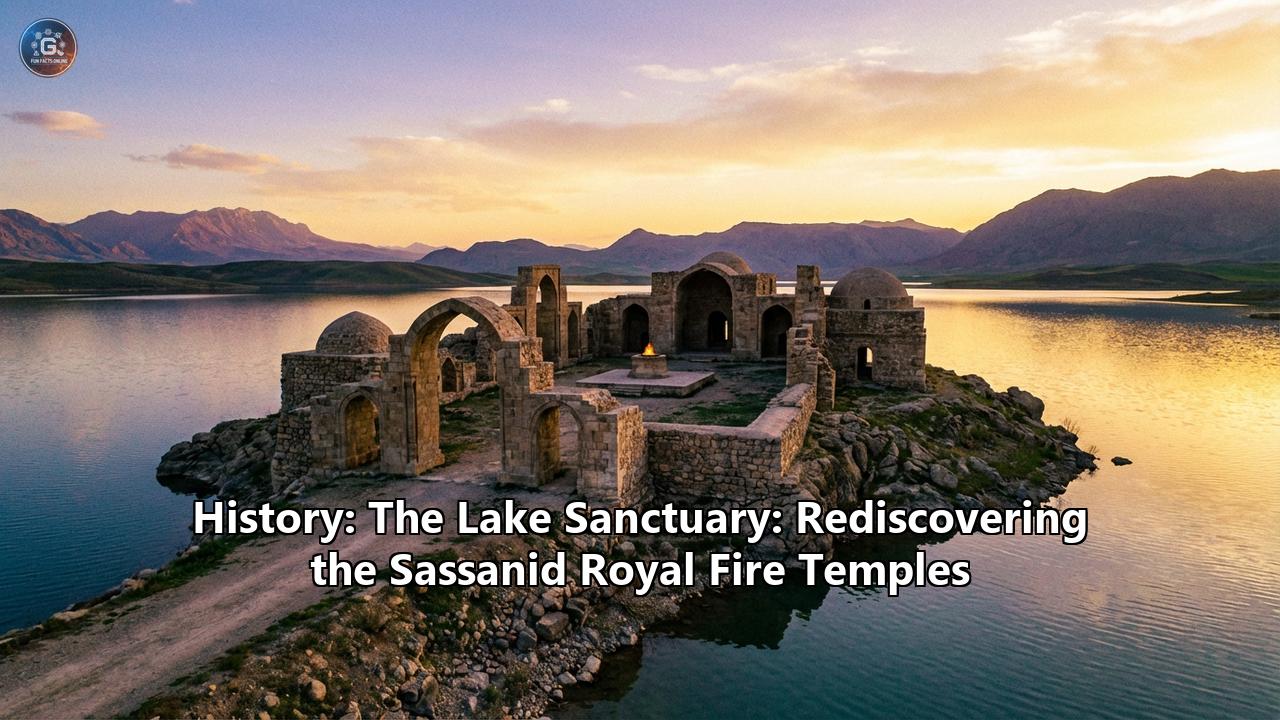

In the remote, wind-swept highlands of northwestern Iran, a geological miracle rises from the earth. It is a flat-topped mesa, a platform of stone that seems to float above the surrounding valley, crowned not by a jagged peak, but by a serene, azure eye—a bottomless lake that has stared up at the sky for millennia. To the casual observer, these ruins might look like the bleached bones of a forgotten fortress, silent and imposing against the backdrop of the Zagros Mountains. But to the historian, the archaeologist, and the seeker of ancient mysteries, this place is Takht-e Soleyman, the "Throne of Solomon."

For centuries, local legends whispered that this was the work of the Biblical King Solomon, who commanded jinn and demons to build a massive citadel and imprisoned rebellious monsters in the hollow volcano nearby. But beneath these layers of myth lies a truth even more spectacular. This was Shiz, the spiritual heart of the Sassanid Empire. It was the home of Adur Gushnasp, the "Fire of the Stallion," one of the three Great Royal Fires of Zoroastrianism. For over four hundred years, this sanctuary was the Vatican of the ancient Persian world, a place where emperors walked barefoot to receive their divine right to rule, where water and fire danced in a sacred union, and where the fate of empires was decided.

This is the story of that sanctuary—its mythological origins, its architectural grandeur, its tragic fall, and its miraculous rediscovery by modern archaeology.

Part I: The Sacred Landscape

The Miracle of the Lake

To understand why kings and priests chose this remote location for their holiest shrine, one must first understand the geology of the site. Takht-e Soleyman is not a man-made hill; it is a creation of the earth itself. The entire platform, rising some 60 meters above the surrounding plain, is a massive deposit of travertine limestone formed by the overflow of the artesian lake at its center.

For thousands of years, water rich in calcium and minerals has bubbled up from the depths of the earth. As the water reached the surface and evaporated, it left behind microscopic layers of stone. Century by century, these layers built up, creating a natural pedestal that grew higher and wider, lifting the lake toward the heavens. The lake itself is an enigma. Roughly 80 by 120 meters in size, its water remains a constant 21°C (70°F) year-round, unaffected by the freezing winters or scorching summers of the Iranian plateau. It is incredibly deep—plunging down over 100 meters into a funnel-shaped vent that connects directly to the aquifer below.

To the ancient mind, this was not geology; it was divinity. In Zoroastrian cosmology, water (Aban) and fire (Atar) are the two agents of ritual purity. To find a site where a ceaseless, life-giving spring existed atop a mountain was already a sign of favor. But the region was also volcanically active. Vents in the earth released gases that could be lit, creating "eternal fires." The combination of the two—the unfathomable water and the unquenchable fire—created a "hierogamy," a sacred marriage of elements that made Shiz the most holy place on earth.

The Prison of Solomon

Dominating the horizon three kilometers west of the sanctuary is a terrifying geological twin: a hollow, cone-shaped mountain known as Zendan-e Soleyman ("Solomon’s Prison"). Rising 100 meters into the air, this phantom volcano is the fossilized remains of an older spring. Once, it too was a lake atop a hill. But as its mineral deposits built the walls higher and higher, the pressure eventually cut off the water flow. The water drained away, leaving a gaping, empty crater 80 meters deep.

Local folklore claimed that King Solomon used this terrifying pit as a dungeon for disobedience djinns (demons). Looking into the abyss of the Zendan, with its sheer rock walls plunging into darkness, it is easy to see why such legends were born. In reality, the Zendan was a site of worship long before the Sassanids. Archaeologists have found shrines dating back to the 1st millennium BCE clustered around the rim of the crater, proving that this landscape has been revered as sacred for nearly 3,000 years.

Part II: The Rise of the Fire Keepers

The Sassanid Renaissance

The story of Adur Gushnasp's golden age begins with the rise of the Sassanid Empire in 224 CE. After centuries of Greek influence under the Seleucids and the loose, feudal federation of the Parthians, the Sassanids burst onto the scene with a mission of national and religious restoration. They viewed themselves as the true heirs of the ancient Achaemenids (Cyrus and Darius), and their ideology was fiercely Zoroastrian.

Under the Sassanids, Zoroastrianism became the state religion. It was organized, codified, and integrated into the government machinery. At the top of this religious hierarchy were the three "Great Fires" (Atash Behram), each associated with a specific class of society:

- Adur Farnbag: The Fire of the Priests (Athravan), located in Pars.

- Adur Burzen-Mihr: The Fire of the Farmers (Vastryosh), located in Parthia.

- Adur Gushnasp: The Fire of the Warriors (Arteshtar), located here, in Media (Azerbaijan).

Because the Sassanid kings were the ultimate warriors and commanders-in-chief, Adur Gushnasp became the Royal Fire. It was the personal fire of the monarchy. The Sassanids invested heavily in the site, transforming a modest local shrine into a monumental complex that rivaled the palaces of Ctesiphon.

The Legend of the Stallion

The name Adur Gushnasp means "Fire of the Stallion" (from the Middle Persian gushn meaning male and asp meaning horse). The mythology behind this name is preserved in the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) and older Pahlavi texts.

The legend tells of the mythical King Kay Khosrow, a paragon of justice and piety. While waging a holy war against the sorcerer-king Afrasiyab to capture the demon-fortress of Bahman, Kay Khosrow found his armies enveloped in magical darkness. He prayed to Ahura Mazda for guidance. Suddenly, a divine fire descended from the heavens and settled on the mane of his horse. The fire burned brightly but did not consume the horse or harm the king. It illuminated the battlefield, dispelling the magical darkness and allowing Kay Khosrow to destroy the idol-temple and conquer the fortress.

In gratitude, Kay Khosrow established a fire temple on the summit of Mount Asnavand (identified with Takht-e Soleyman) and enshrined the divine fire there. This myth linked the Sassanid dynasty directly to the Kayanian kings of old, weaving their political legitimacy into the fabric of cosmic history. Every time a Sassanid king paid homage to Adur Gushnasp, he was stepping into the shoes of Kay Khosrow, the ideal monarch.

Part III: The Architecture of Holiness

Thanks to the extensive excavations by the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) led by Rudolf Naumann and Dietrich Huff in the 1960s and 70s, we have a remarkably clear picture of what the complex looked like at its zenith in the 6th century CE, under the reign of Khosrow I (Anushirvan).

The Fortifications

The sanctuary was designed to be impregnable, both physically and spiritually. A massive oval wall, 13 meters high and 3 meters thick, encircled the entire lake platform. Constructed of rough-hewn stone faced with dressed masonry, the wall was punctuated by 38 semicircular bastions. Two monumental gates granted access: the Northern Gate, which was the main ceremonial entrance, and the Southern Gate.

The Fire Precinct

Upon entering the Northern Gate, a pilgrim would be funneled through a long, walled processional way that blocked the view of the lake, creating a sense of suspense. This path led into a large courtyard, finally revealing the sanctuary complex.

The heart of the temple was the Chahartaq ("Four Arches"). This was the standard form of Sassanid religious architecture: a square chamber with four large arched openings, surmounted by a dome.

- The Central Sanctuary: The main Chahartaq at Takht-e Soleyman was massive, built of fired brick. This was the holy of holies. Beneath the dome stood the supreme Fire Altar. The fire burned in a large metal vessel, likely silver or gold, placed atop a three-stepped stone pedestal.

- The Ritual: The fire was kept perpetually burning by priests who fed it with dry, clean wood (often sandalwood) and purified animal fat. They wore mouth veils (padam) to prevent their breath from polluting the sacred flame.

- The Hidden Corridors: Surrounding the central domed chamber were narrow, vaulted corridors. These were likely used for ritual circumambulation and for the priests to move unseen, maintaining the "mystery" of the fire for the lay worshippers observing from the outer halls.

The Temple of Anahita

Adjacent to the fire temple was a second, equally important structure: the Temple of Anahita. While the fire temple was a closed, domed space representing heat and light, the water temple was likely an open-air courtyard or hall featuring channels of flowing water.

Archaeologists found a sophisticated system of stone channels and basins that diverted water from the overflowing lake, running it through the temple precincts before cascading it down the side of the hill to irrigate the surrounding lands. This architectural integration of the lake's water into the temple structure reinforced the theological bond between Fire (the King) and Water (the Goddess/Queen).

The Treasury

Adur Gushnasp was unimaginably wealthy. Sassanid kings showered the temple with gifts. According to historical records, Bahram V (Bahram Gur) donated the jewels of the Khatun (queen) of the Turks, whom he had defeated in battle. Khosrow I donated vast sums of gold and booty from his campaigns against the Romans (Byzantines). Khosrow II (Parviz) vowed that if he defeated the usurper Bahram Chobin, he would give the temple golden ornaments. He kept his promise, sending a gold cross (looted from Jerusalem) and other treasures.

The temple treasury would have been filled with gold vessels, silk carpets, jeweled swords, and tens of thousands of silver drachms. It served as a national reserve bank, its sanctity protecting the state's wealth.

Part IV: The Royal Pilgrimage

The relationship between the King and the Fire was the central pillar of Sassanid statecraft. The coronation ceremony itself did not happen at Takht-e Soleyman—that usually took place in the capital, Ctesiphon. However, immediately after the coronation, it was customary for the new King of Kings (Shahanshah) to undertake a pilgrimage to Adur Gushnasp.

This was not a leisurely trip. The King would travel north from Ctesiphon (near modern Baghdad), crossing the Zagros Mountains. When the royal caravan reached the foot of the massive limestone hill, the King would dismount. To show his humility before the divine fire, he would walk the final ascent on foot.

Imagine the scene: The Emperor of the Persians, the ruler of the known world, climbing the dusty path in his jeweled robes. At the top, he would pass through the massive gates and kneel before the Fire. He would seek oracles from the High Mobad (Priest), offer sacrifices, and pray for victory and a long reign.

The fire was also a consultant in war. Before major campaigns against the Hephthalites in the East or the Romans in the West, the King would visit Adur Gushnasp. If the fire burned brightly and clearly, it was an omen of victory. If it smoked or guttered, it was a warning. The "Warrior Fire" was essentially the spiritual general of the Sassanid army.

Part V: The Fall of the Sanctuary

The glory of Adur Gushnasp came to a violent end in the 7th century, a casualty of the titanic struggle between the Persian and Byzantine Empires.

In the early 7th century, Khosrow II had pushed the Persian Empire to its greatest extent, capturing Jerusalem, Egypt, and threatening Constantinople itself. In a desperate counter-attack, the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius launched a daring campaign deep into Persian territory in 624 CE.

Heraclius knew that Adur Gushnasp was the spiritual heart of the enemy. Striking at it would be a psychological blow equal to the destruction of an army. Bypassing the Persian armies, he marched his troops through the mountains of Armenia and descended upon Ganzak (the city near the temple).

The Persian garrison fled. Heraclius entered the sacred precinct. For a Christian emperor, this was the lair of "fire-worshipers." He ordered the fire altars overturned, the golden vessels looted, and the buildings put to the torch. The great fire, which had burned for centuries, was extinguished. The waters of the sacred lake were polluted with the corpses of the defenders.

Though the Sassanids briefly retook the site and may have rekindled the fire, the empire was fatally wounded. Just a few decades later, the Arab Muslim armies swept across the plateau. The Sassanid Empire collapsed in 651 CE.

The Survival Strategy: The Throne of Solomon

With the arrival of Islam, Zoroastrian fire temples were systematically destroyed or converted into mosques. Adur Gushnasp faced annihilation. However, the local population—or perhaps the remaining priests—devised a brilliant survival strategy.

They knew that the Quran revered King Solomon (Suleiman) and recognized him as a prophet. The massive stone walls, the bottomless lake, and the "prison" mountain were so impressive that it was easy to claim they were built by Solomon's supernatural command. By renaming the site Takht-e Soleyman (The Throne of Solomon) and the volcano Zendan-e Soleyman (The Prison of Solomon), they wrapped the Zoroastrian sanctuary in a cloak of Islamic legitimacy.

This ruse worked. While the fire was eventually extinguished and the priests dispersed, the stones were not torn down. The site was respected as a place of Solomon's power.

Part VI: The Mongol Summer Palace

For centuries, the site lay mostly dormant, inhabited by local farmers and shepherds. But in the 13th century, it experienced a second golden age. The Ilkhanid dynasty, the Mongol rulers of Iran, fell in love with the site.

The Mongols were originally nomadic steppe people. They disliked the heat and confinement of cities like Tabriz or Baghdad. They preferred high, cool pastures where they could hunt and camp. The high plateau of Takht-e Soleyman, with its abundant water and lush grass, was perfect.

Abaqa Khan (r. 1265–1282), the son of Hulagu Khan, chose the ruins of the fire temple as the site for his summer palace. He did not bulldoze the Sassanid ruins; he built on top of them and around them, respecting the ancient layout.- The Courtyard: The Sassanid processional path became a grand courtyard.

- The Iwans: The Sassanid arches were repaired and redecorated.

- The Tiles: This is where the Ilkhanids left their most distinct mark. They covered the walls with magnificent Lajvardina tiles (cobalt blue and gold). These tiles were masterpieces of ceramic art, featuring Chinese-inspired motifs like dragons and phoenixes (simorghs), interwoven with verses from the Shahnameh.

It is a poetic irony: The Mongol Khans, who were Buddhist or Christian before converting to Islam, decorated their palace with verses from the Persian Book of Kings, celebrating the very Sassanid monarchs whose ruins they were inhabiting. They saw themselves as the new "Rostam" or "Kay Khosrow," adopting Persian kingship traditions to legitimize their alien rule.

Part VII: The Rediscovery

By the 16th century, the Ilkhanid palace was abandoned. The site crumbled into a romantic ruin, visited only by nomads. The name "Adur Gushnasp" was forgotten, surviving only in obscure Pahlavi manuscripts. To the world, it was just the Throne of Solomon.

The European Travelers

In the 19th century, the Great Game brought European diplomats, spies, and explorers to Persia. In 1819, the British traveler and artist Sir Robert Ker Porter visited the site. He was awestruck by the "bottomless" lake and the cyclopean walls. He sketched the ruins, bringing the first visual record of Takht-e Soleyman to the West.

Later, in 1838, Sir Henry Rawlinson (the man who deciphered the Behistun inscription) visited. He was the first to tentatively suggest that this "Throne of Solomon" might actually be the lost city of Shiz and the site of the famous fire temple.

The Excavations

The true identity of the site was confirmed in the 20th century. In 1937, the American surveyors Arthur Upham Pope and Donald Wilber photographed the site from the air, revealing the mesmerizing oval geometry of the citadel.

But the real work began in 1959, when the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) launched a massive excavation project. Led by Rudolf Naumann and later Dietrich Huff, and joined by Swedish and Iranian teams, they dug for nearly two decades.

The excavation was difficult. The Ilkhanid palace had been built directly on top of the Sassanid temple, meaning archaeologists had to carefully peel back one layer of history to see the other, without destroying either.

The "Aha!" Moment:The definitive proof that this was indeed Adur Gushnasp came with the discovery of a cache of clay bullae. These were small clay seal impressions used to secure documents and goods. On them, in Sassanid Pahlavi script, was the title:

"The High Priest of the House of the Fire of Gushnasp" (Mowbed i xanag i Adur i Gushnasp).With this find, the mist of legend evaporated. The Throne of Solomon was reclaimed by history. It was the Fire of the Stallion.

Part VIII: The Sanctuary Today

In 2003, UNESCO recognized Takht-e Soleyman as a World Heritage Site. Today, it is one of the most atmospheric and evocative sites in the Middle East.

Visitors who make the long journey from Zanjan or Tabriz find a place of profound silence. The wind whistles through the broken arches of the Chahartaq. The water of the lake is still a piercing, unnatural blue, calm as a mirror. You can walk along the edge of the water, looking down into the depths where Sassanid priests once poured offerings of silver coins.

The Ilkhanid tiles are mostly gone, moved to museums in Tehran and Berlin, but fragments of the blue glaze still glitter in the dust. The massive Sassanid brickwork still stands, a testament to the engineering genius of the ancients.

Walking out to the Western Iwan, you can look toward the jagged silhouette of the Zendan-e Soleyman. It stands as a dark sentinel, a reminder of the deep time that governs this landscape.

The Enduring Legacy

Takht-e Soleyman is more than just a ruin. It is a testament to the continuity of Iranian culture.

- It shows the transition from Nature Worship (the lake and volcano) to Institutional Religion (the Sassanid Fire Temple).

- It shows the survival of Persian identity through the Arab Conquest, masked by the name of Solomon.

- It shows the assimilation of invaders, as the Mongols became patrons of Persian art and mythology, building their palace on the foundations of the kings they sought to emulate.

The fire of Adur Gushnasp may have been extinguished 1,400 years ago, but the spirit of the place remains. The water still flows, the wind still blows, and the stones still whisper the stories of the Warrior Kings who once knelt here, hoping to hold the favor of the heavens.

In the end, the Lake Sanctuary teaches us that while empires fall and fires die out, the sacred geography of the earth itself remembers.

Reference:

- https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/adur-gusnasp-an-atas-bahram-see-atas-that-is-a-zoroastrian-sacred-fire-of-the-highest-grade-held-to-be-one-of/

- https://www.tasteiran.net/stories/28/takht-e-soleyman

- https://grokipedia.com/page/Adur_Gushnasp

- https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/520504/Takht-e-Soleyman-A-3-000-year-old-mystery-in-Iran-s-history

- https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/1077.pdf

- https://whc.unesco.org/document/151679

- https://welcometoiran.com/takht-e-soleyman/

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1077/

- https://arasbaran.org/en/news.cfm?id=18

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adur_Gushnasp

- https://caravanistan.com/trip-reports/takht-e-soleyman/

- https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/takt-e-solayman/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kay_Khosrow

- https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/coronation-pers/

- https://gateofalamut.com/en/takht-e-soleyman-iran/

- https://zoroastrians.net/2022/07/30/in-takht-e-soleyman-where-inner-peace-meets-outer-beauty/