Introduction: The Star in the Bottle

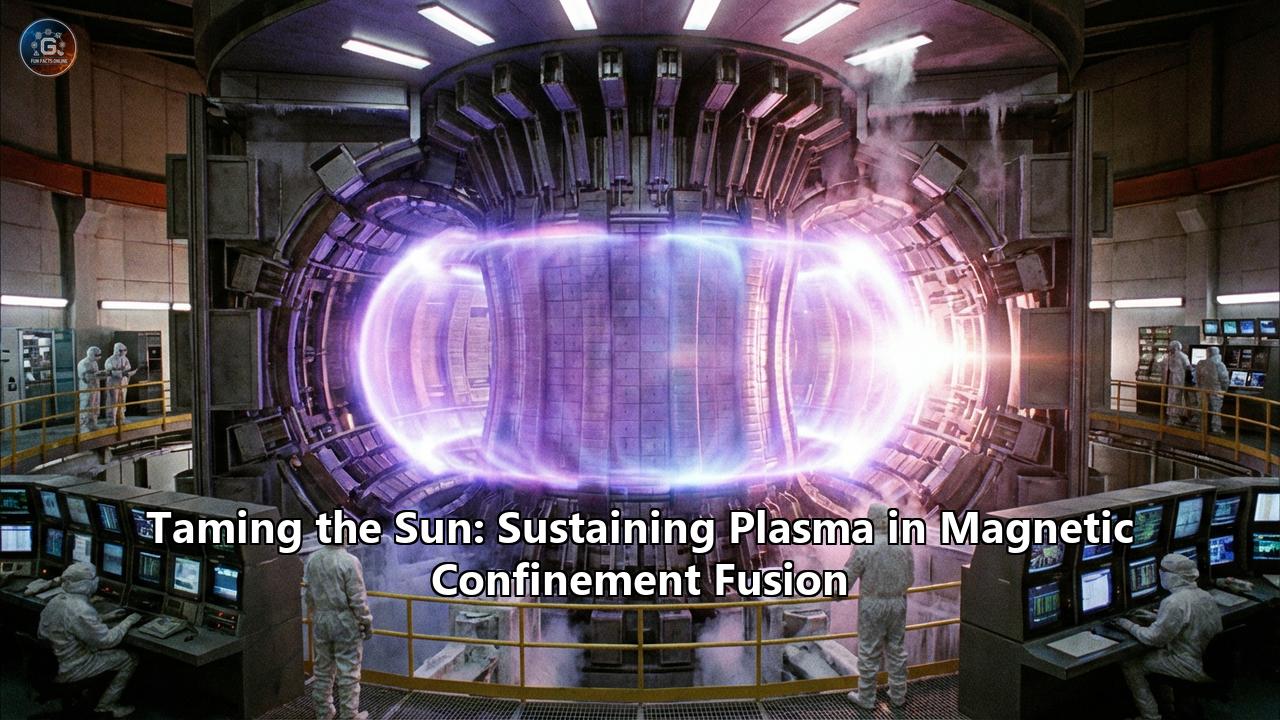

Imagine holding a piece of the sun. Not metaphorically, but literally—a writhing, blindingly bright wisp of star-stuff, heat so intense it would vaporize any physical container in the known universe. This is not science fiction; it is the daily reality of magnetic confinement fusion (MCF). For decades, the quest to replicate the power source of the stars has been described as the "holy grail" of clean energy. It promises a future free from carbon emissions, free from long-lived radioactive waste, and fueled by isotopes found abundantly in seawater.

But the catch has always been the "bottle." How do you hold a substance that must be heated to 150 million degrees Celsius—ten times hotter than the core of the sun—without it touching the walls? The answer lies in the invisible, non-material bars of a magnetic cage.

As we stand in late 2024 and move into 2025, the narrative of fusion is shifting. It is no longer just a scientific experiment; it is an industrial race. We have moved from simply creating plasma to the far more difficult challenge of sustaining it. The difference is profound. Lighting a match is easy; keeping a flame alive in a hurricane is an entirely different engineering challenge. This article explores the cutting-edge physics, the monumental engineering, and the fierce competition defining this pivotal moment in human history.

Part I: The Physics of the Impossible

To understand why sustaining plasma is so difficult, we must first appreciate the unruly nature of the beast. Plasma is often called the fourth state of matter, but that bland label hides its chaotic personality. It is an ionized gas, a soup of stripped electrons and naked nuclei buzzing with electric charge. Because it is charged, it responds to magnetic fields, which allows us to trap it.

The Instability Problem

In a magnetic confinement device, such as a tokamak or stellarator, the goal is to keep the plasma stable. But plasma fights back. It is susceptible to "instabilities"—wobbles, kinks, and tears in the magnetic fabric. Imagine trying to hold a balloon made of jelly with rubber bands; squeeze too hard in one place, and it bulges out in another.

One of the most notorious adversaries is the Edge Localized Mode (ELM). These are sudden, violent bursts of energy that erupt from the edge of the plasma, similar to solar flares on the sun. If an ELM hits the interior wall of a reactor, it can melt components like tungsten tiles in milliseconds. Sustaining plasma means taming these ELMs, smoothing out the turbulence so the "jelly" stays within the "rubber bands."

The Temperature-Confinement Dance

Fusion requires three conditions to be met simultaneously, known as the Lawson Criterion:

- Temperature: The fuel (usually Deuterium and Tritium) must be hot enough to overcome electrostatic repulsion.

- Density: There must be enough particles to collide and fuse.

- Confinement Time: The heat must be trapped long enough for the reaction to become self-sustaining.

Tokamaks are excellent at temperature and density but struggle with confinement time due to disruptions. Stellarators are naturally stable and can hold plasma indefinitely but struggle to reach the necessary temperatures. The current era of research is about hybridizing these strengths—using advanced magnets and control systems to make tokamaks more stable and stellarators hotter.

Part II: The Architectural Rivals

The battle for fusion dominance is currently fought between two primary machine designs, each with a radically different philosophy.

The Tokamak: The Doughnut of Power

The tokamak (a Russian acronym for "toroidal chamber with magnetic coils") is the workhorse of fusion. It looks like a giant hollow doughnut.

- How it works: It uses massive external magnets to create a toroidal (ring-shaped) field, combined with a central solenoid that induces a massive electrical current inside the plasma itself. This current creates a secondary poloidal field, twisting the magnetic lines into a helix that traps the particles.

- The Flaw: That internal current is a double-edged sword. It heats the plasma efficiently, but it can also snap. If the current is disrupted, the magnetic cage collapses in a "disruption event," slamming the thermal energy into the walls with the force of a dynamite stick.

- Current Champion: The ITER project in France is the king of tokamaks. A 35-nation collaboration, it is a beast of steel and concrete designed to be the first machine to yield net energy (Q > 10). However, its sheer size has made it slow. In 2024, ITER announced a major "re-baselining," pushing its full operations to 2035. This delay has opened the door for agile private competitors.

The Stellarator: The Twisted Ribbon

If the tokamak is a doughnut, the stellarator is a cruller twisted by a surrealist artist.

- How it works: Instead of inducing a current in the plasma, the stellarator relies entirely on external coils twisted into insanely complex 3D shapes. These coils generate the helical field directly.

- The Advantage: Because there is no driven current in the plasma, stellarators are immune to the violent disruptions that plague tokamaks. They are inherently "steady-state"—once you turn them on, they can theoretically run forever.

- The Challenge: Designing and building these twisted coils requires extreme precision. A deviation of a millimeter can ruin the confinement.

- The Renaissance: For decades, stellarators were seen as too hard to build. But supercomputers and 3D printing have changed the game. The Wendelstein 7-X in Germany has proven that optimized stellarators work, and Princeton’s MUSE project recently built a stellarator using permanent magnets and 3D-printed shells, proving they can be cheap and simple.

Part III: The Space Race of the 2020s

While government projects like ITER slog forward, the private sector has exploded with a "SpaceX for Fusion" mentality. Over $10 billion in private capital has flooded the market, driving aggressive timelines that aim to put fusion on the grid by the 2030s.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS): The Magnet Revolution

Spun out of MIT, CFS is betting the farm on High-Temperature Superconducting (HTS) magnets.

- The Breakthrough: Traditional fusion magnets use niobium-tin and must be cooled to 4 Kelvin (-269°C). CFS uses a new material, REBCO (Rare Earth Barium Copper Oxide) tape, which can operate at 20 Kelvin and, crucially, generate vastly stronger magnetic fields.

- Why it matters: A stronger magnet means a smaller bottle. CFS's demo reactor, SPARC, is currently under construction in Devens, Massachusetts. It is a fraction of the size of ITER but aims to achieve the same net-energy goal. In 2025, they are assembling the vacuum vessel—the steel heart of the machine—and winding the HTS magnets that will define the industry's future.

Helion Energy: The Pulsed Maverick

Helion is the dark horse. They don't use a tokamak or a stellarator. They use a Field Reversed Configuration (FRC).

- The Pulse: Instead of a steady burn, Helion’s machine, Polaris, acts like a diesel engine. It shoots two rings of plasma at each other from opposite ends of a tube. They collide in the center, compress, fuse, and then expand.

- Direct Capture: This is Helion’s "killer app." As the fusion plasma expands, it pushes back against the magnetic field. By Faraday’s Law of Induction, this change in magnetic field generates electricity directly in the coils. No steam turbines, no boiling water, no heat exchangers.

- Status: Backed by Microsoft and OpenAI’s Sam Altman, Helion is currently building Polaris in Washington State. They aim to demonstrate electricity generation by 2028—a deadline that skeptics call impossible and supporters call revolutionary.

Tokamak Energy: The Spherical Contender

Based in the UK, this company favors the Spherical Tokamak, which looks more like a cored apple than a doughnut. This shape is more efficient, holding higher pressure plasma with a weaker magnetic field.

- Record Breakers: Their ST40 reactor recently achieved plasma temperatures of 100 million degrees, a record for a private company.

- HTS Synergy: Like CFS, they are pioneering HTS magnets. Their "Demo4" magnet system is testing "no-insulation" coils, a robust design that can survive failures better than insulated counterparts.

Part IV: The "Nervous System" of the Star (AI & Control)

Sustaining plasma isn't just about heavy metal; it's about intelligence. Plasma is turbulent and chaotic. Trying to control it with standard PID controllers is like trying to drive a Formula 1 car on ice using only a stopwatch. You need to react to skids before they happen.

Enter Artificial Intelligence.

DeepMind and "Plasma Sculpting"

In a landmark collaboration with the Swiss Plasma Center, Google DeepMind trained a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) agent to control the TCV tokamak.

- The Feat: The AI wasn't just told "keep it stable." It was given a goal—"make two droplets of plasma at the same time"—and it figured out which knobs to turn on the magnetic coils to make it happen. It learned to "sculpt" the plasma in real-time, reacting to millisecond-scale changes that no human could predict.

The DIII-D Breakthrough

At the DIII-D National Fusion Facility in San Diego, researchers from Princeton recently deployed an AI controller that specifically targets tearing instabilities.

- Pre-cognition: The AI analyzes data from hundreds of sensors and predicts a tear before it rips the magnetic cage. It then subtly adjusts the magnetic beams to heal the tear. This ability to "heal" the plasma in real-time is the key to moving from short pulses to the continuous, steady-state operation needed for a power plant.

Part V: The Armor of the Gods (Materials Science)

If the magnets are the bottle, the First Wall and Divertor are the armor plating. This is where the rubber meets the road—or rather, where the 100-million-degree plasma exhaust meets solid matter.

The Tungsten Dilemma

The material of choice is Tungsten. It has the highest melting point of any metal (3,422°C) and doesn't absorb the precious Tritium fuel like carbon does.

- The Problem: Tungsten is brittle. Under the intense bombardment of neutrons from the fusion reaction, it can crack.

- The Solution: Scientists are developing Tungsten Fiber-Reinforced Tungsten. Imagine a composite material, like carbon fiber, but made entirely of metal. This "woven" tungsten is tougher and more resistant to cracking.

Breeding the Fuel

Fusion uses Deuterium (abundant in water) and Tritium (incredibly rare). A commercial plant must make its own Tritium. This is done in the Breeding Blanket, a layer of lithium surrounding the reactor core.

- The Alchemy: When a fusion neutron hits a lithium atom in the blanket, it splits it into Helium and Tritium. This Tritium is then harvested and pumped back into the core.

- Current Status: Companies like Kyoto Fusioneering are building "UNITY," a test loop to circulate liquid lithium-lead alloys at 1,000°C. They are testing advanced ceramic composite materials (SiC/SiC) that can survive this corrosive, hot, radioactive environment.

Part VI: The Future Outlook

As we look toward the latter half of the 2020s, the fusion industry is entering a "valley of death" and "peak of hope" simultaneously.

- The Engineering Reality Check: The physics is largely proven. The challenge now is supply chain. Can we manufacture thousands of kilometers of HTS tape? Can we 3D-print stellarator coils with micron-level precision? Can we breed enough Tritium to start the first generation of reactors?

- The Geo-Political Angle: Fusion is becoming a national security asset. The UK, US, China, and Japan are all vying for leadership. China’s EAST reactor is setting duration records, while the US is leveraging its private sector dynamism.

- The Energy Mix: If successful, fusion will not just replace coal; it will complement renewables. Solar and wind are intermittent; fusion is baseload. It is the "always-on" clean energy that data centers, AI factories, and heavy industry are desperate for.

Conclusion

We are no longer just staring at the stars, wondering how they work. We are building them. The transition from "experiment" to "industry" is messy, expensive, and fraught with delays, but it is happening. With AI acting as the brain, HTS magnets as the muscles, and advanced composites as the bones, the fusion machines of 2025 are the most complex objects ever engineered by humanity.

Taming the sun is no longer a question of if, but when. And for the first time in history, when looks like it might be within our lifetimes.

Reference:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OCCUSgNX5s0

- https://www.fabbaloo.com/news/3d-printing-revives-fusion-energy-dreams-princetons-stellerator-prototype-on-a-budget

- https://www.voxelmatters.com/pppl-builds-its-first-stellarator-in-decades-using-3d-printing/

- https://www.cryogenicsociety.org/index.php?option=com_dailyplanetblog&view=entry&year=2024&month=09&day=11&id=369:tests-show-high-temperature-superconducting-magnets-ready-for-fusion

- https://www.helionenergy.com/technology/

- https://arpa-e.energy.gov/programs-and-initiatives/search-all-projects/compression-frc-targets-fusion

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HlNfP3iywvI

- https://www.helionenergy.com/articles/more-on-helions-pulsed-approach-to-fusion/

- https://cfs.energy/technology/hts-magnets/

- https://www.iter.org/machine/supporting-systems/tritium-breeding

- https://atap.lbl.gov/research/scientific-programs-and-centers/superconducting-magnet-program/superconducting-magnets-for-fusion-energy/

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-plasma-physics/article/breeder-blanket-and-tritium-fuel-cycle-feasibility-of-the-infinity-two-fusion-pilot-plant/248C49CCA0B7ABEA2F7BF7031290EDC4