North

To understand the Blinkerwall, one must first unsee the map of modern Europe. Forget the familiar coastline of Germany and Denmark. Forget the Baltic Sea as a navigational barrier.

Travel back 11,000 years, to the transition between the Late Paleolithic and the Early Mesolithic. The world is waking up from the long nightmare of the Ice Age. The massive glaciers that once crushed Scandinavia are retreating, but their legacy is everywhere.

The Bay of Mecklenburg does not exist. Instead, you are standing in a vast, open landscape. The air is crisp and cold, smelling of sedge and damp earth. To the north, the great Baltic Ice Lake—a massive freshwater body dammed by the retreating glaciers—is evolving. The land here is a steppe-tundra mosaic, a rolling plain of grasses, dwarf birch, and willow.

It is a " Serengeti of the North."

The landscape is alive. Herds of wild horses thunder across the plains. Giant Irish elk, with antlers spanning three meters, browse in the scrub. But the true king of this ecosystem, the lifeblood of the human inhabitants, is the reindeer.

The reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) is more than just a source of meat. It is a walking department store. Its hide provides coats, tents, and blankets that are unmatched in insulation. Its antlers are carved into harpoons, needles, and tool handles. Its sinews become thread and bowstrings. Its bones are cracked for nutrient-rich marrow. For the hunter-gatherers of this era—likely people of the Hamburgian or Ahrensburgian cultures—the reindeer is life itself.

But the reindeer is also a creature of habit. It is a migratory animal, moving in vast herds between winter sheltering grounds and summer grazing pastures. These herds flow like water across the landscape, following the path of least resistance. They avoid steep climbs, they hug lakeshores, and they follow ridges.

It was this predictability that the builders of the Blinkerwall sought to exploit.

The wall is located on the southern flank of a ridge that, 11,000 years ago, ran parallel to a lake. This lake, now a submerged depression in the seafloor, was the key. The wall was not a fence to keep animals in; it was a funnel to guide them to their death.

Part III: The Architecture of Slaughter

The Blinkerwall is a "drive lane," a piece of hunting architecture designed to manipulate animal behavior.

Imagine the hunt. It is autumn. The days are shortening, and the first frosts are coating the grass. The reindeer herds are on the move, thousands of animals drifting south or west, their hooves clicking, their breath steaming in the cold air.

The hunters know they are coming. They have watched the herds for generations. They know that when the reindeer hit the ridge, they will follow it.

But on the open steppe, a reindeer is faster than a human. A spear thrown from a distance is a low-percentage shot. To kill enough animals to survive the coming winter, the hunters need an advantage. They need to control the movement of the herd.

This is where the wall comes in.

As the herd moves along the ridge, they encounter the line of stones. It is not high—a reindeer could easily jump over a one-meter wall. But herd animals are path-followers. When confronted with a linear barrier, especially one that runs parallel to their direction of travel, they tend to follow it rather than cross it. This is a behavioral quirk known as the "blinker effect" (though the wall’s name likely comes from a location or research designation rather than this ethological term).

The wall gently nudges the herd. It creates an artificial boundary. On one side is the ridge; on the other, the rising waters of the paleolake. The reindeer are funneled into a "bottleneck," a narrowing corridor between the water and the wall.

At the end of the wall, or perhaps at a gap intentionally left in the structure, the trap springs.

This was not a hunt; it was a harvest.

Hunters, camouflaged in the grass or hiding behind the larger boulders (which may have served as "blinds"), would rise up. Armed with spears tipped with flint tanged points—the signature weapon of the Ahrensburgian culture—they would launch a coordinated assault.

In the chaos, the reindeer would panic. Hemmed in by the wall on one side and the lake on the other, they would have nowhere to run. Some might be driven into the water, where they are slow swimmers, vulnerable to hunters waiting in skin boats or dugouts.

The Blinkerwall transforms the landscape itself into a weapon. It turns the vast, open tundra into a kill zone.

Part IV: The Builders – A Feat of Cooperation

The existence of the Blinkerwall shatters a long-held myth about Stone Age people.

For decades, the popular image of Paleolithic hunter-gatherers was one of small, desperate bands. We imagined them living hand-to-mouth, constantly on the move, with no time or resources to build permanent structures. We thought of them as "opportunists," taking what nature offered but rarely imposing their will on the land.

The Blinkerwall proves this wrong.

Building a kilometer-long wall requires more than just muscle; it requires planning, leadership, and mass cooperation.

The structure contains over 1,600 stones. The heavy boulders were already there, dropped by glaciers, but the 1,400 smaller stones had to be collected. This meant scouring the surrounding landscape, carrying rocks weighing 10 to 50 kilograms over distances of hundreds of meters.

This was not the work of a single family group. It implies a "seasonal aggregation." Several bands of hunters, perhaps totaling hundreds of people, must have come together. They had to agree on the plan. Someone had to design the route. Someone had to direct the labor. Someone had to feed the workers while they built.

This suggests a social complexity far beyond "primitive" survival. It implies:

- Territoriality: You don't build a megastructure if you don't intend to stay, or at least return to the same spot year after year. The Blinkerwall was a claim on the land.

- Resource Management: These people weren't just hunting; they were managing the herd. They were ensuring a surplus of food that could be smoked, dried, and stored for the winter.

- Social Stratification: Did the person who designed the wall get a larger share of the meat? Was there a class of "architects" or "hunt masters"?

The Blinkerwall puts the Baltic hunters on par with the builders of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey. While they weren't building temples, they were mobilizing labor for a monumental task. It suggests that the capacity for large-scale construction predates agriculture by thousands of years.

Part V: A Global Phenomenon

The Blinkerwall is unique in Europe, but it is not alone in the world. It connects the Baltic to a global tradition of "hunting architecture."

- The Desert Kites of the Levant: In the deserts of Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Syria, pilots in the 1920s noticed strange shapes on the ground. These "kites"—vast stone funnels leading to killing pits—were used to hunt gazelle. Like the Blinkerwall, they used low walls to guide animals. Some of these date to the same period as the Blinkerwall, suggesting a convergent evolution of human ingenuity.

- The Caribou Drive Lanes of Lake Huron: Thousands of miles away, beneath the waters of the Great Lakes in North America, archaeologists found the "Drop 45" drive lane. Built by Paleo-Indians to hunt caribou (the North American cousin of the reindeer), it shares a striking resemblance to the Blinkerwall. It, too, is submerged, preserved by rising water levels.

- The Norwegian High Mountain Systems: In the mountains of Norway, ancient reindeer trapping systems using stone cairns and wooden fences have been found. These are often younger than the Blinkerwall, but they show that this hunting technique remained effective for millennia.

The Blinkerwall is the missing link in this global picture. It connects the Middle East to the Americas, showing that wherever humans and herd animals co-existed, humans figured out the geometry of the slaughter.

Part VI: The Great Drowning

If the Blinkerwall was so effective, why was it abandoned?

The answer lies in the catastrophe that ended the Stone Age.

Around 8,500 years ago, the climate warmed. The great ice sheets of Scandinavia melted rapidly. The sea levels rose. The Baltic basin, which had been a fluctuating mix of fresh and salt water, began to fill.

The Littorina Transgression was a slow-motion flood. Year by year, the shoreline crept inland. The paleolake beside the Blinkerwall expanded, eventually merging with the rising sea. The grassy plain turned into a marsh, then a lagoon, and finally, the open sea.

The reindeer moved north, following the retreating cold. The birch forests became dense oak and hazel woodlands, changing the game. The era of the open steppe hunt was over.

The hunters adapted or died out. The Mesolithic cultures that followed, like the Ertebølle, were fishermen and coastal foragers. They built fish weirs of wood (which rot away), not stone walls for reindeer.

The Blinkerwall was left behind. The water rose over the stones. Algae coated the granite. Sediment drifted down, burying the base of the wall but leaving the top exposed.

In a twist of irony, the flood that destroyed the hunters' world is what saved their creation. Had the wall remained on dry land, it would have been destroyed. Farmers in the Bronze Age would have cleared the stones for fields. Medieval builders would have stolen the rocks for castles or churches. Modern roads would have paved over it.

Protected by the oxygen-poor, calm waters of the Baltic, the Blinkerwall remained frozen in time, a pristine snapshot of a lost day 10,000 years ago.

Part VII: The Future of the Deep

The discovery of the Blinkerwall is just the beginning. It has launched a new era of underwater archaeology in the Baltic, spearheaded by projects like SEASCAPE.

This three-year interdisciplinary project aims to reconstruct the lost landscapes of the Baltic. Using the Blinkerwall as a "Rosetta Stone," researchers are now re-examining sonar data from across the region. They are asking: What else is down there?

Are there base camps where the hunters slept? Are there "butchery sites" filled with reindeer bones and broken flint tools? Is there a "second wall" buried in the sediment, as some theories suggest, which would have created a true double-walled chute?

The Blinkerwall has taught us that the seafloor is not empty space. It is a drowned archive. It reminds us that our current coastlines are temporary. The humans of the Blinkerwall likely watched the sea rise with the same anxiety we feel today. They saw their hunting grounds disappear; they saw their world change.

As we stare at the sonar images of those 1,673 stones, we are looking at a monument to human resilience. We see a people who looked at a vast, intimidating landscape and said, We can shape this. We see the birth of engineering. We see the first stone laid in the long wall of human civilization.

The Blinkerwall is silent now, visited only by cod and currents. But if you listen closely to the data, you can almost hear the thundering hooves, the shouts of the hunters, and the splash of water in a world that used to be.

Reference:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GyydFznWnnQ

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/stone-age-wall-discovered-beneath-the-baltic-sea-helped-early-hunters-trap-reindeer-180983783/

- https://www.anthropology.net/p/the-blinkerwall-a-stone-age-megastructure

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zw-558TUiwk

- https://archaeology.org/news/2024/02/13/240214-baltic-sea-blinkerwall/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlJU_C8hA6g

- https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2312008121

- https://www.reddit.com/r/history/comments/1avo2il/stone_age_wall_discovered_beneath_the_baltic_sea/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17770437/

- https://www.crslr.de/projects/seascape

- https://www.leibniz-earth-and-societies.de/en/translate-to-english-mainnavigation/news/current-news/newsdetails/are-there-stone-age-megastructures-on-the-baltic-sea-floor-research-project-seascape-starts-with-kick-off-at-the-iow