An Unfrozen Saga: How Melting Ice Is Revealing a 1,500-Year-Old Reindeer Hunting Megastructure in Norway

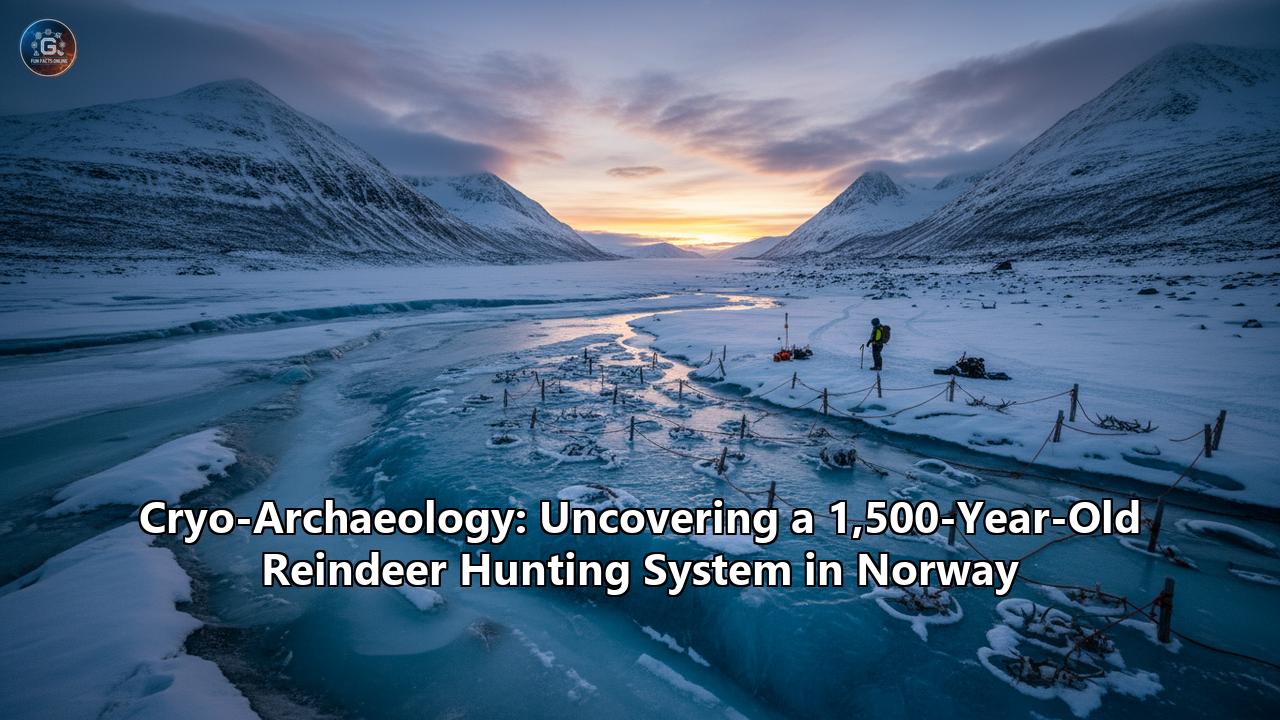

High in the remote, windswept mountains of Norway, a story frozen in time is rapidly coming to light. As ancient ice beats a hasty retreat under the pressures of a warming climate, it is surrendering the secrets of a lost world. In an extraordinary revelation, archaeologists are uncovering a massive and remarkably well-preserved reindeer hunting system, an intricate network of wood and stone that has lain dormant for 1,500 years. This discovery, emerging from the ice on the Aurlandsfjellet mountain plateau in Vestland County, is not just a collection of static artifacts; it is a dynamic window into the lives, ingenuity, and social organization of Iron Age people who thrived in this harsh, unforgiving landscape. It speaks of a time when vast herds of reindeer were the lifeblood of mountain communities, and their capture was a sophisticated, large-scale enterprise that shaped both the economy and the very fabric of society.

This is the domain of cryo-archaeology, or glacier archaeology, a field of study that races against time. With each passing summer, more of our planet's frozen heritage is exposed, offering an unprecedented opportunity to recover organic artifacts—wood, leather, textiles, and bone—that would have long since vanished in other environments. Yet, this is a fleeting gift. The same elemental forces that reveal these treasures also threaten to destroy them. The story of the Aurlandsfjellet hunting system is therefore one of both discovery and urgency, a compelling narrative of ancient innovation and modern-day preservation.

A Whisper from the Ice: The Discovery on Aurlandsfjellet

The first hint of this monumental discovery was not made by a team of archaeologists in a planned excavation, but by a local hiker with a keen eye and a deep appreciation for the history of his homeland. Helge Titland, who has a passion for documenting ancient hunting sites in the region, was trekking across the Aurlandsfjellet plateau in 2024 when he noticed unusual pieces of carved wood emerging from the edge of a melting ice patch. Recognizing that these were not naturally fallen branches, he reported his findings, setting in motion a chain of events that would lead to one of the most significant archaeological discoveries in Norway in 2025.

Archaeologists from the Vestland County Council and the University Museum of Bergen were alerted and added the location to their growing list of high-priority sites to investigate. When they returned to the site with Titland the following autumn, the scene had been transformed. More of the ice had melted, revealing the true and staggering scale of what lay beneath. What Titland had initially glimpsed were not just a few scattered logs, but components of a vast, man-made structure.

As the archaeologists began their meticulous work in the challenging high-altitude environment, the full extent of the hunting system started to emerge. Hundreds of wooden logs, many of them meticulously carved and shaped, were found, forming an elaborate mass-hunting installation. This was not a simple trap, but a highly organized and engineered system designed for the mass capture of reindeer. The discovery was hailed as unique, not only in Norway but possibly in all of Europe, as it was the first time such a large-scale wooden trapping structure had been found melting out of the ice.

Engineering an Arctic Harvest: The Anatomy of a 1,500-Year-Old Trap

The genius of the Aurlandsfjellet hunting system lies in its sophisticated understanding of reindeer behavior and its ambitious scale. The best-preserved part of the installation consists of two long, converging fences made of wooden posts and branches, which would have created a funnel-like effect, guiding the reindeer towards a deadly destination. This was a psychological as well as a physical barrier. Reindeer are known to be shy of unfamiliar, man-made structures and moving objects, a behavior that ancient hunters exploited with deadly efficiency. At other sites in Norway, archaeologists have found "scaring sticks," which were placed in lines to spook the animals and direct their movements. While not explicitly mentioned in the initial finds at Aurlandsfjellet, the principle of using fences to manipulate the herd's path is the same.

The converging fences led to a large enclosure or pen, constructed from heavy timber, where the reindeer were ultimately herded and killed. This design demonstrates that this was not opportunistic hunting by a few individuals, but a systematic and organized mass capture operation. Leif Inge Åstveit, an archaeologist at the University Museum of Bergen, emphasized the systematic nature of the hunt, stating, "We see that there has been mass capture. This was not random hunting. The animals were led into the pen, captured and killed systematically.”

The sheer scale and complexity of the structure indicate a significant investment of labor and resources by the community that built it. These were permanent hunting installations, meticulously planned and constructed to be used repeatedly. The choice of location was also critical, situated in a landscape that was prime reindeer territory. The builders of this system possessed an intimate knowledge of the local topography and the migratory routes of the reindeer herds.

A Frozen Time Capsule: The Artifacts of the Hunt

The exceptional preservation conditions of the ice have yielded a treasure trove of artifacts that provide a vivid picture of the hunting activities that took place on Aurlandsfjellet 1,500 years ago. These are not just the tools of the hunt, but also personal items that connect us directly to the people who once walked these mountains.

Evidence of the Kill:A crucial piece of evidence confirming the purpose of the site is a large cache of reindeer antlers found near the trapping structure. Many of these antlers bear deep and distinctive cut marks, providing clear proof that the animals were not only killed but also processed on-site. Archaeologist Øystein Skår of Vestland County Council noted, "All antlers have markings, which gives us deeper insight into the hunting activity itself." These markings reveal the systematic butchering of the reindeer, a clear sign of organized, large-scale animal processing. Zooarchaeological analysis of such remains can reveal a wealth of information, including the age and sex of the animals targeted, which in turn provides insights into hunting strategies and herd management.

In addition to the antlers, archaeologists have recovered a formidable arsenal of hunting weapons. These include numerous iron spearheads, wooden spear shafts, arrow shafts, and even fragments of bows. The presence of these weapons leaves no doubt about how the trapped reindeer met their end. Some of the arrowheads found at similar sites in Norway are so well-preserved that they still have the sinew lashings and pitch used to attach them to the wooden shaft.

Personal Touches and Mysterious Objects:Beyond the tools of the trade, the melting ice has also revealed more personal and enigmatic items. One of the most remarkable finds is a beautifully crafted dress pin made of antler, shaped like a miniature axe. This delicate brooch was likely a personal adornment worn by one of the hunters and was probably lost during the intense activity of the hunt. It is an exceptionally rare find that offers a tangible connection to an individual from the past.

Perhaps the most intriguing and mysterious discoveries are several decorated wooden paddles or oars. These objects seem entirely out of place at a high-altitude hunting site, far from any significant body of water. Their purpose is currently unknown and has sparked considerable debate among archaeologists. The paddles are finely carved with delicate ornamentation, suggesting they were objects of some importance. Their presence raises new questions about the activities that took place at these hunting sites. Were they brought here for a specific, unknown purpose related to the hunt? Or do they hint at some form of ritual or symbolic practice that we are only beginning to comprehend?

Some scholars have noted that in other prehistoric contexts, decorated paddles and oars have been associated with ritualistic activities, sometimes shaped to represent animals or other symbolic forms. It is possible that these paddles had a ceremonial function, perhaps related to the spiritual aspects of the hunt, which was a critical and often dangerous undertaking. Further research on these unique artifacts is needed to unravel their secrets.

The diversity of the artifacts, from heavy-duty hunting gear to finely crafted personal items and mysterious paddles, suggests that these hunting expeditions were well-equipped and likely involved a temporary settlement at the site.

A World Plunged into Cold: The Late Antique Little Ice Age

The remarkable preservation of the Aurlandsfjellet hunting system is a direct consequence of a dramatic and prolonged period of climate change known as the Late Antique Little Ice Age (LALIA). This period of global cooling, which lasted from roughly 536 to 660 AD, was likely triggered by a series of massive volcanic eruptions that spewed vast amounts of sunlight-blocking particles into the atmosphere. The result was a "volcanic winter" that led to crop failures, famine, and significant societal upheaval across the Northern Hemisphere.

The Aurlandsfjellet hunting system dates to the mid-sixth century CE, precisely at the onset of this cold period. It is believed that the increasingly cold temperatures and growing ice and snow cover rendered the trapping system unusable, leading to its abandonment. The constant snow accumulation then sealed the entire structure under a protective blanket of ice before the wood, antler, and metal could decay. For over a millennium, these artifacts remained in a natural, deep-frozen state, a time capsule waiting to be opened.

Interestingly, while one might expect such a harsh climatic period to lead to a decrease in human activity in the mountains, archaeological evidence from other sites in Norway suggests the opposite may be true. Researchers analyzing a large number of radiocarbon-dated artifacts from the glaciers of Oppland County were surprised to find a possible increase in mountain hunting activity during the LALIA. Dr. James H. Barrett, an environmental archaeologist from the University of Cambridge, suggests that the importance of mountain hunting, particularly for reindeer, may have increased to supplement failing agricultural harvests in the lowlands. This highlights the resilience and adaptability of Iron Age communities, who turned to the mountains for survival when their traditional food sources were threatened.

The Science of the Ice: Reading the Clues

The recovery of these frozen artifacts is just the first step in a long and complex process of scientific analysis. A range of advanced techniques is being employed to extract as much information as possible from these invaluable finds.

Dating the Past:The primary method for determining the age of organic artifacts like wood, antler, and leather is radiocarbon dating. This technique measures the decay of the radioactive isotope carbon-14 to establish when the organism died. By radiocarbon dating the various components of the hunting system and associated artifacts, archaeologists can build a precise timeline of when the site was constructed, used, and abandoned.

For wooden artifacts, another powerful tool is dendrochronology, or tree-ring dating. By analyzing the patterns of tree rings in the preserved logs, scientists can potentially date the felling of the trees with great precision. This can also provide valuable information about the climate and environmental conditions at the time the trees were growing.

Analyzing the Materials:The artifacts themselves are subjected to a battery of scientific analyses. The wood from the hunting structure and other artifacts can be identified to determine the species of trees used, which in turn sheds light on the past forest composition and the choices made by the ancient builders. The iron spearheads are analyzed to understand the metallurgy of the period, including the techniques used to smelt and forge the iron.

The reindeer antlers and bones are a particularly rich source of information. Zooarchaeological analysis can determine the age, sex, and condition of the animals, revealing hunting patterns and the health of the herd. Isotope analysis of the bones and antlers can provide insights into the reindeer's diet and migratory patterns. Furthermore, ancient DNA (aDNA) can be extracted from the remains to study the genetic history of the reindeer population.

Cryo-Archaeology: A Race Against Time

The discovery at Aurlandsfjellet is a powerful testament to the potential of cryo-archaeology. The "Secrets of the Ice" program, a collaboration between the Innlandet County Council and the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo, has been at the forefront of this research, recovering thousands of artifacts from Norway's melting glaciers since 2011. These finds range from Stone Age arrows to Viking-era clothing, skis, and horse equipment, and they are fundamentally changing our understanding of how ancient people used the high mountains.

The finds have shown that the mountains were not desolate, empty spaces in the past, but were intensively used and connected to the wider world through trade and travel. However, this burgeoning field of archaeology is defined by its urgency. The same climate change that is revealing these sites is also their greatest threat. Once exposed from their icy tombs, the fragile organic artifacts begin to deteriorate rapidly when subjected to the elements.

The archaeologists of the "Secrets of the Ice" program and other similar initiatives are in a constant race against time to survey the melting ice patches, recover the artifacts, and ensure their preservation. All the materials recovered from Aurlandsfjellet are now being carefully stabilized at the conservation department of the University Museum in Bergen. The waterlogged wood must be dried out slowly and carefully to prevent it from warping and cracking, while the iron artifacts undergo treatment to prevent corrosion. The mountain area itself has been placed under protection by Norway's Cultural Heritage Act to prevent looting and damage.

A Legacy in Wood and Ice

The 1,500-year-old reindeer hunting system emerging from the ice on Aurlandsfjellet is more than just an archaeological curiosity. It is a profound testament to the ingenuity, organizational capacity, and resilience of the people who lived in Iron Age Norway. It provides a rare and detailed glimpse into a sophisticated, large-scale hunting economy that was vital to the prosperity of mountain communities.

This discovery underscores the deep and intimate knowledge these ancient hunters had of their environment and the animals they depended on. It speaks of a society capable of organizing large groups of people for communal tasks, from the construction of massive trapping systems to the systematic processing of the captured animals.

As the ice continues to melt, it is certain that more secrets will be revealed. Each new artifact, from a humble wooden peg to an enigmatic decorated paddle, adds another piece to the complex puzzle of our past. The work of cryo-archaeologists is not only about salvaging these treasures but also about listening to the stories they have to tell—stories of survival, innovation, and a way of life intricately woven into the majestic and unforgiving landscapes of the north. The unfreezing of this ancient saga is a poignant reminder that the past is not gone; it is merely waiting, preserved in the ice, for us to find it.

Reference:

- https://www.sciencenorway.no/archaeology-forskningno-norway/discoveries-from-1400-year-old-ice-surprise-scientists/1453698

- https://indiandefencereview.com/melting-glaciers-norway-viking-treasures/

- https://lamont.columbia.edu/news/melting-glaciers-reveal-clues-climate-adaptation-norways-mountains

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/2000-artifacts-pulled-edge-norways-melting-glaciers-180967949/

- https://archaeologymag.com/2025/08/melting-ice-reveals-viking-age-packhorse-net/

- https://www.sciencenorway.no/archaeology-climate-change-glaciers/ancient-remains-from-reindeer-hunting-and-a-forgotten-trail-in-the-norwegian-mountains-found-by-glacial-archaeologists/1984859

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392491902_Reindeer_archaeology_in_northern_Norway_A_research_excavation_report_from_Gollevarre_and_Drag

- https://septentrio.uit.no/index.php/tromura/article/view/8101

- https://www.livescience.com/archaeology/archaeologists-discover-1-500-year-old-reindeer-trap-and-other-artifacts-melting-out-of-the-ice-in-norways-mountains

- https://www.ancient-origins.net/

- https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/frozen-in-time-glacial-archaeology-on-the-roof-of-norway

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Late_Antique_Little_Ice_Age

- https://courier.unesco.org/en/articles/melting-ice-reveals-past

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5792946/

- https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2025/04/04/melting-glaciers-reveal-clues-to-climate-adaptation-in-norways-mountains/

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/travel/news/frozen-for-centuries-bizarre-artifacts-emerge-from-norways-melting-glaciers/articleshow/118625914.cms